|

AFTERMATH

The Battle of Wilson's Creek, or Oak Hills, as federals and

Confederates, respectively, called it, was the first major battle of the

war after Bull Run. Unlike the battle in Virginia, in which casualties

were light when compared to the number of troops involved, the fight at

Wilson's Creek was bloodier than anyone could have imagined. In the

brief six and a half hours of fighting, Lyon's Army of the West suffered

285 killed, 873 wounded, and 186 missing, or 1,317 out of 5,400 men

involved (a 24.5 percent casualty rate), while McCulloch's Western Army

incurred 277 dead and 945 wounded, or 1,222 losses of more than 10,200

men (a 12 percent casualty rate). Both in total numbers and as a

percentage of the force engaged, Lyon's losses were greater than those

of any battle in the Mexican War, while McCulloch's were higher than all

but three battles in that war. Taken together, the 16 percent casualty

rate was one of the highest of the Civil War. When viewed in light of

the fact that the battle was fought between forces consisting

overwhelmingly of untried recruits, of which nearly half were armed with

no more than shotguns or hunting rifles and of which several thousand

were completely unarmed and never took part in the battle, the

statistics are particularly telling. As one participant aptly remembered

the battle, it was one "mighty mean-fowl fight."

|

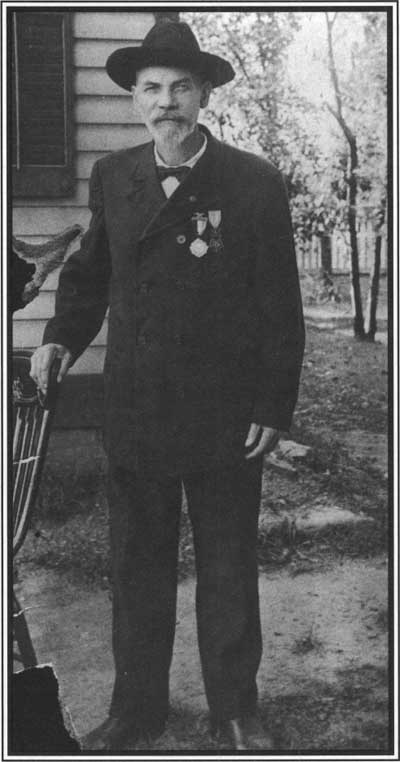

NICHOLAS BOUQUET OF THE FIRST IOWA WAS A RECIPIENT OF THE MEDAL OF

HONOR. THIS PHOTOGRAPH WAS TAKEN CIRCA 1905. (NPS)

|

News of Wilson's Creek and of Lyon's death made headlines across

the country, evoking conflicting responses. Despite the initial banner

of the New York Times, which proclaimed the battle a "Great National

Victory in Missouri," the actual results soon made for somber reading

among Unionists.

|

News of Wilson's Creek and of Lyon's death made headlines across the

country, evoking conflicting responses. Despite the initial banner of

the New York Times, which proclaimed the battle a "Great National

Victory in Missouri," the actual results soon made for somber reading

among Unionists. Barton Bates wrote to his father, Edward, attorney

general for the Lincoln administration, that "General Lyon's death cost

us much popular strength throughout the state." Many were discontented

by what they perceived to have been Frémont's wanton sacrifice of

Lyon, while others questioned Lyon's rash strategy. Prosouthern

Missourians rejoiced at the news. "Lyon, the king of the beasts, the

Camp Jackson HERO, the murderer of innocent women and children and

as I believe under the displeasure of God," wrote one such embittered

Missourian, "has met his just reward."

The victorious Missouri State Guard remained in Springfield, while

McCulloch and Pearce returned to Arkansas, the breach between the State

Guard and Confederate commanders having widened in the days immediately

following the battle. In September, Price marched his force northward,

intending to retake the Missouri River and his home. On September 20,

with exiled governor Jackson in attendance, Price—his ranks swelled

to twenty thousand troops—captured a three-thousand man Union

garrison under Colonel James A. Mulligan at Lexington. Together, the

victories at Wilson's Creek and Lexington marked the high-water mark of

secessionist hopes in Missouri. With nearly thirty-eight thousand troops

massing on his flanks, Price could not remain in Lexington and retreated

to Cassville. Protected by Price's force, in October a rump assembly of

the state legislature met at Neosho and passed an act delivering

Missouri into the Confederacy, which eventually admitted it as its

twelfth state. Jackson had achieved his long-sought secession, but the

gesture was meaningless. Without control of the seat of power and with

the federal government firmly controlling St. Louis, the state would

remain in Union hands. Sterling Price ultimately left the state,

fighting with his State Guard in Arkansas at Pea Ridge (where McCulloch

was killed) and serving with the Confederate army in northern

Mississippi. In 1864, he led a massive armed cavalry raid back to the

state, in hopes of diverting federals from Georgia and redeeming his

home state from Union hands. Instead, a combined federal campaign drove

Price once again from the state's borders. With the exception of that

and separate cavalry raids by John S. Marmaduke, Jo Shelby, and M. Jeff

Thompson, Price's retreat from Lexington in the fall of 1861 marked the

last real show of Confederate force in Missouri.

|

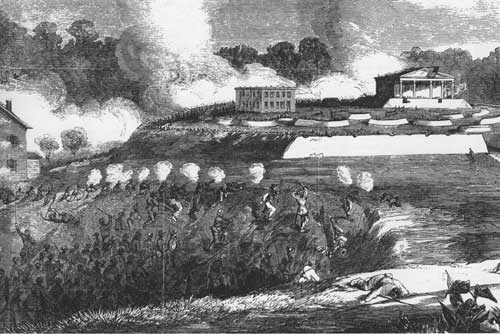

THE BATTLE OF LEXINGTON, MISSOURI WAS FOUGHT SEPTEMBER 18-20. (HW)

|

In October 1861, Frémont found himself plagued by the fallout

from Wilson's Creek. Continuing as department commander, the Pathfinder

received vehement criticism for his abandonment of Lyon. Though Frank

Blair initially lay blame for Lyon's defeat and death on "red tape and

Quartermasters Department," he soon led the storm of protest against

Frémont. He would ultimately appear before Congress's Joint

Committee on the Conduct of the War and excoriate his family's former

friend. By that time, the Pathfinder had left Missouri after angering

Lincoln with a premature emancipation proclamation in the state. On

November 2, Frémont received the order for his removal by courier

as he led troops in pursuit of Price following the battle at Lexington.

He gave up his command at Springfield, the scene of Lyon's death.

Perhaps most dramatic were the effects of Lyon's campaign and

Wilson's Creek on the Missouri populace. By polarizing the state, Lyon

and Blair provided guerrilla bands with a cause célèbre

for which they subjected large areas of Missouri to three years of

rampant bushwhacking, sniping, hit-and-run raiding, arson, and murder.

The truest demonstration of the improbable oxymoron civil war was

nowhere more apparent than in Missouri, its brutal guerrilla war

unsurpassed in its fury and scope in the entire national conflict.

Pro-Confederates such as William Quantrill, "Bloody" Bill Anderson,

Jesse and Frank James, and George Todd gained notoriety by unleashing

bloodthirsty attacks on Unionist residents, while pro-Union Jayhawkers

like James H. Lane, James Montgomery, and Charles Jennison led

retaliatory raids that often equaled their rivals in their destructive

fury. More than any other state, Missouri suffered the horror of

internecine warfare that, almost as Lyon had predicted at the Planters'

House, touched every man, woman, and child living there in some way

during the next three years and beyond. The Battle of Wilson's Creek

offered the first unleashing of that coming fury.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

Wilson's Creek

|

|

Back cover: The Death of Lyon, Kurz and Allison lithograph

(NPS collection).

|

|

|