Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

The 18th-Century Revolution in New Mexico If Fray Alonso de Posada had been resurrected in eighteenth-century New Mexico, he would hardly have recognized the place. Not that the Jornada del Muerto or the Sierra de Sandía looked any different; not that the mainly agricultural subsistence-level economy had changed, or the pattern of trade and hostilities with surrounding nomads, or the drought, disease, and isolation, but rather, the colony's very reason for being. The Pueblo revolts and the reconquest by Diego de Vargas—set in the larger context of an increasingly secular world—had thrust up a watershed. The blood of the martyrs flowed back to the age of spiritual conquest, the age of Fray Juan de Padilla and Fray Alonso de Benavides, while the tide of the future ran on toward the mundane, toward colonial rivalry, solicitation of sex in the confessional, and even constitutions. Defense had replaced evangelism. Friars no longer dictated the affairs of the colony. The primary concerns of the Spanish Bourbon kings and their colonial bureaucracy were defense and revenue, not missions. Where missionaries held or strengthened imperial frontiers, as they did in New Mexico, they continued to receive compensation from the crown. Still, the mission payroll declined in proportion to that of the military. In 1763, thirty-four Franciscan priests received an annual sínodo, or royal allowance, of 330 pesos each, and one lay brother, 230, for a total of 11,450 Pesos—as compared to 32,065 pesos for the Santa Fe garrison. The salaried presidial, too often ill-equipped, poorly trained, and abused by his officers, had replaced the soldier encomendero. In New Mexico, the encomienda system, dying all the empire, did not survive 1680. [1] No longer did Franciscans control the economic lifeline of the colony. The government-subsidized mission supply service that operated for much of the seventeenth century was not restaged in the eighteenth. Instead, like everyone else, the friars made their own arrangements for freighting. The missions' combined wealth, using the word loosely, fell in proportion to that of the steadily expanding Hispanic community. Few pre-revolt families returned. The settlers who came with Vargas and those who came later wrought, in effect, "a new and distinct colonization." By 1799, a census, including the El Paso district, showed 23,648 of them—and only 10,557 Indians. [2] Although friars continued as the only priests to the vast majority of New Mexicans, they saw their monopoly of the local church seriously undermined in the eighteenth century. Three bishops of Durango actually appeared in the colony on visitations—Benito Crespo in 1730, Martín de Elizacoechea in 1737, and Pedro Tamarón in 1760. Crespo appointed New Mexico-born don Santiago Roybal, whom he had previously ordained at Durango, as his vicar and ecclesiastical judge in Santa Fe, an opening wedge for the secular clergy. A Franciscan still served as agent of the Inquisition, but his authority was only a shadow of what it had been. Compromised by the "flexible orthodoxy" of reforming Bourbons, the Holy Office now too often spent its energy hairsplitting or protecting its own privileged status. As guardian of traditional Hispanic values against the blasphemy of the Enlightenment, it had little business on an illiterate frontier. Unless the governor of New Mexico happened to profess French philosophy, Protestantism, or Freemasonry, unless he had two wives or was grossly immoral, he ran little risk of accusation, arrest, or trial by the Inquisition, even when he trod on the friars' toes. At times, in fact, the tables were turned. Denunciation of the missionaries themselves for solicitation or worse became a weapon of the laity. [3] Most of the bluerobes ministered faithfully to their motley flocks of Indians and Hispanos, even under the most trying conditions. Some were sorely perplexed by the conflict inherent in being both missionary and parish priest, striving to observe with the right hand the Rule of St. Francis, while accepting with the left, fees for services rendered. Some broke under the strain. A few were scoundrels. Overall, it would seem, the quality of the clergy did decline in eighteenth-century New Mexico. Within the Order, missionary momentum shifted from the provinces to the newly formed missionary colleges whose grayrobed friars answered the call to Coahuila-Texas, the Californias, and Sonora-Arizona. Nothing wounded the dedicated, beleaguered New Mexico missioner more than the gaping disparity between the pious expectations of the seventeenth century and the scabby reality of the eighteenth.

The Administration of Cuervo y Valdés Diego de Vargas, heroic reconqueror and strutting peacock, was dead. The viceroy, then the Duke of Alburquerque, hastily appointed a governor ad interim, one don Francisco Cuervo y Valdés, knight of the Order of Santiago, who entered Santa Fe in March 1705. By the end of that year, Cuervo had recruited enough settlers to found a new villa in the Bosque Grande de doña Luisa, the future Albuquerque. He had arranged for the repeopling of Galisteo with some of the dispersed Tanos. He had waged war on Navajos and Apaches, and he had presented to don Felipe Chistoe of Pecos and to other loyal Pueblo leaders "suits of fine woolen Mexican cloth like that used by the Spaniards" along with "white cloth for shirts, as well as hats, stockings, and shoes." The rest of the time, don Francisco spent trying to convert his interim appointment to a regular one. The Pueblo Indians considered Cuervo a savior, or so he tried to convince the crown. At a concourse of their leaders who came together in Santa Fe in January 1706, these natives, on their own volition says the document, begged through their protector general, Alfonso Rael de Aguilar, that "don Francisco Cuervo y Valdés be continued and maintained in this administration for such time as is His Majesty's will, so that they might enjoy not only the blessings of peace but might also make progress in those things which they hoped to achieve through his Catholic and successful programs, of which they were very certain because of what they had already experienced of his prompt and sure actions." Representing the Pecos, as usual, was the Spanish-speaking don Felipe Chistoe. [4] Along with the Pueblo leaders' plea that he be retained in office, Cuervo sent to the viceroy a supplication by Custos Juan Álvarez. The missions of New Mexico desperately needed vestments, chalices, and bells. They needed reinforcements, another thirteen friars in addition to the twenty-one already granted. Payment of their travel expenses had fallen three years behind. They lacked even wine and candles for Mass. In some missions, according to the prelate, "the chasuble is of one color, the stole of another, and the maniple of still another; and, they are without bells with which to call the people to catechism." To document his statement Father Álvarez supplied a mission-by-mission account of the custody.

A Basque from the salty coastal villa of Lequeitio, half way between Bilbao and San Sebastián, Fray José de Arrangui had professed at the Mexican Convento Grande on April 20, 1695, and had already begun his ministry in New Mexico by the year 1700. Pecos, where he baptized, married, and buried between August of 1700 and August of 1708, seems to have been his first and perhaps his only missionary assignment. How often he actually resided at the pueblo is hard to tell, but probably not often. For much of the time he served as notary and minister of Santa Fe as well. As secretary, he cosigned Custos Álvarez' glum report of January 1706. [6] New Church at Pecos Despite their inclination to look on Pecos as a visita of Santa Fe, the Franciscans did superintend the construction of a proper new church at the waning pueblo. Curiously, less is known about the building of this one than about either Zeinos' temporary reconquest chapel or the great pre-Revolt monument of Andrés Juárez. Custos Álvarez said about Pecos, "They are beginning to build the church." But he said the same thing about fifteen other pueblos, including Ácoma where the massive seventeenth-century structure had survived 1680 almost intact. Perhaps by sometime in 1705, Arranegui had made a start. An equally elusive statement, by the hyperobservant Father Visitor fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez in 1776, suggests 1716-1717 as the completion date. After counting the roof beams, "well wrought and corbeled" by Pecos carpenters, thirty-eight over the nave, twenty over the transept, and ten over the sanctuary, Domínguez noted a brief Latin inscription "on the one facing the nave: Frater Carolus. The inference is," he continued, "that a friar of this name was the one who built the church, but it is impossible to identify him since the individual is not identified by his surname." [7]

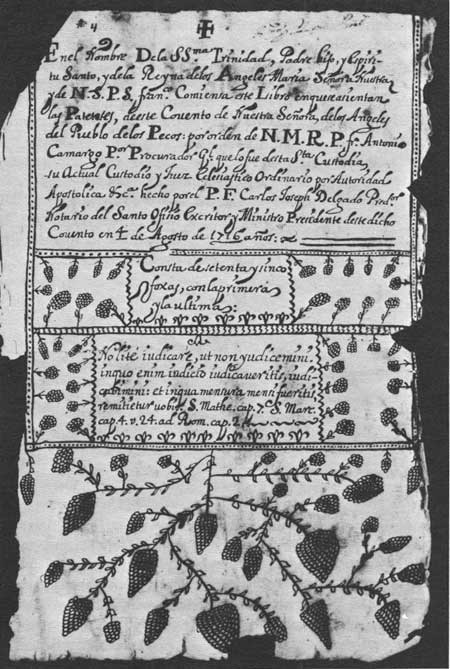

The Apostolic Fray Carlos The only friar named Carolus, or Carlos, who ministered at Pecos, or for that matter anywhere in the custody up to 1776, was an eighteenth-century Andrés Juárez named Carlos José Delgado. Described later as an "apostolic Spaniard," Delgado had been recruited from the province of Andalucía for the missionary college of Querétaro, had transferred to the province of the Holy Gospel, and in 1710 had arrived in New Mexico where he was to labor for forty years. By August 4, 1716, Fray Carlos, "ministro presidente" at Pecos, was bent over a desk in the convento decorating the title page of a new book for patentes, the official letters of exhortation and instruction from Franciscan superiors, which were regularly copied into such books at all the Order's houses. Although Delgado's baptismal and burial entries, which might have mentioned a "new church," are missing, his marriage entries survive, and they are distinctive. He wrote in a heavy, legible hand, and he filled the margins with garlands of curious, snowball-like flowers. Chronologically, the entries are bunched, seven in December-January 1716-1717, seventeen in April-May 1717, and three in October 1717, suggesting that he too divided his time between Santa Fe and Pecos. [8]

"The construction was done," wrote Fray Juan Miguel Menchero in 1744, "through the industry and care of the Fathers of the mission without having spent even a half-real of His Majesty's funds." The church, in his estimation, rated the adjectives "beautiful and capacious." Like Zeinos' chapel, it faced west, and it sat entirely on top of the mound covering Andrés Juárez' much larger fallen temple. The new church had barely three thousand square feet of floor space, compared to well over five thousand in the Juárez structure. But now there were fewer Pecos, not half as many. [9]

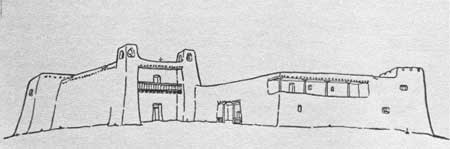

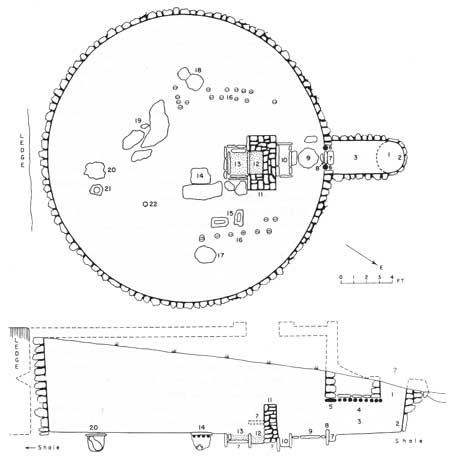

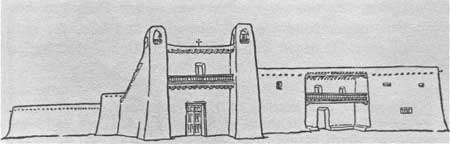

This was the fourth and final Pecos church. As late as 1846, eight years after the last few Pecos had abandoned the pueblo, artist John Mix Stanley of Lt. W. H. Emory's command sketched the deteriorating structure much as Father Domínguez had described it in 1776. Emory's comment that the details of the church "differ but little from those of the present day" is as true now as then. Its facade, flanked by twin bell towers rising barely above the flat roof, could hardly have been more typical of New Mexico church architecture. Between the bell towers, which jutted forward several feet forming a shallow narthex, and above the eight-foot-tall, two-leaved door, ran a wooden balcony with balustrade and roof. To get out onto it, said Domínguez, one exited from the choir loft through a window. Unlike the monumental seventeenth-century Juárez church, this one had neither buttresses nor crenelations, but it did have a transept. The floor plan was cruciform. In profile, the roof line ran straight back from the bell towers and stepped up at the transept allowing for a wooden-grated "transverse clearstory light." The outside, or north side, of the building presented one great expanse of adobe wall broken only by a single high window at the north end of the transept. On the south side, which looked out over the convento, there were at least three high windows. To reach the main door in 1776, it was necessary to enter the cemetery through a gate in the high wall directly in front. The porter's lodge and two-story convento were on the right. Once across the cemetery and inside, Father Domínguez found the dim interior of the church "rather pleasant." Above his head as he entered was the choir loft, to his right a door leading through Zeinos' dilapidated chapel to baptistery, sacristy, and convento beyond. The church floor was packed earth. Under it lay most of the baptized persons who had died over the previous sixty or seventy years.

Five steps led up to the sanctuary. Over the main altar, a movable wooden one, hung an old framed oil painting of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles and another, somewhat newer, of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, as well as eight lesser oils arranged around the other two. In both arms of the transept stood wooden altars surmounted by paintings, some on buffalo hide. Evidently the Pecos church boasted no statuary at all. Virtually nothing escaped Domínguez' eye. In the nave, there was a well-constructed wooden pulpit in its usual place on the epistle side, and on the gospel side "a pretty wooden confessional on a platform," then a long bench with legs. He described the sacristy and inventoried everything he found, item by item, from chasubles to thurible to missal. Next he toured the convento downstairs and up, identifying cells, store-rooms, and stables. Upstairs, only the rooms on the south side were usable in 1776. The others needed repair. Good miradors looked out to the south and the west, and in the southwest corner stood a fortified tower. "When there are enemies," he noted, "a stone mortar is installed in it." [10] In all, the physical plant at Pecos was more than adequate. The church, constructed sometime between 1705 and 1717, may even have deserved the adjectives "beautiful and capacious." If the friars' ministry to the Pecos in the eighteenth century proved ineffectual, as some of them admitted it did, the reasons lay beyond a proper church and a place to live. Those they had.

Hit-or-Miss Ministry at Pecos For one thing, their ministry lacked continuity. Few of the friars stayed at Pecos long enough to implement a regimen, to learn the language, or to win the people's confidence. Between 1704 and 1794, the Pecos saw a constant parade of missionaries, at least fifty-eight! In the previous century, the able Andrés Juárez had lived with them for thirteen years, from 1621 to 1634. Now during the same length of time, 1721 to 1734, eleven different missionaries signed the Pecos books. Not that they were intensifying their ministry, much as they might have wished to, quite the contrary. Mostly they were ministros interinos, temporary pastors visiting from Santa Fe to provide a minimum of essential services and the sacraments, for the custody was almost always undermanned. Besides that, the superiors found themselves hard put to keep their missionaries in the field. Time and again they had to reiterate the prohibition against coming to Santa Fe without permission. Relatively speaking, Santa Fe was civilized and secure. Between Apaches and Comanches, the pueblo of Pecos was perilous and isolated. Its people, too, were dying off. The population dropped steadily, from perhaps seven or eight hundred early in the century to a mere ninety-eight adults and forty-four children in 1792. [11] Despite their beautiful and spacious church, their Christian veneer, and their commitment to military and trade alliances with Spaniards, the Pecos, like most Pueblos, held tenaciously to their traditional society and religion. To them, the friars' neglect was salutary. To them, Father Domínguez' matter-of-fact acceptance of their nine kivas in 1776 was a triumph of sorts. Diego de Vargas had spared the kivas, but a couple of his successors, harking back to the anti-idolatry campaigns of the previous century, had not. Peñuela's War on Pueblo Religion Admiral don José Chacón Medina Salazar y Villaseñor, Marqués de la Peñuela, who bought the governship of New Mexico for five years and succeeded Cuervo in 1707, had declared war on kivas. To him and to Custos Juan de la Peña, they represented all that was secretive and diabolical in Pueblo paganism. Not all the friars agreed. Nevertheless, on orders from Peñuela and accompanied by Peña, Sargento mayor Juan de Ulibarrí toured the pueblos demolishing kivas and pronouncing against native dances. [12] Later, when his administration was under fire, Peñuela took testimony from the Pueblos themselves to show that they harbored no ill feelings toward him or Ulibarrí. As usual, the Spaniards put words in the Indians' mouths and then transcribed them in proper legal form. Dutifully, the Pecos delegation reported to the casas reales in Santa Fe: Juan Tind&te;eacu, governor; Felipe Chistoe, cacique; José Tuta, war captain; Agustín and Santiago, alcaldes; and Pedro Aguate, interpreter. Testifying on July 8, 1711, they affirmed that neither the royal governor nor Ulibarrí had done them any harm. Ulibarrí, who had been alcalde mayor of Pecos and Galisteo, had not come to their pueblo on the visitation ordered by Peñuela. The Pecos may have been speaking in general terms when "they stated that they did not or do not hold against him his having got rid of their kivas and prohibited the dances. They recognize first, as the Christians they are, that having rid them of said kivas, scalps, and dances was indeed a service." Those, of course, were the Spaniards' words, not the Pecos', as the next royal governor would find out soon enough. [13]

Peñuela versus the Friars Peñuela, meanwhile, found himself confronted by angry Franciscans. His ally, Custos Juan de la Peña, had died in 1710. The new prelate, Fray Juan de Tagle, a close associate of former governor Cuervo, evidently believed the charges against Peñuela lodged in Mexico City by a couple of disgruntled New Mexicans: that the governor had abused and exploited the Pueblo Indians and had usurped the trade of the province. Peñuela fought back, denouncing Father Tagle to the Franciscan commissary general in the bitterest terms. Not only had the prelate prejudiced the Indians against the governor so thoroughly that they no longer heeded his orders, but he had also encouraged the missionaries to disobey their king. In his scandalous effort to win the Indians' allegiance, Tagle had traveled from pueblo to pueblo inciting them to dance. Worse, Fray Francisco Brotóns, one of the custos' cohorts later accused of soliciting sex, had allegedly urged the Taos to construct two underground kivas. These were the places, Peñuela reminded the Father Commissary, where the Pueblos carried on their infernal idolatry, "where they commit sundry offenses against God Our Lord, performing in them superstitious dances most inconsistent with Our Holy Catholic Faith, from which have resulted diverse witchcraft and things most improper." Despite the governor's general demolition of these kivas, with the full cooperation of the deceased custos, Father Tagle now tolerated every abuse. As a result, the Indians were getting out of hand. In this fight, which divided friars as well as laity, the Pecos sided with Peñuela. According to him, they were bitter because Custos Tagle had removed their minister, the Mexican veteran Fray Diego de Padilla, whom they liked, and had substituted a much younger man, Fray Miguel Francisco Cepeda y Arriola, who badly mistreated them. "Because of this," Peñuela continued,

Another matter rankled the governor, a shameless violation of his jurisdiction. The viceroy had forwarded to New Mexico two titles, one creating don Domingo Romero of Tesuque native governor and captain general of the Tewas, Taos, Picurís, Keres, Jémez, Ácomas, Zuñis, and all the northern and western frontiers of the province, and another granting don Felipe Chistoe of Pecos the same rank over Pecos, Tanos, Southern Tiwas, and "the frontiers and valleys of the east." Somehow, alleged Peñuela, the devious Custos Tagle had appropriated the titles, conferring Romero's because he was a partisan and withholding Chistoe's because he was not. The prelate then had the audacity to request, through his vice-custos at Santa Fe, that Governor Peñuela make the formal presentations at a ceremony before the assembled native leaders. [15] The entire weighty issue of whether or not to suppress the Pueblos' ancient customs, their kivas and dances, their way of painting and adorning themselves, their heathen attire, even their privilege of carrying Spanish weapons, came to a head during the administration of Peñuela's successor, Juan Ignacio Flores Mogollón, native of Sevilla, ex-governor of Nuevo León, an infirm, aging bachelor. The Demolition of Pecos Kivas Hardly had Flores been in office a year when he learned that the Pecos had built a partially subterranean room outside the pueblo "under the pretext of the women getting together to spin." It was a kiva, he knew. And they had others. Emboldened by the precedent of Peñuela, the resolute Flores decided on his own to obliterate this evil once and for all. On January 20, 1714, he decreed the destruction of all kivas and cois. The latter were unauthorized rooms having only a roof entrance and hidden in a pueblo house block. The decree said nothing about consultation with the Franciscans. In this case, the state was acting unilaterally. First, the governor ordered his alcalde mayor of Pecos, Capt. Alfonso Rael de Aguilar, prominent soldier and citizen of New Mexico since the reconquest, to go at once to that pueblo and investigate. If the reports were true, he was to make the Pecos raze the abominable structures,

Moreover, Rael was to have Pecos Gov. Felipe Chistoe and Lt. Gov. Juan Diego el Guijo appear in Santa Fe before Flores to explain their negligence in this matter. The decree was routed to all the alcaldes mayores

Alcalde mayor Rael carried out his governor's orders to the letter. His account, of particular interest to archaeologists today, follows in full.

Felipe Chistoe cannot have watched the rape of his peoples' sacred places without regret. But he said nothing. Life would go on. They would build new kivas. This vicious act by the Spaniards did not justify war or flight. Chistoe and the Pecos had too much to lose. The Spaniards had made him what he was, the most important Pueblo leader on the eastern frontier. They led the campaigns in which he and his auxiliaries profited from booty. And of course they supplied many of the trade goods that lured the plains peoples to Pecos every year. Life would go on. Some of the missionaries may not have been so sure of that as Chistoe. Time had not yet erased the memory of 1680 and 1696. Surely God in his wisdom and grace was enlightening the Pueblos. There were signs. Why provoke them with direct attacks on their customs, so long as these did not obstruct the preaching of the Gospel? Of course not all the missionaries could agree on what constituted an affront to God and what did not.

Other Christian Reforms Governor Flores was not through yet. The Pueblos had permitted the destruction of their kivas. Why not proceed with other Christian reforms? Why not disarm them of all but their native weapons; why not curtail their intercourse with known hostiles; why not forbid them to paint themselves and dress like heathens? They should instead be made to dress like Christians so everyone could distinguish them from the enemy. This time, Flores would ask for opinions not only from soldiers but also from friars. After all, he did not have to heed them. Regarding the weapons, it had come to his attention that the Pueblos "possessed many firearms, swords, and cutlasses." Not only did these pose a threat in case of rebellion, but too often they found their way into the hands of heathens. The civil and military men were agreed. At a junta held in Santa Fe on July 6, 1714, they urged that the Pueblos be disarmed quickly before they had a chance to hide their weapons. The friars disagreed. While the royal ordinances forbidding Indians the use of Spanish weapons should indeed be enforced in most places, beleaguered New Mexico was different. Here, they argued, where distances were great and Spanish troops few, the Christian Indians needed such weapons to defend themselves. Moreover, if the governor tried to remove them, he might touch off a new Pueblo revolt. Why not let the viceroy decide? "Believing that there was no cause for such fear," as he put it, Flores forged ahead. The alcalde mayor of each district was told to gather up the weapons without delay, while the dispossessed owners reported to Santa Fe for a compensatory payment. The penalties for failure to comply were stiff: for Spaniards who sold weapons to the Indians, fifty pesos and four years on the Zuñi frontier for the first offense, and for the second, a hundred pesos and ten years at Pensacola; for mulattos and mestizos two hundred lashes and two years on an ore crusher; and for Indians caught again with Spanish weapons, loss of those weapons without compensation, fifty lashes, and sale to a sweatshop.

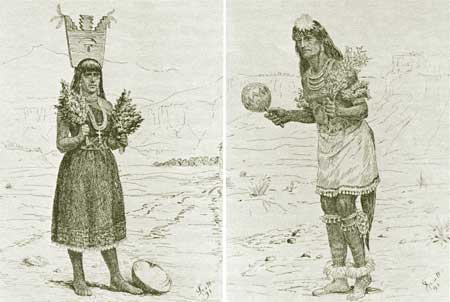

Disarming the Pueblos Again they began at Pecos, where eight muskets and a carbine were seized. One of them belonged to don Felipe Chistoe, and that was a problem. Not only did this Indian, because of his outstanding record of loyalty, possess a patent from the former viceroy Conde de Galve licensing him to carry such arms, but he also had a letter from the current viceroy conferring on him the perpetual governorship of Pecos and on his right-hand man, Juan Tindé, the perpetual lieutenant governorship. Wisely, Flores made an exception. He paid the other Pecos, but he returned the gun to don Felipe Chistoe. [19] Having voted to disarm the Pueblos, the same junta of July 6 considered the related problem of native dress and adornment. These Indians still painted themselves with "earths of different colors" and wore feathers as well as skin caps, necklaces, and earrings as they had before their conversion. What bothered the governor and the military men was not so much that these practices were offensive to God, but rather that they were being used as a cover for illicit activities on the part of the Pueblos. If Christian natives dressed like heathens, how could anyone tell friends from foes? Capt. Juan García de la Riva, like most of the others, believed that the Pueblos should not be allowed to go about looking like heathens, but he added that he had heard it said that in the winter they painted their faces with red ochre to protect their eyes from the glare of the snow. Veteran Capt. Tomás López Olguín was against the Pueblos painting themselves or entering church with feathers on their heads or ears. "It is an open abuse, like the kivas were." Moreover, said López Olguín, the Pueblos, in the guise of heathens, were stealing stock. He gave an example. A mule from the rancho of El Torreón had turned up at Pecos with the brand altered, "a thing the Apaches are not accustomed to do." When accused of stealing such animals the Pecos denied it, saying that they bought them from the Plains Apaches. That, López Olguín declared, was a lie. The Apaches came to Pecos to buy animals not sell them. And lastly, "he had heard it said that these Pecos have come in the company of Apaches to kill in the area upriver from this villa."

An Expression of Tolerance Because of the gravity of the issue, Custos Tagle requested the opinions of the missionaries in the field. Two of them agreed with the governor, others maintained that the Pueblos were being falsely accused. Fray Antonio Aparicio of Pecos refused to comment, recommending only that such a serious matter be referred to the viceroy for a decision. Some expressed their fear of Pueblo unrest if the Spaniards tried to curtail such ancient and relatively innocuous practices. After all, wrote Fray Antonio de Miranda from Ácoma, "there are many incongruous customs among us and completely permitted." Spanish women painted their faces and Spanish men wore "ribbons, plumes, and other profane dress." This time Governor Flores listened to the friars. [20] "I have come to realize," he confessed to the viceroy, "that to make the Indians change their dress would be for them more lamentable than having removed their kivas and weapons." As a result, he decided not to act until he had word from the viceroy. In Mexico City, too, they listened to the friars. A top-level junta recommended that the viceroy order the governor of New Mexico not to make any sudden moves, rather gradually by "good and gentle measures" to wean the Pueblos from their traditional dress and customs "to a civil and Christian life, without using force or violence." [21] Governors Peñuela and Flores were the last to mount concerted attacks on Pueblo culture. Succeeding governors interested themselves in the natives as an exploitable resource and as allies against the quickening raids of the nomads. Except for an occasional unusually zealous or idealistic friar, the missionaries too adopted a more patient and tolerant attitude. Commenting on these early attempts to crush Pueblo "superstition and idolatry," Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante admitted in the late 1770s "that afterward, despite various measures taken at different times by governors and prelates to extinguish these dances and kivas, the same Indians have reestablished them little by little and they maintain them to day." [22] It had come to a calculated, practical coexistence. Responding in 1714, Fray Antonio de Miranda, the veteran missionary at Ácoma, had summed up in these words the prevailing attitude of the eighteenth century.

Governors and Friars Renew Competition In the eighteenth century, as in the seventeenth, the Pueblo Indians remained for the royal governor and his alcaldes mayores, and for the friars, New Mexico's most readily exploitable resource. Naturally, a governor who had paid exorbitantly for the office expected an exorbitant return. But with no mines, no cochineal, no customs houses, such a return was by no means assured. By default, therefore, Pueblo Indian weaving, buffalo hides, and the soft tanned animal skin became "the principal object and attraction of the governors. They are," in the words of Fray Andrés Varo, "the rich mines of this kingdom." [24] To hear the missionaries tell it, the governors were avaricious, cruel, tyrannical brutes utterly devoid of scruples or a sense of duty. Rather than nurture or protect the Pueblos, they exploited them mercilessly, exacting their goods, their labor, even their women, while neglecting both the administration and the defense of this unhappy kingdom. Obviously they hated and maligned the Franciscans who called them down. To hear the governors tell it, the missionaries were the ones who forced the Indians to labor without pay, who appropriated their maize, and who entered into trading ventures while neglecting their spiritual obligations. After more than a century, their critics pointed out, the friars still did not know the Pueblo languages; after more than a century, the Pueblos still had to confess through interpreters. Regardless of who were the worse oppressors, governors or missionaries, both parties in their ardor seemed to agree that the Pueblos were indeed oppressed. But how badly is difficult to say. Certainly for don Felipe Chistoe and don Juan Tindé, with their titles, their fancy ceremonial Spanish dress, their privileges, and their influence over native auxiliary troops and native trade, both in constant demand by the Spaniards, life was not all that miserable. Nor were the Pueblos slow to take advantage of a fight between Spaniards, to play one set of "protectors" off against the other. When it suited their purpose, or there was no other way, they asserted whatever a particular governor or custos wanted to hear. No, answered Chistoe and Tind^eacute; in 1711, Governor Peñuela had never taken advantage of them. He had never summoned the Pecos all at once to work on the churches, the governor's palace, or the other public buildings in Santa Fe "but rather thirty, twenty-five, twenty, or six have gone." He had always fed them and paid them well in trade knives or awls for their carpentry and other work. [25] Yet, a dozen years later, when local politics dictated, the same two Pecos, Chistoe and Tindé, pressed their claims against a domineering governor. Judicial Review as a Check on the Governors The residencia, or judicial review of every governor's administration upon leaving office, offered the Pueblos a means of expressing their grievances, that is, when the residencia judge was impartial, unbribed, or an enemy of the departing executive. In the case of the controversial, rags-to-riches opportunist don Félix Martínez, whose residencia was held belatedly in 1723, there were Spaniards, including the aging Pecos alcalde mayor Alfonso Rael de Aguilar, who for one reason or another wanted the Indians to speak up. The Pecos demanded compensation from Martínez for the personal labor that had caused them to lose their crops, payment for two thousand boards he ordered them to cut, dress, and haul to "his palace or houses he built," and two horses, the agreed-upon price, owed to Chistoe for an Indian boy acquired from heathens and sold to Martínez. In this case, the judge ordered Martínez to pay. [26] The Pecos Present Claims Another opportunity for the Pueblos to be heard was the royal governor's general visitation, provided of course that their grievances were not against him or his partisans. The self-serving Antonio de Valverde y Cosío, who, like his rival Martínez, had risen through the ranks since the reconquest, reined up at Pecos with his retinue in August 1719. Alcalde mayor Rael had announced in July the upcoming visit. All gathered in "the casas reales," or casa de comunidad, a building seventy feet or so west of the convento. This structure, like similar ones built and maintained by the Indians in other pueblos, was a visible reminder that the Pecos were vassals of the Spanish king. Here the alcalde mayor or his deputy took lodging and sometimes resided. Here, too, travelers who stopped at the pueblo could expect room, board, and feed for their animals, as did the first bishop to visit Pecos in defiance of the Franciscans. On the doors of the casa reales were posted the decrees of the royal governor, and here, on his visitation, the governor reiterated to the Pecos the desire of their king that they receive the benefit of his justice. If anyone had injured or offended them or owed them a debt, they should step forward and so state. [27] While the account of Valverde's visitation says only that the Pecos filed "several claims" which the governor ordered "promptly and faithfully settled in full," the records of other visitations are much more explicit. By listening at the door of the casas reales to the claims presented by Pecos carpenters and traders, one glimpses the day-to-day intercourse between these Indians and their neighbors. Before Gov. Gervasio Cruzat y Góngora on July 28, 1733,

Twelve years later in the casas reales, Gov. Joaquín Codallos y Rabal sat in judgment of other small claims, all of which he allowed and ordered paid.

In conclusion, Governor Codallos exhorted the Pecos through an interpreter, in the prescribed form, to respect royal justice and decent living, as well as their missionary, and

The Pecos recognized the irony in these rhetorical preachments. How were they to respect their royal governor and alcalde mayor on the one hand and their minister and the Father Custos on the other, the agents of Both Majesties, when so often they were bitterly at odds? Guided by self-interest and a will to survive, and, one suspects, sometimes intimidated or or simply confused, the mission Indians more often than not took the governor's side, even when their position roundly contradicted their missionary. Father Esquer Damns Governor Bustamante The minister at Pecos in 1731 was a fighter. Described by a fellow Franciscan as "an anvil when it comes to work," the steadfast, undaunted Fray Pedro Antonio Esquer administered not only his own mission but, whenever needed, the villa of Santa Fe as well. He had first signed the Pecos books on February 24, 1731, when he baptized three infants. Little over three months later, there occurred an event which Father Esquer had been awaiting eagerly: the residencia of the venal, blaspheming, immoral Gov. Juan Domingo de Bustamante. Given the opportunity, the Pecos missionary unburdened his conscience with gusto.

In a lengthy and impassioned indictment, during the course of which he warned the residencia judge that Bustamante had planted spies in his house, Esquer charged the governor with extorting, tyrannizing, intimidating, and perverting soldiers, citizens, and Indians. He told how Bustamante had been trained in corruption by ex-governor Valverde, his uncle and father-in-law, originally a poor man who had risen to wealth by cheating the soldiers and Indians of El Paso and who, by connivance, had secured the governorship of New Mexico. To cover his muddy tracks, Valverde had bought the governorship for his nephew for twenty thousand pesos. After nine years and two months in office, Bustamante, Esquer alleged, "now has some 200,000 pesos, rather more than less, and is the owner of wrought silver, coach, slaves, fine clothes, household furniture, pack train with not a few draft mules, and not a few horses." In the friar's opinion, Bustamante was an irreverent ogre without a single redeeming grace. "We can indeed say in Catholic truth that we have suffered martyrdom during the time of his administration." Esquer labeled the governor's subordinates "fruit of the same tree." They corrupted the Indians, teaching them to lie and be deceitful, even to one another. This was dangerous, for even Indians could recognize the many injustices that lay so heavy on the land, and in such recognition grew the seeds of revolt. "As a result," the Pecos friar confessed, "we suffer torment beneath the death-dealing club for the truths inherent in the Holy Gospel, because the Indians live like Moors without a lord, serving only the alcaldes mayores, who deny them a fair wage, restrain them from doing good, and supply them with lies and evil." [31] Maybe he was right. Maybe the Pecos were cowed. Whatever their reasons, they lauded Governor Bustamante. Testifying at his residencia, Antonio Sidepovi, indio principal and governor, pled ignorance of any wrongdoing on Bustamante's part and agreed that the royal governor had acted as a protective father to the people of Pecos. He had bought their maize when no one else would, and he had paid them in "mattocks, axes, plowshares, and other tools." He had helped the pueblo progress, nurtured the Faith, and defended the Pecos from their enemies. In fact, Governor Bustamante, his alcaldes mayores for Pecos and Galisteo, who were Alfonso Rael de Aguilar and Manuel Tenorio de Alba, and all his other officials had "administered justice with complete fairness, without being brought gifts or bribes, and they had treated the people of his pueblo well with complete love and affection." [32]

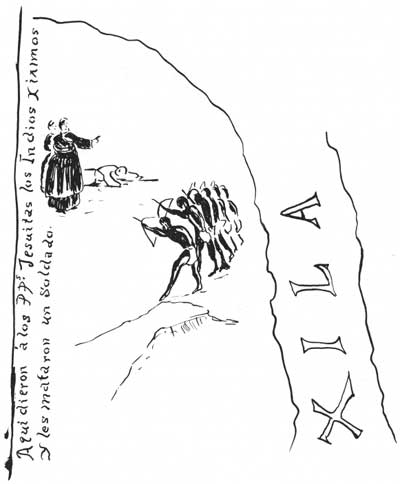

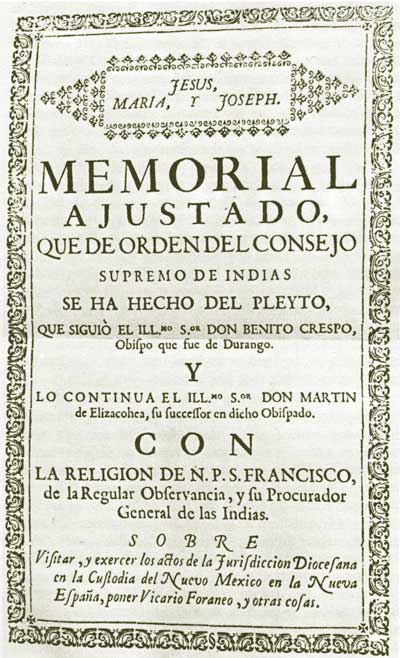

In taking the governor's side, the Pecos acknowledged who could do them the most good, and the most harm. Their missionaires' influence had begun to wane. In the lives of the Pecos, the alcaldes mayores, minions of the governors, offered more continuity. Some of them served a decade or longer. Most were native-born New Mexicans. They were the ones who regulated trade and sounded the call for native auxiliaries. In the eighteenth century, the casas reales had replaced the convento as the focus of Spanish influence at Pecos. New Mexico Visited by Bishop Crespo By 1731, the Franciscans of New Mexico were very much on the defensive. It was difficult enough coexisting with the likes of Juan Domingo de Bustamante, but at least governors came and went. Now a challenge of more lasting consequence faced them. After two centuries of nominal jurisdiction, the bishop of Durango had begun to press with vigor his claim to New Mexico. In 1725, Bishop Benito Crespo had gotten as far north as El Paso on an episcopal visitation. Five years later—at the invitation of Governor Bustamante—he came again and insisted on proceeding up the Rio Grande, the first bishop ever to do so. It was a warm day in July 1730. As His Most Illustrious Lordship don Benito, twelfth bishop of Durango, approached the pueblo of Pecos attended by his entourage, Fray Juan George del Pino hid upstairs in the convento. The bishop's secretary rode on in advance. When he noticed the bishop's cook standing outside the convento, he yelled at him to get away from there and go to the casa de comunidad. "Under no circumstances did His Most Illustrious Lordship wish to stop or to dine in the convento." At that, Father Pino leaned out of the mirador and offered the convento, saying that all was ready. He had made no preparations in the casa de comunidad. He would of course comply most willingly with the decision of His Most Illustrious Lordship. Just then, he caught sight of the bishop's party coming up the trail. Alerting the convento servants as he went, the friar rushed downstairs, through the convento, and into the church to receive the bishop at the church door. Solicitous to show all due respect, but not subordination, Father Pino welcomed the eminent visitor, begging earnestly that he deign to accept the hospitality of the convento where a meal was waiting. The prelate responded graciously but firmly. He would accept the meal, but not in the convento. "With that, he took his leave of the Father, who afterward ordered that the food be transferred to said casa de comunidad." [33] The nice maneuvering that day at Pecos by bishop and friar was no game. Outspoken Custos Andrés Varo, on orders from his superiors in Mexico City, maintained steadfastly that the custody was not subject to the episcopal authority of the Durango see. Just as steadfastly, Bishop Crespo maintained that it was. The two, who had met at El Paso and traveled upriver together, had negotiated a temporary compromise. The bishop would refrain from making a formal visitation of the churches, baptisteries, mission books, and the like, and he would publish no edicts. But he would be received in the churches by the friars, and he would be allowed to preach and to perform the rite of confirmation. Both men were at pains not to do or to say anything that might prejudice their cases in the future. Crespo Finds Fault with Franciscans Although he maintained his episcopal decorum throughout, Benito, bishop of Durango, found much that displeased him in Franciscan New Mexico. Writing to the viceroy from Bernalillo and El Paso, he leveled a number of serious allegations. The king, who paid forty royal allowances annually in support of these missions, had every right to expect the services of forty missionaries, yet the bishop had found seven lacking, and from what he was told, "they have been lacking for a long time." On the basis of one brief visit, he recommended consolidation, one friar for several pueblos, one for Pecos and Galisteo, one for San Juan, San Ildefonso, and Santa Clara, and so on. He charged that the friars lacked the zeal to convert the peoples who bordered on the pueblos but were content instead simply to trade with them. In the pueblos themselves, he claimed to have seen signs of paganism, idolatry, apostasy, "and the reciprocal lack of love" between missionaries and Indians.

Perhaps the bishop's most serious charge, the one he kept returning to, was that none of the missionaries knew the native languages. Not only did this demonstrate, in his opinion, a woeful lack of dedication "when the languages are not so difficult," but it also meant that the friars were aliens in their own missions. Moreover, the church's precept requiring annual confession and communion went unfullfiled in New Mexico since the Indians refused to confess "except at the point of death because they do not want to confess through an interpreter." That was not entirely fair, countered Fray Juan Antonio Sánchez. He himself knew Tewa. So did Fray José Irigoyen. Fray Pedro Diaz de Aguilar and Fray Juan José Pérez de Mirabal each knew a Pueblo language, the former Keresan and the latter Tiwa as spoken at Taos. Many others had a start learning several. That, in fact, was the problem, according to Sánchez. Every time a missionary mastered a few words of one language, the superiors transferred him somewhere else. What did they expect? Before he left the custody, Bishop Crespo appointed Santa Fean don Santiago Roybal, a secular priest he had ordained in Durango for the purpose, as his vicar and ecclesiastical judge, an act of dubious legality. He also posted a schedule of fees for marriages, burials, etc., and took one last dig at the Franciscans. The fees they had been charging were, he said, both arbitrary and exorbitant. [34]

In fairness to the friars, it should be said that the crusading Bishop Crespo was prejudiced. Like his predecessor, Pedro Tapis, he was strongly pro-Jesuit. Seven years before, he had had the sacred rites making him bishop performed in Mexico City at the Jesuit church of La Profesa. He warmly endorsed a Jesuit takeover of the apostate Hopi pueblos, and he was always, sometimes openly, sometimes by implication, comparing the Franciscan missions unfavorably with those of the Jesuits. Besides, there was more than a little truth in the friars' contention that Crespo had come to New Mexico uninvited by them, had spoken mainly with their enemies, had ignored their merits and the adverse circumstances of their ministry, and had catalogued only their faults. Still, some of what the bishop had said was true, and the Franciscans of New Mexico knew it. [35] For the next thirty years, during which the charges and countercharges varied little, the friars strained to defend themselves and the sacredness of their Order from a convenient alliance of bishops and governors and, at the same time, to put their missionary house in order. Considering the odds against them, even their limited success was a credit. They persevered. Menchero Calls for Rededication Busy, enterprising Fray Juan Miguel Menchero, preacher, censor of the Holy Office, procurator of the custody of the Conversion of St. Paul, and visitor by order of the Franciscan commissary general for New Spain, enjoyed being a superior. Sent out from Mexico in 1731, in the wake of Bishop Crespo's visitation, it was his task to marshal the friars' defense and to correct whatever abuses he found. Arriving jaded and sweaty at El Paso in early July, Fray Juan Miguel issued the usual official letter announcing his visitation. He cited his authority from the Father Commissary General and proclaimed a list of mandates. Every missionary must keep in his mission a book of expenses and income from crops and livestock. There must be no women cooks in the conventos "so as to avoid the scandal that can follow from it." Inspired by the zeal of the "old Fathers," the present friars should dedicate themselves to the upkeep and repair of their churches and conventos, "repairing drains and other things that can cause their destruction." But the crux of the letter had to do with language. First, Spanish should be taught at every mission, as the king had ordered repeatedly. Primers, catechisms, and readers should be distributed according to the number of catechumens. And second, to prevent the scandal of it being said that the friars administered confession to Indians only through interpreters, to the discredit of their holy habit,

It was a good try. None of their relatively short-term, part-time missionaries in the eighteenth century seemed to know the Towa language of the Pecos. A few of them, like Francisco de la Concepcion González, 1749-1750, and Juan José Toledo, 1750-1753, strained mightily to transliterate the difficult Pecos names, names like Extehahuotziri, Sejunpaguai, Guaguirachuro, Huozohuochiriy, and Timihuotzuguori. But if any of them attempted even a simple word list or vocabulary, it has not come to light. Before he could get on with his visitation, Father Menchero, as supply man of the custody, had to deliver the goods purchased in Mexico City for the missionaries against their annual royal allowances. Because of Bishop Crespo's allegations, Menchero was especially scrupulous in his accounting. Mission Supply The supplies for Pecos, which evidently were supposed to last three years, came to 807 pesos 4 reales, 503 on account and the remainder advanced against the 330-peso allowance for 1731. In August, missionary Pedro Antonio Esquer of Pecos checked the goods against the list in Santa Fe and signed a receipt before witnesses. It was up to him to have the stuff hauled out to Pecos. By far the most costly items, valued together at more than two hundred pesos, were two cases of fine chocolate. Other boxes, trunks, and odd bundles contained sugar, cinnamon, saffron, and other spices; olive oil, candle wax, and fine-cut tobacco; majolica, china, and pewter dishes; two habits, two cowls, a cloak, and two cords; quantities of cloth of different varieties; a ream of paper, razors, a brass wash basin, comb, mirror, and 500 bars of soap; assorted kitchen utensils, tools, bridles, needles, and pins; a set of vestments of flowered silk and a Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe; and, for the teaching of Spanish, two sets of primers, two dozen catechisms, and two dozen readers; as well as numerous other goods not readily available at the ends of the earth. [37] To begin his formal visitation, Father Menchero accompanied Esquer down to Pecos, where he found everything in accord with the dictates of the Council of Trent. In the privacy of a cell in the convento, he put to the missionary a series of questions under vow of holy obedience. Had he observed faithfully the Institute, Rule, and Constitutions of the Order? Did he administer the Holy Sacraments to Indians and Spaniards? Had Custos Varo done his duty in everything, including the distribution of the tithes to the poor? To everything Esquer answered yes. [38]

Back in Santa Fe after visiting several of the missions, Menchero paused to address "certain things worthy of attention." Henceforth, no missionary was to order Indians to work outside the mission "unless payment is made to them in advance." No friar was to charge an Indian any fee whatsoever for administering the sacraments. Considering "the malice and passion that reigns in this kingdom," he must not accept anything, under any circumstances, even if offered freely. For the sake of decency and cleanliness, Menchero appealed to them to get the nests of swallows out of their churches. Any friar who showed up in Santa Fe without permission of the vice custos and good reason would be subject to six months at the mission of Zuñi for the first offense, and for subsequent offenses, arrest by "the secular arm" and summons before the custos.

Lastly, he pleaded with the friars to get along with government officials. If an alcalde mayor did something "contrary to the service of God, the welfare of the Indians, and the will of the Catholic Majesty"—like forcing them to herd stock in various places without pay—the missionaries were to try prudent and fraternal persuasion. If that did not work, they should report the offense to the vice-custos, who would take it up with the governor. "From the unity of Your Reverences with the great zeal of His Lordship," quoth Menchero rhetorically, "better service to Both Majesties is bound to result." [39] He might as well have been beating his head against an adobe wall. Bishop Elizacoechea at Pecos As for bishops, another soon came visiting, despite the unsettled question of his legal right to do so. This time, the friars backed down. Crespo's successor, Doctor don Martín de Elizacocchea, "bishop of Durango, the kingdom of Nueva Vizcaya, its confines, and the provinces of New Mexico, Tarahumara, Sonora, Sinaloa, Pimas, and Moqui, of His Majesty's council, etc.," rode up to Pecos with his Basque suite late in August of 1737. He was permitted free access to the church, the mission books, and everything else. "Having inspected the church of said pueblo," read the note in the Pecos book of baptisms, "its baptismal font, oils and holy chrism, the sacristy, vestments, altar stone and altar, and having said the responsories in the form prescribed by the Roman Ritual, he declared that everything was appropriately decent and according to law." He expressed his thanks to Pecos missionary Fray Diego Arias de Espinosa de los Monteros and encouraged him to continue the good work. He included no admonition to learn Towa. Whether the bishop spent the night in the convento or in the casas reales, the note did not say. [40] In the twenty-three years that elapsed between Elizacoechea's visitation and that of a successor, the friars came to see bishops as the lesser of two evils. The governors were their real scourge.

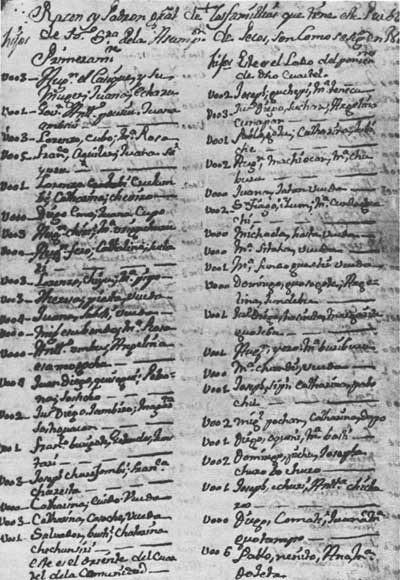

Apostles to the Hopi and Navajo While neglecting Pecos, where the Comanches began to make themselves felt in the late 1730s, the Franciscans directed their apostolic labors to the west. Old Fray Carlos Delgado went out to the apostate Hopi pueblos in 1742 and led back a migration of hundreds of refugees, mostly descendants of the Tiwas who had fled during the 1680s. He also opened up the Navajo field for his brethren, claiming thousands of conversions. Later in the 1740s, the irrepressible Fray Juan Miguel Menchero picked up the initiative. These new spiritual conquests were the friars' best answer to their critics, a demonstration to the world that the missions of New Mexico were still "living vineyards of the Lord" and their missionaries true heirs of the apostles. Yet the governors opposed them, maliciously, it seemed to them. When reports by the outspoken Fray Andrés Varo reached the viceroy, he decided to send a member of his household, don Juan Antonio de Ornedal y Maza, to New Mexico to get the facts. Instead, Ordenal got together with the hot-headed, youthful Gov. Tomás Vélez Cachupín, another member of the viceroy's "family," and "hell conspired" to roast the missionaries of New Mexico as they had never been roasted before. But they did not wither. Rather they fought hellfire with hellfire. [41] Pecos Mission at Mid-Century Despite the crescendo of royal governors and missionaries having at one another, life at Pecos changed little. Every year there were fewer people. A squad of Spanish soldiers moved in west of the convento beyond the casas reales to help defend them against assault by the Comanches. Governor Codallos y Rabal petitioned the Franciscan commissary general in 1744 to remove Fray Juan José Hernández, on-again off-again minister at Pecos, because, in Codallos' words, "every day I receive pitiful complaints from the Indians because of his bad treatment of them." [42] Six years and six missionaries later, the Pecos governor and the cacique, responding through an interpreter, answered the vice-custos' questions about Fray Francisco de la Concepción González just the way they were supposed to. He was never absent from the mission. He said Mass on Sundays, he instructed them and their children daily in the catechism, and he spoke to them in Spanish "so that they might learn the language." He charged no fee for baptisms, marriages, or burials, or for celebrating the patron saint's feast, August 2. He succored the pueblo when in need. Never had he taken anything from their homes or corrals. Never had they woven mantas for him. Willingly they planted four fanegas of wheat and half a fanega of maize for his sustenance and that of four boys, a bell-ringer, a porter, a cook, and three grinding women. They also provided firewood for the convento. [43] Father González, their missionary for part of 1749 and 1750 had scars to show, figuratively speaking, from his battles with royal governors. Gaspar Domingo de Mendoza, 1739 to 1743, had accused him of complicity in the alleged native uprising plotted by one Moreau, a French immigrant later sentenced to die. As a result, the friar's superiors had recalled him to Mexico City and had subjected him to judicial inquiry. A fellow missionary, testifying in González' behalf, swore that his conduct had been exemplary, that he had always tried to keep the peace by preaching the Gospel. Moreover, he had repaired the churches and conventos of Santa Fe and Nambé and had rebuilt the Tesuque church from the foundations up, begging the means from among the citizenry and donating a large part of his own royal allowance. Acquitted and back in New Mexico, the undaunted Father González had run afoul of Governor Codallos. When the friar objected to the governor's use of some Tesuque laborers, whom Codallos allegedly had taken away from catechism and church construction and then had failed to pay, and when the missionary refused to perjure himself in Codallos' behalf, the governor's friendship turned to mortal hatred. He vowed to break the insubordinate friar. And in that spirit he revived the old charges. [44] But Gonzales outlasted Codallos and moved out to Pecos late in the summer of 1749. While there, he compiled the most accurate census of the pueblo to date, correcting in the process the wild guess of Custos Varo. The Pecos Census of 1750 Contrary to what Varo said, there were not as many Pecos at mid-century as there had been fifty years before, not nearly as many. Disease, emigration, and attacks by hostile Plains Indians had cut their number in half. Finding no census in the provincial archive in 1749, Varo had estimated the pueblo's population at more than a thousand. Father González counted each and every one, but he did not bother to add them up. Someone else, taking issue with Varo, noted on González' census "there are probably 300 persons here." Actually there were 449: 255 adults and 194 children. Except for Agustín, who headed the list as cacique, and Francisco Aguilar, evidently an Indian or a thoroughly accepted mixed-blood González valiantly rendered the native surnames of every adult male and nearly every woman along with his or her Christian given name. He grouped them according to where they lived, but in such a way as to drive an archaeologist up the wall. He began, it would seem, with the South Pueblo and then moved north: "east side of the community house block (cuartel de la comunidad)"

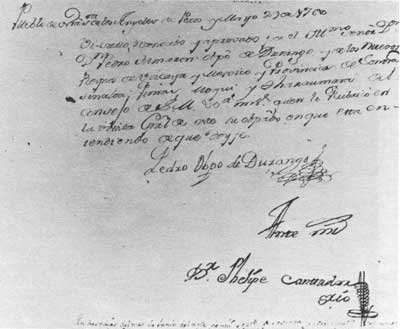

Bishop Tamarón Made Welcome During the 1750s, while the population of Pecos fell from 499 to 344, the governors kept the Franciscans pretty well muzzled. When, in 1759, a third bishop of Durango announced his intention to visit New Mexico, the friars were almost eager. They wanted to talk. This bishop, the untiring, practical, wide-eyed Dr. Pedro Tamarón y Romeral, the bluerobes made welcome, in his words, "as if they were secular priests." [46] The bishop and his suite, which included a corpulent black valet who "must have excited the Indians' imagination," rode in the company of Custos Jacobo de Castro and an armed escort over the mountain from Santa Fe to Pecos on Thursday, May 26, 1760. Despite the weight of his responsibilities, His Most Illustrious Lordship was enjoying himself. "He was one of those inveterate tourists who delight in new scenes and little-frequented places and have a flair for collecting odd bits of interesting information." [47]

The Pecos came out on horseback to meet him, performing "many tilts to show how skillful and practiced they are in riding." Fray Francisco Javier DÁvila Saavedra, a native of Florida now in his mid-forties, awaited him at the church door. Inside, Bishop Tamarón administered the sacrament of confirmation to 192 Pecos, although, as he later admitted, it caused him considerable mental anguish. The adults simply were not properly instructed. During the ceremonies, one of the principal men, Agustín Guichí, a Pecos carpenter, seemed to be studying the bishop's every move. In the course of his inspection, Tamarón charged Father DÁvila to prepare a book of confirmations so that these and subsequent ones might be legally recorded. He asked why there had been no marriage entries in more than a year. No marriages had been performed, DÁvila replied. The Language Problem With the Pecos books before him, the bishop began to lecture the friar. One thing more than any other "saddened and upset" him. It was the same thing that had dismayed Bishop Crespo thirty years before. In all these years, the friars had failed to learn the native languages or to teach the Pueblos intelligible Spanish.

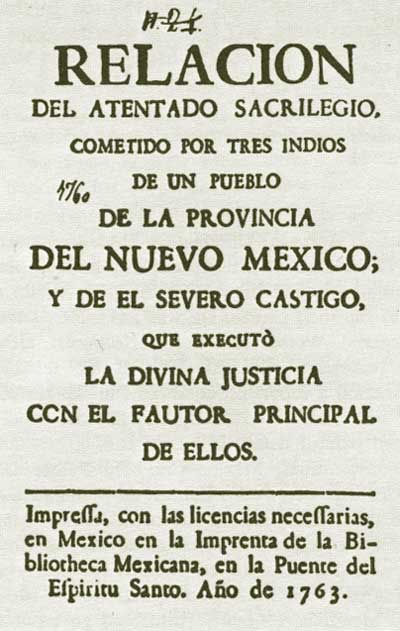

It was not only confession. The Pueblos, in the opinion of Bishop Tamarón, were woefully ignorant of the chief truths and duties of the Christian faith. They could recite in unison some of the catechism, but since they did not understand Spanish, they had no idea what they were saying. For one thing, he ordered Father DÁvila to give up the current practice of having the native fiscales, or catechists, lead the Pecos in group recitations. Rather, each individual should be examined separately. Again language was the key. Interpreters, who only added to the confusion, were not the answer. The friars simply had to come to grips with the Pueblo languages. He commanded them to. He begged them to. He offered to pay the printing costs of native-language catechisms and guides to confession. Still, after repeated and vehement admonitions, the custos and missionaries "tried to excuse themselves by claiming that they could not learn those languages." It was, to be sure, the friars' most glaring failure in New Mexico, and some of them admitted it. But it was not all their fault. The Pueblos had learned by the eighteenth century that the surest defense of their traditional culture was to guard their languages. By refusing to surrender this key to their closed Pueblo world, they not only blocked Christian invasion but they insured as well its quiet permanence. Those few friars who did learn a Pueblo language in the eighteenth century did so most often at Zuñi or one of the other western pueblos where the people were not so much under the eye of the Spaniards and not so secretive. In utter frustration, Castro related to Bishop Tamarón how his friars were thwarted by Pueblo interpreters who seemed to be deliberately confusing them or by "the rebelliousness of the people." The bishop himself had admitted that in matters of trade and profit "the Indians and Spaniards of New Mexico understand one another completely," Yet when it came to the catechism, the Pueblos were ignorant. [48] That was no accident. The Spaniards' Christian zeal, diluted in eighteenth-century New Mexico, was no longer a match for the reinforced tenacity of the Pueblos. A Memorable Burlesque at Pecos Three months after Bishop Tamarón's visitation, there occurred at Pecos one of the most delightful events in the annals of New Mexico's past, at least when viewed from the twentieth century. The bishop had an account of it published to illustrate the marvelous workings of Christian divine retribution. It also said something about the Pecos after a century and a half of domination by Both Majesties, after assaults by smallpox and Comanches, after the violence of their own discord, and after the reduction of their people by eight of every ten. Their spirit had not broken. It was mid-September, about harvest time. They must have been feeling glad. There were a few soldiers on escort duty at the mission, but the missionary was probably off in Santa Fe. The Pueblos had long featured "sacred clowns" in their ceremonials, clowns who, unlike the rest of the people, could ridicule even the supernaturals. Why not ridicule a bishop?

Agustín confessed his terrible sin, through interpreter Lorenzo, to Fray Joaquín Rodríguez de Jerez, who afterward administered extreme unction. Then he died. The friar interred his mutilated body on September 21 in the Pecos church. [49] Fiscal Juan Domingo Tarizari testified that he had examined the bear's tracks. It had come straight down out of the sierra, had mauled Agustín, and had gone back without even entering the milpas to eat maize. This was strange behavior for a bear. A bear simply did not attack a man unless the man was chasing the bear. To Bishop Tamarón, the message was clear.

The Decline of Pecos In the generation after Agustín's memorable burlesque, the gods, both Christian and Pueblo, frowned on Pecos. Not that it was all smallpox, Comanches, famine, and death, but the Four Horsemen did gallop through these years with devastating clatter. Immersed in their own problems, not the least of which was manpower, the Franciscans neglected Pecos more and more, to the point in the 1770s and 1780s that they expected the people to come up to Santa Fe for baptism and marriage. The statistics, devoid though they are of human pathos, of the whimper of a dying child, chart the pueblo's unrelenting downward course.

Before he was through with his thankless assignment, Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez, chosen comisario visitador in 1775 because of his capacity for incisive observation, his meticulousness, and his candid integrity, would cause his superiors to rue their choice. He was too incisive, too meticulous, too candid. Worse, he was a perfectionist, although not without a redeeming wit and sense of the ridiculous. The superiors wanted a report on conditions in the custody, which they knew were bad, but evidently they had not expected to be told, in such painful detail, just how bad. The conscientious, Mexico City-bred Father Domínguez hit it off with Col. don Pedro Fermín de Mendinueta, a native of Navarre thirty-five years in the royal service. Mendinueta, who reflected the heightened attention to duty of Charles III's bureaucracy, had governed New Mexico for nearly a decade. In the spring of 1776, while Domínguez and his two companions shared Mendinueta's table, visitor and governor talked.

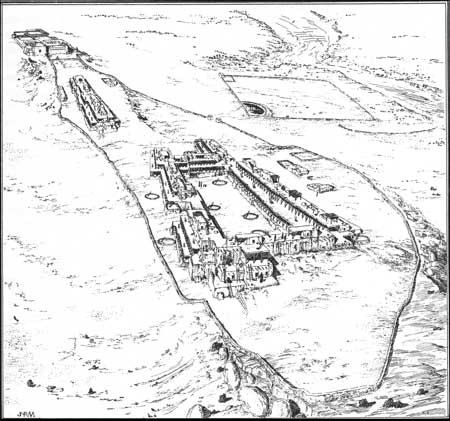

Franciscan Neglect of Pecos "In the private conversations we two had during those days," Domínguez reported to his provincial, "he asked me for a friar for the Pecos mission, giving me good reasons, among them the long time those souls have gone without spiritual nourishment." The visitor agreed and at once assigned one of his companions, the youthful Fray José Maríano Rosete y Peralta. But just as Rosete was leaving, a letter arrived from Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante of Zuñi. Vélez, who would join Domínguez that summer in an attempt to reach Alta California by striking northwestward from Santa Fe, asked that Rosete be named assistant at Zuñi. The visitor consented, and "the mission of Pecos remained as before." It was as if the friars of Santa Fe, who were supposed to be looking after Pecos, along with Galisteo and Tesuque, had forgotten the mission existed. During 1767 and 1768, Mendinueta's first two years in New Mexico, they had celebrated twenty-one baptisms for the Pecos, but since then only fifteen in seven years. During his entire tenure to date, nine years, they had entered in the Pecos books only two marriages and seven burials. "The lord governor deplores this," Domínguez continued, "but he is satisfied with the reasons I have given him to persuade him that not everything can be as we should like." Mendinueta was satisfied but not satisfied. When the Father Visitor began to speak and gesture earnestly of explorations north and west from New Mexico, and of all the heathen peoples crying out for baptism, the governor stopped him cold with a question. "If there are not enough fathers for those already conquered, how can there be any for those that may be newly conquered?" It was a good question, one calculated, in Domínguez' words, to "chill a spirit ardently burning to win souls." [51] The Meticulous Visitation of Domínguez In late May or early June 1776—as sweat ran down the necks of delegates to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, two thousand miles away—Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez conducted his visitation at Pecos, the most thorough ever. He began with a brief description of the physical setting.

He moved on next to the meticulous portrayal, paraphrased earlier in this chapter, of church and convento. He did not bother with the casas reales, saying only that a former alcalde mayor, Vicente Armijo, had taken the balusters from the western mirador of the convento and put them in the casas reales. [52] To feed the missionary, when they had one, and his convento staff, the Pecos tended five pieces of ground: a "beautiful" walled vegetable garden abutting the cemetery on the west and four large milpas north, west, and south of the kitchen garden not more than a quarter-league away. They would not tell him what the yield was. Instead, "they do say uproariously that wheat, maize, etc., are sown, except for chile, and that a sufficient amount is harvested." Since there was no missionary, they had planted these field for themselves. The Pueblo in 1776 As for the pueblo itself, the only entrance through the long low peripheral wall from the outside, said Domínguez, was a gate facing north.

By comparing Domínguez' word picture, as sketchy as it is, with the house blocks Father González listed in his 1750 census, and with the maps of A. V. Kidder's excavations, it is possible to correlate the lot. The two wide "tenements" on the east and the west of Domínguez are the "east side of plaza house block" and "plaza" of González, that is, the east and west sides of Kidder's main Pecos "quadrangle." The entrance midway along the east side, cited by Domínguez, shows clearly on the maps of Kidder. The third of Domínguez' "four tenements," which he did not describe, probably because it was a less impressive extension of the first two, is the "placita" of González and the U-shaped extremity at the south end of Kidder's quadrangle. The Domínguez tenement that "stands alone and is very long, extending from north to south" would seem to be the "community house block" of González and the mysterious "south pueblo" of Kidder. From the vantage of a hawk circling high over the elongated mesilla of Pecos in 1776, one would have seen the main pueblo complex at the northern tip, the long thin south pueblo in the middle, and the mission compound at the southern end. The two pueblos, evidently both occupied when Alfonso Rael de Aguilar destroyed the kiva halfway between them in 1714, had continued to house the Pecos through most of the eighteenth century, even though the people's diminishing numbers would have permitted consolidation in one or the other. [55] Father Domínguez counted one hundred "families" at Pecos, or 269 persons. Their language, he observed, was one with Jémez. "It is very different from all the other languages of these regions, and its pronunciation is closed, almost through clenched teeth." Rather matter-of-factly, and without commentary, he added that the Pecos spoke Spanish "very badly." Availing themselves of wood from the sierra, most of them were good carpenters.

The Pecos as Christians Regarding their observance of the Christian faith, Domínguez, surprisingly enough, deemed the Pecos "devout and well inclined," which hardly squares with what he had to say later about the Pueblos in general. Alcalde mayor José Herrera assured the visitor that even though the Pecos had no missionary, they understood that their children "must go to the church daily to recite the catechism with the fiscal." On Saturday mornings and on feast days, everyone went to say the rosary. For baptisms and marriages, they journeyed up to Santa Fe where the friars would keep the Pecos books until a missionary returned to their pueblo. "With regard to burials," Domínguez noted, "if an Indian dies, the others perform the offices, etc." Devout or not, the Pecos were in a bad way. Comanche raiding had forced them to give up their irrigated fields northeast of the pueblo along the Pecos River. Out of fear of this enemy, they no longer hauled the good water half a league up from the river, where swam, according to Domínguez, "many delicious trout." They relied instead on "some wells of reasonably good water below the rock." Even arable land dependent on rain, if it lay at a distance from the pueblo, was too dangerous to work.

Governor Mendinueta had given them a dozen cows, which, taken with the eight the Comanches had left them, brought their herd to twenty. Once the Pecos had been rich in horses. Now they had twelve in all, "sorry nags" Domínguez called them. "Today these poor people are in puribus, fugitives from their homes, absent from their families, selling those trifles they once bought to make themselves decent, on foot, etc." [56] Back in Santa Fe, Domínguez filled in briefly as minister of the villa, and thus as missionary of Pecos in absentia. In mid-June, he had a new book of baptisms begun for Pecos and on July 23, six days before he and Father Vélez de Escalante set out on their "splendid wayfaring" into the Great Basin, he made the first entry. Domingo Aguilar, of the prominent Pecos Aguilar clan, and his wife María Rosa had appeared at the church door in Santa Fe carrying a three-month-old son. Why had they delayed so long, the Padre inquired. They had been away from their pueblo, they told him, "looking for something to eat." [57] Dominquez Characterizes His Brethren The actions of some of his brethren had scandalized Father Domínguez, probably more than they should have. When he listed for his superiors all twenty-nine friars resident in the custody, including himself, he made no comment about thirteen who apparently were doing their job. Eight he classified as old and ill, or just ill, and one as blind. Two were drunks. Another, he alleged, lived openly with a married woman and another was an unruly, brawling trader "at the cost of the Indians' sweat." One each he characterized as "ungovernable and living in scandal," "not at all obedient to rule and a trader with heathens," and "not at all obedient to rule and an agitator of Indians." [58] The timely advent of forty-six friar recruits from Spain aboard the warship El Rosario in 1778, enabled the superiors to dispatch seventeen new men to the custody straight-away. Replacing the ailing and the unsuited, they brought the total to thirty-five, "leaving three as extras on hand to fill vacancies as has been customary." A neat listing, drawn up soon after, matching men and missions showed Fray José Manuel Martínez de la Vega at Pecos. If he really served there, it was only on the fly, and he baptized no one. He was soon at Albuquerque. Fray José Palacio, who signed himself "ministro de esta misión de Pecos," celebrated one baptism at the pueblo in 1779 and three in 1780. He may even have been resident for a time. [59] Then, unexpectedly, the smallpox hit, carrying off so many people that the royal governor urged reducing the number of missions. Smallpox Ravages the Province The toll was ghastly. At Santo Domingo in February and the first week of March 1781, at least 230 Indians died. Up and down the river the count at several pueblos exceeded a hundred. The plague spread. Evidently many died at Pecos, but the burial records are lost. [60] Two censuses of the eastern pueblo, one before and one after, tell the tale: 1779 94 men, 94 women, 23 boys, 24 girls, or 235 persons Reporting on May 1, 1781, the governor put the total number of men, women, and children dead in the contagion of 1780-1781, probably the worst ever, at 5,025, a quarter or more of the entire population. Under these circumstances, why, the governor asked, should not some of the desolated missions be joined together and the total number subsidized by the crown reduced proportionately, say to twenty. Consolidation of Missions Ever since the visitation of Bishop Crespo in 1730, consolidation had been a dirty word with the missionares of New Mexico. Now the governor, the highly touted, economy-minded, military hero Juan Bautista de Anza, had them against the wall. His superior, the Caballero de Croix, first commandant general of the Provincias Internas and vice-patron of the church in this recently formed northern jurisdiction, liked the idea. No matter that the friars protested. Croix cut their missions to twenty. [61]

In the case of Pecos, consolidation was merely a clerical matter. For the previous two decades, while maintaining the status of a mission and thus its claim to a full-time missionary supported by royal allowance, Pecos had been treated in effect as a visita, or preaching station, of Santa Fe. Since the stipend went to the man and not to the mission, as was confirmed several times in the 1780s, it was up to the custos to place his men wherever he thought they would do the most good. By formally attaching Pecos to Santa Fe as a visita in 1782, consolidation simply acknowledged a fact of long standing. Given the hard times, Pecos, with its steadily declining native population and no nearby Hispanic communities, no longer warranted the services of a full-time minister. It worked as before. To regularize certain human relations in the eyes of the church, Fray Francisco de Hozio, minister at Santa Fe and "pro ministro" of Pecos, ordered chief catechist Lorenzo to bring all the people who needed marrying up to the villa. Ten Pecos couples showed and, on January 4, 1782, in mid-winter, all were duly married. Three weeks later, Custos Juan Bermejo, who also served as chaplain of the Santa Fe presidio, rode over to Pecos with a military escort to baptize two new babies. Soldiers stood as godfathers, and the friar signed as custos and pro ministro of Pecos "for lack of a minister." While he was there, Bermejo married one more couple and, at a nuptial Mass, veiled all ten previously joined in Santa Fe on the fourth. [62]