|

THE CAMP JACKSON AFFAIR

Activities in St. Louis soon threw the state into further frenzy.

Frank Blair returned to St. Louis on the day of Jackson's rejection of

Lincoln's call, armed with a War Department authorization of five

thousand stand of arms to those Home Guard units who would enlist in the

federal army. With an enlistment agent in the city (Lieutenant John M.

Schofield, a West Pointer on leave in the city with orders to act as

mustering officer in Missouri and whose presence Jackson had ignored),

Blair and Lyon by week's end had mustered and armed more than

twenty-five hundred recruits, most of them Germans, at the St. Louis

Arsenal, with authorization for as many as ten thousand. The action was

unconstitutional; Congress alone had authority to create federal

volunteers, who were neither state militia nor members of the U.S. Army.

As many Missourians saw the matter, such enlistment only implicated

government officials from Lyon and Blair to Lincoln in a vast conspiracy

against the states. Moreover, the St. Louis military leaders had

managed to secrete virtually the entire cache of arms and munitions from

the arsenal across the river to Illinois, thus thwarting any repeat of

the Liberty Arsenal predation and eliminating any threat of attack in

St. Louis.

|

AN AUGUST 1861 ENGRAVING OF THE ARSENAL AT ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

As if scripted, Missouri's world turned upside down within four days

of the militia's encamping. On May 10, during the temporary absence of

the federal commander in St. Louis, William S. Harney, Lyon and Blair

marched some 6,500 troops from the St. Louis Arsenal to Camp Jackson, a

militia encampment on the western edge of St Louis, forcing the

surrender of those 669 militia (of 891 in camp) who had not managed to

escape the converging federal columns. Reports reached Lyon that the

Confederate cannon from Baton Rouge, poorly disguised in boxes marked as

marble, had arrived at night by steamer and that they, along with those

cannon held by the state and shipped "for repairs" to the encampment's

commander, Daniel M. Frost, were secreted to the camp. The federal

commander also had learned that Jefferson City was awash in troops,

powder, and arms—including the cannon taken from the Liberty

Arsenal—and he ordered a preemptive strike, reasoning dubiously

that the camp was a threat to the arsenal. Many of the militia were

clearly secessionist, naming their company streets "Beauregard" and

"Davis" for the Confederate general and president and displaying

secession flags; one even wrote the night before the incident to his

brother in Natchez, Mississippi, on Confederate stationery, a letter

that was never delivered for federal troops captured it the next day,

that "we shall conquer for the Southern Confederacy and Jef Davis

Dam Lincoln and the Stars and Stripes, we are for the south."

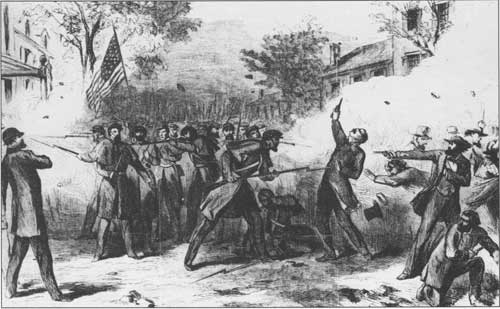

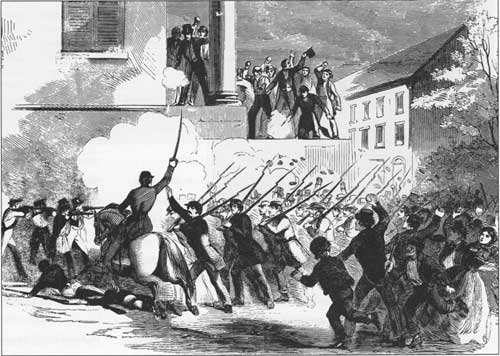

After capturing the militia, in a grandiose display of might Lyon

marched the prisoners under guard, through hostile throngs that now

packed the city streets, for nearly the entire six miles from the camp

to the arsenal. The humiliating procession soon erupted in violence; in

response to a small fracas near the center of the column, the barely

trained Home Guard units opened fire on the crowd, resulting in

twenty-eight deaths and as many as seventy-five injuries. For the next

two days rioting tore through St. Louis's normally quiet brick streets;

thousands fled the "Black Dutch" government troops who many frightened

residents believed were "shooting women and children in cold blood."

|

FEDERAL TROOPS DRILL AT CAMP JACKSON IN MAY 1861. (USAMHI)

|

|

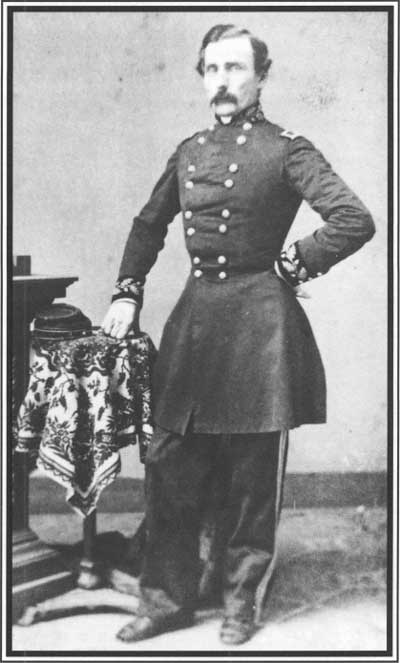

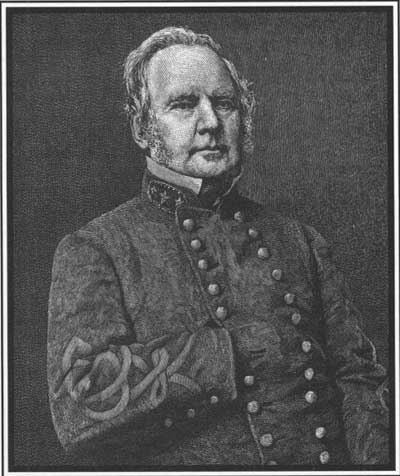

GENERAL DANIEL M. FROST (GS)

|

The "coup de tat at St. Louis," as one Missourian referred to

the Camp Jackson affair, was perhaps the single most catalytic event in

the state's history. Termed by one contemporary "the greatest military

blunder of the Civil War"—phraseology that historians have echoed

since—the action galvanized Missouri's countryside, turning

thousands of residents who had recently given support to the federal

government into strong southern rights advocates. By representing that

government as a coercive power, the military junto in St. Louis now

caused shoestring Unionists to regard them—and not the

Confederates—as warmongers. "Frank Blair is dictator," moaned one

resident, "and if the slightest show of resistance is made we will be

crushed out," while another predicted that "the rain of perfect teror

[sic] has commenced." Even Unconditional Unionists now found their

allegiance tested, if not ended, in the aftermath of Camp Jackson. Uriel

Wright, a member of the convention that had voted so decisively against

secession, declared emphatically: "If Unionism means such atrocious

deeds as I have witnessed in St. Louis, I am no longer a Union man."

Within hours of the incident, news of the federal coup reached the

state capital. The legislature was in special session, debating a

military bill that Jackson had requested that would have given him

unprecedented power to mobilize the state for war. Late in the

afternoon, the governor himself rushed into the chamber, fresh from St.

Louis, where he likely had witnessed the repercussions of the Camp

Jackson fracas, and relayed the news to several confidants. Within

fifteen minutes the legislature had passed Jackson's long-debated

military bill and soon adjourned. Just after midnight, summoned by the

alarming peals of church bells that Jackson had ordered rung,

legislators met again in emergency session amid rumors that three

regiments of federal troops were heading for Jefferson City. In wild

haste, the armed and anxious state legislature passed another act

declaring that "the City of St. Louis has been invaded by citizens of

other states, and a part of the people of said city are in a state of

rebellion against the laws of the state," and granting the governor

sweeping military powers "to take such measures as in his judgment he

may deem necessary or proper to repel such invasion or put down such

rebellion." Anxious legislators—including the governor—sent

their families from the state capital in anticipation of a federal

advance. Within a week, the legislature had given Jackson authorization

to take possession of the state's railroads and telegraph lines

"whenever in his opinion the security and welfare of the State may

require it" and requested that Jackson mobilize the state militia.

Missouri careened toward another type of conflict: a war within a

war.

|

THIS WOOD ENGRAVING TITLED TERRIBLE TRAGEDY AT ST. LOUIS APPEARED

IN THE MAY 25, 1861 NEW YORK ILLUSTRATED NEWS. (NPS)

|

Governor Jackson's gambit had worked, at least for the moment, for

virtually all of the state's newspapers condemned the Camp Jackson

capture. The governor quickly sought to capitalize on the emotion

surrounding Missouri's apparent atavism. Within minutes of passage of

the legislature's late-night defense act, Jackson dispatched squads from

the newly reorganized state militia (now called, fittingly, the Missouri

State Guard, and soon to number as many as two thousand, though poorly

if at all armed) in Jefferson City to guard and if necessary to burn the

railroad bridges spanning the Gasconade and Osage Rivers. He ordered the

state's powder stores dispersed around the countryside to militia

commanders throughout the state, removed the state's treasury funds, and

appointed Sterling Price—a former Mexican War general and governor

who had recently chaired the secession convention but who now, in the

aftershock of Camp Jackson, had cast his lot with the governor—as

commander of the State Guard. Called "Old Pap" by the militia, Price was

enormously popular in the state, and his appointment offered

legitimacy—both from his martial experience and his moderate

politics—to both the Guard and the governor's effort to mobilize

the state.

|

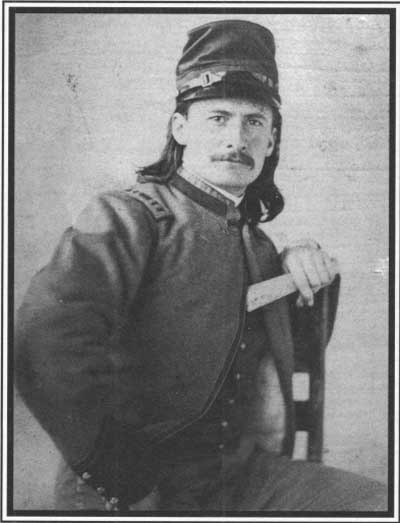

CAPTAIN EMMETT MACDONALD OF THE MISSOURI STATE MILITIA WAS CAPTURED AT

CAMP JACKSON BUT REFUSED PAROLE. (GS)

|

|

THIS NEWSPAPER ILLUSTRATION DEPICTS UNITED STATES VOLUNTEERS ATTACKED BY

THE MOB, CORNER OF FIFTH AND WALNUT STREETS, ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

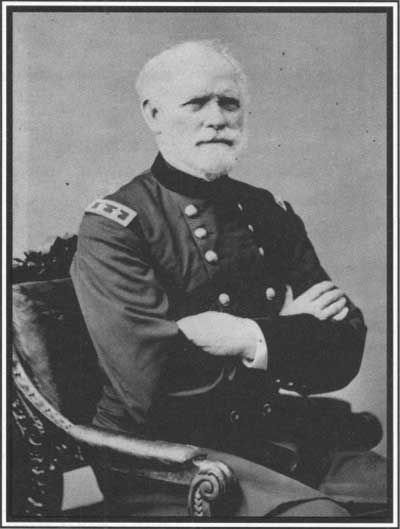

As extremists inflamed the state, moderates attempted to bring order

to the onrushing chaos. State Guard commander Sterling Price traveled to

St. Louis to meet with the conservative commander of the federal

Department of the West, General William S. Harney, who had returned to

the city in the aftermath of Camp Jackson and was horrified at the

results of Lyon's rash act. A Tennessean, Harney was well-regarded in

the army as a Plains Indian fighter whose long career and unquestioned

loyalty could effect peace in the volatile state. On May 21, Price

worked out an agreement with Harney that maintained the fragile balance

between state and federal authorities in the state. So long as the state

government kept order in Missouri, federal troops would not intervene

militarily in its affairs and then only in cooperation with the state

troops. "The united forces of both governments," read the proclamation,

"are pledged to the maintenance of the peace of the State, and the

defense of the rights and the property of all persons without

distinction of party." Harney in effect, had pledged the federal

government's own neutrality in Missouri.

|

MISSOURI STATE GUARD

The Missouri State Guard, victorious at Wilson's Creek, was the

militia guaranteed to Missourians under the Second Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. Created by the Missouri legislature

on May 11, 1861, the Guardsmen swore allegiance to their state and were

authorized to carry only the Missouri flag. Their commander, Major

General Sterling Price, initially pledged to defend the state against

all incursions, whether from the North or the South. Governor Claiborne

Fox Jackson hoped to use the State Guard as the nucleus of a Confederate

army in Missouri, and most of the State Guard's officers and many of its

men favored secession. Historian E. B. Long expressed it best: "Nothing

was clear cut — it was simply Missouri." The Missouri State Guard

was born amid controversy. It existed as a separate entity of

significant size for only a brief time, as almost all of its members

voluntarily transferred to the Confederate army during the fall of 1861,

after the Confederate Congress voted to admit Missouri to the southern

nation. Thousands refused Confederate service, however, either from a

desire to end their military careers or because they had never

considered themselves as fighting for anything but their home state.

During the first months of the war the State Guard was a major strategic

factor in the Trans-Mississippi theater. From its ranks came several

soldiers who rose to prominence, such as Sterling Price, Jo Shelby, and

John S. Marmaduke.

An appreciation of the Missouri State Guard must begin with the

complex events that brought it into being. When the Civil War broke out

following the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861, Governor Jackson

rejected President Abraham Lincoln's call for state militia to put down

the "rebellion." Instead, early in May 1861, he called units of the

pro-secessionist Volunteer Militia of Missouri into camp at St. Louis,

thereby potentially threatening the St. Louis Arsenal, the largest

repository of weapons west of the Mississippi River. The commander of

the arsenal, Captain Nathaniel Lyon, took no chances. On May 10 he

marched out with a small party of U.S. Army Regulars and a large number

of volunteers. They captured the Volunteer Militia without a fight, but

while the prisoners were being marched back through the streets of St.

Louis a riot erupted in which more than two dozen civilians were killed.

The Volunteer Militia were eventually paroled.

|

MAJOR GENERAL STERLING PRICE (BL)

|

Lyon's actions brought the Missouri State Guard into being. Despite

its prosecessionist leanings, the Missouri Volunteer Militia had

violated neither state nor federal law, while Lyon's volunteers had been

raised and armed illegally. The federal commander seemed bent on making

war against a state that had not left the Union. In response, the

Missouri legislature passed laws reorganizing the county-based militia

guaranteed to the state by the Bill of Rights, giving it the name

Missouri State Guard.

The structure and organization of the new State Guard itself was for

the most part quite ordinary. The governor was its commander in chief.

He was assisted by a personal staff and a Military Board, which was to

draw up rules and regulations for the Guard and oversee its

administration. In times of "insurrection, invasion, or war," the

governor could appoint a major general to command all forces in the

field. The state was divided by counties into nine districts, and the

troops therein were assigned to a correspondingly numbered division.

Thus "First Division, Missouri State Guard," was a geographic,

organizational term and did not denote the number of soldiers in the

command. Each division was commanded by a brigadier general, initially

appointed by the governor. These officers were charged with enrolling

the local citizens and organizing them into military units. After a

minimum of twenty-four companies were organized, the soldiers therein

were to elect a brigadier general, who would replace the governor's

appointee and serve for good behavior. Each division was to maintain

infantry, cavalry, and artillery, raised at the company level and

organized first into battalions and then into regiments. While the types

of arms were to be separate on paper, the regulations allowed them to be

combined for expediency under the most senior officer present. Thus

while on actual service a single battalion of the State Guard might

contain not only foot soldiers but also mounted men and attached

artillery. It was a highly flexible, community-based structure,

following the American militia tradition, which dated to colonial

times.

All physically fit free white male residents between the ages of

eighteen and forty-five were subject to duty in the State Guard.

Enlistees served for seven years, during which time they could be called

up for both annual training and emergency service. If field service

exceeded six months, the commander in chief was to apportion troops so

all nine divisions contributed. Volunteers were desired, but division

commanders had the power to institute a draft. Persons drafted could

escape service by paying a commutation of $150. Interestingly,

volunteers under the age of twenty-one needed written permission from a

parent or guardian to enlist but could be drafted without their

consent.

With peak strength of about twenty-five thousand men scattered

across the state, the Missouri State Guard forced the Federals to

concentrate more than sixty thousand men in Missouri from May through

November.

|

Following the Battie of Wilson's Creek and the siege of Lexington,

Missouri, the Confederate Congress voted to admit Missouri and Sterling

Price began transferring his men to Confederate service. This marked the

end of the most important phase of the State Guard's existence. For a

period of over twenty-nine weeks these American citizens in Missouri had

opposed the power of the federal government. With peak strength of about

twenty-five thousand men scattered across the state, the Missouri State

Guard forced the Federals to concentrate more than sixty thousand men in

Missouri from May through November. Had those Union soldiers been

available for service elsewhere, the first year of the war might have

gone differently for the North.

Thousands of Missourians who had been members of the State Guard took

part as Confederate soldiers in the various campaigns in Missouri,

Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama between 1862

and 1865. Price commanded Missouri Confederates at the Battle of Pea

Ridge in March 1862 and the unsuccessful campaign to defend Little Rock

in the summer of 1863. In September and October 1864 he led a raid

across Missouri designed to disrupt federal operations and gain

recruits. Only partially successful, it was the longest cavalry raid in

American military history. Former State Guardsmen were also caught up in

the guerrilla fighting that plagued much of the Trans-Mississippi

region.

The Missouri State Guard contributed significantly to the leadership

of the Confederate cause. Generals Daniel Frost, Martin Green, Mosby

Parsons, Sterling Price, and William Slack obtained equal rank in the

Confederate army. Other Guardsmen who eventually wore a general's star

were John B. Clark, Jr., Francis Cockrell, Basil Duke, Henry Little,

John S. Marmaduke, James Major, and Joseph O. Shelby.

— by William Garrett Piston and Thomas P. Sweeney

THIS IS A CONDENSED VERSION OF AN ARTICLE FROM THE JUNE 1999 ISSUE OF

NORTH & SOUTH MAGAZINE.

|

The action cost the veteran general his command. Just a week after

the Harney-Price agreement, Frank Blair managed to obtain orders from

the War Department relieving Harney of command of the western

department, which Lyon would assume in the interim. Radicals would now

move federal authority in Missouri. The effects would be both immediate

and catastrophic. Seeking to buy time with Lyon in charge, Jackson

solicited a meeting with the federal commander, now a brigadier general

of volunteers. On June 11, Lyon and Blair, accompanied by an aide, met

with the state leaders in the governor's suite at the Planters' House, a

sumptuous hotel in St. Louis, Unlike Price's interview with Harney, this

meeting was anything but cordial. For the first half hour, Jackson and

Price spoke conciliatively, proposing strict neutrality and offering

such concessions as the disbanding of the State Guard and discontinuance

of further militia musters in return for the same for the Home Guard now

under federal arms. Quickly, Lyon came to dominate the meeting, refusing

to concede any point on federal authority, rejecting the state leaders'

calumet. After four heated hours, Lyon declared bluntly, "Better, sir,

far better that the blood of every man woman and child within the limits

of the State should flow, than that she should defy the federal

government. This means war." Turning on his heels, Lyon strode

briskly out of the room, leaving the remaining five men in stunned

silence. The governor and militia commander hastened back to Jefferson

City.

|

GENERAL WILLIAM S. HARNEY (MHS)

|

Neither Claib Jackson nor Sterling Price could have predicted Lyon's

peremptory declaration of war. Yet clearly they understood its

implications in the fullest sense. Hastening back to Jefferson City and

ordering the destruction of the Gasconade River bridge and the cutting

of the telegraph wires in the event Lyon would send troops, the governor

prepared a proclamation for public release the following day. Now

presented with the opportunity to bring to fruition his

passive-aggressive strategy for Missouri's secession, Jackson used the

proclamation to reiterate the theme that he was confident would sound

most clearly among the state's residents: that the federal government

was the aggressor bent on coercing peaceable Missouri. The governor

called for fifty thousand militia volunteers "for the protection of the

lives, liberty, and property of the citizens of this State. . . . Rise,

then, and drive out ignominiously the invaders who have dared to

desecrate the soil which your labors have made fruitful, and which is

consecrated by your homes."

|

|