Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Men of Wealth and Power Like Carolingian kings, attended by swarms of family, servants, and hangers-on, the rich and powerful moguls of New Spain's northern marches held court in their fortified adobe castles, dispensed justice like patriarchs, and welcomed travelers with prodigal hospitality. Because these hombres ricos y poderosos colonized, governed, and sustained vast reaches of the silver-rich north at their own expense, the king granted them notable, almost feudal independence. Not that he ever intended it to last. Always royal lawyers hovered about, eager to retract the privileges of an adelantado who defaulted. For their part, the frontier ricos kept agents at court, married their daughters to royal judges, and applied bribes and favors where they would do the most good.

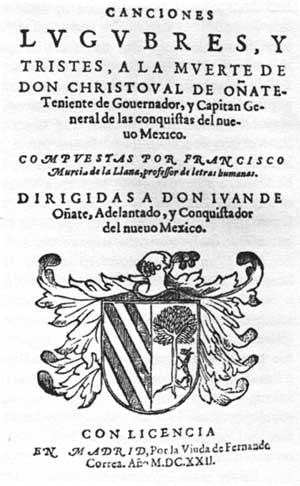

Juan Bautista de Lomas y Colmenares, master of Nieves north of Zacatecas, epitomized the feudal mentality of the northern barons. In 1589, one year before the Castaño de Sosa fiasco, don Juan Bautista had signed a contract for the pacification of New Mexico with Viceroy Marqués de Villamanrique, whose secretary happened to be Lomas' son-in-law. Not only did Lomas ask for the esteemed feudal title adelantado for his family in perpetuity, the office and authority of governor and captain general for six heirs in succession, and the noble rank of count or marques, but also, among other things, forty thousand vassals in perpetuity and a private reserve of twenty-four square leagues, or 120,000 acres! That was too much. Philip II did not want New Mexico that badly. Next, Viceroy Luis de Velasco entered into a contract with Francisco de Urdiñola, Lomas' archenemy. Its terms were more in keeping with the 1573 colonization laws, and for a time it appeared that the crown would accept Urdiñola's offer. Meanwhile Lomas fumed. By intrigue and influence, the lord of Nieves spun so tight a web of litigation, including the charge that Urdiñola had poisoned his wife, that his rival could not move. Velasco looked for another candidate. [1] For some time the viceroy had discussed the pacification of New Mexico with don Juan de Oñate y Salazar, a member of his intimate circle, a man whose "age, fortune, and talents" well qualified him to undertake the venture. Evidently this gentleman had excused himself previously from consideration because of his ailing wife. When she died, he found him self "free to negotiate." In September of 1595, Velasco signed a contract with him. The viceroy could hardly have done better.

Forty-seven years old, experienced in frontier affairs, and rich, Juan de Oñate had been born with a Zacatecas silver spoon in his mouth. His Basque, conquistador father Cristóbal de Oñate and father-in-law Juan de Tolosa were half of the Zacatecas big four. Through his recently deceased wife, Isabel Cortés Moctezuma, don Juan could claim both the conqueror of Mexico and the Aztec emperors as relatives. "From the time he was old enough to bear arms" he had fought Chichimecas and developed mines. Now, for stakes he deemed high enough, Juan de Oñate would gamble his fortune on the chance that he could make New Mexico pay. [2] Velasco had already accepted Oñate's offer to arrest and bring back from New Mexico another party of illegal entrants. One Capt. Francisco Leyva de Bonilla, commissioned by the governor of Nueva Vizcaya to punish some cattle-thieving Indians east of Santa Bárbara, had thrown off the governor's aurthority and made for New Mexico. There was no telling what harm "such unrestrained and audacious men would cause the inhabitants of those provinces." Therefore on October 21, 1595, when Velasco in the name of Philip II appointed Oñate "governor, captain general, caudillo, discoverer, and pacifier" of New Mexico, he charged him with a twofold mission: proceed against the traitor Leyva and pacify the land. [3]

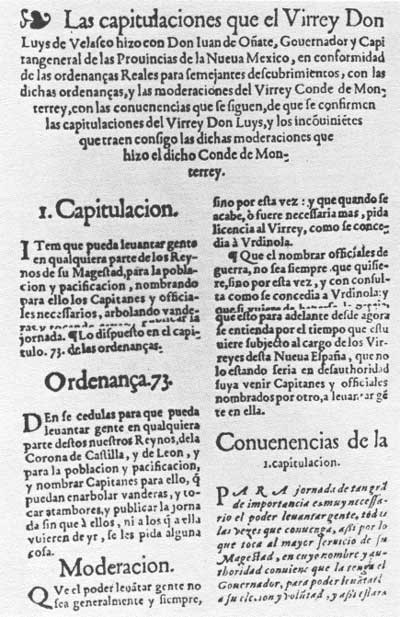

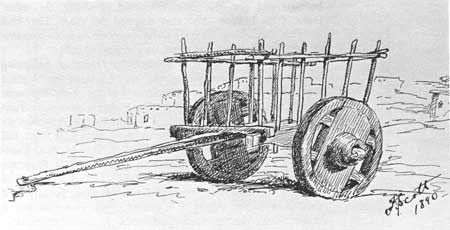

Under the contract, Oñate committed himself to provision and take to New Mexico at least two hundred men and to supply thousands of head of stock, tools, and necessities, twenty carts, and a large personal outfit. All of this he hoped to have assembled at Santa Bárbara by March of 1596. Besides the governorship for two lifetimes, with all the many powers that went with it, don Juan was to receive the title adelantado as soon as he took possession. He was to govern independently of the viceroy, answering instead directly to the Council of the Indies in Spain. Velasco had been scrupulous in adhering to the 1573 ordinances. Where Oñate had bid too high, the viceroy cut him down—Oñate requested his offices for four lives but Velasco confirmed them for two. Oñate asked for a loan of twenty thousand pesos while Velasco authorized six thousand. Oñate bid for an annual salary of eight thousand ducats and Velasco countered with six. Even as recruiting lists were opened amid pageantry at the viceregal palace and to the beating of drums in Puebla, Zacatecas, and elsewhere, a new viceroy entered Mexico City. Luis de Velasco, Oñate's friend and patron, had been promoted to Peru. Instead of speeding don Juan on his way, as he might have done, the outgoing executive insisted that his successor study the contract and satisfy himself that all was in order. That cost Oñate two years. The Count of Monterrey listened to Oñate's detractors as well as to his friends. The New Mexico grantee was not really so rich. His father had badly mismanaged the estate. There were debts. Even if relatives and friends contributed, Juan de Oñate would be hard pressed. Carefully, the new viceroy studied the contract, along with copies of the Lomas and Urdiñola documents. He then proceeded to strike or significantly limit at least seven major concessions to Oñate. The one that most offended him was the New Mexico governor's independence of the viceroy and audiencias of New Spain. If aggrieved Spaniards and Indians in New Mexico could appeal only to Spain, reasoned Monterrey, Oñate's authority would be virtually unchecked. Besides, some concessions should be withheld until don Juan proved himself. The king could always reward him and his people later for a job well done. [4] Colonization Delayed Grudgingly, Oñate's agents accepted the changes. By late summer 1596, the governor had the bulk of the expedition on the road north from Zacatecas. Just as he was about to cross the difficult Río de las Nazas, a viceregal inspector, don Lope de Ulloa, overtook the lumbering train. He carried an urgent secret message. The king had suspended the expedition. Don Juan was to hold up the entire operation until further word from Spain. Stung by the unreasonableness of the order, Juan de Oñate did the only thing he could, he "took the royal cedula [decree] in his hands, kissed it, placed it on his head, and rendered obedience with due respect." Then he protested. Such a delay, if prolonged, could ruin him and others who had mortgaged all but their souls to join the venture. Hungry colonists would consume the provisions on the spot. They would disband overnight if they ever found out why the expedition had halted at the mines of Casco ten days short of Santa Bárbara. To prove that he had more than fulfilled his contract, as well as to reassure his impatient following, Oñate requested Ulloa to carry on with "the inspection, review, and inventory of the people, provisions, munitions, equipment, and other things he is taking." The livestock and stores already collected in the Santa Bárbara area could be tallied there and added to the inventory. When finally the count and appraisal of everything from laxative pills and horseshoe nails to jerked beef and colonist families was completed in February 1597, it was found that Oñate had indeed surpassed the requirements of the contract. Still he had to wait. [5] By casting doubt upon the financial capability of Oñate, the Count of Monterrey had opened the door to a rival pretender, don Pedro Ponce de León, wealthy Spaniard of Bail&te;eacun. Ponce proposed a contract to the Council of the Indies more favorable to the crown in every regard. For over a year Philip II played off the two contenders one against the other. Meanwhile Monterrey had taken up Oñate's cause, probably for no small consideration. Ponce's health and finances worsened. In the spring of 1597, the king, while keeping Ponce on the string, secretly instructed Monterrey to find out if Oñate was still in a position to proceed. If so, he was to be given the royal blessing. [6] A second inspection of the Oñate expedition, finally pulled back together again by December 1597 and encamped in the Santa Bárbara district, lasted more than a month. This time only 129 men passed muster, 71 short of the two hundred Oñate had agreed to take. When a cousin of means gave bond for another eighty soldiers and for shortages of equipment and provisions, the last obstacle fell away. The inspector took his leave at the Río Conchos. Some twenty-five miles farther on, the caravan halted for a month while an advance party scouted ahead and the Franciscans caught up. Then in March 1598—two years behind schedule—the colonizing expedition of Juan de Oñate moved out. [7]

Oñate's Friars It was no coincidence that Franciscans accompanied Oñate. Viceroy Velasco's ill-advised suggestion that members of all the religious orders, especially the Jesuits, should join in the spiritual conquest of New Mexico ran counter to more than half a century of tradition. [8] First on the scene in New Spain, the friars of St. Francis, beginning in 1524, had pre-empted whatever areas they chose—in the environs of Mexico City and Puebla, in the present states of Hidalgo, Morelos, and Michoacán, and in the vastness of Nueva Galicia and the Gran Chichimeca. The Dominicans who disembarked in 1526 found themselves already limited geographically by Franciscans. When the Augustinians arrived in 1533, they had to fit their apostolate into spaces left by the other two orders. Although the majority of Franciscans preferred to minister to the sedentary natives of central Mexico, other more venturesome grayfriars, explorers, military chaplains, and itinerant missionaries to the Chichimecas, laid their Order's claim to the north. Not until the last years of the sixteenth century did the energetic new Society of Jesus gain a foothold in the Sierra Madre Occidental and begin building a triumphal northwest missionary empire. Even then, the great arc stretching from Tampico on the Gulf of Mexico west to the foothills of the Sierra remained a Franciscan monopoly. As early as July 1524, seventeen sons of St. Francis had met in chapter in or near the Mexican capital and organized themselves as a proper "custody," or dependent administrative district, of the Spanish Franciscan province of San Gabriel de Estremadura. As the Custodia del Santo Evangelio, they elected one of their number custos, superior for a triennium, and designated four towns as sites for Franciscan houses, known as conventos, with Mexico City as headquarters. At each house, a designated friar acted as local superior, or guardian. Several members, called individually definitors, and collectively the definitory, made up a council to advise the Father Custos. So rapidly did the Franciscan ministry grow in Mexico that the order raised the custody of the Holy Gospel to full provincial status in 1535. The following year at their fourth triennial chapter, the members elected a Minister Provincial.

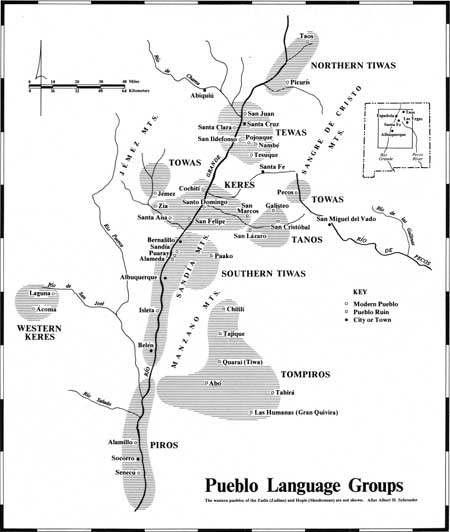

To the west and north in Michoacán-Jalisco, where the mother province of the Holy Gospel set out one of several custodies, the process repeated itself. In 1565, that custody came of age as an autonomous province, later splitting in two as the province of San Pedro y San Pablo de Michoacán and the province of Santiago de Jalisco. A 1573 shipment of twenty-three friars from Spain made possible the founding of the custody of San Francisco de Zacatecas in Chichimeca country. Despite the proliferation of custodies and provinces, Holy Gospel retained its primacy as the original Mexican province. Its principal house, which came to be called the convento grande, regularly served as the residence of the Franciscan commissary general of New Spain, overseer of the Order's entire Central and North American theater. [9] Oñate's contract called for six Franciscans, five of them priests and one a lay brother. As provided in the 1573 ordinances, they were to be outfitted for the expedition at the crown's expense. Early in 1596, the Holy Gospel province made the appointments, at the same time requesting through the commissary general of New Spain that the number be doubled.

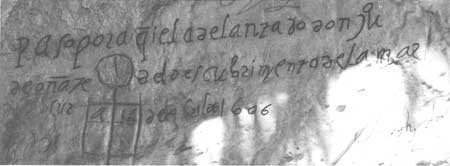

Friars versus Bishops Just as the chosen six were about to set out "in keeping with Your Majesty's instructions that for the present only friars of this Order be sent," the bishop of Guadalajara hurled an unsuccessful challenge at them. Brandishing his episcopal dignity, he avowed that churches established in New Mexico "must belong to his diocese." At base this was more than another round in the unending jurisdictional feud between Guadalajara and Mexico. It was a typical confrontation between the secular, or diocesan, clergy of bishops and parish priests on the one hand and the regular clergy, or religious orders, on the other. Because of the immensity of converting and ministering to the New World, the popes had granted members of the religious orders authority to administer the sacraments, not only to their native converts but to the faithful as well. When the Council of Trent in principle returned the faithful to the exclusive care of the parish priest, Pius V restated the friars' right to administer the sacraments to all in the absence of a secular, even without the bishop's authorization. Extremely jealous of their privileges, the regular clergy on occasion tried to throw off the bishops' authority entirely. The bishop of Guadalajara's bid to assert his jurisdiction in New Mexico before the Franciscans entrenched themselves was only the beginning. For two and a half centuries, Mexican bishops would claim authority over the distant colony, and for at least half that long, the Franciscans would defy them. [10] Viceroy Monterrey had no intention of permiting shared jurisdiction in New Mexico. "This might give rise to dissension and clashes between friars and secular priests." While he awaited the confirmation of theologians and the audiencia, another dispute broke over the friars assigned to join Oñate. Without the viceroy's knowledge, one of them carried with him authority from the Inquisition to act as its agent on the expedition and in New Mexico. Almost immediately someone objected. The friar was a criollo, a Spaniard born in New Spain, as well as intimate friend of Oñate, "for which reasons he might in some way cover up whatever excesses don Juan and his people might commit." If, wielding the power of the Inquisition, he sided with Oñate against his superior and the other friars, he could retard missionary work among the Indians and scandalously split the church in the new colony. When the Holy Office refused to rescind the friar's commission, Monterrey prevailed upon the Franciscan commissary general to recall him. Not until the mid-1620s did the Inquisition formally extend its influence to New Mexico. [11] Oñate En Route At final count, Oñate's band of Franciscans numbered ten two short of the apostolic twelve requested. Led by Comisario fray Alonso Martínez, their superior in the field, they and their escort caught up with the expedition on March 3, 1598, while it was encamped near the Conchos. One venerable religious, later identified as don Juan's confessor, had been with the enterprise from the start, through all the delays and frustrations. He was the almost seventy-year-old Fray Francisco de San Miguel, "a saintly old barefooted and naked-poor friar." Eight of the ten were priests and two were lay brothers. Three Mexican Indian donados attended them. When the scouting party reported back, the whole train pointed north, stringing out in a narrow, dusty procession, miles long. Unlike previous entradas, which had detoured eastward down the Conchos, Oñate struck almost due north across the trackless Chihuahua desert. That way he gained the Río del Norte just south of present-day Ciudad Juárez. On its banks, the entire company from captains to oxherds assembled to see the resplendent adelantado take formal possession of New Mexico. It was Ascension Day, April 30. Personally nailing a cross to a living tree in the name of the Holy Trinity, the Blessed Mary, and St. Francis, Oñate prayed, "Open the door of heaven to these heathens, establish the church and altars where the body and blood of the son of God may be offered, open to us the way to security and peace for their preservation and ours, and give to our king, and to me in his royal name, peaceful possession of these kingdoms and provinces for His blessed glory. Amen." [12] The Adelantado at Pecos For weeks the Pecos knew they were coming. But not until July 25—feast day of Santiago, as the invaders reckoned it—did the latest army of Spaniards draw up before the impressive eastern pueblo. Leaving his cumbrous wagon train behind, Juan de Oñate had ridden ahead with some sixty armed and mounted men to receive the homage of his Pueblo subjects. He had encountered no resistance among Piros, Southern Tiwas, Keres, Northern Tiwas, and Tanos. Now he beheld "the great pueblo of Pecos," subdued eight years earlier by Gaspar Castaño de Sosa only after a fierce battle. "This is the province Espejo called Tamos, from which came a certain don Pedro Oroz, an Indian of this land who died at Tanepantla under the care and instruction of the Franciscan Fathers." [13] Standing nearby in his abbreviated Franciscan habit was the Mexican Indian donado Juan de Dios. He had learned the language of this pueblo from the abducted Pedro Oroz. He interpreted for the governor and the two friars present, Comisario Alonso Martínez and Fray Cristóbal de Salazar, a cousin of don Juan. Two of Oñate's men, likely on hand this day, had fought in the battle of 1590—the medium-built, brown-bearded Ensign Juan de Victoria Carvajal and graying Juan Rodríguez, a Portuguese who would soon desert the New Mexico colony "at full gallop." A couple of weeks earlier at the Keres pueblo of Santo Domingo, where he had received in a large kiva the submission and vassalage of several native leaders, don Juan apprehended two of Castaño's Indians, Tomas and Cristóbal. They had been there since 1591 and spoke Keresan. They too stood with the Spaniards before Pecos. Even though he had Juan de Dios, interpreter in the language of this pueblo that called itself Cicuye, Oñate consistently used the Keresan name Pecos, as did the soldiers and Indians of Castaño, and everyone who came after them. This day the Pecos chose not to fight. Apparently they permitted the Spaniards the usual ritual acts—the harangues and planting of the cross and volleys. In honor of the day, the friars assigned Santiago as patron saint of the Pecos. The governor and his party left the next day. Six weeks later, after the Spanish colony had settled in at San Juan pueblo among the Tewas, the "captains" of Pecos were summoned to present themselves there, along with principales from other pueblos who had not yet rendered obedience. Most likely Juan de Dios delivered the message. Whoever did, the Pecos responded. Like Coronado, the bold Oñate had appropriated an entire native pueblo as his headquarters. Its name sounded to the Spaniards like Ohke. They had christened it San Juan Bautista. Here Oñate had set colonists and Indians to work building the first church in New Mexico, "large enough to accomodate all the people of the camp." By September 7, it was far enough along to dedicate. The following day, Tuesday, feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, the Spaniards crowded inside for solemn high Mass with all ten friars assisting. Father Commissary Martínez consecrated altar and chalices. Fray Cristóbal de Salazar delivered the sermon.

Oñate's Grant to the Friars When the Last Gospel had been sung, Oñate's secretary Juan Pérez de Donís, a man of medium build with gray beard and an old scar across his forehead, stepped to the front to read a proclamation from the governor. "In loud and intelligible voice" he began in the name of "don Juan de Oñate, governor, captain general, and adelantado of the kingdoms and provinces of New Mexico and those adjacent and bordering, their pacifier and colonizer for the king our lord, etc." Having been in this land since May and having personally pacified more than one hundred leagues of it, the governor deemed that the time had come to realize the expedition's highest purpose—"the conversion of the souls of these Indians, the exaltation of the Holy Catholic Church, and the preaching of the Holy Gospel." He had therefore summoned the native captains and principal men "with an Indian messenger and a small book of mine as a memento," and they had come.

Juan Pérez de Donís caught his breath. He had reached the critical point—Oñate's concession of New Mexico to the Franciscans.

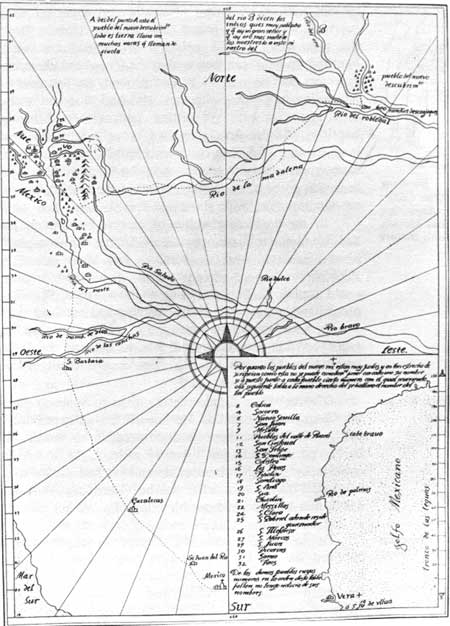

The secretary then intoned the list of provinces and pueblos, stretching from the Piros in the south to Taos in the north and from the Hopis in the west to "the province of the Pecos situated to the east of us, with the Querecho and Serrano Indians of its district," The proclamation concluded with an assurance to the friars that the king would sustain them with his royal alms in temporal matters while "they sustain their pueblos in spiritual matters." Father Commissary Martínez accepted for himself, his brethren present, and all sons of St. Francis. In order that Oñate's laudable act might be of lasting record, the Franciscan superior requested a copy of the concession. When he had signed with the governor's principal officers, the formalities concluded. Don Juan de Oñate, broadly interpreting his instructions and his authority, had installed the friars "for all time." [14]

After they had consecrated their church and provided for the conversion of heathen souls, the Spaniards gave themselves over to "great celebrations," singing, dancing, jousting, gaming, and the like. As a climax, they treated the assembled Pueblo leaders to a thoroughly Iberian ceremonial, "a good sham battle between Moors and Christians, the latter on foot with arquebuses, the former on horseback with lances and shields." [15] The Pueblos Render Homage The next day, September 9, 1598, the governor bid the native leaders "of the Tiwas, Puaray, Keres, Zias, Tewas, Pecos, Picuris, and Taos" join him in the main kiva. There in the presence of his officers, the friars, and his secretary, don Juan explained "the purpose of his coming and what was best for them." He spoke through at last four interpreters, including "the beloved brother Juan de Dios, Franciscan donado, interpreter of the language of the Pecos." He used words suggested by the ordinances of 1573 and his instructions from the viceroy,

Then, in the close atmosphere of the kiva, he gave them a lesson in elementary theology: one God, creator of the universe and judge of all men; good and evil; heaven and hell; God's servants on earth, the Roman pontiff and the Spanish king. He admonished them to obey and respect the representatives of pope and king. When the seated Pueblo principales "understood the meaning of this explanation, they replied through their interpreters that they of their own free will desired to render . . . obedience and vassalage to God and king." As a sign of their commitment Oñate instructed each of them in turn to rise, approach Father Commissary Martínez and him, kneel, and kiss their hands. It would be very much to their advantage, the adelantado continued, if they would take the Franciscans to their pueblos so that these men of God could learn their languages, instruct them in the Christian faith, baptize them, and thereby save their souls from the fires of hell. The Indians agreed. Before dismissing them, the Spaniards cautioned that they must treat the padres well, support them, and obey them in everything. He repeated this three times. If they failed to heed their friars or harmed them in any way, "they and their cities and towns would be put to the sword or burned alive." They said they understood. Missionaries Assigned Next Oñate and the Father Commissary, who had agreed beforehand, assigned the missionaries.

After all the priests and pueblos had been matched, the Indian principales in attendance were told to kiss the hand of the friar assigned to them "and to take charge of him." That concluded the rite. A week later Sargento mayor Vicente de Zaldívar led a well-mounted and well-supplied Spanish column, some sixty strong, out of San Juan bound for the buffalo plains. Fray Francisco de San Miguel and donado Juan de Dios accompanied them as far as the teeming pueblo of Pecos, which they reached September 18, 1598. After two days, the expedition moved out, leaving the aged friar and his assistant to begin their ministry to the Pecos people. It lasted not three months. [17] The Ministry of Francisco de San Miquel Fray Francisco was old in years and poor in worldly goods, full of his God the Father, God the Son, Holy Poverty, and a Blessed Mother, none of which necessarily offended the Pecos. This elderly Franciscan already knew some words in their language, words he had learned from Juan de Dios. He wanted to know more. Three years later, when he was "seventy years old more or less," Fray Francisco testified that he had begun learning four native languages, "that he had worked very hard at it, and that he had labored with the Indians and native people to convert them and bring them to the holy gospel." But he admitted to "very great difficulty" in his ministry because other Spaniards abused the Pueblos. [18]

Despite his advanced age, Francisco de San Miguel had not been a friar as long as he might have been. Evidently he had entered the Order in 1570 relatively late in life, at the age of forty or so. After the year-long novitiate, he professed his religious vows on April 18, 1571, at the Holy Gospel province's convento in Puebla. A cumulative provincial roster compiled in the eighteenth century provided no further information about him, not even his place of birth. A decade after his profession—about the time of the Sánchez Chamuscado and Espejo entradas—Fray Francisco had set out for the frontier. Unfortunately he was not a theologian, an administrator, or a martyr, so the chroniclers ignored him. Only as a participant in the Oñate enterprise did he emerge again. [19] Father San Miguel's apostolic labors at Pecos are as shadowy as the rest of his life. There is no record of his acceptance or rejection by the people: how many baptisms of Pecos Indians in danger of dying, if any, he performed; how many of his assigned Tiwas, Tompiros, Jumanos, Apaches, and others, if any, he visited. It is not known whether at this early stage Fray Francisco chose to confront the "idols" in Pecos kivas, as did a successor twenty years later. The First Church at Pecos There is only one tangible clue to San Miguel's ministry, and even it is questionable. On a narrow, piñon-studded ridge, a thousand feet more north than east of the main Pecos pueblo, archaeologists uncovered the ruins of a simple, rectangular adobe church built, in their opinion, "not later than in the first two decades of the 1600's." Near the trail the Pecos used going and coming from their fields along the river, the site afforded a dramatic vista of tiered pueblo set against massive, reddish cliffs of the mesa beyond. The church faced south, more or less in the direction of the pueblo, rested on a rather narrow but well-laid stone foundation, and measured inside roughly twenty-five by eighty feet. It had been roofed and mud-plastered inside and out. An unfinished sacristy, containing some two hundred and fifty stacked adobes, clung to the east wall. Because the level area was barely wide enough for the church alone, and the bedrock near the surface, the builder cannot have planned to adjoin either convento or cemetery. Just north of the church, however, where the ridge broadens out, he could have built either. If ever the structure was used, it must have been only briefly. The excavators found no trace of European artifacts. [20] The distance of church from pueblo may be evidence of Pecos resistance. If in fact Father San Miguel and donado Juan de Dios were supervising construction of this first Pecos church during the fall of 1598, they left in a hurry. Early in December, chilling news reached them. When he had received the vassalage of Pueblo leaders and distributed the Franciscans among them, don Juan de Oñate had set about exploring his huge domain in earnest. He had dispatched Vicente de Zaldívar to the buffalo plains to report all he saw, to contact the natives, and to find out if the "cows" could be domesticated. Oñate himself had ridden out in October to assess the value of the salines east of the Manzano Mountains and to receive homage from nearby pueblos. From there he headed westward for the sea. At the pueblos of Ácoma, Zuñi, and Hopi, he and his men had been received without incident and given water, maize, and turkeys. He had sent a captain to verify the Zuñi salt lake and some silver deposits the Hopis had described. Then in mid-November, he turned back to the Zuñi pueblos to await the appearance of his elder nephew Maese de campo Juan de Zaldívar with reinforcements for the trek to the South Sea.

Zaldívar Murdered Zaldívar never made it. He and his column had stopped at Ácoma to exact provisions. Invited up onto the penol with a small party on December 4, the maese de campo had walked into a trap. He and a dozen of his men, fighting savagely hand-to-hand in the sudden onslaught, went down under swarms of Ácoma warriors. A few Spaniards escaped. Within days Oñate knew. As word spread, the governor led his men back to San Juan. The missionaries and their helpers hastened in from their posts on orders from Father Commissary Martínez. Father San Miguel and Juan de Dios abandoned Pecos. Evidently the people razed the church and used some of the beams and adobes to construct a kiva. No missionary would live at Pecos for another twenty years. At San Juan, the hastily assembled colony prepared to meet the crisis. Oñate listened to survivors recount the tragedy. He established for the record two important facts: that the attack on Zaldívar's force had been deliberate, premeditated, and treacherous; and, that until the Spaniards laid waste the defiant fortress-pueblo of Ácoma, there could be no peace in the land. The governor next called upon Father Commissary Alonso Martínez for a definition of just war. The friar, dutifully citing scripture, church fathers, philosophers, and legalists, concluded, "Finally, if the cause of war is universal peace, or peace in his kingdom, he [i.e., the Christian prince] may justly wage war and destroy any obstacle in the way of peace until it is effectively achieved." The five Franciscan priests on hand, including Father San Miguel, affirmed their superior's "very Christian and learned" opinion. After Mass on January 10, 1599, the colonists resolved at a general meeting that Ácoma must be punished at once: any delay would see the entire kingdom in rebellion against the Spaniards.

The Harsh Punishment of Ácoma

Taking seventy soldiers—about half the colony's total force—the slain Zaldívar's younger brother Vicente set forth to humble the rebels of Ácoma. Incredibly enough, he did just that. In a bold and well-engineered two-day assault, he carried and sacked the "impregnable stronghold." According to Spanish sources, the Ácoma men, sensing defeat, began to kill one another and their families rather than surrender. The invaders took as many captives as they could, "upwards of five hundred men, women, and children." At populous Santo Domingo, an elated Oñate met the returning heroes and dealt with the Ácoma prisoners. All the Pueblos watched. They did not understand the formalities of the trial the Spaniards recorded so diligently, but they saw the brutal results. Ácoma males, twenty-five and older, the governor sentenced to have one foot hacked off. Like the young men and the women, these defeated and mutilated warriors must in addition serve twenty years as slaves of the invaders. Two Hopis caught at Ácoma were to lose their right hands and "be set free in order that they may convey to their land the news of this punishment." [21] Oñate Appeals for Help The next serious threat to Oñate's rule came not from rebellious Pueblo Indians, but from his own hungry, disillusioned colonists. For two long years they prospected in all directions for the rich lodes that would make New Mexico another Zacatecas, while all the time their families endured a mean existence dependent on what tribute of maize and blankets they could exact from sullen Indians. Oñate professed excitement over meager assay reports. In hopes of further government support, he wrote to viceroy and king describing the expanse of the new land, its tens of thousands of town-dwelling vassals, the potentially rich silver mines and South Sea pearl fisheries, the salines, and the fertile soil. On the plains to the east were untold multitudes of Cíbola cattle and great settlements of natives. "It would be an endless story," he avowed, "to attempt to describe in detail each one of the many things that are found there. All I can say is that with God's help I am going to see them all and give to His Majesty more pacified worlds, new and conquered, greater than the good marques [i.e., Cortés] gave him . . . if your lordship but gives me the succor, favor, and aid I expect from such a [generous] hand." [22] In the spring of 1599, Oñate sent this appeal to Mexico City with Fathers Martínez and Salazar, recruiters, and an escort. Among the supporting documentation they carried was the testimony of one Jusepe Gutiérrez, Mexican Indian servant and interpreter, who had entered New Mexico about 1594 with Captain Leyva de Bonilla, the outlaw Oñate was commissioned to apprehend. According to Jusepe, Leyva's party had spent about a year among the Pueblos, most of the time at San Ildefonso. From there they had gone "through the pueblos of the Pecos and Vaquero Indians" far out onto the plains to "the Great Settlement." Soon after, Jusepe's master, Antonio Gutiérrez de Humaña, stabbed Leyva to death with a butcher knife, whereupon half a dozen Indian servants including Jusepe made their escape. He alone, after numerous adventures, had made it back to New Mexico. [23] The Ácoma troubles had sobered the friars. Now they stuck closer to the Rio Grande. Father San Miguel did not go back to Pecos. In the absence of Father Commissary Martínez, he functioned as vice commissary at the colony's sorry "capital." Perhaps to make room for their numerous Ácoma slaves, the Spaniards moved across the river to the larger west-bank Tewa pueblo of Yunqueyunque, renaming it San Gabriel. All rejoiced on Christmas Eve 1600 when the caravan of reinforcements, supplies, and stock—for which Oñate's relative had earlier given bond—trudged into San Gabriel. With them came seven new friars ready and eager to expand the New Mexico apostolate. Still, none of them ventured to live among the Pecos. [24]

New Mexico's first superior, Fray Alonso Martínez, did not return with the new friars. Fray Juan de Escalona, his replacement as commissary, meant to consolidate missionary effort along the Rio Grande, and he assigned his men accordingly. The venerable Father San Miguel moved down to San Ildefonso only ten miles south of the capital. Testifying in October 1601, Capt. Bartolomé Romero told how we had seen "the Tewa Indians at San Ildefonso, where Fray Francisco de San Miguel was guardian and where they have built a church, come to prayers and to work on the convento." [25]

Desertion of the Colonists Still, the colony was bitterly unhappy in 1601. The new settlers may have provided security but they too had to be fed. Prospects of easy wealth faded daily. Oñate, grasping for truth in the reports of Jusepe Gutiérrez, took half the colony's armed men, Vicente de Zaldívar, a couple of friars, more than seven hundred horses and mules, eight carts, and four pieces of artillery, and embarked in late June via Galisteo for the great plains. With the governor gone, talk of desertion surfaced. Only Oñate's iron rule and harsh treatment of previous deserters had kept the majority of colonists from fleeing before this. The suffering of their women and children, the plagues of bedbugs and lice, the unbearable cold of winter, the sullen looks of the Indians—how they despised this place. They had a saying about New Mexico: Ocho meses de invierno y cuatro de infierno! Eight months of winter and four of hell! [26] Even the friars—later accused by Oñate of fomenting mutiny—spoke gloomily of giving up, of leaving for "a place where His Majesty might be informed of the many legitimate causes for taking this step." Unlike Father Commissary Juan de Escalona, who stayed out of it, old Father Francisco de San Miguel, "vice commissary in these provinces with full powers," preached the abandonment of New Mexico. Testifying in the convento at San Gabriel before Lt. Gov. Francisco de Sosa Peñalosa, the disillusioned San Miguel and four of his fellow Franciscans described the grinding poverty and desolation of the colony. To extract every kernel of stored maize, desperate Spaniards had taken to torturing Indians. Drought had parched the milpas. "If we stay any longer, the natives and all of us here will perish of hunger, cold, and nakedness." [27] When Governor Oñate and his explorers reappeared late in November no more than two dozen colonists turned out to greet them. The others had deserted. Treason, averred don Juan as he ordered Zaldívar after them. But they had too great a lead. They had made it to Santa Bárbara, beyond the adelantado's jurisdiction. They did not have to go back. Their bold protest had drawn the attention of the viceroy. The entire New Mexico endeavor would now be reevaluated. Don Juan's luck had not changed.

New Mexico in the Balance All the Franciscans, except Father Commissary Juan de Escalona and the two friars with Oñate, had gone. They had abandoned every mission in New Mexico. Even the governor's confessor, the "saintly old barefoot and naked-poor friar named Fray Francisco de San Miguel, over seventy-four years of age," had willingly joined the exodus. Father Escalona, who had given the others his blessing and had himself written damning indictments of Oñate's rule, remained at San Gabriel to make a point: the Franciscans did not want to give up New Mexico permanently. But because Oñate lacked resources, because he condoned the plunder of the Pueblos, because he oppressed the colony, "we cannot preach the Gospel now, for it is despised by these people on account of our great offenses and the harm we have done them." The friars begged the government to take over the colony. [28]

Just how many persons they had baptized in New Mexico no one seemed to know. They had administered the sacrament to sick Indians in danger of death, and some no doubt had survived. They had baptized some Pueblo children. Because of the uncertainty of the colony's future and because a few baptized Indians ran away, they had confined themselves for the most part to natives in and around the Spaniards' camp. According to several witnesses who had stood as godparents, the friars, just before deserting, had celebrated two general baptisms. At the first, they had brought into the church "a large number of Indian children belonging to the women slaves from Ácoma and many natives in the service of the Spaniards from the pueblos where we reside;" at the second, a number of women servants, both slave and free. In the conflicting welter of reports by Oñate's partisans and his detractors, the matter of Indian baptisms became a pivotal issue. If there were only a few Christians among the Pueblos, and these already in the Spaniards' employ, they could simply be brought along to New Spain. But if, on the other hand, many and diverse natives had received the saving water, how could the crown in conscience withdraw the colony? While government officials, jurists, and theologians debated New Mexico's fate, the Franciscans consigned another six workers to the vineyard. [29] Oñate Resigns The embattled Oñate sent Zaldívar to Spain to plead with the Council of the Indies. He himself led an expedition to the Gulf of California where he discovered, in his words, "a great harbor on the South Sea." But try as he might, the adelantado could not dispel the cloud of doubt that had settled over New Mexico. Finally, in a letter to the viceroy dated August 24, 1607, don Juan poured out his bitter cup and resigned. [30] Baptisms Save the Colony Between 1601 and 1607, estimates of the number of baptized Indians in New Mexico ranged from five dozen to more than six hundred. Viceroy Marqués de Montesclaros, who succeeded Monterrey, had advised the king in 1605 that even "if there should be one lone Christian, Your Majesty would be obliged by justice, conscience, and reputation to preserve him, even at great cost to the royal treasury." Knowing that it would take more than one convert to loosen the royal purse strings, a Franciscan, just returned from New Mexico late in 1608, reported a figure so high that it could only have resulted from truly prodigious evangelical effort, or gross exaggeration—more than seven thousand!

But Fray Lázaro Jiménez knew what he was about. He had first gone to New Mexico in 1603 or 1605 and returned late in 1607 "to beg in the name of all" that the crown either send men, clothing, and livestock, or permission to abandon the colony. If they received no orders to the contrary by June 1608, they would all leave. The king meantime decreed that exploration cease, that Oñate be replaced, but that the colonists stay on until a final decision had been reached. Viceroy Luis de Velasco, back in New Spain for a second term, favored abandonment and the withdrawal of Christian Indians. But he had used Father Jiménez, sent back again to New Mexico with escort and supplies, to advise Oñate and the settlers not to leave until further word from Spain, at last not before December 1609. Only when the friar reached the colony in 1608 had he found out, marvelous to relate, that a couple of his brethren in six months had baptized thousands. [31] Whether fact or fiction, "the more than seven thousand" sudden Pueblo converts saved New Mexico for the friars. Obviously, wrote Velasco to the king, "we could not abandon the land without great offense to God and great risk of losing what has been gained." With unusual dispatch, the viceroy arranged for reinforcements, more supplies, more friars, and a royal governor to take over the colony's administration from the lord proprietor Oñate. By late 1609, the whole outfit was on the road north. [32] Oñate waited impatiently at San Gabriel. By early February 1610, soon after he had received the officious new governor, one don Pedro de Peralta, the undone adelantado took his leave. After all his trouble, after all the past fifteen years of his life, after all the six hundred thousand pesos he and his associates had spent on the New Mexico venture, don Juan de Oñate braced himself not for a hero's welcome but for a trial on criminal charges. Another México, another Cortés, at this point nothing could have been farther from his mind. A Royal Missionary Colony New Mexico plainly was not an asset to anyone but the Franciscans. The decision to convert it from proprietary to royal colony rested not on economic potential, but on Christian obligation. A pious monarch, Philip III could not in conscience turn his back on thousands of baptized Indians. And no one challenged the friars' claim. Neither Luis de Velasco, the well-respected viceroy who had originally given Oñate the contract, nor don Juan himself looked as bad in the light of so rich a harvest of souls. They had made the best of a bad bargain. As for the friars, they now enjoyed an advantage over everyone else in the colony. Because the government had pronounced New Mexico a vineyard of the Lord, they as the Lord's ordained workers were indispensable. Clearly, in their minds, the layman-colonist existed to aid and protect the missionary. The friars appeared to have it all their own way. No rival order competed with them. There was not a single diocesan priest anywhere in New Mexico, which meant that the faithful had no one else to turn to for the sacraments. No bishop exercised effective jurisdiction over the isolated colony. New Mexico had become an ecclesiastical monopoly of the Franciscans. They were the Church. The only check on the friars was the royal governor. As the colony's chief executive, legislator, and judge, as well as commander of the meager military, he wielded a countervailing force as concentrated and as potentially tyrannical as theirs. He and his appointees were the State. The colonist, exhorted by both masters, had often to choose between the two.

The Struggle of Church and State Rarely in seventeenth-century New Mexico did the minions of church and state coexist in harmony. They fought, at times physically, over the poor colony's prime resource—the Pueblo Indians. The governors' belligerent exploitation of the natives for personal profit ran head-on into the friars' jealous paternalism. Never did the viceroy define precisely the respective jurisdictions of church and state in New Mexico. Even if he had, appeal from the colony took so long that it was no deterrent to criminal acts. Thus, from the arrival of don Pedro de Peralta in early 1610 until the Pueblos revolted in 1680, the single most notorious feature of life in colonial New Mexico was the war between the governors and the Franciscans. [33] If the viceroy intended his governor of New Mexico to be the friars' lackey, he did not say so. The instructions Velasco issued to Peralta, a royal bureaucrat trained in the law, stressed putting the foundering colony on a firm footing. First, he must lay out a new municipality for the colonists "so that they may begin to live in some order and decency." By peaceful means or by force, he must defend New Mexico and restore respect for Spanish rule. Where the Indians lived dispersed, Peralta was to consolidate them. He must not allow further exploration by colonists "since experience has shown that greed for what is out of reach has always led them to neglect what they already have." The viceroy's admonition to proceed in certain matters in consultation with the friars and persons of practical experience" in no way implied subservience. [34]

Despite the alleged burst of evangelization in 1608, only two or three friars were left in New Mexico when Governor Peralta arrived. With him came Father Commissary Alonso Peinado, fifty-five-year-old native of Málaga, and eight others. In 1612, a second supply train lumbered up the valley of the Rio Grande bringing nine more. [35] This put the missions of New Mexico on a solid basis for the first time. It also set the stage for the scandalous first round of the church-state conflict. Ordóñez versus Peralta If later on, crude, heavy-handed governors deserved a greater share of the blame, this time it was a crude, heavy handed Franciscan. Fray Isidro Ordóñez was everything a friar should not have been: personally ambitious, hot-headed, scheming. He had been in New Mexico twice before and had come back again as superior of the mission supply caravan of 1612. Perhaps he meant to establish the church's supremacy over the state once and for all, to set the precedent. Whatever his intent, the methods he used alienated some of his own brethren. Even before he reached Peralta's new villa of Santa Fe, he had begun his play for power. At Sandía, southernmost of the mission pueblos, Ordóñez produced a patent allegedly making him the new Father Commissary. The "saintly" Fray Alonso Peinado yielded. Later, another friar pronounced the document a forgery. In Santa Fe, the overbearing Ordóñez insisted that Gov. Pedro de Peralta proclaim at once a viceregal order allowing any dissatisfied soldier-colonist to leave New Mexico at will. The governor protested. Ordóñez had it proclaimed anyway. Then he accused Peralta of underfeeding the natives working on public projects in Santa Fe. In May 1613, an even better chance to humble the royal governor presented itself. Peralta had dispatched several soldiers to collect the spring tribute of maize and mantas from Taos. At Nambé the busy Ordóñez intercepted them and turned them back to Santa Fe to celebrate the Mass of Pentecost. Livid, the governor sent them out again. They could hear Mass at some pueblo along the way. At that, Father Ordóñez excommunicated don Pedro and posted the notice on the doors of the Santa Fe church. A whole series of incidents followed as harried governor and overzealous friar sought to enlist partisans from among the colonists. During a lull, worried citizens prevailed upon the prelate to absolve the governor. Other disputes, one over a levy of Indian laborers from San Lázaro, erupted in rapid succession. Then on a Sunday in July, don Pedro found the chair he was accustomed to occupy at church thrown outside in the dirt. Holding his temper, he had it picked up and placed in the back near the baptismal font. There he sat down among the Indians. Shortly, a grim-faced Father Ordóñez mounted the pulpit.

Next day the prelate, expecting servile compliance, requested that the governor loan him several soldiers to collect the tithe, Peralta refused. The soldiers were in the king's employ. Besides, there were no tithes to collect. Furious over this rebuff, the Franciscan branded the governor a Lutheran, a heretic, and a Jew, and threatened to arrest him. That was too much for don Pedro. Taking several armed men, he marched across the plaza to the Franciscan convento and ordered the Father Commissary to leave town. A scuffle ensued. The governor's pistol discharged wounding a lay brother and a soldier. Ordóñez straight-away reexcommunicated his adversary, ordered the host consumed and the church locked, and then rode to Santo Domingo to address an urgent council of all the clergy. The Governor Imprisoned With matters in the colony verging on civil war, don Pedro de Peralta resolved to take his case to Mexico City in person. Spies informed Father Ordóñez. In the middle of the night of August 12 near Isleta, the prelate and his gang descended on the governor's camp and arrested him. At Sandía, whose guardián Esteban de Perea disapproved, the governor was thrust in a cell in chains. For the next nine months, Fray Isidro Ordóñez ruled New Mexico unchallenged. "Excommunications were rained down," according to one horrified friar, ". . . and because of the terrors that walked abroad the people were not only scandalized but afraid . . . existence in the villa [Santa Fe] was a hell." Even when a new governor, don Bernardino de Ceballos, entered New Mexico in the spring of 1614, he was forced to acknowledge the strength of the Ordóñez faction and to proceed cautiously with his investigation of the previous administration. Ex-governor Peralta was not allowed to depart the colony until the following November, then only after Ceballos and Ordóñez had despoiled him of most of his possessions. For another two years, the stormy Father Ordóñez held on as prelate of New Mexico despite growing discontent among the friars. Evidently at a council of the clergy, he and Father Peinado came to blows. He also fell out with the new governor, mainly over use and abuse of Pueblo Indians. Not until the next mission supply caravan reached the colony in the winter of 1616-1617 did the tumultuous reign of Fray Isidro Ordóñez come to an end. In just four years, he had indeed established the precedent—doubtless justified to some extent by outrages on the other side—for a malignant, divisive tradition of church-state discord.

And of course the Pueblo Indians, ordered in the name of the king to do one thing and in the name of the church to do another, took it all in and bided their time. [36] During these years, the Spaniards did not often mention Pecos. Fray Francisco de Velasco, a missionary in New Mexico from 1600 to 1607, did report that the Pecos had joined an alliance against the Tewas and other Indians who were aiding and abetting the invaders. "Because those Indians have shown so much friendship for the Spaniards they have lost the good will of the Picurís, Taos, Pecos, Apaches, and Vaqueros, who have formed a league among themselves and with other barbarous nations to exterminate our friends." This would surely happen, Father Velasco told the king, if the Spaniards pulled out of New Mexico. [37] Exacting Tribute from the Pueblos As vassals of the Spanish crown, all the Pueblo peoples owed tribute. In the words of the 1573 colonization laws, Indians who rendered obedience "should be persuaded to pay moderate amounts of tribute in local products." The crown reserved the right to collect this revenue only "from principal towns and seaports," a hopeful clause that did not apply on the northern frontier. Tribute from all other native settlements was conceded by the crown to the colonizers themselves. [38] By the terms of his contract, don Juan de Oñate could reward his followers by granting them so many Indian tributaries. The number, from several entire pueblos to a fraction of one, depended on the colonist's rank and the services he had rendered. In no legal sense did a grant of Indians in encomienda (literally, in trust), good for three lifetimes in succession, imply use of native land or labor, but rather only the collection of tribute in kind as personal income, usually maize and mantas or animal skins. In turn, the encomendero, recipient of an encomienda, swore to answer the governor's call to arms, providing his own horses and weapons, whenever the need arose. He was also required to maintain residence in Santa Fe. Since there were no regular troops in seventeenth-century New Mexico, the encomenderos, whose number was later set by the viceroy at thirty-five, became the core of the local military. As officers, customarily designated captain by the governor, they rode escort, served as guards, and commanded levies of lesser colonists and native auxiliaries in the colony's defense. [39]

To keep from starving, Oñate and his men had collected tribute from the beginning, sometimes by violent means. Just how many pueblos the adelantado committed to individual colonists is not clear. He did commit some. [40] In New Mexico, stark necessity evidently precluded the customary decade of exemption from tribute applied in some new missionary areas, although from time to time, the friars alluded to it. Governor Peralta's instructions contained the standard admonition that when granting encomiendas, he must not prejudice those awarded by his predecessor. And like Oñate, the perplexed Peralta tried to feed his colony by collecting the tribute from pueblos not yet held by individuals. Potentially, Pecos was the richest encomienda in New Mexico. If Oñate himself did not grant it to some worthy colonist, one of his successors must soon have done so. [41] Abandonment of San Gabriel in favor of Santa Fe during the spring of 1610 brought the Spaniards much nearer to the teeming eastern pueblo. Both the lure of the pueblo-plains trade and the lure of souls aroused their interest. Within a year or two, the Franciscans had established a convento among the Tanos at Galisteo. The arrival of seven friars during the winter of 1616-1617 made possible even greater missionary outreach. And one of their objectives was Pecos. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||