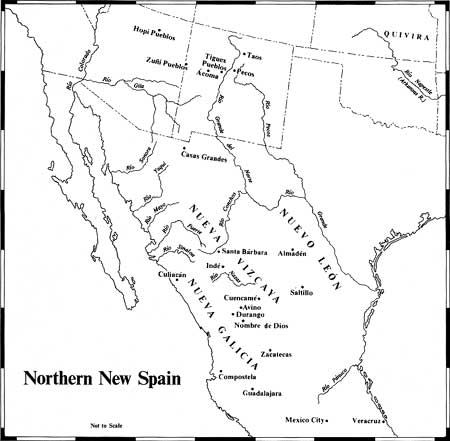

Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

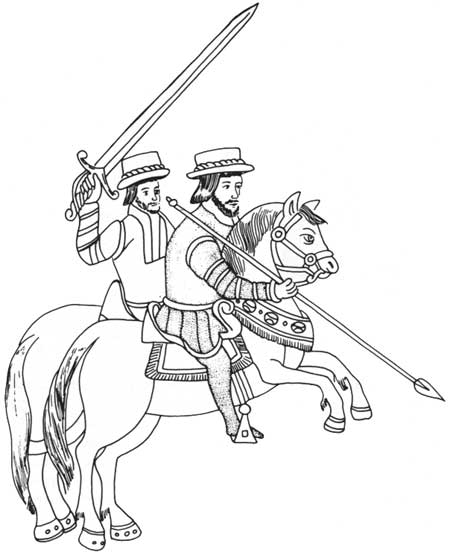

The First Spaniards It was early fall, the time when the maize plants begin turning brown, 1540. Twenty-two summers had passed since the conqueror Hernán Cortés first stepped ashore on the mainland of Mexico, to trade, he said. Now, eighteen hundred miles northwest of that dank tropical coast, a small column of helmeted Spanish soldiers marched across high, semi-arid country through arroyos, chamisa, and piñon to receive homage from the fortress-pueblo of Cicuye. Even though they numbered not many more than twenty, this medieval-looking detachment from the expedition of Gov. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado faithfully represented the conquering forces of Catholic Spain in America. The youthful captain, who wore a coat of mail and rode a horse covered with leather or quilted cotton armor, hailed his earthly Holy Caesarean Catholic Majesty in the same breath as his Heavenly Father. Having marveled firsthand at the incredible fruits of Cortés' success, he had willingly financed himself and his retainers for this venture of discovery. Several of the other horsemen had outfitted themselves and brought along black slaves. Behind them on foot marched four paid crossbowmen. Also on foot, in emulation of St. Francis, walked a gray-robed Spanish friar, a rigorous and visionary priest bent on conquest to the glory of God and the church militant. [1]

Capt. Hernando de Alvarado, from the northern mountain province of Santander, was probably light skinned with sandy hair and beard. In 1530, at age thirteen, he had crossed the Atlantic in the grand fleet that returned Cortés to México. He had served the conqueror, as he phrased it, "in the first discovery of the South Sea." Later, in the excitement of sensational reports from the far north, the well-born twenty-three-year-old Alvarado had signed on with Coronado as captain of artillery. During the battle for the Zuñi pueblo of Hawikuh, he and García López de Cárdenas shielded the fallen Coronado with their bodies and thereby saved the general's life. At least one chronicler later claimed that young don Hernando was kin to the more famous Pedro de Alvarado, hell-bent conquistador of Guatemala. [2]

At Alvarado's side rode Melchior Pérez. His father, Licenciado Diego Pérez de la Torre, had succeeded the notorious Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán as governor of Nueva Galicia. When the elder Pérez died in an Indian revolt, the viceroy appointed Coronado to the vacant governorship. The Pérez clan was from the villa of Feria in southern Extremadura just off the highroad between Zafra and Badajoz. Don Melchior had gambled a small fortune fitting out himself and his servants, more than two thousand gold castellanos he calculated. [3]

Juan Troyano, from the market town of Medina de Río Seco, northwest of Valladolid, had fought as a youth in the armies of Emperor Charles V in Italy. He had come to New Spain in the fleet that brought over Coronado and his patron, don Antonio de Mendoza, first viceroy of New Spain and heaviest financial backer of the expedition. Evidently Troyano possessed a flair for languages. He had already begun picking up phrases in various Indian tongues. He also, now or later, picked up an Indian girl, not unusual for a Spanish soldier. But Troyano refused to give her up, married her, and spent the rest of his life with her. [4] Unlike Troyano, Fray Juan de Padilla was profoundly disappointed in the Pueblo Indians, in all Indians for that matter. This belligerent Franciscan had joined Coronado for only one reason. He would, by the grace of God, find and reunite with Christendom the long-lost Seven Cities of Antillia. According to a popular romance of the time, seven Portuguese bishops fleeing the Moslem invasion of their homeland had embarked their congregations in the year 714 and sailed off to the west. They had founded seven immensely wealthy and utopian cities—cities that lay, Father Padilla was convinced, somewhere north from Mexico. Visits to both the Zuñi and Hopi pueblos had shattered his illusions that Cíbola or Tusayán might end his quest. Perhaps to the east, far to the east of Cicuye in the land of Quivira. A son of the Franciscan province of Andalucía in southern Spain, Father Padilla likely had been among the twenty friars shepherded to Mexico in 1529 by Fray Antonio de Ciudad Rodrigo, one of New Spain's revered original twelve. Padilla turned out to be a fighter as well as a visionary. He had joined earnestly in the war of Franciscan Bishop Juan de Zumárraga against the tyrannical first audiencia of Mexico, the ruling tribunal dominated by Nuño de Guzmán. He had taken part in the ill-starred venture of Cortés to build ships at Tehuantepec for exploration of the South Sea. He was quick tempered, obstinate, impatient, and, as the soldiers found out, a holy terror when aroused by swearing or alleged immorality. [5] Alvarado, Pérez, Troyano, and Padilla—these then, along with a handful of unnamed horsemen, crossbowmen, and servants, were soon to become the European discoverers of the populous stone pueblo of Cicuye. The Names Cicuye and Pecos Although most of the chroniclers of the Coronado expedition used variant spellings—Acuique, Cicúique, Cicuic—this word as spoken by the initial delegation from there, which sounded to Spanish ears like Cicuye, was probably the natives' own name for their pueblo. The people of Jémez, the only other Towa-speakers among the Pueblos, called Cicuye something like Paqulah or Pekush. That evidently became Peago, Peaku, or Peko among the Keres in between. From them, the Spaniards of don Gaspar Castaño de Sosa heard it forty years later. Hence the historic name Pecos. [6]

Cicuye was expecting them. Located as it was at the portal between pueblos and plains, the community had served for a century as a center of trade. Along with shells, buffalo robes, slaves, chipped stone knives, and parrots came news. The people of Cicuye must have learned of the Spanish presence along the gulf coast, of the Aztecs' fall, and of Nuño de Guzmán's rapacious forays up the west coast corridor soon after these events took place. They surely had heard reports of the itinerant white medicine man and his black spokesman—Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and Estebanico—as they and two companions made their tedious way from coast to coast across the whole of northern Mexico. The black had come north again swaggering. He had made demands on the Zuñis, and they had killed him. Cicuye knew the details. [7] Next, Spaniards with their awesome horses and firearms had appeared before Hawikuh and defeated the Zuñis, less than two hundred miles away. The headmen of Cicuye must have met in council. Should they stand against the invader or ally themselves with him for purposes of trade or war? It was a basic question that would later turn clan against clan and rend the social fabric of the pueblo. Initially, Cicuye sent a mission of peace.

Coronado Meets Bigotes At Hawikuh, Coronado had received them as foreign emissaries. They told the general that they had learned of the arrival of "strange people," in Coronado's words, "bold men who punished those who resisted them and gave good treatment to those who submitted." The inhabitants of Cicuye wished to be allies. Their spokesman, a large, well-built young man, evidently a war captain, was dubbed by the invaders Bigotes because, according to chronicler Pedro de Castañeda, he wore long mustaches. Such a display of individuality was unusual for a Pueblo Indian. Probably Bigotes was a trader, well traveled, experienced, and somewhat affected by his dealings with foreigners. He may even have spoken some Nahuatl, the lingua franca of central Mexico, which would have been readily understood in the Spanish camp. [8] The embassy from Cicuye exchanged gifts with Coronado: buffalo robes, native shields, and headdresses, for artificial pearls, glass vessels of some sort, and little bells. The Spaniards were particularly intrigued by the large hides covered with tangled and woolly hair. The men of Cicuye described the buffalo as best they could. They pointed to a painting on the body of a Plains Indian lad in their party, from which the Spaniards deduced that the animals were big cattle. To receive formal homage from Cicuye and to see these cattle, Coronado appointed the ready Captain Álvarado.

On the feast of the beheading of St. John the Baptist, August 29, 1540, Álvarado's squad had moved out from Zuñi, led by Bigotes and company. They had "discovered" invincible Acoma set on a rock twice as tall as the Giralda of Sevilla, then proceeded east to the cultivated valley of the Rio Grande, which they christened the Río de Nuestra Señora because they saw it first on September 7, eve of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin. They passed through the cluster of pueblos they called the province of Tiguex, and apparently traveled as far north as Taos, which Father Padilla thought might have had a population of fifteen thousand! Now in late September or early October, the first Europeans approached Cicuye. [9] A Spaniard's Description of Cicuye For an Indian pueblo, all agreed, it was impressive. "Cicuye," wrote chronicler Pedro de Castañeda,

Origin of Cicuye Ever since at least the thirteenth century by Christian reckoning, the upper Pecos River Valley had been a frontier of the Pueblo Indian civilization that flowered in the cliffs and valley floors to the west. While Spaniards under the sainted Ferdinand III took the offensive against the Moors, recapturing Córdoba in 1236 and Sevilla in 1248, a sedentary, farming, pottery-making people was settling the banks of the Pecos. This cultural and human migration came mainly from the area of the San Juan drainage. It seems also to have absorbed increments from the plains to the east. Geographically, the upper Pecos lay between; culturally, it owed more to pueblos than to plains.

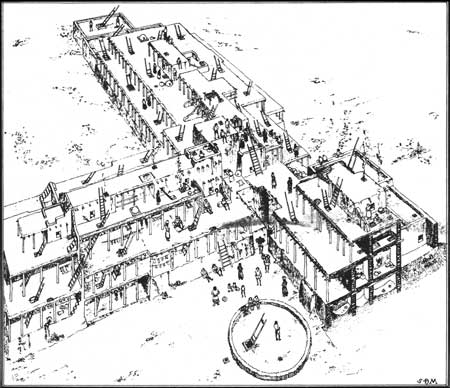

The immigrants had lived at first in haphazard collections of rectangular rooms built mostly of coursed adobe mud, easily added to or abandoned as need arose, sometimes more or less linear, sometimes enclosing small patios, "straggling affairs on flat land open to attack from any direction, sites chosen with no eye to defense." One such town, known to archaeologists as the Forked Lightning Ruin, lay on the west bank of the Arroyo del Pueblo, or Galisteo Creek, just half a mile below the site of the future Cicuye and a little over a mile above the arroyo's confluence with the Pecos. Its time of maximum occupancy, during which it must have housed hundreds of people, had run from about 1225 A.D. to 1300, when nomads from the plains, or other Pueblos, began sporadic raiding. Forced for the first time to think in terms of defense, the people of Forked Lightning had made an orderly exodus up the arroyo and crossed over to where a steep-sided, flat-topped ridge afforded them an unobstructed view all round. To the north loomed the great gray-green mountains in whose ponderosa fastness the river rose. Clear and cold but shallow, really no more than "a small perennial stream," it flowed by their ridge a mile to the east. The valley here, four or five miles wide, was contained toward the sunrise by the gentler foothills of the Tecolote Range and toward the sunset by the towering reddish cliffs of Glorieta Mesa. Here, too, scattered piñon and juniper trees, chamisa bushes and cholla cactus gave way to open spaces of tall native grasses. If one followed the river southeastward around the end of the Tecolote foothills, he soon looked out upon the ocean-like expanse of the true plains.

For about a century and a half, from roughly 1300 to 1450, generations of the Forked Lightning people and others who joined them on their long narrow ridge, or mesilla (literally, little mesa), had moved about from one spot to another, building new clusters of one-storied dwellings rather than repairing the old ones. Because there was an abundance of sandstone at hand, they had become masons, laying up walls of "stones embedded between cushions of mud." Curiously, their earliest work was their best. Examining examples of later buildings, pioneer archaeologist Adolph Bandelier concluded that it was no better than "judicious piling," and sometimes worse. Presumably because of pressure from enemies, everyone in the valley had gathered on the mesilla by about 1400. Around 1450, a year before Isabella of Castile was born in Spain, they had begun a monumental community project. Designed in advance and built as a unit, a single, defensible, multi-storied apartment building, it took the form of a giant rectangle around a spacious plaza. In all, it covered about two acres at the mesilla's north end. This was the fortress-pueblo of Cicuye, or Pecos. Factionalism at Cicuye

By the time the Spaniards appeared, Cicuye, with a population of two thousand or more, stood alone as the easternmost of the Pueblo city states. Although its people shared the Towa language with the Jémez pueblos sixty miles to the west, they were in no binding way allied with them. In fact, to the Spaniards' bewilderment, each of the one hundred or so native communities that qualified as pueblos in l540, whose citizens spoke eight or more mutually unintelligible languages, was a politically autonomous unit. Alliances for the most part were unstable and shifting. Still, Cicuye commanded respect. Among the largest and most powerful of the city states, it enjoyed by 1540 the benefits of a well-developed commerce between pueblos and plains. Inside Cicuye's protective walls of stone and earth, however, in the midst of prosperity, the seeds of factionalism may already have taken root. Living together in such close quarters, the Pueblos had long striven for conformity of behavior. Passive assent to the group will, suppression of individualism, and the pursuit of uniformity in all things characterized Pueblo tradition. There was no place in the rigidly controlled Pueblo community for the boastful self-assertiveness esteemed among some plains tribes. Yet at Cicuye, gateway to the plains, the danger of such "contamination" ran high. Plains Indians came regularly to trade at Cicuye. Slaves from the plains lived in the pueblo. And certain men of Cicuye, it would seem, in the interest of diplomacy and trade had become virtual plainsmen themselves, men like Bigotes. [11] Reception of Spaniards They all came out that day to gawk and to receive the Spaniards. "With drums and flageolets similar to fifes, of which they have many," they escorted their visitors into the pueblo. The mood was one of guarded festivity. As an offering, the Indians laid before Álvarado and his men quantities of native dry goods—cotton cloth, feather robes, and animal skins. They held out objects made of turquoise mined locally. As intently as any fortune seeker, Father Padilla studied these natives for just one ornament of gold, for some indication of trade with the rich Seven Cities he sought so passionately, But they wore none. Their beads and pendants were of turquoise, shell, and non-precious stones. They prized eagle claws and grizzly bear teeth. Flageolets, whistles, and rasps they fashioned from bone, and jingles from shell. Despite his disappointment, the friar must have proceeded as in the other pueblos. [12]

Ever since the first twelve Franciscan apostles of New Spain had erected a great cross at Tlatelolco in 1524, members of the Order had been setting up crosses in Indian communities wherever they went. Father Padilla reported to Coronado from Tiguex that they had put up large crosses in the pueblos along the Río de Nuestra Señora. And they had "taught the natives to venerate them." Watching the Indians sprinkle sacred corn meal and tie prayer plumes to the crosses, the Spaniards assumed that they were venerating them. "They did it with such eagerness," Father Padilla observed,

Reading the Requerimiento At some point during the festivities, Álvarado was obliged to explain to assembled Cicuye what it meant to be vassals of the Spanish crown. Almost certainly he had the requerimiento read to them, as he had ordered it read to the Hopis. This remarkable manifesto, which had accompanied all Spanish conquerors in America since 1514, related how God the creator and lord of mankind had delegated His authority on earth to the Pope, "as if to say Admirable Great Father and Governor of men," and the Pope in turn had donated the Americas to Their Catholic Majesties, the kings of Spain. Therefore, Cicuye must acknowledge the sovereignty of "the Church as the ruler and superior of the whole world," the Pope, and in his name, Charles, king of Spain. They must also consent to have the Holy Catholic Faith preached to them. They would not be compelled to turn Christian unless they themselves, "when informed of the truth, should wish to be converted." If they did, there would be privileges, exemptions, and other benefits. But should they refuse, the requerimiento continued, "we shall forcefully enter into your country and shall make war against you in all ways and manners that we can, and shall subject you to the yoke and obedience of the Church and of their highnesses." Their wives and children would be sold into slavery, their goods confiscated, and their disobedience punished with all the damage the Spaniards could inflict. "And we protest that the deaths and losses which shall accrue from this are your fault, and not that of their highnesses, or ours, or of these soldiers who come with us." [14] If they understood any of it, which is unlikely, the people of Cicuye did not object, not initially. The invaders stayed several days, camped outside nearby. One of them, after a look around, reported that the pueblo had "eight large patios each one with its own corridor." He must have been referring to patios on the upper levels of the house blocks, not to the great central plaza. [15] Even though made of rough sandstone and mud, some of the houses struck him as tolerably good. For the characteristic underground rooms they found in the pueblos, the Spaniards used the descriptive word estufa, in Spanish a heating stove, and by extension, an enclosed heated room for sweat baths. They assumed that these warm estufas with their fire pits served as quarters for the unmarried lads of the pueblo and as council rooms for the men, as baths in the Roman sense, On first contact, the invaders missed the kivas' religious function.

The People of Cicuye The inhabitants of Cicuye, in the Spaniards' eyes, were no different from those of Tiguex. They looked the same. They showed the same respect for their old men, practiced the same division of labor between men and women, and raised the same crops—maize, beans, and squash—except for cotton and turkeys which they obtained in trade. They dressed the same, made similar pottery, and observed many of the same customs. As in the other pueblos, the Cicuye maidens, Castañeda noted later, "go naked until they take a husband, because the people say that if they do wrong it will soon be seen and therefore they will not do it." [16] Álvarado and Father Padilla pressed their hosts about what lay to the east. The Indians obliged with two guides, captives from "the kingdom of Quivira" on the eastern plains. Because one of them looked to the Spaniards like a Turk, they called him El Turco. The other, known as Sopete, was the same lad who had sported the buffalo painting on his body. Despite language barriers, El Turco proved extremely apt at communicating. He soon grasped what the invaders were after.

With the loan of El Turco and Sopete, the Spanish column sallied forth from Cicuye. "After four days' march from this pueblo they came upon a land flat like the sea. On these plains," wrote an eyewitness, "is such a multitude of cattle that they are without number." Álvarado had discovered the buffalo plains. After his men had enjoyed some sport jousting with the beasts, the captain ordered an about-face. He had something more important than buffalo to report to his general. El Turco's Tales of Quivira El Turco, it seemed, under Father Padilla's withering questioning, had indicated by signs and a smattering of Nahuatl that Quivira, some days to the northeast, abounded in gold, silver, and rich textiles. This at last must be the Seven Cities. Furthermore, alleged El Turco, Bigotes of Cicuye could confirm it. Bigotes had in his possession a golden bracelet that had belonged to El Turco. Back at Cicuye, the anxious Alvarado confronted Bigotes and the elderly headman the Spaniards called Cacique. They denied that any such precious bracelet ever existed. When the two natives refused to go with him to see Coronado, the Spanish captain succeeded in getting them to his tent. There he had them put in collars and chains along with El Turco. That was too much for the people of the pueblo. "They came out to do battle, shooting arrows and reviling Hernando de Alvarado, saying that he was a man who broke his word and betrayed their friendship." Either they feared for the lives of the hostages and were trying only to bluff the invaders, or the pueblo with "as many as five hundred warriors" was badly divided, for the men of Cicuye inflicted no casualties. The events of the next few days are jumbled in the accounts of the expedition. El Turco "escaped" twice. Both times Álvarado let Bigotes and Cacique go to retrieve him. Then, while relations between Spaniards and Cicuye seemed badly strained, the Spanish captain and his men purportedly joined forces with three hundred of the pueblo's warriors for a campaign against a people called Nanapagua. A few days later, the campaign was dropped and the Spaniards withdrew to rejoin Coronado, taking with them Cacique, Bigotes, El Turco, and Sopete collared and chained. [17] The first meeting of the invaders and Cicuye had ended in bad faith. Álvarado Takes Captives to Tiguex Snow had already fallen when Hernando de Alvarado reached the Tiguex pueblos with his prisoners. There he found García López de Cárdenas and an advanced detail setting up camp for the entire army. The invaders would winter among the Southern Tiwas as Álvarado and Fray Juan de Padilla had suggested, an experience none of them would ever forget. The night after Coronado arrived, Captain Álvarado reported to him with El Turco in tow. The Indian captive cooperated fully. What he related delighted the general. Across the plains to the east, he gestured,

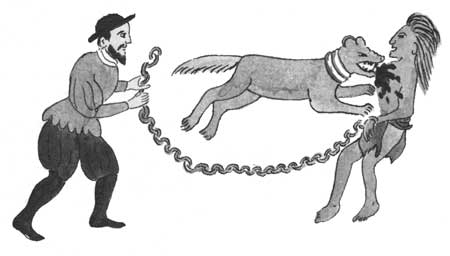

Visions of Riches to the East El Turco was probably describing the Mississippi where some rulers did indeed travel in ornate ceremonial barges and the garfish grew as long as horses. Father Padilla could see it all, and more. This heathen plainly had glimpsed the marvels of Antillia. To Coronado and his wearied adventurers, lodged in earth houses, El Turco's mirage must have sounded like another Mexico. But before they could see it themselves, they had to endure the pains of winter and a war against the people of Tiguex. The invaders had simply taken over one entire pueblo, just above present-day Bernalillo. The natives had moved out grudgingly, seeking in other pueblos shelter from the biting cold. At first the Spaniards traded petty merchandise for blankets, turkeys, and maize, as the viceroy had ordered; then in dire need they resorted to forced levies. A soldier raped an Indian woman. Trying to get at the truth of the golden bracelet, someone sicced a dog on Bigotes. Even so, neither Captain Álvarado nor Father Padilla could shake the Indian's plea that El Turco was lying. The rankled Tiwas began by stealing and killing Spanish horses. When Coronado sent captains to reprimand them, they holed up in their pueblos and shouted abuse. The invaders had no choice. They could not hope to set out for the golden land to the east with defiant Indians at their rear. Therefore the general, with the necessary if reluctant consent of the friars, resolved to wage the kind of war spelled out in the requerimiento. If the Indians refused to submit, he would show them no quarter. They refused.

The Sieges of Arenal and Moho The first assault aborted. Inside the pueblo, called Arenal by the Spaniards, the defenders held out. Not until the attackers knocked holes in the walls and lighted smudge fires did the battle turn. Then as the choking Tiwas poured out, the Spaniards cut them down or burned them at the stake. As an object lesson, Cacique and Bigotes, leaders from the powerful Cicuye, along with El Turco and Sopete, were made to watch the Tiwas burn. The extreme penalty inflicted upon Arenal did not end the war. Fortifying several other pueblos, the unyielding Indians forced the Spaniards to maintain long winter sieges. As attack after attack failed, months passed. From early January to late March 1541, the defenders of a pueblo called Moho repulsed every onslaught and every appeal to surrender. When finally thirst forced them to flee one night in the dark, the invaders on horseback rode them down or took them captive. Another pueblo fell and was sacked. Dozens of Tiwa women and children found themselves slaves in the camp of the Spaniards, just as the requerimiento had warned. [19] The Pueblos Divided Coronado's rude thrust into the heartland of the pueblos upset the prevailing balance of power. While besieged Southern Tiwas fought for their lives, the Keres pueblo of Zia provided the invaders with blankets and food stuffs and an offer of alliance. The Tiwas appealed to Cicuye, a pueblo with reason enough of its own to oppose the Spaniards. If the eastern stronghold did send aid, it went unrecorded. On the contrary, claimed Coronado, the captives Cacique and Bigotes told him that Cicuye and the Tiwas were enemies. If the Spaniards would give them one of the Tiwa pueblos as spoils to settle and farm, the men of Cicuye would "come and help him in the war." Whether or not the two Indians really made that offer, and whatever their intent, Coronado knew that he must make his peace with their pueblo, the gateway to the east.

By all accounts, Cicuye was a power to be reckoned with. "Feared throughout that land," the eastern pueblo, because of its very location, had to maintain relations with people of both plains and pueblos. About l525, according to Pedro de Castañeda, the fierce Teyas had tried to conquer Cicuye. This plains people, likely Caddoan-speaking ancestors or relatives of the Wichita Indians, allegedly had destroyed some pueblos in the Galisteo Basin so thoroughly that Castañeda thought the attackers must have used war machines. They had assaulted Cicuye but failed to carry it. Now, in 1541, the Teyas were at peace with the Pueblos. "Although they receive them as friends and trade with them, at night the visitors do not stay in the pueblos but outside under the eaves." [20] Evidently the strength Cicuye had shown against the Teyas had brought the Tano pueblos of the Galisteo Basin under her sway. "There are along this road," wrote Castañeda, "toward the snowy mountains seven pueblos—one of them half destroyed by the above-mentioned people—which are under obedience to Cicuye." Coronado Seeks Aid of Cicuye Sometime during the course of the Tiguex war, Coronado resolved to go in person to cement an alliance with Cicuye. To show his good will, he released Cacique and escorted him home. Bigotes, "ill disposed and somewhat dishonest in his conduct," he refused to return just yet. Approaching the tiered gray-brown citadel, the personal emissary of the emperor's viceroy must have awed the natives in his suit of golden armor and his plumed helmet from which the dents of Zuñi had been hammered out. This was an occasion of state.

En Route to Quivira In late April or early May 1541, the residents of Cicuye looked out to see Coronado's entire army encamped in the valley below: more than fifteen hundred persons counting Mexican Indian allies and Tiwa slaves, likely an exaggeration, with hundreds of horses, cattle, and sheep. Behind them the pueblos of Tiguex lay deserted. The general, against the counsel of some of his officers, had committed his whole force to the discovery of Quivira. As incentive, El Turco had embellished his description to the point "that had it been true, it would have to have been the richest thing in the Indies." [22] Cicuye now "rejoiced" at the restoration of Bigotes and the thought of the invaders' imminent departure for the plains. The inhabitants shared their provisions. Cacique and Bigotes gave Coronado another Quivira guide, a young lad named Xabe, who like Sopete agreed that gold and silver were to be found in his land but not in the abundance El Turco had implied. "The army set out from Cicuye," observed Castañeda, "leaving the pueblo at peace and to all appearances content and bound to maintain friendship because their governor and captain had been restored to them." Later, hundreds of miles to the northeast, El Turco would implicate Cicuye in a plot to destroy the invaders. [23]

Much as the Pueblo Indians might have wished it, the plains did not swallow up the Spaniards. Four days out the army built a bridge not far from today's Conchas Lake and crossed over the Canadian River. [24] Led on by El Turco, they came upon the buffalo, so numerous, said Coronado, that "there was not a single day until my return that I lost sight of them." They met and marveled at the Apaches called Querechos, with their portable skin tipis and dog travois, following the great dark herds. Some days southeast over the hauntingly flat Llano Estacado, the Spanish caravan encountered the people called Teyas. Although these tattooed and painted natives closely resembled the Querechos in appearance and style of life, at least while on the hunt, the two groups were enemies. The Teyas led the Spaniards down into a deep gorge. What they conveyed to Coronado, the abrupt change in terrain, and the expedition's southerly instead of northeasterly route finally convinced the general that El Turco was purposely leading them astray. Ordering the bulk of the army back to Tiguex, Coronado with thirty of his best mounted men, a dozen or so servants and the pigheaded Fray Juan de Padilla struck north "by the needle" for Quivira about June 1, 1541. Sopete led the way. El Turco followed in chains. The Murder of El Turco By mid-summer the invaders beheld Quivira. They were in present-day Kansas, centuries before the first plow. The countryside appeared gloriously rich and verdant. The rivers and streams ran clear. But instead of the alabaster walls of Antillia or even a tree hung with golden bells that played in the breeze, there were only scattered settlements of grass lodges and one old chief with a copper ornament. The people of Quivira were the semisedentary Wichitas living along the great bend of the Arkansas River. [25] Several weeks of exploration failed to turn up anything but stories of wonders farther on. A council of officers agreed with the general: they should turn back to Tiguex and next year marshal a larger force to explore beyond Quivira. Nothing could shake Father Padilla's belief that the Seven Cities rose farther east, ever farther. El Turco had become a liability. Because of his alleged scheming with the natives of Quivira, the Spaniards decided to eliminate him. Under interrogation he laid bare the plot of Cicuye as well. Why, the Spaniards demanded, had he lied and so maliciously misguided them? He answered

Melchior Pérez, one of Cicuye's discoverers, "from behind put a rope around El Turco's neck, twisted it with a garrote, and choked him to death." [27] Burying the body at night, the Spaniards broke camp in haste and rode west by a more direct route to rejoin the army at Tiguex. Coronado feared what Cicuye might already have done. Cicuye Defies the Invaders

By their actions, the people of the eastern fortress-pueblo confirmed El Turco's story. When Capt. Tristán de Arellano, in command of the main army returning from the plains, had approached Cicuye, he found the pueblo hostile. The inhabitants retired inside their walls, pulled up their ladders, and offered no provisions to the Spaniards. The Tano pueblos, evidently prompted by Cicuye, did the same. The natives at Tiguex, who had reoccupied some of their pueblos, fled again, and the invaders moved back in. Late that summer of 1541, Arellano, a relative of the viceroy, took forty men and went back to Cicuye to meet Coronado. He sensed that the general and his party might be marching unawares into an ambush, which is precisely what the warriors of Cicuye had in mind. Confident that they could deal with Arellano's force first, they poured out of their fortress to do battle. But the Spaniards, some wielding sword and lance from horseback, others with feet firmly planted firing their smoke and lead-belching arquebuses, turned the Indians back. Early in the fight two of Cicuye's most touted warriors fell dead. After that, said Castañeda, the Indians refused to come out in the open, retiring instead to the refuge of their stone pueblo. The Spaniards kept up the battle for four days "to inflict some punishment on them, as was done, considering that they killed some of their people with cannon fired at the pueblo." These casualties, the first ones recorded at Cicuye by the invaders, seemed to take the fight out of the pueblo. To make certain they did not assault Coronado, Captain Arellano camped nearby until the general arrived, sometime in mid-September. News of what had happened at Cicuye saddened Coronado, just as the Tiguex war and the execution of El Turco had saddened him, He knew that sooner or later he would be obliged to justify each and every Indian death before the authorities of New Spain. He had discovered nothing to make the judges forget their duty. Before he rode on to Tiguex, the general reportedly calmed Cicuye, "leaving the pueblo more settled, for presently the people came out in peace and spoke with him." [28] Father Padilla Persists in the Quest Talk of going back to explore beyond Quivira persisted in the Spanish camp at Tiguex all through the winter, even after the general suffered an apparent concussion in a fall from his galloping horse. Fray Juan de Padilla would not let it drop. He had vowed to return to Quivira, and return he would. He even claimed to have permission from his superior, Father Provincial Marcos de Niza, though it is doubtful that Niza would have let him go back virtually alone. By early spring the mood of the majority was against the Franciscan. Most of the army wanted to abandon the quest and go home. The melancholy, shaken Coronado, easily swayed now by disenchanted officers, would hear of nothing but New Spain. He forbade any of the soldiers to remain behind with Father Padilla. If the other friars wanted to stay, he would not prevent it. That was their business. Padilla did stay, and not entirely alone. A simple and prayerful old lay brother, Fray Luis de Úbeda, chose to end his days among the Pueblos rather than face the walk back to New Spain. Lucas and Sebastián, Tarascan Indian catechists and helpers trained by Father Padilla in his former convento of Zapotlán, would accompany their master wherever he wanted to go. They were donados, native lads "donated" to the friars, dressed in knee-length gray tunics and girded with the knotted cord of the Franciscans. In addition, Padilla talked Coronado into allowing him the services of a Portuguese soldier, one Andrés do Campo. Here was an interpreter for the Portuguese-speaking court of the Seven Cities. Several more servants and the half-dozen natives of Quivira who had guided the general back across the plains completed the roster of those left behind. The Death of Padilla Coronado provided them with supplies and a mounted escort to Cicuye. Brother Luis intended to remain there while Father Padilla pursued his vision of the Seven Cities. Very soon, Padilla, Campo, Lucas and Sebestián, a black and a mestizo, along with the Quivira guides, sheep, mules, one horse, religious paraphernalia, and gifts, set out eastward, never to be seen in Cicuye again. The obsessed friar did reach the cross he had erected in Quivira the year before. A short way beyond, Indians killed him. The Portuguese, after nearly a year's captivity, escaped south to New Spain with news of Padilla's violent end. Lucas and Sebastián too trekked back by another route. [29] After sending to Cicuye another flock of sheep for Brother Luis, Coronado gave the order for the army to move out from Tiguex. They had forsaken their conquests. It was April 1542. Almost as suddenly as they had come, the invaders had gone.

The Spaniards Depart At Cicuye only the bitterness remained. The Spaniards had come in peace and provoked war. They had held certain of the pueblo's leaders captive, and they had killed some of its people in battle. Yet nothing they had done, nothing they had brought, vitally effected life at Cicuye once they were gone. Their gifts—the beads, the glass and metal trinkets, the ribbons—wrought no revolutions among the people of Cicuye. Their sheep did not survive. The reading of the requerimiento and the symbolic planting of the cross meant nothing after Coronado and his army had vanished in the direction from which they had come. If the invaders had aggravated a rift among the people of Cicuye—revealed perhaps in the pueblo's alternate "friendliness" and hostility—it did not drive them apart. Subsequent expeditions found them still living together in the closeness of their one fortress-pueblo. A Missionary Left Behind at Cicuye As for the aged Brother Luis de Úbeda, the first Christian missionary to the people of Cicuye, neither he nor the trials of his humble ministry moved them to make room in their hearts for a poor man nailed to a cross or His Blessed Mother. Describing his aspirations to Capt. Juan Jaramillo, the friar had said

Much respected by Coronado's soldiers because he embraced poverty so completely and prayed continually, qualities they expected in a Franciscan, Fray Luis had come from Spain with the returning Bishop Zumárraga in 1533 and had served in the famous prelate's household, He was an artless soul, anything but an intellectual. Because he spent so much of his time in prayer, he preferred to be alone. Still, no matter how unobtrusive and gentle he was, apparently the people of Cicuye did not want him around. The last bit of reliable evidence about him, as recorded by Castañeda, leaves his fate in doubt.

The details of Brother Luis's "ministry" at Cicuye supplied by the mid-seventeenth-century Franciscan chronicler Fray Antonio Tello may have some basis in fact or they may be pure fancy. According to Tello, the Indians promised the departing Spaniards that they would treat the old friar kindly. They gave him a tiny room and board. After Coronado's men last saw him being led away, Brother Luis returned to Cicuye, or so the story goes. Every morning the natives would bring him a portion of "atole and tortillas" without saying a word. As the scowling old men passed by, the friar would salute them, "May God convert you!" [32] Whatever happened to Brother Luis, there is no reason to believe that anyone at Cicuye wanted to learn more about the Christian faith. It was as if the invaders had never come.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||