|

THE GRAND STEEPLE CHASE

Jackson's despondent troops trudged southward, joining with troops

under Price from near Lexington while leaving behind an undetermined

number of recruits from northern Missouri who had been unable to reach

Boonville before Lyon's preemptive strike. After pausing briefly at

Warsaw (where Jackson sent Price southward to assist other emissaries in

the enlistment of aid from Arkansas Confederates and to recruit in

southern Missouri), the State Guard forces converged near Lamar. A

number of trailing recruit companies and hundreds of individuals joined

them throughout the march, as the column of nearly six thousand—a

third of whom were unarmed—quickly moved southward through steady

rains that impeded their progress.

The weather actually proved a blessing for it delayed Lyon's pursuit

even more than it did the governor's forces. Lyon remained at Boonville

for nearly two weeks to gather supplies, horses, and wagons for his

campaign which, because of his hasty departure from St. Louis and his

choice of a river expedition, he lacked. With just seventeen hundred

troops and an entire river to garrison, Lyon was in need of

reinforcements from St. Louis and Kansas. He also was hampered by the

quartermaster at St. Louis, who confiscated most of the wagons and mules

procured for his expedition, forcing Lyon to gather what makeshift

transportation he could from around Boonville. By the time he ordered

his troops out of camp, he contended with flooded rather than merely

rising rivers, as Jackson's men had faced in the past few days.

|

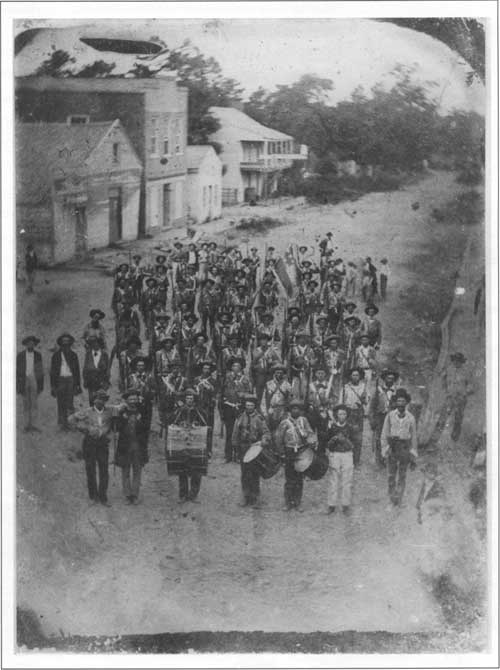

COMPANY H OF MCRAE'S THIRD ARKANSAS PHOTOGRAPHED AT ARKADELPHIA IN JUNE

1861. (GS)

|

At Lamar, former Missouri senator David Rice Atchison joined the

governor's staff as principal aide, boosting the troops'—and the

governor's—morale, and Jackson used the time to organize his

command more thoroughly. Striking out at daybreak on July 5 (two days

after Lyon left Boonville), Jackson's State Guard columns were

approaching Carthage when they encountered the southwest force of Lyon's

expedition under Sigel, the Third and Fifth Regiments of Missouri

Volunteers and Backof's eight-gun artillery battery, totalling some

eleven hundred men. After a sharp fight, the armed contingent of State

Guard troops—who alone outnumbered Sigel's men four to

one—nearly surrounded the federals before the latter retired in

good order from the field. Jackson's Guard pushed on toward Neosho and

the next day met up with Sterling Price, who had convinced the commander

of Confederates in northern Arkansas, Brigadier General Ben McCulloch,

to enter southwest Missouri and advance against Sigel. The three men

determined that Jackson and Atchison could now best serve their state by

diplomacy, rather than direct leadership. After assisting Price in

encamping the state troops at Cowskin Prairie, in McDonald County, the

governor, a small cadre of aides, and the former senator left the state

on July 12, traveling south through Arkansas's Boston Mountains toward

Little Rock. On the morning of July 19, the Arkansas governor, Henry

Rector, received the two men at the state capital, and that evening,

though weary, Jackson addressed an enthusiastic audience. Next morning,

he and Atchison pushed on toward Memphis, convincing the Confederate

commander there, General Leonidas Polk, to send troops into southeast

Missouri. Jackson and Atchison then left Memphis by train for Richmond,

Virginia, the new Confederate capital, to solicit Confederate

intervention in Missouri.

|

AUGUST 1861 ILLUSTRATION OF THE BATTLE OF CARTHAGE, MISSOURI. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

On July 22, the same day that Jackson reached Memphis, the Missouri

state convention met again in emergency session in Jefferson City. The

commitment to conciliation that had pervaded the initial convention was

not so evident in this subsequent meeting; the atmosphere was fractious

and contentious nearly from the outset. Unionists quickly sought to

declare vacant the "expatriated" executive branch, which had committed

treason for defying federal forces, and moved to fill those state

offices now open, including those in the General Assembly. With some

opposition, the seventy-five-member convention voted to amend the state

constitution so as to replace the exiled state officials and abrogated

the Military Act that the legislature had recently passed under duress.

The convention then seated Hamilton R. Gamble as provisional governor,

Willard P. Hall as lieutenant governor, and Mordecai Oliver as secretary

of state—all staunch Unionists. This administration would maintain

steadfast support for the federal government for the duration of the

war, In practical terms, Claiborne P. Jackson was little more than

Missouri's "Governor in the saddle."

Had Lyon's campaign ended at this point, it would have been viewed as

an unquestioned success. With lightning speed, he had captured the state

capital and chased the secessionist governor and many of his

conspiratorial legislators from their seat of power, effectively

eliminating any chance of their further promoting the state's secession.

With scant losses, he then dispersed a sizable force of the State Guard,

the primary threat to federal authority in Missouri, and blocked a large

contingent of future recruits from reaching the main body of prosouthern

forces. Moreover, from a military standpoint, the movement of Lyon's

wing of the campaign had alone accomplished all that was strategically

necessary to secure Missouri. By occupying the Missouri River line, Lyon

controlled most of the state's population, agriculture, industry, and

wealth, as well as the transportation lifeline of Missouri (both river

and rail) that would allow the federal troops to concentrate superior

forces quickly at any point between St. Louis and Fort Leavenworth,

Kansas, both fortified and in federal hands. His southwestern campaign,

regardless of the outcome at Carthage, had secured the rail line to

Rolla, thus giving federals control of virtually the entire rail network

in Missouri. Lyon's campaign had already provided the federal government

all it needed strategically to keep Missouri in the Union.

|

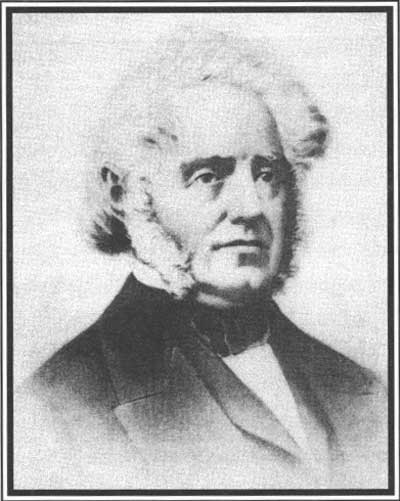

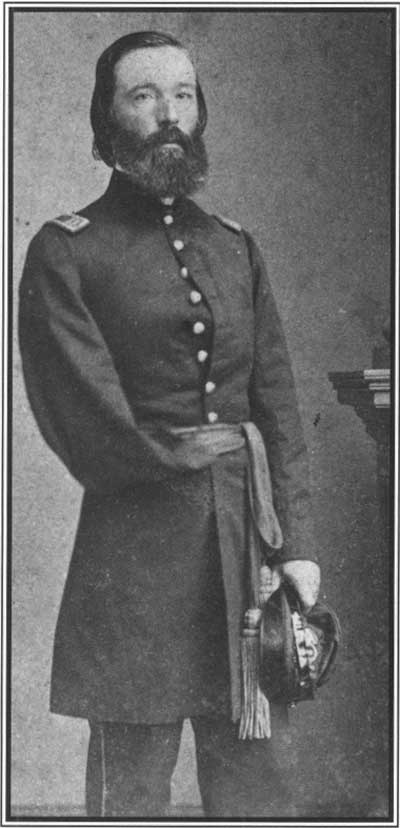

GOVERNOR HAMILTON R. GAMBLE (NPS)

|

|

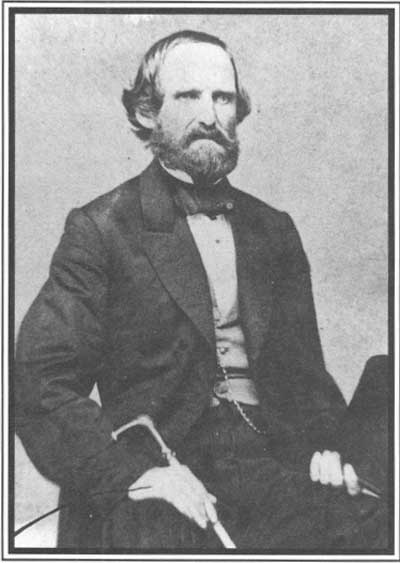

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN C. FRÉMONT (BL)

|

Whether Lyon recognized the strategic importance of his coup is not

known. Despite his successes and the national praise be had received,

Lyon was not yet satisfied. Believing he had been "too mild" with

Missouri's secessionists, he intended now to "deal summarily" with the

governor's fleeing forces. As a newspaper correspondent covering the

Missouri campaign wrote, Lyon denounced the treason of the state's

secessionists and "asserted with vehemence that no punishment was too

great for that crime." At all costs, and above and beyond any strategic

consideration, Lyon was determined to inflict requisite punishment on

secessionists for their crime against the nation. Lyon was no longer

directing a military campaign; he was now leading a punitive crusade.

As Lyon prepared to pursue Jackson's militia southward, controversy

over the events in Missouri swirled well outside the state's borders. A

phalanx of moderate Missouri politicos lobbied the Lincoln

administration to name a new commander of the Department of the West.

Though the Blairs exerted similar pressure to allow Lyon to continue as

acting commander, Army general in chief Winfield Scott had reservations

about his rash actions. Fearing Lyon's removal, the Blairs convinced the

War Department to name John C. Frémont, a close personal friend

of the Blair family, as department commander. They were confident that

Frémont would sustain not only Lyon but radical Unionist

leadership in Missouri. The close call also convinced Frank Blair to

relinquish command of a brigade in Lyon's Army of the West and assume

his congressional seat in Washington, where he could better protect

Lyon's flank.

Having arranged for the transfer of the First and Second Kansas

Volunteers as well as cavalry (totaling some 2,200 men) under command of

Major Samuel D. Sturgis, a West Pointer and Mexican War veteran, and

buoyed by the arrival of the First Iowa, Lyon's column of 2,354 set out

from Boonville on July 3. Slowed by mud and continued rains, the troops

did not reach Clinton, on the Grand River, until early in the afternoon

on July 7, where they met Sturgis's force. The river was a torrent, and

the crossing took more than a day, during which Lyon learned of Sigel's

withdrawal at Carthage. Lyon force-marched the combined force, now

totaling some 4,500 troops, toward the Osage, twenty-five miles distant.

They slowly crossed the swollen Osage on July 10, losing men and horses

to drowning and abandoning their tents and other equipage. The rains now

had subsided, and the heat became ferocious. Lyon pushed his troops

relentlessly, with only hardtack for provisions. Despite their

commander's constant vigilance, hundreds straggled, hopelessly fatigued

and many suffering heat stroke. His exhausted troops arrived outside

Springfield on July 13, having learned that the State Guard had moved on

to Cowskin Prairie, in the extreme southwestern corner of the state.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL BEN MCCULLOCH (GS)

|

|

A VIEW OF SPRINGFIELD, MISSOURI, FROM THE SEPTEMBER 1861 ISSUE OF

HARPER'S WEEKLY. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

As Lyon's column drove on toward Springfield, McCulloch—a former

Texas Ranger, Mexican War veteran, and at that time the only man holding

the rank of general in the Confederate army who lacked a West Point

education—entered Missouri. Though he had received orders from the

Confederate War Department cautioning against entering the neutral state

except under the most dire circumstances, and despite his skepticism of

the untrained and unarmed State Guard, McCulloch sent mounted troops

into the state as far as Neosho, capturing one of Sigel's detachments.

News of the governor's victory at Carthage sent the Texan with his

troops hastily back into Arkansas while Jackson and Price encamped at

Cowskin Prairie, where State Guard enlistees continued to swell the

militia's ranks. Price undertook personal training of his men and

detailed many to the nearby Granby mines, an abundant source of lead.

The once-rabble slowly began to resemble an army.

Meanwhile, Lyon occupied Springfield, with two thousand inhabitants

the largest town in the Ozark region. Lyon had envisioned the town as an

ending point of his campaign, a place for jubilant respite after the

destruction of the Stare Guard, Now, he found himself compelled to hold

a predominantly Unionist city against a much larger force. With Sigel's

troops from Carthage and Sweeny's arrival with 1,500 troops from St.

Louis, Lyon had an effective force of 5,868 along with three full

artillery batteries of eighteen pieces. Yet supplies were woefully short

and those that Sweeny arranged for had not arrived; the nearest railhead

was in Rolla, more than a hundred miles distant over rough terrain. The

troops needed shoes and clothing after the hard march from Boonville,

and most had not been paid since their enlistment. Particularly

distressing was that the ninety-day enlistments of nearly half of his

volunteers would soon expire. Having experienced the harshness and

deprivations of campaigning, many of the dispirited Home Guards—who

had enlisted to protect St. Louis, not to swelter in the Ozarks—now

would not reenlist for three years of government service. Others

declared openly that they wanted "a fight or a discharge." In a

thirty-six-hour span, Lyon sent most of two Reserve Corps regiments back

to St. Louis to be mustered out as well as receiving an order recalling

his regulars under Sweeny. Realizing he faced a potential crisis, Lyon

flooded the telegraph wires with requests for reinforcements from

Frémont, who would soon arrive in St. Louis. "See Frémont,

if he has arrived," he wrote desperately to an aide in St. Louis.

"Everything seems to combine against me at this point. Stir up

Blair."

|

CAPTAIN THOMAS W. SWEENY (KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

No assistance was forthcoming. Arriving on July 25, Frémont

was overwhelmed by the enormity of his new position. Threatened with an

imminent invasion of Missouri's Bootheel (which Governor Jackson had

helped to organize) and the potential loss of Cairo, Illinois, and even

St. Louis, the celebrated "Pathfinder of the West" saw Lyon's force

primarily as a defense to prevent Price's State Guard and Confederates

in northwestern Arkansas from advancing toward St. Louis to act in

concert with Gideon J. Pillow's "Army of Liberation," now occupying New

Madrid. Frémont was convinced that Lyon had enough troops to

repel an attack, and if not, he should withdraw to Rolla, claiming that

if Lyon should fight in the Ozarks, he would do so "only on his own

responsibility."

|

|