Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Escalante as Historical Researcher During the last quarter of the enlightened eighteenth century, when the Spanish crown's pragmatic interest in history and geography pervaded every corner of her vast and vulnerable empire, an intense young Franciscan received permission from the governor in Santa Fe to examine the provincial archives. This was a collection which, in the governor's estimation, "contained nothing but old fragments." Undaunted, Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, not yet thirty but already in failing health, spent hours poring over, copying, and abstracting what documents he could. Among those from the period of the great revolt, he came across a formal complaint by the Santa Fe municipal council against Gov. Antonio de Otermín. Not only did this document present a different version of the outbreak, notably at variance with Otermín's own account, but it also suggested that the Indians of Pecos were their own worst enemies. [1]

Revolt Laid to Governor Otermín The cabildo put the blame for the revolt of 1680 squarely on Governor Otermín. Because he was either unable or unwilling to govern, or both, Otermín relegated all authority to his secretary of government and war, Maese de campo Francisco Javier, "a man of bad faith, avaricious and sly." Well built, with very gray hair and the scar of an old wound across the left side of his forehead, the cruel Javier had driven the Indians of New Mexico, in the words of the cabildo, "to the ultimate exasperation." A short while before the general uprising, Javier had seized at the pueblo of Pecos a camp of Apaches to whom he had given assurance of safe-conduct. Coolly, he distributed some of these captives to his friends and shipped the rest off to Parral for sale. To the Pecos, who gained much of their livelihood from trade with Apaches, the treacherous act of Francisco Javier was grounds for rebellion, or so Fray Silvestre implies. Yet, in the very next sentence without the least explanation, he tells how the Pecos—or the pro-Spanish faction at Pecos—warned Maese de campo Francisco Gómez Robledo of the impending rebellion well in advance, twenty days, by one account.

Gómez Robledo of course told Otermín. Later he appeared before the governor with the native messengers from Tesuque. "My lord," he explained, "here are the two Indians, who freely confess that the uprising is certain." To which Otermín is alleged to have replied, "Have them put in prison until Maese de campo Francisco Javier arrives." A fine way to react in a crisis.

Double Role of the Pecos

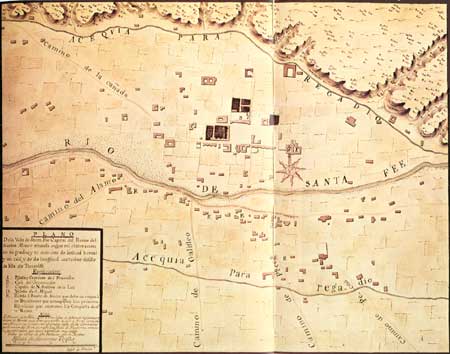

Even after the outbreak, the Pecos played a double role, or rather, they acted in the interest of at least two factions, one of which chanted, "Death to the Spaniards!," and another which evidently did not. The Pecos did not kill their minister, old Fray Fernando de Velasco. Instead, they disclosed to him the plot, and saw him off to Galisteo, where the Tanos promptly dispatched him. By most accounts, the Pecos did kill Fray Juan de la Pedrosa and at least one Spanish family. And they did join Tanos and Keres before Santa Fe on August 13 "armed and giving war whoops." The Siege of Santa Fe As news of widespread death and devastation in the outlying districts accumulated in Santa Fe, Otermín ordered the residents of the villa to come together and fortify the casas reales, that is, his thick-walled "palace" and the other government buildings on the north side of the plaza. Fray Francisco Gómez de la Cadena, guardian of the Santa Fe convento, and his assistant, Fray Francisco Farfán, consumed the Blessed Sacrament, packed up the objects of divine worship, and joined the others. When two Indians sent to scout the Galisteo Basin reappeared out of breath with word that "all the Indians of the pueblos of the Pecos, San Cristóbal, San Lázaro, San Marcos, Galisteo, and La Ciénaga, who numbered more than five hundred, were one league from this villa on the way to attack it and destroy the governor and all the Spaniards," the defenders dug in for a siege.

Leading this first wave of rebellious Pueblos was a Spanish-speaking Tano named Juan, whom Governor Otermín had sent out three days before with a letter for Alcalde mayor José Nieto at Galisteo. He rode a horse and sported a priest's sash of red taffeta. Armed like a Spaniard with arquebus, sword, dagger, and leather jacket. Juan agreed to parley with Governor Otermín in the plaza. He was not intimidated. He presented the governor with an ultimatum. Many more Indians were on their way to attack Santa Fe. They were bringing two crosses, one white and the other red. If the Spaniards chose the white cross, they would be spared to leave New Mexico. If they chose the red cross and war, they would surely die.

Otermín countered with an offer of pardon. Juan laughed and spurred his horse back across the Río de Santa Fe to the Analco district where the rebels greeted him "with bugle, with solemn pealing of the bells of the San Miguel chapel, and with hurrahs, mocking the Spaniards." When the natives began pillaging the abandoned houses of the Mexican Indians who lived in the barrio of Analco and then set fire to the chapel of San Miguel, Otermín dispatched a troop of soldiers to disperse them. But the rebels, taking cover in the gutted houses, put up such a fight that the governor was obliged to join the action himself.

The battle lasted most of the day. Just as the Spaniards put the Pecos and Tanos to rout, hundreds of newly arrived Tewas, Taos, and Picurís, threw themselves at the villa from the other side, drawing the defenders back to the casas reales. When the sun set, the Pecos and Tanos, having suffered heavy casualties, withdrew, leaving the siege of Santa Fe to the Indians of the north. After all, the revolt was their idea. The siege lasted a week. The Pueblos cut the water supply to the casas reales. They had already begun their victory celebration when a do-or-die force of mounted Spaniards suddenly broke out, caught the besiegers off guard, and trampled some of them under the hoofs of their horses. They claimed to have killed more than three hundred in all. They captured forty-seven. The rest were soon in flight. Next day, August 21, after he had interrogated and executed the prisoners and provisioned everyone for the road from his own stores, Governor Otermín led the orderly exodus of a thousand refugees out of the villa that had served as seat and symbol of Spanish authority for seventy years. By the Blessed Mother of God, he would be back. [4]

Spaniards Retreat down the Rio Grande Filing past Santo Domingo, they looked in vain for signs of life. There was evidence of a struggle in the convento. The bodies of three friars, among them ex-custos Fray Juan de Talabán, had been dragged into the church and buried in a common grave. Five more bodies lay outside. All along the valley, similar scenes of carnage greeted the forlorn column. They halted at the narrows south of San Felipe, not far from the home of swaggering Cristóbal de Anaya Almazán, who had risen to the rank of sargento mayor despite his trial by the Inquisition. His naked body and those of his wife, six children, and several other persons were heaped up at the front door. The revolt had wiped out the entire Anaya clan, save one. Sickened by the sight, Francisco de Anaya, a brother of Cristóbal wounded in the fighting at Santa Fe, thought of his own family. All of them dead. Unlike many of the refugees, don Francisco and a third wife would later return to New Mexico in the train of Diego de Vargas. In 1694, the reconqueror would name him alcalde mayor of the Pecos. [5] A Tano Relives the Outbreak Near the estancia that had been Cristóbal de Anaya's, Otermín summoned a Tano Indian known as Pedro García to appear before him. It was August 25. The day before, while a pack of rebels harried the rear of the retreating cavalcade, this Tano, "who did not want to be a rebellious traitor," tried with his wife and another woman to catch up. The rebels grabbed the two women but he eluded them and, covered by Spaniards, reached safety. Born, reared, and employed in the household of Alcalde mayor José Nieto, whose estancia lay only a league or so from Galisteo, Pedro now related to Otermín what he had seen and heard during the first days of the revolt. Like a brush fire in the wind, word of the planned uprising had spread from San Cristóbal to all the Tano pueblos, and to Father Custos Juan Bernal. Bernal had alerted Alcalde mayor Nieto and the other Spaniards, who gathered up their families and made for Galisteo. The next day, while Pedro was chopping weeds in a plot of maize on the Nieto estancia, he looked up to see Bartolomé, cantor mayor of the pueblo of Galisteo, coming toward him, his eyes filled with tears. "What are you doing here?," asked Pedro. The hysterical reply, if Pedro's memory served him, went something like this:

Governor Otermín asked Pedro if he knew why the Indians had rebelled. Pedro recalled what Bartolomé had said. The Pueblos were tired of all the work they had to do for the Spaniards and the missionaries. It rankled them that they did not have time to plant for themselves or to do the other things they needed to do. Fed up, they had rebelled. Later Pedro had learned that the rebels had put to death Custos Bernal and Fray Domingo de Vera at the pueblo of Galisteo. They had martyred Fray Manuel Tinoco of San Marcos and Fray Fernando de Velasco of Pecos within sight of the pueblo as the two missionaries hurried to join Bernal. The roll of Spaniards killed that day included Alcalde mayor Nieto, Juan de Leyva, Nicolás de Leyva, their wives, and their children. Several of the women they kept alive. They ransacked the Spaniards' homes. Meanwhile, the Pecos arrived. Joining forces, Tanos, Keres of San Marcos, and Pecos had marched off to assault the villa of Santa Fe. Defeated there, they had come back in foul humor. Because six Tanos of Galisteo had been killed and many others badly wounded, the Indians of that pueblo vented their rage on the women captives they held. Three of them, Lucía, María, and Juana had belonged to Pedro, or so he said. Another named Dorotea was the daughter of Maese de campo Pedro de Leyva. All died. Concluding his testimony, Pedro explained why he had fled to overtake the retreating Spaniards. Word had come from the Tewas, and from Taos, Picurís, and Utes, that they would annihilate any Indian, or pueblo, who refused to participate in the revolt. For that reason, and because he was a Christian, Pedro had resolved to throw his lot with the Spaniards. [6] Evacuation of Río Abajo As Otermín listened to Pedro's story near the pillaged Anaya house, two hundred and eighty miles downriver Father Francisco de Ayeta received at El Paso the first jumbled reports of the disaster. They came from the Río Abajo. Ever since about 1660, the kingdom of New Mexico had been divided for purposes of administration and defense into two major districts known as the Río Arriba and the Río Abajo, literally the upriver and the downriver sectors of the Rio Grande Valley. The governor commanded upriver, and the lieutenant governor downriver. At La Bajada, where the road from Santa Fe wound down the black basalt descent to the valley just above Santo Domingo, the traveler passed from Río Arriba to Río Abajo. The uprising of 1680 had cut all Spanish communications between the two regions. In the Río Abajo, the scared survivors, fifteen hundred of them, had flocked together at Isleta. Assuming that Otermín and everyone else upriver were dead, Lt. Gov. Alonso García and the whole crowd had started south on foot to save themselves. They had with them "a multitude of small children." At El Paso, meantime, Father Ayeta, reacting with his usual vigor, unloaded some of his supply wagons and outfitted a rescue expedition of armed men, friars, and provisions.

A Tiwa Explains the Revolt When Governor Otermín learned that the Río Abajo people were already retreating downriver, he sent riders ahead with orders for them to stop and wait for him. At Alamillo, north of Socorro, the governor interrogated another Indian, an aged Southern Tiwa man of Alameda captured on the road. What had possessed the Pueblos to forsake their obedience to God and king, Otermín demanded through an interpreter. The old man's reply was direct. "For a long time," he said,

United at Fray Cristóbal, the entire Hispanic community of New Mexico—less some 380 colonists and twenty-one Franciscans dead—resumed their inglorious trek southward through the dry Jornada del Muerto. [7] Upriver, the rebels were celebrating. Pretentions of El Popé

Just what the Pecos were doing is difficult to determine. If, as Fray Angelico Chavez suggests, a strapping mulatto named Naranjo, with big yellow eyes and a burning hatred of Spanish injustice, did assume the clever guise of the Pueblo "ancient one" Pohé-yemo and engineer the revolt from a kiva at Taos, he kept to the shadows. The conspicuous leader was El Popé, an ambitious, embittered San Juan medicine man flogged in 1675 at Governor Treviño's orders and harried from his pueblo by Francisco Javier. Once the Spaniards had gone, he took all the credit himself. [8] El Popé was a paradox. He lashed out against everything Spanish, and he did it as only a Spaniard would. The Pueblos, driven to exasperation by demands for tribute and work and by the persecution of their native religion, had joined together to cast off their oppressors. For a few days or weeks, they had coordinated their efforts. But beyond that, they had no tradition of united political action. It was the Spaniards who had imposed a common sovereignty. Thus El Popé, in his effort to hold together what had been wrought against the Spaniards, ruled in the manner of a Spaniard. He even swaggered like one. Testifying late in 1681, during Governor Otermín's bootless attempt at reconquest, several Pueblo captives described the administration of his would-be native successor.

They hacked santos, tore up vestments, and fouled chalices with human excrement. To erase their Christian names and cleanse themselves of the water and holy oils of baptism, El Popé commanded that they wash in the rivers with yucca-root soap. Anyone who harbored in his heart a sympathy for priests or Spaniards would be known by his unclean face and clothes, and he would be punished accordingly. They must not even speak the name of Jesús or Mary or the saints, under pain of whipping or death.

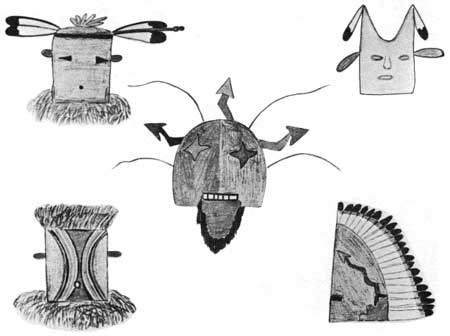

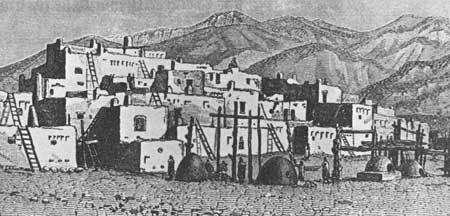

Demise of a Monumental Church In their campaign to eradicate lo español, someone demolished the massive Pecos church. The Pecos later claimed that they did not, that the Tewas had done it. And perhaps they had, during El Popé's triumphal tour. Pecos or Tewas, or both, it was no mean feat. The Spaniards said that the rebels "burned" the great monument. The roof and the heavy vigas, the choir loft, and other wooden features would have burned, but not the towering butressed adobe walls. [10] Firing the roof must have been spectacular. The rebels probably heaped piñon and juniper branches and dry brush inside the cavernous structure. When the roof caught and began burning furiously "a strong draft was created through the tunnel of the nave from the clearstory window over the chancel thereby blowing ashes out the door." It was like a giant furnace. When the fire died down, the blackened walls of the gutted monster still stood. To bring it low, Indians bent on demolition clambered all over it, like the Lilliputians over Gulliver, laboriously but jubilantly throwing down adobes, tens of thousands of them. Unsupported by the side walls, the front wall toppled forward facade down, covering the layer of ashes blown out the door. With an explosive vengeance, the Pueblos had reduced the grandest church in New Mexico to an imposing mound of earthen rubble. They did not raze the entire convento. The two-story west side suffered most. Here the Father guardian had had his second-floor cell with its mirador looking out in the direction of Santa Fe. The Pecos may have lived in some of the rooms. A circular kiva twenty feet across was dug in the corral just south of the convento and faced with adobes from the fallen church. Bedrock lying close beneath the convento must have thwarted the defiant intrusion of this "house of idolatry" right into the friars' cloistered patio. But the symbolism was clear. The ancient ones had overcome. The saints, mere pieces of rotted wood, were dead. [11] During the following year, if the Spanish accounts are accurate, the rebel faction at Pecos twice confirmed that they would defy a return of the Spaniards. Their earlier defeat at Santa Fe had not destroyed their rebellious spirit. When a couple of Indian servants who had retreated to El Paso with Spanish masters ran away and appeared again among the Pueblos, some of the Pecos who had fought at Santa Fe recognized one of them as an ally of the Spaniards. The traitor paid with his life. [12] Otermín's Abortive Reconquest Governor Otermín did attempt a reconquest in the winter of 1681, but it aborted. He and Father Ayeta badly misjudged the temper of the rebels. Moving upriver with their none-too spirited three hundred soldiers, servants, and Indians, the Spaniards half expected to be greeted as liberators by throngs of repentant pueblos. The Piro communities lay utterly deserted, so they set fire to them. They captured Isleta by surprise. The friars absolved the people, baptized their infants, and burned the objects of their idolatry. From here, Otermín sent the veteran Juan Domínguez de Mendoza with sixty picked horsemen and some Indians on foot to scout conditions upriver. As far as Cochiti, the wary Domínguez de Mendoza found that the Pueblos, defying driving snow and cold, had taken to the hills. Making his camp in the protected plaza of Cochiti, the Spaniard encountered nearby hundreds of rebels gathered on a fortified mesa. Domínguez and his men claimed to recognize among them Taos, Picurís, Tewas, Tanos, Pecos, Keres, Jémez, Ácomas, and Southern Tiwas. In a series of parleys, replete, in the Spaniards' report, with pious rhetoric, embraces, and copious tears of contrition and absolution, the rebels very nearly caught Domínguez in a trap. The mestizo Alonso Catiti, leader of the concourse, begged for peace, and for time to send messengers to all the people so that they would come down to their pueblos and receive the Spaniards. Actually he was buying time to rally his forces. Indian informers told Domínguez that Catiti planned to send into the Spaniards' camp the most comely Pueblo girls and to spring his trap while the enemy enjoyed the carnal pleasures of the bait. Recognizing their peril, the Spaniards beat an orderly retreat to the camp of Governor Otermín. Just before the entire expedition turned back for El Paso, Father Ayeta expressed his disillusionment. He had expected Pueblos by the hundreds, sorely abused by Apaches and despotic rebel leaders, to fall on their knees and beg for absolution. Instead he had found them "exceedingly well satisfied to give themselves over to blind idolatry, worshipping the devil and living according to and in the same manner as when they were heathen." It was a shock to the evangelist.

Pecos Foreign Policy If in fact some Pecos were party to Alonso Catiti's "perfidy," it is not likely that the entire pueblo cooperated to repulse the Spaniards. Traditionally aloof and internally divided, the Pecos seem to have maintained their trade and friendly relations with certain of the Plains Apaches, especially those the Spaniards called Faraones, and, whenever it suited them, to have entered into the loose and shifting Pueblo alliances. They had no use for the Tewas, an enmity noted by Spaniards for a century, ever since Castaño de Sosa. By 1689, the Pecos were reported allied with the Keres, Jémez, and Taos "in unceasing war" against Tewas, Picurís, and probably Tanos, their former allies in the attack on Santa Fe. Three years later, the Tanos and Tewas who had moved in and remodeled the casas reales in Santa Fe, swore that the Pecos and Apaches were their mortal enemies. [14]

What deference, if any, the Pecos practiced toward the various rebel leaders is not apparent. Some Pecos obviously responded to the calls of El Popé and Catiti. But after the initial fall of Popé, which had already occurred by the time Otermín reappeared in 1681, they do not seem to have acknowledged his successor, Luis Tupatú of Picurís. Curiously enough, not one of the many Pueblo rebels mentioned by name in the Spanish records of the 1680s was identified as a Pecos. In sharp contrast, the Spaniards would record by name and deed in the next decade a dozen prominent Pecos. Some would give aid and comfort to the reconquerors. Others, as the fatal rift widened, would press for another revolt.

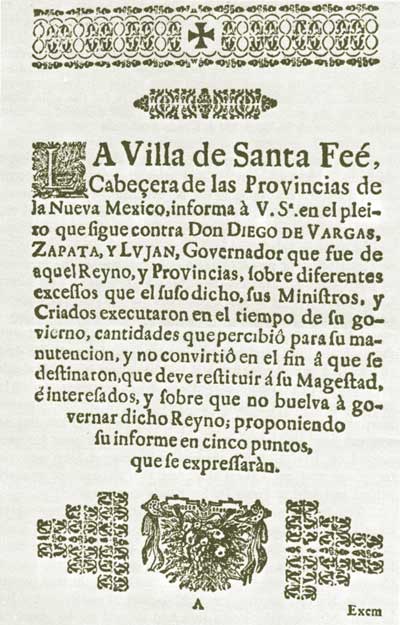

Diego de Vargas Takes Over Had they met, don Diego José de Vargas Zapata y Luján Ponce de León y Contreras, last legitimate male descendant in the noble Vargas line of Madrid, might have looked down his aquiline nose at the criollo Juan de Oñate. A strutting aristocrat hungry to perform glorious deeds in an inglorious age, Gov. Diego de Vargas, capable, cocksure, and visibly daring, on February 22, 1691, assumed command of the dispirited New Mexico colony in exile. He found El Paso a hole. The poverty, the misery, and the constant dread of Indian attack had driven many New Mexico refugee families to desert the El Paso settlements. A muster of men capable of bearing arms; counting not only the poorly equipped presidial garrison organized in 1683 but Indian allies as well, turned out scarcely three hundred in all. There were few horses and mules, an acute shortage of grain, and almost no livestock. Sumas, Mansos, and Gila Apaches daily threatened life and property. As he labored to overcome these obstacles, the new governor found himself drawn into Indian wars on the Sonora frontier to the west. Finally, in August 1692—while witches were being hanged in the Massachusetts Bay Colony—don Diego de Varges embarked on the venture that would make him a national hero. [15] When the Pecos first heard he was coming, they evacuated their pueblo. At Santa Fe, the Spanish governor had symbolically repossessed the villa, barely averting a battle by his sheer boldness and his confident preparations for a siege. Luis Picurís, formerly called Tupatú, leader of the Tewa-Tano-Picurís alliance, had come down from the north and to all appearances had made his peace with the invaders. Among the enemies of his people, Luis had identified "the nation of the Pecos, which is very numerous, and which maintains friendly relations with the Apaches they call Faraones." Now the Spaniards, accompanied by Luis and many warriors, were marching on Pecos. Vargas Marches on Pecos Having camped out of view of the pueblo, Vargas and his soldiers received absolution from Fray Miguel Muñiz de Luna early Tuesday morning, September 23, and advanced. As usual, the governor had instructed the men to cry out five times on their arrival at the pueblo the hymn "Alabado sea el Santísimo Sacramento," Praise be to the Blessed Sacrament. Not until they saw him unsheath his sword were they to shout the "Santiago!" and charge. As the mounted column moved forward through piñon and juniper, scouts picked up the fresh tracks of two Indians on horseback leading in the direction of the pueblo, as if they had alerted the Pecos. Descending a hill and a steep arroyo, they at last came in sight of the imposing earth-colored fortress. Two columns of smoke curled upward, seemingly from the pueblo. Vargas divided his horsemen. They would attack on three sides. Just then, the Indian auxiliaries passed back the word that the rebel Pecos were coming out on horseback. Vargas encouraged his men. If these Indians wanted battle, the Christians "should trample them under foot, capture them, and kill them." But be warned: they could have Apaches with them. Now the Spaniards closed at full gallop. Pecos was deserted. Believing that the two Indian riders had given the warning only a short while before, Vargas ordered his men to follow what tracks they could. Soon the Spaniards were scattered all over "the mountainous ridge that borders on the maize fields on the other bank of the river from this pueblo, the ravines, ascents, and barrancas." With his guard, the governor rode down into a deep arroyo where one of his servants discovered children's footprints. A shot rang out, echoing through the mountains in the still air. Vargas spurred his horse to where a soldier was descending with an aged Indian woman as his prisoner.

Vargas Interrogates Pecos Prisoners The governor summoned "general interpreter" Pedro Hidalgo, a swarthy, well-built man, thick of beard, with short curly hair and the scar of a burn on his neck. Born and reared in New Mexico and now in his mid-forties, Hidalgo had witnessed the death of one of the missionaries in 1680 and lived to tell about it. Whether or not he understood much of the Towa language of Pecos, as well as Tano, Tewa, and Tiwa, the willing Hidalgo interrogated the old woman for Vargas. Where had the Pecos gone, when, and for what reason, the governor wanted to know. If Hidalgo understood her correctly, her answer revealed that the Pecos were torn. The young people had cleared out six days before, as soon as they heard that Vargas was at Santa Fe. The old men of the pueblo wanted to go meet the Spanish governor and sue for peace. The young men had said no, and had prevented their elders from going. The few Pecos who stayed behind, while working that morning in their maize fields, had been warned by the two Indian riders. Another prisoner was brought to Vargas, this one a man who appeared to be about sixty, stark naked. Ordering the woman to give her compatriot one of the skins she wore to cover him up, the Spanish governor had Hidalgo ask him the same questions. He gave the same answers. Vargas decided to make him an emissary. Explaining to the old Indian through Hidalgo that he had come to pardon the Pecos in the name of the king, the Spaniard urged that he go to his people and convince them to return peacefully. No harm would come to them or their property. As a sign of peace, the governor hung a rosary around the Indian's neck. He had him make a little cross just over a quarter-vara long and attached to it a letter as a safe-conduct so that the soldiers would not kill him. Then he embraced the old man and sent him on his way, "repeating to him that he should believe me, and that I would wait at the pueblo for him and his people or for whatever answer they entrusted to him." Vargas waited four days. He and his soldiers helped themselves to lodging in the pueblo itself, which the governor found to be "very large, and its houses three stories tall, and entirely open." The place was well supplied with maize and all kinds of vegetables. Combing the rocky hills and arroyos that first day, the soldiers rounded up a total of twenty-seven prisoners. They also discovered among the trees caches of animal skins left by the fleeing Pecos, indicative perhaps that the Spaniards had just missed a party of Plains Apache traders. Between two and three that afternoon, another venerable Pecos showed up bearing the cross that had been sent earlier in the day with the first emissary. The Pecos Divided Again This second old man told Vargas the same story, that the old people and the women had not wanted to abandon their pueblo, but the young braves, "los mocetones who defend them from the enemies who do them harm and engage in war," had compelled them. He also informed the Spaniards that the earlier emissary was in fact the Pecos governor, who now was trying to round up his dispersed people. As an incentive, Vargas vowed that he and his men were ready to move out the moment the Pecos returned to their homes. He reiterated his desire that the fugitives return to the fold as vassals of the Catholic king and as good Christians, and that they reconcile their differences with The Tanos and Tewas, some of whom he had brought with him, "so that they would be like brothers and do no harm to one another."

All day Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday the calculating Vargas attempted to negotiate a return of the Pecos. Three women, brought in by the Indian allies, greeted the Spanish governor with the "Praise be to the Blessed Sacrament." Another old messenger arrived with news that the pueblo's governor had already gathered some of the people and was awaiting others. In response, Vargas sent a physically fit younger woman who told him that she was the daughter of a former Pecos governor. Twice she tried to find her people, the second time with a soldier escort part of the way, but she failed, or so she said. Summoning a lithe young Pecos male, Vargas hung a rosary around his neck and sent him. Three more Indian women, two of whom he thought must have been over a hundred years old, were hauled before Governor Vargas, along with a youth who claimed that he had been held captive since 1680. The lad said he was a son of the murdered Cristóbal de Anaya Almazán. Reuniting him with an uncle, Capt. of artillery Francisco Lucero de Godoy, Vargas charged Lucero to teach the boy the armorer's trade. Interrupting his negotiations with the Pecos, the Spanish governor sent an emissary with the standard rosary, cross, and letter to tell the Keres of Santa Ana and Zia that he would soon be coming on a mission of peace. He was losing patience with the Pecos. On Friday, September 26, about four in the afternoon, the young Pecos runner reappeared with another youth, the only person he had found. The Pecos people had dispersed: the young rebels had threatened to kill the old men who were opting for peace. Disgusted, Vargas had these two, who gave their names as Agustín Sebastián and Juan Pedro, placed with the rest of the prisoners, while he decided what to do next. A report from Domingo of Tesuque, a leader of his Tewa allies, helped him make up his mind. Scouting in the mountains earlier that day, Domingo and his men had spied three Pecos on a ridge above them. Domingo called to them to come down, that it was safe. The Pecos were wary.

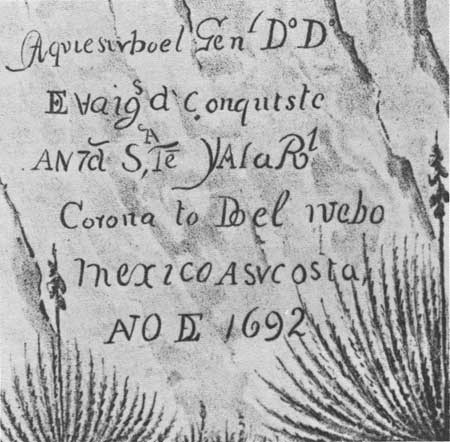

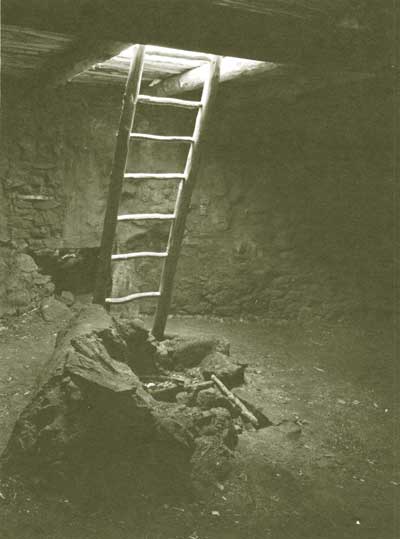

Vargas Withdraws in Peace To Vargas the message was clear. He was wasting his time. At this point, don Diego reached one of the most far-sighted decisions of his career, or, as he put it a few days later, "I acted with such judicious and prudent resolution." By their refusal to accept his offer of pardon, the Pecos had shown themselves to be, in his words, "rebellious and confirmed in their apostasy." He could punish them, burning their pueblo and their maize in the tradition of his predecessors, or he could release the twenty-eight Pecos he held, leave everything including kivas, "many of which were found in this pueblo," stores, and fields unharmed, and withdraw. He chose the latter course. Early Saturday morning, he freed the Pecos prisoners with an admonition to tell the others of their good treatment. As a symbol of peace he ordered a large cross set up in the pueblo and others painted on the walls. He left a cross half a vara long and a piece of paper marked with a cross as signs of safe-conduct for the Pecos peace delegation he hoped would come looking for him. Then, taking only the Anaya boy, three Tiwa women with their three infants, and a Spanish-speaking Jumano woman, all previous captives of the Pecos, don Diego de Vargas led his soldiers and allies out of the pueblo past the great mound that had been the church. By three that afternoon, after a strenuous twenty-mile march by "the bad road through the sierra," really only a horse trail, he was back in camp before Santa Fe. [16] By his restraint at Pecos—something the Pueblos did not expect of Spaniards—Diego de Vargas had cut the ground out from under the young hawks. The soldiers had not even ravaged their kivas. Vargas was gambling. By this act of good faith, he hoped to win an ally. The Peaceful "Reconquest" Rolls On Three weeks after he had spared Pecos, don Diego returned to collect his due. In the interim, he had triumphantly toured the Tewa pueblos, the relocated Tano pueblos of San Cristóbal and San Lázaro, and Taos, everywhere receiving the formal submission of the natives. He had been obliged to talk the Taos, erstwhile allies of the Pecos, down out of the mountains. After the usual ceremonies and the baptism of ninety-six Indians, two Taos leaders asked to see Vargas in his tent. Speaking through interpreter Hidalgo, the two explained that since they were now all brothers, the Spanish governor should know about a plot against him. Two young Taos on their way home from the Zuñi pueblos had come upon a great council allegedly attended by "all the captains of the Zuñi nation as well as the Hopi, Jémez, Keres, Pecos, Faraón Apaches, Coninas of the Cerro Colorado, and many others from other parts." Held near Ácoma, it had lasted three days and three nights. The plan was simple: join forces, ambush, and annihilate the Spaniards. Thanking the informants, Vargas called in his Tewa and Tano captains and told them to have their best men at Santa Fe by October 16. He would march first to Pecos, then to the Keres and Jémez pueblos, receiving the homage of each. If they refused, he and his allies would destroy them without quarter. Aware of the friendship between Taos and Pecos, he asked for two swift Taos youths to carry word to the Pecos. He was on his way to make peace. This time he expected their compliance. From Santa Fe, a buoyant Vargas wrote to Viceroy the Conde de Galve. Counting the villa, he had now "reconquered" thirteen towns for God and king. As for himself, it was payment enough knowing "that no one has been bold enough to under take what I, by divine grace, have achieved to date." The dispatch, incredibly enough, reached the viceroy in thirty-six days, setting off in the capital a grand celebration, pealing bells, and the festive illumination of the cathedral. Already don Diego was the toast of New Spain. [17] Reconqueror Welcomed at Pecos This time the Pecos were waiting for him. They crowded around the entrance to the pueblo, some of them holding aloft arches of evergreen branches. They had set up a cross, "large and very well made." At about two in the afternoon of October 17, 1692, a Friday, as Diego de Vargas and his party of mounted Spaniards approached, they stepped back opening a path. Those who remembered chanted the Alabado sea. The Spaniards responded gratefully. Riding straight into the pueblo with his ensign, who held high the royal standard, the erect, supremely confident Vargas dismounted in the plaza of the house block where he had stayed on his first visit. His officers, his secretary, the interpreter Pedro Hidalgo, and two Franciscan chaplains in their familiar blue habits attended the governor. Some of the several dozen soldiers may have sat their horses to control the crowd in case of trouble. This time Vargas had with him no Indian auxiliaries. Those from El Paso he had sent with the baggage train and spare horses to await him at Santo Domingo. And he had excused the Tewas and Tanos, who had not yet harvested their crops "because of the foul weather they have had." On that gray fall afternoon, the delicious smell of piñon and juniper fires hung over the teeming plaza while hundreds of Pecos, bundled against the chill in their buffalo robes and blankets, looked on from the rooftops. Vargas through interpreter Hidalgo, delivered a speech, as he had done in all the pueblos. As governor and captain general of the kingdom and provinces of New Mexico and castellan of its armed forces and garrisons by order of His Majesty, he, Diego de Vargas, had come a great distance to restore what belonged to the king, not only this land but also the people. "for he was their lord, their rightful king, and there was no other." They should consider themselves blessed to be vassals of such a king.

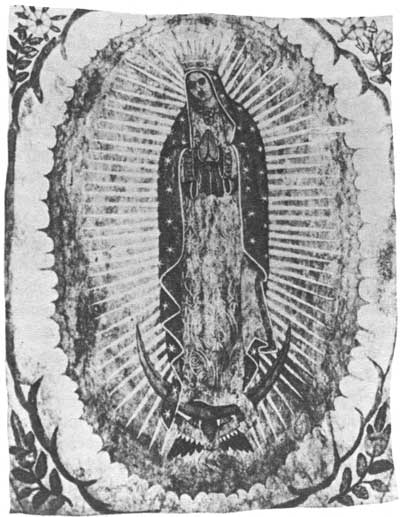

The Spanish governor called to the ensign to hoist the royal banner three times. Hung on a processional staff, it bore the image of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios, don Diego's special patroness. A squad of soldiers stood at attention with swords unsheathed. Each time the banner went up, Vargas led the crowd in the cry, "Long live the king, our lord! God save him! Charles the Second! King of the Spains, of all this new world, and of the kingdom and provinces of New Mexico, and of these subjects newly won and conquered!" Each time, the soldiers responded, "Long live the king! May he reign in happiness!" Jubilantly, amid cheering, the soldiers threw their hats into the air. Pecos, its lands, and its people had been reconquered. Falling on their knees, the friars intoned the Te Deum Laudamus. The Pecos Absolved Having rendered unto Caesar, Vargas now told the Pecos that the reverend missionary Fathers would absolve them of their grievous apostasy, and of all the other sins they had committed in the course of their revolt, and that aferward they would baptize their children born since 1680. As Christians, he admonished, they must select godparents and bring forward their unbaptized. If any of them wished, he himself, the governor and captain general, or one of his men would serve as godfather. Fray Francisco Corvera, a native of Manila, headed Vargas' three-man chaplain corps. Fray Cristóbal Alonso Barroso assisted at Pecos, while the third friar, Miguel Muñiz de Luna, ministered to the other detachment at Santo Domingo. Father Corvera delivered a homily. Pedro Hidalgo translated as best he could. The Pecos were instructed to kneel on both knees and to fold their hands. After the friar had intoned the general absolution, he and Father Barroso administered simple baptism to two hundred and forty-eight persons, mostly children from nursing babies to twelve-year-olds, as parents and godparents filed by. Don Diego stood as godfather to a son of "the captain they obey," and to many others, as did his soldiers. Compadres now, Spaniards and Pecos embraced. Two years later, the missionary assigned to Pecos would supply the ceremonies to all these simple baptisms in a temporary but proper church, anointing each individual with blessed chrism. Ironically, some of the Pecos men, whose children he baptized in 1692, would bury Father Corvera at San Ildefonso in 1696, a victim of the Tewas' second revolt. Vargas Installs Pecos Officials Saturday dawned cold and overcast. It began to snow. As a matter of policy, Vargas had camp pitched outside the pueblo so as not to displace or molest any of the inhabitants. According to the governor's journal, on this inclement morning, interpreter Hidalgo came to his tent with a request from "the old and eminent natives of this pueblo of the Pecos, in a body." They wanted him to appoint pueblo officials, the way the Spaniards did before 1680. By securing his sanction of their leadership, the elders meant to strengthen their hand over the resistance faction. Don Diego consented. Speaking again through his interpreter, Vargas told the assembled Pecos that they must elect of their own free will Indians to serve as their pueblo governor, lieutenant governor, alcalde, and alguacil, as well as two fiscales and two war captains. When they had done this, he administered the oath, exhorting them "in the utmost detail through said interpreter to respect and fulfill the duties of their offices to the greater service of Both Majesties." Father Corvera then gave the oath to the two fiscales, whose duties as assistants to the missionaries did not at this time amount to much in the absence of resident priest and church.

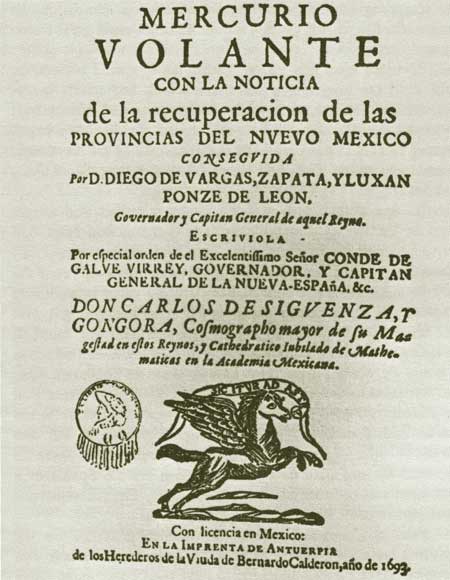

When the snow and rain stopped, about two in the afternoon, Vargas gave the order to decamp "despite the bad weather." By three the column had formed up. "Having taken my leave of these natives," his journal reads, "and having reiterated to them that they should pray and live as Christians, which they promised me they would do, I set out." Curiously, don Diego failed to record in his journal, now or on his earlier visit, the state of the Pecos church. A great heap of melted adobe, beyond repair, it was evidently not worth the mention. No matter. Vargas was satisfied. Pecos, whose population he estimated "from its house blocks and plazas" at about fifteen hundred, was his, number fourteen on his tally of reconquest. [18] Taking "the wagon road," they camped that night at abandoned Galisteo, and next day passed through San Marcos, where Vargas noted that "some of the rooms and walls of its house blocks and dwellings survive, and likewise the walls and nave of the church as well as those of the convento are in good condition." Reunited with the rest of his force at Santo Domingo, the tireless reconqueror mapped his route through the Keres and Jémez pueblos, then westward to Ácoma, Zuñi, and as far as Awátovi, Walpi, Mishongnovi, and Shongopovi among the defiant Hopi. Everywhere, demonstrating an almost suicidal boldness, don Diego de Vargas won the day. The "Bloodless" Reconquest Complete Before Christmas, they were back in El Paso. The final tally, as reported by Vargas to the viceroy, stood at twenty-three pueblos rewon, seventy-four Indian and Spanish captives rescued, and 2,214 Indians baptized. Or, in the words of a news bulletin describing the heroic feat, "An entire realm was restored to the Majesty of our lord and king, Charles II, with out wasting a single ounce of powder, unsheathing a sword, or (what is most worthy of emphasis and appreciation) without costing the Royal Treasury a single maravedí." To make good on this "bloodless reconquest," Vargas had yet to recolonize New Mexico. In the months ahead, he devoted himself zealously to recruiting, fund raising, supply, and to seeking preferment worthy of his deeds. In a long letter to the king, written from Zacatecas in May 1693, don Diego beseeched his sovereign to grant him the title of Marqués de los Caramancheles, two estates near Madrid, "with lordship over them." To continue in the royal service, he also bid for the governorship of Guatemala, or if that be taken, the governorship of the Philippines, or if that be taken, the governorship of Chile, or if that be taken the governorship of Buenos Aires and the Río de la Plata. [19] "El hombre propone," says the Spanish maxim, "y Dios dispone." Man proposes and God disposes. It was the Other Majesty's will that Diego de Vargas die in New Mexico. Vargas Plans Recolonization The second phase of don Diego's task entailed more work and less glory, and it was by no means bloodless. He welcomed the viceroy's praise and his approval of a government-subsidized, one hundred-man presidial garrison for Santa Fe. Besides those already in the El Paso area, he reckoned he needed as many as forty more priests, plus Custos Salvador de San Antonio, a New Mexico veteran. The twelve thousand pesos offered initially by the viceroy, Vargas considered insufficient to outfit, transport, and maintain for six months the five hundred families of colonists he intended to take. He had decided already where they should settle: 150 families at Santa Fe; 100 in the vicinity of Taos; 50 near Santa Ana; 100 at Jémez; 100 along the Rio Grande from Angostura, south of San Felipe, to Sandía; and 50 at Pecos, bringing the total, incidentally, to 550. Diego de Vargas' reason for projecting a civil settlement in the vicinity of Pecos—a proposal not realized in fact for another hundred years—was defense.

They came together at unprosperous El Paso, where for a couple of weeks mission and presidio were inundated by a swarming camp that tripled the population—a hundred soldiers for Santa Fe, some with families, seventy assorted families of colonists, widows and singles and servants, eighteen Franciscans, and an unlisted number of Indian allies, probably twelve hundred persons in all, plus wagons and gear and a thousand mules, two thousand horses, and nine hundred milling head of cattle, sheep, and other sundry stock. More or less formed up, the straggling, motley train began to move out slowly on the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, October 4, 1693, amid great festivity and cursing. The journey north was a nightmare. The wind blew bitter cold, food ran low, wagon wheels came off, and nearly every one was sick. Worse, as Vargas and his vanguard of fifty men scouted ahead through the first abandoned pueblos, they began hearing rumors that most of the Indians, fortified on mesa tops, intended to resist. Only the Keres of San Felipe, Santa Ana, and possibly Zia favored the Spaniards' return. [21] Juan de Ye Offers Services At San Felipe, unexpectedly, a Pecos hailed don Diego. Juan de Ye, whom Vargas always addressed as don Juan, had arrived to pay his respects. This was "the captain they obey" whom Vargas had inaugurated as pueblo governor at Pecos the year before, and whose son, like those of so many other native leaders, was his godchild. Apparently, Juan had brought with him his lieutenant governor, alcalde, alguacil, and war captains. Learning of the Spaniards' presence from a Pecos lad who was in Santa Fe when Vargas' two Tano emissaries appeared, Juan had hastened to San Felipe to assure the Spanish governor that the Pecos welcomed his return. He had made that clear to the Tewas and Tanos, and he had come in person to tell don Diego. Whether Vargas sensed it at this stage or not, Juan de Ye, until his probable death on a mission for the Spaniards a year later, was to prove almost indispensable. The reconqueror's refusal to destroy Pecos in 1692 had paid off. Juan de Ye now briefed the Spanish governor on the fight that lay ahead. As far back as the summer, the rebels who occupied Santa Fe had told Juan to have the Pecos "make many arrows so that all of them together" could attack the Spaniards when they came. A council had been held in the Tewa pueblo of San Juan, at which, according to the Pecos governor, the half-breed Pedro de Tapia had planted a cancerous seed of discontent. An interpreter with the Spanish expedition of 1692 who had since died, Tapia told the Pueblos that Diego de Vargas was a monster. Even though he pardoned them in 1692, his ultimate goal was to slaughter them all, sparing only the children born since 1680. This seed, nurtured in the fertile soil of their guilt, had grown into an effort to unite all the Pueblos against the Spaniards. "If it is true," wrote Vargas about Tapia, "may God forgive him!" [22] A few days later, cold and complaining, the colonists, along with soldiers, friars, baggage, and animals, caught up. The entire expedition camped on the site of Cristóbal de Anaya's ruined estancia. While Vargas parleyed with a variety of Pueblo delegations and sent out supply details in all directions to trade meat for maize, camp was moved nearer and nearer to Santa Fe. The weather turned colder still, and some of the colonists whispered of deserting. Juan de Ye stayed with the Spaniards. In fact, four Pecos, mounted and armed, Felipe, Juan, Pedro, and Diego, curious to know what was keeping their governor, showed up in camp one day. Vargas welcomed them and told interpreter Juan Ruiz de Cáceres to make them understand "that I loved them all very much, that they were my children, and that their governor and my compadre, don Juan, knew this well. When they recognized this they were satisfied." A Plot to Annihilate the Spaniards Late the night of November 25, two of Vargas' captains woke him to report that don Juan and the four recently arrived Pecos had urgent news. Shown into the Spanish governor's tent and seated on the ground near his bed, the natives told of a plot to annihilate the entire expedition. This time Francisco Lucero de Godoy interpreted. As usual, Juan put the blame on Tewas and Tanos, along with Picurís and Taos. He identified their leaders, some of whom were feigning friendship. The rebels had called an all-Pueblo junta at La Cienaguilla, seven leagues from Santa Fe. Dividing their forces, they meant to attack the Spanish train simultaneously from front and rear, drive off the animals, and massacre everyone. Should the Spaniards reach Santa Fe, where the native occupants had dug a well inside and laid up provisions to withstand a siege, the plan was to stampede the invaders' horses at night, then fall on the camp. A Spaniard afoot, they were convinced, was no match. But for the refusal of the Pecos and the Jémez to join them, the rebels might already have sprung their trap. As a Christian, Vargas replied, he would proceed as if he knew nothing of the plot. He intended to give everyone an opportunity to submit peacefully. If the Tanos and Tewas chose war, he would rely, as before, on Nuestra Señora de los Remedios and her Son. He had come not to do harm but rather to encourage all the Pueblos to live in peace as Christians. He thanked the Pecos for their offer to fight at his side and to steal the rebels' riding horses and mules from the canyon where they had left them, but he prayed it would not come to that. Before dismissing them, Vargas reiterated the affection and esteem he felt for the Pecos, "because they were loyal to the king our lord, Christians, and friends of the Spaniards." A few days later don Juan was back. He and another Pecos named Juan "of his closest following" said they wanted to see the Spanish governor. Admitted to Vargas' tent about eight in the evening with interpreter Ruiz de Cáceres, they described again the threat posed by the rebel alliance, repeating their offer to capture the enemy's horses. The Pueblo occupants were preparing to defend Santa Fe, where growing numbers of rebels were gathering, and the weather was getting worse. Why then, the Pecos wanted to know, did the Spaniards not attack? Again Vargas put them off. [23] Misery in the Spanish Camp While he played the diplomatic game, a war of nerves, the Spanish camp was starving. The scant provisions acquired in trade with the Pueblos were not enough. Dissuaded by his officers from going to Pecos in person, the Spanish governor now called in don Juan de Ye. If the Pecos really wanted to aid the Spaniards, they would bring food. "I told him," said Vargas, "that he would demonstrate the strength of the good will he felt toward me as a compadre and my relative" if he went to his pueblo and traded for all the flour, maize, pinole, and beans he could get. Don Diego was thinking in terms of seventy or eighty cargas, or mule packs, of two fanegas each. Sgt. Juan Ruiz de Cáceres would accompany the Pecos, taking six slaughtered beeves and other trade goods, mules and muleteers, and an escort of twelve soldiers under Capt. Juan Holguín. The side expedition to Pecos set out about ten in the morning on December 5. It was back by December 9. The haul: an unfulfilling eight fanegas of maize, more or less, and two of maize flour. The Pecos, reported Juan de Ye, were glad to know that the Spanish governor had returned. Don Diego was welcome at their pueblo, where they would load up his mules with provisions, doubtless for an appropriate consideration in trade goods. Don Diego had to explain to the Indian that the Spaniards and their wagons were not proceeding first to Pecos but to Santa Fe instead. Once they had secured the villa, he would go down to Pecos himself to install a missionary. As a sop he presented don Juan with a horse. The Pecos, plainly, were not going hungry that Spaniards might eat. [24]

Vargas and Colonists in the Snow When finally they stood in the snow before Santa Fe, the shivering, half-starved colonists were denied shelter within. The Tanos and Tewas made no move to vacate. On December 16, they received Governor Vargas, a procession of soldiers and Franciscans, a cross, and the Te Deum inside the walls, but they did so with a foreboding reserve. Still, with his tent set up outside in the cold "a mortar shot from the plaza," Vargas decided to distribute the missionaries. If the reconqueror appeared calm in the face of the dangers and discomforts of the moment, the friars were perturbed. Everyone in camp knew of "the evil design and perfidy" of the Tanos and Tewas. Again don Juan de Ye came to Vargas' tent. This time he had definite information, relayed from a Zuñi to a Cochiti to him. Tewas, Tanos, and Picurís had congregated on the mesa of San Juan with a horde of Apaches. Dressed and armed like Spanish frontier cavalry, with leather doublets, lances, and shields, they would strike Governor Vargas when he least expected it. Meanwhile, they had arranged to steal the Spaniards' horses a few at a time. Don Juan offered to call his Pecos warriors. And again he volunteered to steal the rebels' horses. Missionaries Balk and Sign Petition Not on their lives were the missionaries going out into the pueblos. Martyrdom was a blessing, suicide was not. In addition to Santa Fe, Vargas wished to thrust ministers into Tesuque, Nambé, San Ildefonso, San Juan, San Lázaro, Picurís, Taos, Jémez, Zia, Cochití, and Pecos. What was he thinking? Had he forgotten his promise to protect the ministers of the gospel as well as the other innocent vassals of the king "who had come with such willingness to settle this land?" How could he ignore the repeated warnings of don Juan de Ye, an Indian who had proven himself "always faithful and honest in all his actions and conduct and who has not left our company in more than a month." All eighteen friars signed the petition. That same day, December 18, Fray Diego de Zeinos, secretary of the custody, delivered it to the governor's tent. Whether or not they had their facts straight, they meant to impress upon Vargas the loyalty and the credibility of Juan de Ye.

Even had he wished to overrule the friars' protest, Vargas reconsidered. This was no time to send out the missionaries. [25] The impasse continued. Tension built. An icy wind swirled the snow into drifts. Secure in their walled fortress-pueblo, the native occupants of Santa Fe mocked the Spaniards outside. Vargas doggedly kept up negotiations, all the while struggling to bring in enough food to feed his wretched colony, a few fanegas from this pueblo, five from that. From Pecos, where Sergeant Ruiz de Cáceres and his detachment received another warm welcome, came ten cargas, or twenty fanegas, of flour and ears of maize, as well as regards to don Diego. The long-exiled municipal council of Santa Fe was demanding that Vargas put them in possession of the casas reales. Children were sick and dying. At an open meeting, the leaders of the colony voiced their unanimous resolve: the rebels must go. Inside the walls meanwhile, the natives worked themselves up for a fight. The Bloody Battle for Santa Fe In the brittle pre-dawn cold of December 28, the dark figure of a messenger flitted through camp and disappeared into Vargas' tent. The rebels were about to attack. Ordering trumpet and war drum sounded, the Spanish governor called for don Juan de Ye. Now was the time for the Pecos to prove themselves. "I ordered him to send at once to his pueblo on two swift horses I gave him and alert the young warriors to come well prepared and armed." That day both sides girded for battle. Vargas appealed to the rebels to evacuate the villa peacefully. He might as well have asked each of them for his left foot.

Four Pecos appeared next morning. They reported to Juan de Ye something about their people gathering firewood for the night and staying in the foothills until a Spaniard came for them. Vargas told Francisco Lucero de Godoy to get them. In no time he was back with one hundred and forty Pecos indios de guerra give or take a few. "I received and welcomed them all," said Vargas,

Addressing his entire "army," as men and horses stood there benumbed, their breath escaping in white puffs, don Diego de Vargas reassured them that God and the Blessed Virgin were with them, a fact Fray Diego de Zeinos confirmed. Then all knelt in the snow, recited the general confession, and were absolved by the friar. Mounted up, they moved forward, and, met by a hail of shouting, arrows, and rocks, they yelled the Santiago and charged. This time the Pecos had chosen the winning side. Thirteen years before, they and their Tano allies had fought the beleaguered Spaniards of Santa Fe and lost. Now on the same ground Spaniards and Pecos retook the villa from the Tanos in a hard-fought two-day battle. Eighty-one rebels died: nine in battle, two by their own hand, and seventy executed. The four hundred who surrendered were allotted among the Spaniards for ten years' servitude. Finally the reconquerors had more than the ritual submission of the Pueblos and the boasts of Diego de Vargas. They had their capital. [26] Vargas Confirms His Alliance with the Pecos If anything, the Spanish victory at Santa Fe strengthened the alliance between Vargas and don Juan de Ye. Five days later, on January 4, 1694, when the Indian reported a threat to his pueblo, the Spanish governor responded in good faith. Ye, escorted by interpreter Francisco Lucero de Godoy, had come to Vargas' quarters at seven in the morning. An Apache sent by Ye to Pecos had returned in the night with a warning that he had spotted a large force of rebel Tewas, Tanos, Picurís, and Apaches in the mountains behind Santa Fe. They could have been moving on Pecos to avenge their loss of the villa. Vargas expressed his concern. But he was reluctant to leave Santa Fe just yet. He would dispatch don Roque de Madrid, his second-in-command. If, upon investigation, the situation required his presence, don Diego would gladly march to the defense of Pecos. Madrid took thirty men, saying that he would call for more if needed. Vargas had provided, as usual, that any horses and cueras, the valuable protective leather coats, captured from the enemy be distributed among the members of the expedition. Fray Juan de Alpuente, who rode along as chaplain, would get his first look at Pecos, where two years later he would serve reluctantly as missionary. By four in the afternoon the next day, the column was back. There had been no sign of the rebels. The Pecos to a man, Madrid reported, "were grateful for the sending of these soldiers to protect them. They welcomed them warmly, and, having the Spaniards so firmly on their side, they feel secure." [27] When Vargas marched out of Santa Fe in February to do battle with the Pueblo rebels dug in on Black Mesa, an "army" of Pecos marched with him. What don Juan de Ye and his following hoped to gain by this close association with the reconquerors, besides the protection of Spanish arms and vengeance on Tewas and Tanos, became increasingly evident that spring. They hoped to restore the traditional role of their pueblo as gateway between the Rio Grande Valley and the plains. The Spaniards had horses and goods, and once they put down rebel resistance, they would impose peace. All this was good for trade.

Juan de Ye and Plains Apaches At least twice, once in March and again in May, don Juan de Ye showed up at the governor's palace with Plains Apaches in tow. The first time there were three of them. They explained to Vargas through an interpreter that they had arrived at Pecos with three tipis of their people. There they had learned of the Spaniards' return. Willingly they had come to render homage to the Spanish governor, to make his acquaintance, and to ask his permission to bring the rest of their rancheria to Pecos to trade "about the end of the rains, which is around October." They told Vargas how they used to come and go trading in peace before the Spaniards had vanished in 1680. This trade had proven beneficial to all concerned. Just so the people they had left at Pecos would know for sure that the Spaniards were back, the three Apaches requested that half a dozen of the reconquerors accompany them that far. Vargas was delighted. He feted the three and assured them that they and their people would be welcome any time. On his orders, Maese de campo Lorenzo de Madrid, Aide-de-camp Antonio Valverde, an interpreter, and a party of soldiers and settlers rode with them over the mountain. The Pecos staged the kind of festive reception the Spaniards were coming to expect from them. The visiting Apaches

But they did not wait until October. On May 2, Juan de Ye presented himself at the casas reales in Santa Fe with a captain of the Apache rancherias of the plains and eight other Indians. Domingo de Herrera interpreted. This Apache had come in response to Vargas' previous invitation. He wanted to confirm the desire of his people to resume trade with the Spaniards when the ears were on the maize, just as in the old days. As tokens of their good faith, he laid before the Spanish governor three buffalo robes and "a campaign tent of light buffalo or elk skins." Vargas asked how far it was to their rancherias. Fourteen days, answered the Apache, and ten to where the buffalo bulls and cows roamed. There was much water, he added. Next Vargas asked "the captain of the Apaches Faraones" why he was not a Christian. Using his hands, the Indian made signs that they should pour water on his head right then. If the Spaniards would just finish off the rebels, his Apaches would come live in their pueblos and become Christians. That, Vargas allowed, was an excellent thought provided the rebels did not reoccupy them. He explained to the Indian that as an adult he would have to be instructed before baptism. He must learn the prayers which Christians said on their knees. "He trusted me and the Spaniards implicitly," Vargas wrote, "showing by the outward joy of his countenance that he was already a Christian like us." [29] Two days later at a formal audience, Ye and the first Plains Apache captain, who must have been serving with the Pecos auxiliaries, told Governor Vargas and his staff that the time had come for them and their horses to rest. It was the time for planting milpas, the time for each of them to return to his land. Before they departed, Vargas had some questions for the Apache. While the answers he gave do not rank him with the Turk, the glib plainsman did tell the Spaniards what they wanted to hear. A Plains Apache Briefs Vargas As they were having their chocolate, Vargas pointed to a silver dish and asked the Apache if they had anything like that in his land. The native said yes. Within a day's travel, there was a little range of mountains and at its base were some rocks of the same material just over half a vara tall. They called them hierro blanco, white iron. So heavy and hard were they that he had no way of breaking off a piece to bring to don Diego. After more questions, the Spanish governor told the Apache that he would pay him anything he wanted for a piece of the rock, "because it is a remedy for eye and heart disease." The Indian asked for an iron ax to break off a piece. "At once," wrote Vargas, "I ordered that it be brought as well as many goods with which I regaled him and likewise a horse he had asked me for, all of which was most pleasing to him."

The governor had also inquired about Texas and Quivira. The kingdom of the Tejas, according to the obliging Apache, lay seven days from his rancheria. Asked if there were watering places, he replied that there were rivers in abundance, many buffalo, and much fruit in the summer. Were there Spaniards? In years past there had been, but he did not know if they were still there. This answer satisfied Vargas that the Apache captain was telling the truth, for there had indeed been Spaniards in Texas recently searching for LaSalle. How far was Quivira? Using his fingers, the Indian calculated that the first settlement was some twenty-five to thirty days from his rancheria. His people knew this well because they went to Quivira to make war and capture children to trade for horses. Vargas reminded the Apache not to forget the white iron. He should bring it when the ears were on the maize, to the pueblo of the Pecos where he and his people were welcome to come and trade with the Spaniards. Vargas would give the citizens of Santa Fe permission to go down to Pecos. He would aid the Apaches in every way, and he would pay well for the hierro blanco. [30] Spaniards Join Again in Pecos Trade Fair Evidently the white iron did not pan out. When a Plains Apache captain known to the Spaniards, possibly the same one, sent word through the Pecos late in August that eleven tipis were coming to trade, Vargas made no mention of the metal. Still, he cooperated in every way. At the request of the Pecos war captains, who did not wish to offend the Apaches or miss out themselves, he postponed his campaign against the northern Pueblo rebels and decreed a trading holiday. Vargas' proclamation of the trading at Pecos was promulgated before large crowds in both of Santa Fe's plazas "to the sound of drum and bugle and in the voice of Sebastián Rodriguez, black drummer." The governor, anxious that his relatively small military force not be weakened further, imposed one restriction. Anyone who wanted to do so could go down to Pecos and enter freely in the trade, except using horses that bore his brand or were otherwise specified "on my account" as needed for war, regardless of who had them now. He who traded such a horse would lose not only the price but the animal as well. The governor had reason to be pleased. The Pecos fair was visible proof that the kingdom could live in peace, as it had before 1680. [31] Juan de Ye's Ultimate Sacrifice During the first six months of his rigorous campaign to restore effective Spanish sovereignty over New Mexico, no Indian, with the possible exception of Bartolomé de Ojeda of Zia, served Diego de Vargas as devotedly or as productively as don Juan de Ye. Whatever his motives, he was always in Santa Fe, or in the field with his Pecos auxiliaries. He entered into Vargas' negotiation to win over the rebels, on several occasions interceding to save the life of an Indian who might favorably influence his fellows. Once, don Juan came in to ask the Spanish governor's forgiveness for allowing a venerable former governor of the Jémez to live at Pecos. The old man, who still enjoyed considerable respect among his people, according to Ye, could be used to counter the propaganda of the rebellious Tewas and bring the Jémez back down from the mesas. Vargas was willing. But it would take more than diplomacy. When next the Spaniards tried force, don Juan was there with his Pecos. This time it would cost him his life. [32] On San Juan's Day eve, June 23, 1694, a disgruntled train of colonists entered the gates of Santa Fe to the sparse cheering of the citizenry. This second wave, recruited in Mexico City and shepherded all the way by Franciscan procurador fray Francisco Farfán, increased the population by over two hundred, including three French survivors of the massacred LaSalle colony. No one felt more the need for numbers than Vargas did, but at the same time, with the maize supply so desperately low, he now had to provide for just that many more bellies. His first priority was to deal swiftly with the rebel Santo Domingos and Jémez, whose harrying raids on the loyal Keres of San Felipe, Santa Ana, and Zia had caused these Indians to doubt the Spaniards' guarantee of protection. As Vargas plotted his move, don Juan de Ye rode in to say that the Rio Grande was up. Even with rafts, the crossing would be risky. Forced to shift priorities, Vargas now rerouted the expedition northward. From the stores of the abandoned rebel pueblos, by purchase, or by force, he would lay in enough maize to see his hungry colony through to harvest time. His journal entry for July 3 told of a noble but foolhardy act on the part of don Juan de Ye. They had found Taos deserted. Fresh tracks led to the peoples' accustomed refuge, a deep and rugged mountain canyon whose entrance gaped open half a league from the pueblo. A rancheria of Plains Apaches who had come to Taos to trade greeted the Spaniards with handshakes and abrazos. These were mild compared to the demonstrative welcome they gave Juan de Ye, "their friend and acquaintance." Parleying with Defiant Taos The Apaches arranged a meeting at the mouth of the canyon between Vargas and Francisco Pacheco, governor of the Taos, who suddenly appeared with a menacing number of his men. Ye considered Pacheco an old friend. He interpreted, evidently from Tiwa to Towa, with Sgt. Juan Ruiz de Cáceres or another Towa-Spanish speaker taking it from there. "With great force of words" Ye tried to persuade Pacheco and his people to come down to the pueblo and accept pardon from Governor Vargas. They had done so without harm in October of 1692, why not now? But it was no use.

"Moved by impulse and by fervent Catholic zeal," Diego de Vargas now risked his life, which he recorded in his journal, advancing to where Pacheco stood. The sun had set. Recognizing that he could accomplish little before nightfall, he bid the Taos governor an affectionate good-bye and told him that he would be waiting for him the next day at the pueblo. He had ordered camp made far enough away so that the Spaniards' horses and mules would not damage the Taos' crops. Juan de Ye repeated what Vargas had said. The wily Pacheco, feigning affection and professing the friendship of Taos and Pecos, invited don Juan to stay the night with him so they could discuss at leisure the Spaniards' proposal. Ye accepted.

Sergeant Ruiz suggested to Vargas that he order Ye to return the arquebus he was carrying, which belonged to the governor, and his mule as well. Rather than betray a lack of confidence, Vargas rode over to don Juan, who was already dismounted. He repeated the warning of Ruiz and Anaya. The Indian's reply was the same.

When neither Pacheco nor Ye showed next morning, Vargas rode to the mouth of the canyon. He told his interpreter to shout up to the Taos sentinels that if their governor and don Juan did not appear by one o'clock, the Spaniards would sack the pueblo. No one appeared and Vargas gave the order. Once broken into, the pueblo yielded a wealth of maize. For more than two days they husked and loaded the edible booty, then under cover of darkness headed north into present Colorado to double back by the easier more westerly trail of the Ute traders. As for Juan de Ye, don Diego never saw him again. From two Taos Indians captured July 7 he learned that don Juan was still alive but tied up. Ten days later, safely back in Santa Fe with the maize, Vargas heard that Ye was still missing. Several Pecos Indians "loaded with glazed earthenware to sell" had come to town. A little while later don Lorenzo de Ye, son of don Juan, arrived. His father had not returned to the pueblo. When he had listened to the Spaniard's explanation of how don Juan had gone alone and of his own free will to parley with the Taos, when he had been given his father's weapons and cloak, don Lorenzo was, in Vargas' words, "satisfied but sad about the end that had befallen his father." Through an interpreter, Diego de Vargas tried "with efficacious words" to express his sympathy. No Spaniard deserved the title reconqueror more than don Juan de Ye, governor of the Pecos. Vargas would never forget him. [33]

Refounding the Missions For the friars, the reconquest so far had been frustrating. Eager to restore their missions but unwilling to risk their lives foolishly, they had been confined to Santa Fe where they had ministered to the complaining colonists and got in one another's way. Some had served with Vargas on campaign, absolving the men before battle and the prisoners before they were shot. Originally there had been eighteen. On Palm Sunday, April 4, Custos Salvador de San Antonio, who had been openly critical of the governor, and three of the others had departed for El Paso with the wagons and mules sent to the aid of Farfán's colonists. Fray Juan Muñoz de Castro was left in charge at Santa Fe as vice-custos. Late the same month, Vargas began to talk again of refounding missions. Fresh from a victory of sorts over the rebels on the mesa of Cochiti, the reconqueror sent a delegation to the quarters of Vice-custos Muñoz. He would donate to the reestablishment of missions two hundred head of the sheep he had captured. It seemed to him only right, "because of the friendship and the good relations we have with their natives," that the first be founded for the Pecos and the second for the Keres of San Felipe, Santa Ana, and Zia. Until that time he would put the flock in the care of a trustworthy Keres. Another hundred sheep he gave to Muñoz and the thirteen religious in Santa Fe "so that they are assured of meat to eat for a few weeks." He also deferred to the friars first choice of the boys among the Cochiti prisoners. For all this Father Muñoz expressed to don Diego the friars' gratitude. [34]

Still, for five long months no mission was refounded. Not until September when Vargas, aided by Pecos, Keres, and Jémez auxiliaries, finally humbled the rebels on Black Mesa and received the allegiance of the Tewa and Tano pueblos, did the time seem right. Then, with "not only moral but physical" assurance of the rebels' genuine submission, the eight missionaries remaining in Santa Fe petitioned Vice-custos Muñoz to send them into the field. It was no coincidence that the first mission they revived was Pecos, pueblo of the deceased don Juan de Ye. [35] Father Zeinos Installed at Pecos An earnest priest if ever there was, Fray Diego de Zeinos had served as secretary and notary of the friars since their departure from El Paso. He also bore the title lector, which meant that he had been a lecturer in a seminary or university. Whatever his other credentials, Fray Diego was assigned to Pecos. [36] Governor Vargas set out for Pecos with his usual pomp on Friday morning, September 24, 1694. His purpose was two-fold, to carry out the visitation required by his office and to install Father Zeinos. With him went the royal standard, his staff, the presidial garrison, Vice-custos Muñoz, Zeinos, and the three other friars assigned to San Felipe, Santa Ana, and Jémez. Making good time over the mountain, they entered the pueblo of the Pecos early the same afternoon in time for the customary formalities. The assembled natives had heard it all before. They had anticipated this day. "They promised," according to Vargas' journal,

Vargas thanked the old Pecos governor and his natives for "their superior effort." He told them that "in order to live civilly" they must elect and present to him their pueblo officials. He made no secret of his support for the incumbent governor. "Indeed, when they understood my will, they asked me that it be thus, saying that it was their will." At two in the afternoon, the Pecos put forward their slate, returning to the Spanish governor the symbolic staffs of office so that he might present them anew and administer "in His Majesty's name the oath they must swear in legal form by God Our Lord and the sign of the Holy Cross." Sworn in were: Diego Marcos, governor

Anaya Named Alcalde Mayor According to Vargas, the Pecos then asked him to appoint Sargento mayor Francisco de Anaya Almazán, "a most worthy person," as alcalde mayor and military chief of their pueblo. Before the revolt of 1680, the alcalde mayor of the Tanos had administered Pecos as well. Anaya, in fact, had held the office for a time in the mid-1660s. Now, with the Tanos dispersed and the Galisteo Basin deserted, the governor named an alcalde mayor for Pecos alone, giving him the oath, the writ of title, and the staff of office. Described in 1681 as a man of "medium build, protruding eyes, a thick and partly gray beard, and wavy chestnut hair," the veteran don Francisco de Anaya must have been in 1694 at least sixty-one. He had outlived two wives and was wed to a third, Felipa Cedillo Rico de Rojas. With María de Madrid, who must have been a relative if not his fourth wife, he alternated as godparent for dozens of Pecos children in the next nineteen months. Vargas called him "a linguist and old soldier." By all accounts, don Francisco, unlike his pre-revolt predecessors, cooperated with the missionary in every way. Before Governor Vargas led his retinue back to the Rio Grande to perform similar rites at San Felipe, he "asked them the name of the patron saint of this chapel which is to be transferred to the church they will rebuild and erect anew in the coming year." They told him that they wished to retain the patroness who had been theirs before the deluge of 1680, Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de la Porciúncula. With that, Vargas concluded the visitation. The mission at Pecos, after a lapse of fourteen years, was reborn. [37] Zeinos as Pastor and Advocate of the Pecos The ministry of Fray Diego de Zeinos was a success while it lasted, about one year. In less than three weeks, he could boast a temporary church. Constructed by the Pecos, presumably under the supervision of the friar and Alcalde mayor Anaya, it utilized the massive, still-standing north wall of the convento. It lay atop the leveled mound covering the south wall of the pre-1680 church and measured inside roughly twenty by sixty or seventy feet. The nave paralleled that of its monumental predecessor but the orientation was reversed: the altar was at the east end, the entrance at the west. [38]

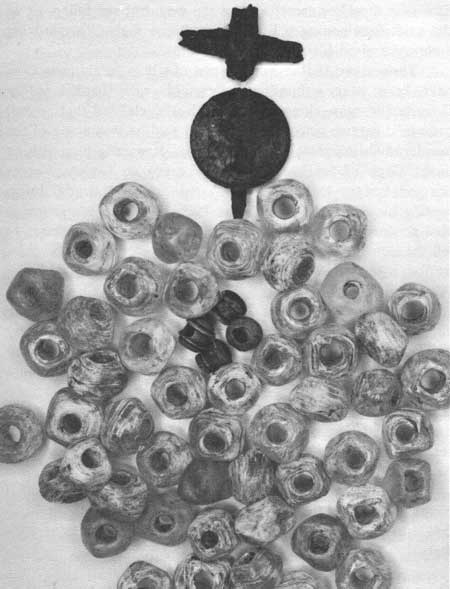

Between October 11, 1694, and September 7, 1695, Father Zeinos baptized 103 Indians, mostly infants and children. Francisco de Anaya stood as godparent for seventeen of them, María de Madrid for twelve. The new resident missionary also celebrated full solemn baptism with all the prayers and ceremonies for 240 of the 248 persons baptized in the simple form by Father Corvera in 1692, running through as many as twenty-two in one day. So that a complete record might be kept in the Pecos book of baptisms, Zeinos had each of these 240 appear with a godparent, not necessarily the same one as in 1692. Anaya thus became godfather to three children of the deceased don Juan de Ye, and to twenty-three others, while María de Madrid collected forty-three more god children. [39] To ingratiate himself with his new charges, Father Zeinos appeared in Santa Fe with a petition. Because the Pecos had demonstrated their loyalty by warning the Spaniards in 1680 and again during the reconquest, he thought they deserved a reward, "some exemption or privilege." He requested Vargas to confirm the Pecos' loyalty and forward the petition to the viceroy. The governor did so the same day. In Mexico City the viceroy's attorney pointed out that the Pueblos of New Mexico were already exempt from tribute and labor, the usual reward in such cases. That left Governor Vargas free to express to the Pecos his profound thanks in the name of the king, no more no less. [40] Custos Vargas Asks Questions On the first day of November 1694, a new custos arrived in Santa Fe. He was Fray Francisco de Vargas, a Spaniard himself but unrelated and unattracted to the lofty don Diego de Vargas. The two had already clashed, when Fray Francisco had been custos before, over mission property in the El Paso district. Now the friar had something else on his mind.