|

THE DEATH OF LYON

After nearly three-quarters of an hour of inactivity, Price ordered a

second attack, and his line of battle emerged from the brush and prairie

grass. The federal line, poised for another assault, responded

immediately. Lyon had put the remainder of Plummer's battalion, now

returned from their foray across the creek, in reserve with every other

infantry unit now in line of battle. Altogether, Lyon had some 3,500 men

and ten pieces of artillery positioned to meet the ensuing attack. For

the next hour, according to Sturgis, the fighting was "almost

inconceivably fierce along the entire line." The southern units were

often in formations three or four ranks deep, with the first rank lying,

the second rank kneeling, and the third (and sometimes fourth) rank

standing, all firing together. The massed fire on both sides at close

range increased casualties dramatically.

As the firing increased, white smoke began to obscure the field, and

by mid-morning, the heat had become frightful. Bloody Hill had at the

time few trees of any consequence, mostly clumps of scrub oaks in the

midst of chest-high prairie grass, with occasional thickets, and in the

open terrain men fell from both wounds and heat exhaustion. Lulls

settled periodically over the battlefield, marred only by desultory

firing, as if both armies needed to catch their breath and take precious

water before resuming the desperate struggle. Then the great crash of

musketry would resume almost spontaneously to continue with wavelike

intensity until another respite mysteriously occurred. The tall grass,

the soldiers' relative inexperience, and, above all, the scarcity of

ammunition conspired to slow the pace of the combat. Many on both sides

used the grass as a shield, firing and reloading while either kneeling

or lying down, despite their lack of practice in such techniques and the

extra time it took to do so.

|

A POSTWAR ILLUSTRATION OF BLOODY HILL FROM THE EAST. (BL)

|

|

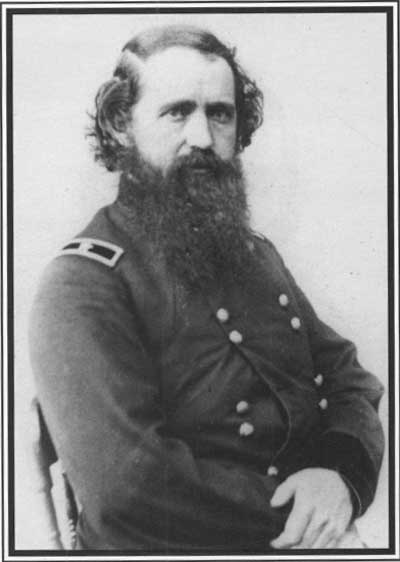

LIEUTENANT WILLIAM WHERRY. (NPS)

|

Lyon's troops bore up well under the withering fire and intense

August heat. Their commander did not fare as well. Having dismounted

from his dapple-gray horse, Lyon directed the battle on foot, leading

his mount by the reins. A career army captain, he was accustomed to

leading troops at the front, not as a general at the rear. As he walked

close to the lines, a bullet grazed his right calf, a painful if not

serious wound that required treatment to stop the flow of blood. Shortly

thereafter Lyon's mount was shot, sank to its haunches, and died.

Throughout, Lyon kept his worn captain's frock coat buttoned up to his

chin. Limping now, and waving his hat and sword to encourage his troops,

he suffered a second wound when a bullet brushed the right side of his

head. Blood ran profusely down his face and became matted in his sweaty

hair and beard. Pale and dazed, he moved to the rear, found a relatively

safe spot, and sat down. An officer offered a handkerchief and bound the

general's head. Totten noticed his commander's wound and offered Lyon

brandy from his canteen, but he somberly declined. When Schofield

arrived, Lyon was despondent. "It is as I expected," he moaned, "Major,

I am afraid the day is lost." Schofield replied, "No, General; let us

try it again." Encouraged by Schofield's enthusiasm, Lyon revived,

determined to continue the fight.

Believing this his last chance for victory, Lyon intended to lead a

fresh assault. Taking the mount of one of Sturgis's orderlies, blood

dripping from the heel of his boot, Lyon rode forward to deal with

problems at the federal center. Followed by his aide, Lieutenant William

M. Wherry, and six to eight orderlies, Lyon rode past the right end of

the First Iowa's line to close a gap between it and the First Missouri.

When his aides attempted to dissuade him from exposing himself so

precariously to fire, Lyon replied firmly, "I am but doing my duty." The

federal commander observed a group of horsemen with the enemy's infantry

to the left, one of whom Lyon recognized as Price, commander of the

Missouri State Guard, wearing a long white linen duster and a plain

white felt hat. Starting toward the horsemen, Lyon ordered his escort to

"draw pistols and follow." Wherry managed to convince his fiery leader

that the attempt would be too risky and suggested instead that some

troops be brought forward.

|

DEATH OF GENERAL NATHANIEL LYON AT THE BATTLE OF WILSON'S CREEK,

SPRINGFIELD, MO., AUGUST 10TH, 1861. ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S

WEEKLY. (FW)

|

At near 9:30 A.M., Lyon returned to his lines, and the Iowans called

for the general to lead them. When Sweeny came up, Lyon initially

directed him to take charge of the Iowans. Pulling the Second Kansas out

of line, Lyon moved them in column behind the First Missouri and into

the gap. He then decided to lead the troops personally. Riding with the

reins in his left hand and his felt hat in his right hand, Lyon turned

back to his right, waving his hat and crying, "Come on my brave boys, I

will lead you! Forward!" At that moment a volley exploded from the thick

undergrowth in the troops' immediate front. A large-caliber bullet,

fired from only a few yards, tore into the left side of Lyon's chest

below the fourth rib, passed through both lungs and the heart, severing

the aorta, and exited just below the right shoulder blade. According to

one source, the wounded general attempted to dismount but began to fall

from the saddle. Private Albert Lehmann, the general's personal aide,

rushed to catch Lyon as he collapsed. Cradling Lyon's head against his

shoulder, the orderly tried to stop the profuse flow of blood. The

general gasped for breath, then whispered hoarsely, "Lehmann, I am

going." He then expired, amid the smoke and din of battle. According to

another eyewitness, Lyon died instantly upon being hit, and fell

backward from his horse to the ground, without any last words, a version

perhaps substantiated by a pencil sketch by Henry Lovie, an artist

covering the campaign for Frank Leslie's illustrated Newspaper.

In either case, Lyon was the first Union general officer to be killed in

battle in the Civil War.

|

COLONEL ROBERT BYINGTON MITCHELL, COMMANDER OF THE

SECOND KANSAS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY. (GS)

|

The fight raged on around the general's death site. Captain Samuel J.

Crawford of the Second Kansas, later governor of the newest state,

remembered, "We fired over Lyon's body, and three or four of [the] men,

as they lay wounded." Few of the troops likely realized their commander

had fallen, and after twenty minutes, the Kansans managed to drive the

southerners in their front from the crest of Bloody Hill. Yet another

lull ensued, during which Lieutenant Gustavus Schreyer and a detachment

of men retrieved the dead and wounded, finding Lehmann clutching his

commander's hat and bemoaning his death. As they carried Lyon's body to

the rear, Wherry arrived and, fearing that news of the general's death

might affect the men, decided to conceal the fact for as long as

possible. He had the coattails of Lyon's tunic pulled over the general's

face and ordered the body placed under the shade of a small blackjack

oak, in a sheltered spot not far from Du Bois's guns. Wherry then

located Schofield, informed him of Lyon's death, and Schofield rode off

to inform Sturgis the senior regular army officer, that the forces upon

Bloody Hill were now under his command.

|

|