Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

A Veteran Remembers Juan Troyano, veteran of Coronado's army, had not forgotten. More than a quarter-century had passed, yet he could still see the crowded plaza of Cicuye, the people's feather robes and their turquoise. The haunting strain of their flageolets and the cadence of the chants came back to him. He recalled the incredible sight of a buffalo herd that blackened the horizon and the strength of an angry bull hoisting a horse on its horns. He could see the tierra nueva, the new land, in his wife's face. She was, he claimed, the only woman brought back from there. Still, in all the years since his return from the north, Troyano had found only three government officials, or so he said, who would admit the truth—that Spain had knowingly turned her back on a countless multitude of heathen souls, and in so doing had denied them the saving water of baptism.

Troyano wrote to the king from prison. He had been put away five years before, in 1563, for, in his words, "speaking the truth and remaining faithful to your royal crown against those who exceed their authority." As a partisan of New Spain's jealous second-generation, Troyano laid to venal, power-mad royal officials the corruption and confusion he saw around him. He begged Philip II to send honest judges and to restore military command to the second Marqués del Valle, son of Cortés. For himself, he sought a reprieve and the authority to implement reforms as protector general of Indians. And lastly, stressing the advantage of having a native wife, Juan Troyano wanted to join the, Marqués del Valle in an expedition "to settle that new country which Francisco Vázquez de Coronado discovered and add to our Holy Catholic Faith and the majesty of your royal crown another new world." [1] But Philip II, sobered by near civil war in New Spain, had no intention of allowing don Martín Cortés another chance. If new expeditions to Quivira were to be, they would spring not from a junta of disgruntled conquerors' sons, but from the frontier society emerging to the north, a society based on silver, slaving, and stock raising. Silver Strike at Zacatecas The spectacular failure of Coronado set the conquest of the far north back a lifetime. Realized wealth closer at hand, in the form of an incredibly rich silver strike, soon captured the fancy of New Spain. Quivira was forgotten. In September 1546, six months after Coronado was acquitted of all charges arising out of the Cíbola quest, a small party of mounted Spaniards with their ever-present Indian auxiliaries and four Franciscan friars camped at the foot of a distinctive hump-backed mountain a hundred and fifty miles north of Guadalajara. Capt. Juan de Tolosa was out pacifying Indians and prospecting. When he enticed some scared Zacatecos down the mountain, whose shape reminded someone of a hog bladder, the natives handed him chunks of silver ore. Within four years there had sprung up "a turbulent mining camp, full of prospectors from all parts of New Spain, who abandoned mines as quickly as they opened them up, jumped claims and neglected to register their workings." Fifty mine owners with mule-driven stamp mills and smelters and foundries, employing hundreds of Indians and black slaves, soon operated in the shadow of "La Bufa." The mines of Zacatecas represented more than princely wealth for Tolosa and his Basque cronies. It represented a commitment to bring within the Spanish empire the vast and harsh Gran Chichimeca, a region twice the size of "civilized" Mexico. It meant conquest and pacification by sedentary New Spain of the nomadic peoples who inhabited the high deserts and jagged sierras, and who by their ferocity and oneness with the environment more than made up for the sparsity of their presence. The Nomadic Chichimecas They were the "Chichimecas," a generic term of contempt picked up by the Spaniards from the natives of central Mexico meaning something like "dirty, uncivilized dogs." Far-ranging hunters and gatherers who planted maize only marginally, they presented the conquerors with a wholly different challenge. They refused to settle in pueblos. They refused to work voluntarily in stinking mines. The more the Spaniards learned of the Chichimecas, the more they despised them. At first the nomads struck at stragglers on the lonely roads between mining camps and at isolated ranches. They favored ambush and surprise hit-and-run attack. Their deadly accuracy, penetration, and rapid fire with bow and arrow awed Spanish soldiers. No Spaniard who survived ever forgot an attack by the screaming, stark-naked Guachichiles, their bodies painted grotesquely, their long hair dyed red. Stories of the excruciating, slow mutilation practiced on captives, of frenzied Chichimecas drunk on fermented juices, and of ritual cannabalism deepened the Spaniards' disgust.

War by Fire and Blood

For a generation and more, from roughly 1550 to 1585, most Spanish frontiersmen so abhorred the Chichimecas that they could think of no alternative to enslavement or annihilation. Even in the face of intensified Chichimeca hostility, the mining-slaving-ranching frontier advanced hundreds of leagues, creating pockets of Spanish settlement in the vastness between the two great coastal sierras. Towns were fortified, travel was restricted to armed convoys, and military men preached all-out war, guerra a fuego y a sangre, by fire and blood! In response, the Chichimecas banded together, at times under the effective leadership of indios ladinos, natives who had lived with the Spaniards and had learned their ways. They began to use horses. Now they attacked towns and wagon trains. While royal officials sought to impose peace on contentious Spaniards in central Mexico, they left the Chichimeca war pretty much in the hands of individual frontier captains. Not until the politically stable viceregency of Martín Enríquez, 1568-1580, did the government take the initiative. A general build-up, the founding of defensive towns, new regulations on slaving, plus unified command, financing, and supply—these measures, the hawks avowed, would rapidly bring the savages low. A chain, of frontier garrisons, or presidios, was set out along the major roads and manned by the first regularly paid and organized Spanish troops in New Spain. Still, jealous, sell-serving captains more interested in profits than military advantage kept taking natives, peaceful as well as hostile, and selling them as slaves. Despite the government's war effort, the Chichimecas struck at will. Mines lay idle, towns deserted. Not all the Spaniards in New Spain, wrote the disillusioned Enríquez to his successor, would be enough to conquer the wild men of the north. [2]

A Peaceful Alternative There was an alternative to military conquest—peace by persuasion. The famous Fray Bartolomé de las Casas had spent a lifetime preaching its virtues. But not until Spaniards on the embattled northern frontier began to admit that they were losing the war against their detested enemies could such an idea influence general policy. Long before that, however, certain vocal individuals spoke out against the war. One advocate of peaceful persuasion, a sort of frontier Las Casas, was Fray Jacinto "Cintos" de San Francisco, conqueror-turned-Franciscan lay brother. As Sindos de Portillo, soldier of Cortés, he had been rewarded with Indian tributaries, mines, and laborers. But he had renounced all that for the habit of St. Francis. Unlike many of his religious brethren, Fray Cintos refused to end his days at a comfortable convento among the sedentary Indians close to Mexico City. He looked instead to the pitifully neglected north and beyond to el nuevo México, the new Mexico, that mysterious land from which the Aztecs and their civilization allegedly had sprung, a place Coronado had somehow failed to find. In 1561, after he had been recalled temporarily from the tierra de guerra, the war zone, because of Zacateco hostility, the friar professed his commitment in a letter to Philip II written from Mexico City.

Had the viceroy provided a captain, fifty "good Christian" Spaniards, and a hundred peaceful Chichimeca auxiliaries, Fray Cintos believed, "without wars, killing, or taking slaves, the way might have been opened from here to Santa Elena and to the new land where Francisco Vázquez de Coronado went, and many leagues farther." This was a region so immense in the friar's mind that he envisioned a thousand or two thousand Franciscans engaged in the conversion of its inhabitants. The new Mexico would have been verified at last. But unfortunately the viceroy, occupied in launching Tristán de Luna y Arellano's ill-starred expedition to La Florida, could not spare the men. Fray Cintos appealed to the king. Like Las Casas, he inveighed against Spanish greed and cruelty toward the natives. He wanted the Chichimeca war and the killing stopped. He urged a peaceful campaign completely under the management of the Franciscans with the assistance of a God-fearing captain and a hundred moral Spaniards. In a related memorial to the king, Dr. Alonso de Zorita, justice (oidor) of the audiencia, or high court, of Mexico and the Franciscans' choice for the assignment, proposed to conquer the Chichimecas "by kindness, good works, and good example." If the Spaniards would but give these Indians the chance, asserted Zorita, they would settle down in towns, respond to the friars' gentle rule, and embrace the civilized agricultural way of life. In the long run, the expenses of such a policy would be less than the cost of waging war. But the Council of the Indies disagreed. Fray Cintos and Alonso de Zorita were a generation ahead of the times. [3]

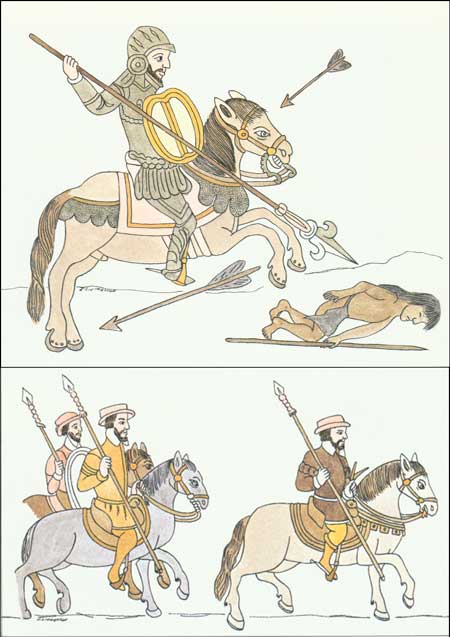

Franciscans on the Silver Frontier Under the cloud of guerra a fuego y a sangre, war by fire and blood, condoned by a majority of their Order, the few Franciscans in the north did what they could to instruct the Chichimecas. Fray Cintos and a handful of his brothers worked in the early 1560s alongside the young Francisco de Ibarra, founding towns like Nombre de Dios and Durango and exploring the sprawling, ill-defined province of Nueva Vizcaya. Lucas, the donado who had been with Coronado and who had witnessed the death of Fray Juan de Padilla, assisted the missionaries as interpreter and catechist. He must have filled old Fray Cintos' head with grand stories of the buffalo plains and populous pueblos like Cicuye. By 1566, the year Fray Cintos is supposed to have died from a scorpion's sting, Francisco de Ibarra had trekked back and forth across the rugged western Sierra Madre over much of Sinaloa and Sonora, the region that would later become the Jesuits' northwest missionary empire. Ibarra and Fray Pablo de Acevedo camped in the impressive Casas Grandes ruins in the northwestern corner of the present state of Chihuahua, just days short of the Pueblo Indians. Meanwhile east of the mountains, the mining frontier vaulted north up the "middle corridor" as Avino, Indé, and Santa Bárbara were staked out. The first of a cluster of settlements in the rich Parral mining district, Santa Bárbara developed slowly. Founded about 1567 by Ibarra's able associate, Rodrigo del Río de Losa, the community in the mid-1570s had a population of only some thirty Spanish families and a few natives. A serious labor shortage at first retarded the mining operation. The nearby Concho Indians, whom the Spaniards described as naked, lazy, and unattractive, were little inclined to work for Spanish masters. So the slavers pushed farther, provoking, hostilities and catching what hostiles they could. The mesquite and grasses of this entire foothill region proved ideal for grazing, and the valleys grew good wheat. The mining, stock raising, slaving frontier had reached present-day southern Chihuahua. [4] With a thousand arroyos leading north to the Río Conchos and then to the Rio Grande, it was now only a matter of time before Spaniards would appear anew to demand allegiance from the Pueblos. Renewed Interest in the Pueblos After decades of dealing with naked Chichimecas, friar and slaver approached the Pueblo peoples with new respect. They gratefully distinguished these rumored city dwellers as gente vestida, clothed people. A captured native, who told of "very large settlements of Indians who had cotton and who made blankets for clothing, and who used maize, turkeys, beans, squash, and buffalo meat for food," fired their imaginations, for different reasons. By the late 1570s, such reports, which seemed to confirm the allusions to rich northern cities in Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca's book, had emboldened a small company of veteran Indian fighters and prospectors. They had talked Fray Agustín Rodríguez, an overeager Franciscan lay brother, into petitioning the viceroy for a permit "to preach the holy gospel in the region beyond the Santa Bárbara mines." [5] Without the cover of evangelization, such an entrada would have been illegal. A native of Niebla, not far from where Columbus sailed in 1492, Fray Agustín had made his profession in 1541 at the Franciscans' Convento Grande in Mexico City. He had traveled widely among the Chichimecas "with the zeal of converting those barbaric infidels." In the Santa Bárbara area, this simple Franciscan evangelist fell in with frontiersmen Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado, Pedro de Bustamante, and Hernán Gallegos, an ambitious young paisano from Andalucía. When he learned of their willingness to join him in exploration, Rodríguez trudged back to the capital where he appeared before the viceroy in November 1580 and won approval to travel as a missionary north from Santa Bárbara. Moreover, he might take with him other friars and up to twenty men as an escort. Before he set out again for the frontier, he recruited two priests from the Convento Grande, Fray Francisco López, another Andalusian who went as superior, and Fray Juan de Santa María, a native of Cataluña well versed in the science of astronomy. [6] Rodríguez-Chamuscado Foray Before anyone had second thoughts, the little expedition trooped out of Santa Bárbara in the dry heat and dust of early June 1581. [7] Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado led the escort of mounted men-at-arms which, including him, numbered nine. Each had an Indian servant. The three friars took along half a dozen Indians and a mestizo. Driving several hundred head of stock, they followed the drainage of the Río Conchos northward to the Rio Grande, which they eventually called the Guadalquivir after the river that flows through Sevilla, birth place of both Fray Francisco López and Hernán Gallegos. These were the first Spaniards of record to approach the pueblos up the great river.

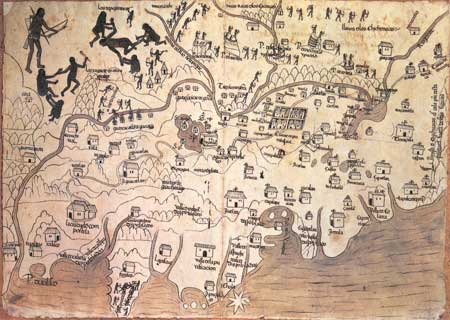

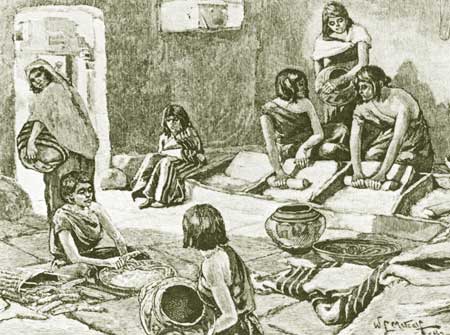

Although some of the naked peoples first encountered fled—for fear they were slavers—the Spaniards, according to Gallegos' account, inspired both respect and friendship by firing their arquebuses, giving cheap trade goods, and setting up crosses. By August 21, they were camped beside the first inhabited pueblo, some thirty miles below today's Socorro. Here they took possession of the province for Spain, naming it San Felipe in honor of the king. Again they had to entice the natives back from the hills. Traveling on through the Piro pueblos of gente vestida, who lived in tiered houses "white-washed inside and with well-squared windows," they exulted that surely they were being "guided by the hand of God." For the next five months this daring party of nine armed Spaniards with servants, friars, and livestock toured the pueblos. Because they were constantly reminded of the sedentary Mexican Indians—and because they were quite naturally maximizing the importance of their exploration—the members of the expedition began calling the province of the Pueblo Indians "the new Mexico." This time the name stuck. [8] Though the accounts are vague, evidently Sánchez Chamuscado and his men, who now threw off their guise of subordination to the Franciscans, proceeded eagerly up the Guadalquivir through the Tiwa pueblos. These Indians, so badly beaten by Coronado's army forty years before, received the Spaniards with cautious hospitality, as did the Keres farther north. From here, it would seem, the intruders were led on a quick "one-day" trip to see a pueblo which, with the possible exception of Ácoma, impressed them as more populous than any other. This probably was Coronado's Cicuye. Nueva Tlaxcala They did not say that they entered it, only that they saw and "discovered" it. It had, wrote Gallegos, "five hundred houses of from one to seven stories." In a later effort to ingratiate themselves with the king, the discoverers designated this prominent pueblo a royal town whose tribute, once New Mexico was pacified, would go directly to the crown. "Because of its size," they called it Nueva Tlaxcala after the capital city of Cortés' stalwart allies. The people of this new Tlaxcala indicated by signs that there were other pueblos farther on, but the Spaniards, short of horseshoes and gear, turned back. They made no demands of the inhabitants. [9]

The Death of Father Santa María The expedition had already begun to break up. Apparently just before or just after the discovery of Nueva Tlaxcala and a successful buffalo hunt, the astronomer Fray Juan de Santa María struck south from the Galisteo Basin with two native servants. He meant to report the soldiers' insubordination and to bring back more friars. The date was September 7, 1581. A few days later while he lay sleeping somewhere just east of the Manzano Mountains, the local natives dropped a big rock on him, crushing him in the manner they reserved for evil witches. [10] When the rest of the little band learned of Fray Juan's murder, they pretended not to understand. Instead, keeping up a bold front, the soldiers threatened to burn the pueblo of some Indians who had killed three horses and to execute the culprits. All that fall they explored the province, from the extensive salines of the Estancia Valley to the "great fortress" of Ácoma and the Zuñi pueblos beyond. Because of snow, they did not go to Hopi. The surviving two friars meanwhile had begun evangelizing the southern Tiwas of the Rio Grande. On January 31, 1582, at Puaray, the escort bid the Franciscans and their servants farewell—reluctantly, says Gallegos—and made for Santa Bárbara with the news of their discoveries.

The Escape of Gallegos The ailing Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado, bled by his companions with a horseshoe nail, died en route. The others rode into Santa Bárbara and woke up the town with a volley from their arquebuses. It was Easter Sunday, April 15, 1582. Early next morning, the aspiring Hernán Gallegos, taking all the pertinent documents and two of his comrades, galloped out of Santa Bárbara hell-bent for Mexico City. He barely eluded the grasp of local officials who sought to secure for the Ibarras this "new discovery which they are calling the new Mexico." [11] The second expedition of rediscovery, another small scale impromptu affair, resembled the first and grew out of the Franciscans' concern for their two brethren left defenseless among heathens two hundred leagues beyond Santa Bárbara. Again, an opportunistic frontier "captain" stepped forward to offer the friars his services. Again, dissension split the expedition once it reached New Mexico. And again, a handful of haggard adventurers returned full of wonders they had seen or imagined. [12]

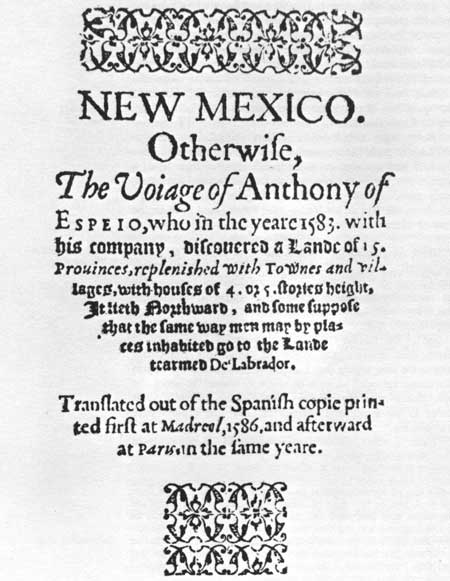

Espejo Offers His Services Antonio de Espejo, an enterprising Cordovan of some means, had spent a most active eleven years in New Spain. Lay officer of the Inquisition, cattle rancher and buyer, convicted accomplice in a murder case, don Antonio had removed to the frontier to avoid his sentence, a considerable fine. There he meant to recoup his fortune. As it happened, according to Espejo, one Fray Bernardino Beltrán of the Franciscan convento in Durango had volunteered to embark on a relief expedition to New Mexico. "As I was in that area at the time and had heard about the just and compassionate wishes of said friar and the entire Order, I made an offer—in the belief that by so doing I was serving Our Lord and His Majesty—to accompany the friar and spend a portion of my wealth in defraying his costs and in supplying a few soldiers both for his protection and for that of the friars he meant to succor and bring back." [13]

Despite some confusion about who had authorized the entrada and which friars should go, they got off from the Santa Bárbara district on November 10, 1582. A month later, just before heading up the Rio Grande, the dozen or fourteen soldiers, outfitted by Espejo, "elected" don Antonio their captain. Because the religious superior, who was supposed to catch up, did not, Father Beltrán remained the only friar. The whole party, counting the wife and three small children of one of the soldiers, cannot have added up to many more than forty. And they had begun their venture just as winter set in. Espejo cut a wider swath through the pueblos than Sánchez Chamuscado. By the end of February 1583, bluffing and cajoling, he had visited and "taken possession of" Piros, Tompiros, Southern Tiwas, and Keres. He had learned for sure that the Tiwas of Puaray had put to death Father Francisco López and Brother Agustín Rodríguez. Over the objections of Father Beltrán, who considered their mission accomplished, don Antonio resolved to see all the pueblos and potential mines he could. Among the Zuñis, where he found four Mexican Indians left behind by Coronado in 1542, Espejo jettisoned his dissenting chaplain and a number of others, pressing on to the awed Hopi pueblos with only nine soldiers. From there with four of them, he rode southwest over a hundred miles in search of mines. By the time the entire party reassembled at one of the Zuñi pueblos in early June, the breach was irrevocable. A mutiny miscarried. Seizing the royal standard, Espejo and eight loyal soldiers allowed the mutineers, including Father Beltrán, to depart for Santa Bárbara. Unencumbered, the captain now led his diminished column back to the Tiwa pueblos. The Ravage of Puaray News of what happened at Puaray spread. In the words of Diego Pérez de Lujan, the only eyewitness who recorded the event, "all the provinces trembled and received the Spaniards very well." The people of Puaray had taken to the hills, all but about thirty men on the rooftops who greeted Espejo's request for food with mocking. "In view of this," wrote Pérez de Lujan,

Ten days later, in early July, the terrible invaders appeared before Cicuye, which Espejo wrote "Ciquique" and Pérez de Lujan "Siqui." One of the soldiers, whose impressions were recorded the following year, considered this "the best and largest of all the towns discovered by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. It is set down on rocks, a large part of it congregated between two arroyos, The houses, of from three to four stories, are whitewashed and painted [inside?] with very bright colors and paints [or paintings]. Its fine appearance can be seen from far off." [15] Cicuye Intimidated The Spaniards camped two arquebus shots away, perhaps three to four hundred yards. When they asked for food, the natives indicated that they had none to spare. They pulled up their ladders and refused to come down. Pérez de Lujan thought the pueblo "must have contained about two thousand men armed with bows and arrows." Yet when Espejo and five soldiers, threatening to burn the place, entered and began firing their arquebuses "in the plaza and streets," nearly every one hid. Just then a Mexican Indian who had been with Coronado appeared, perhaps the "interpreter of these people" mentioned in one of the Sánchez Chamuscado accounts. He begged the Spaniards to desist. The people of Cicuye wished to be their friends and would give them food. "Thus a compromise was reached between the natives and the six Christians." After the Spaniards had withdrawn to their camp, the Indians brought them quantities of provisions, enough to last them all the way back to Santa Bárbara. Before they left, Espejo's soldiers abducted two Cicuye men. Ideally these Indians would learn Spanish and then serve as guides and interpreters in the pacification of their land, a common practice of the conquerors. One got away. The other, closely guarded, had no choice but to accompany the Spaniards down the Río de las Vacas—the Pecos—and back to the mines of Santa Bárbara, which they reached on September 10, 1583. [16]

A Native of Cicuye in Mexico City Bent on gaining for himself the royal contract to pacify New Mexico, don Antonio Espejo used his Indian captive from Cicuye to good advantage. He arranged in Mexico City that the native be placed under the tutelage of Fray Pedro Oroz, Franciscan commissary general for New Spain. A most compassionate teacher and scholar, Oroz was profoundly interested in the distant land where three fellow friars had so recently died martyrs. On April 22, 1584, the Franciscan wrote to the king urging that Espejo "be pardoned for a certain unfortunate episode" so that he might continue "to serve the Lord, disseminate Our Holy Catholic Faith, convert souls created in the image and likeness of God, and expand your royal domain." [17] Later in 1584, Father Oroz commented on the progress of his New Mexico pupil.

When he did receive the sacrament of baptism, this native of Cicuye took the name Pedro Oroz, Although Pedro died before the pacification of New Mexico finally got under way, one of the Mexican Indians he taught, Juan de Dios, came among the people of the great eastern pueblo in 1598 to preach the foreign gospel for the first time in their native language.

Castaño's Desperate Gamble After 1583, when Philip II instructed his viceroy in New Spain to find a man to pacify and settle New Mexico, competition intensified. Hernán Gallegos went to Spain and was politely brushed off. Antonio de Espejo, on his way to the royal court, died at Havana. Then while courtiers and northern frontier magnates contended for the prize, gouging at one another, don Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, a desperate would-be Cortés, gambled everything on getting there first, illegally. The law was explicit. The king had decreed in 1573 a whole set of ordinances designed to regulate expeditions of discovery and settlement. In part they represented the fruition at court of Las Casas' long advocacy of gentle persuasion. Use of the word conquest was banned in favor of pacification. Spaniards were to emphasize the wonderful advantages of Christianity, justice, and security that the natives might gain for themselves by peaceful submission. The horrible penalties of devastation and enslavement for those who refused—spelled out so graphically in the earlier requerimiento—found no place in the new legislation. Settlement was to be made without injury or prejudice to the Indians. [19] The ordinances of 1573 also reflected the financial straits of the Spanish monarchy. To encourage pacification without expense to the crown, the king fell back on granting exorbitant privileges to rich men. The feudal office of adelantado, a sort of lord of the march, as well as great entailed estates, hereditary fortresses, and the right to grant lands and Indian tribute—all this the ordinances held out to the prospective pacifier. Accordingly, as Philip reiterated in 1583, the Spanish colonization of New Mexico must be undertaken "without a thing being expended from my treasury." [20] The hope of such grand concessions—after the fact— must have filled the head of Gaspar Castaño de Sosa. An eager and resourceful frontier veteran, Portuguese by birth, Castaño had joined Luis de Carvajal in "pacifying" Nuevo León, that practically boundless region north of the Río Pánuco, east of Nueva Vizcaya, and extending "clear to La Florida." But it had gone sour. Carvajal's prolonged trial before the Inquisition on charges of being a crypto-Jew tainted his endeavors and his associates. Try as they might, neither he nor his roving minions discovered paying mines. Instead they resorted to wholesale slaving, bringing the added wrath of the viceroy down on Carvajal.

As lieutenant governor of Nuevo León, Castaño de Sosa tried to carry on for his jailed chief. But he had a plan of his own, based, he claimed, on permission implicit in the king's concessions to Carvajal. He would colonize New Mexico himself. To secure the viceroy's concurrence, Castaño dispatched agents to Mexico City. Viceroy Marqués de Villamanrique would have none of it. To the contrary, he cautioned his successor in 1590 to be wary of Castaño and his followers—"outlaws, criminals, and murderers—who practice neither justice nor piety and are raising a rebellion in defiance of God and king. These men invade the interior, seize peaceable Indians, and sell them in Mazapil, Saltillo, Sombrerete, and indeed everywhere in that region." [21] In the heat of June 1590, Capt. Juan Morlete rode into the dusty, unprosperous settlement of Almadén, later Monclova. He handed Castaño orders from the new viceroy, don Luis de Velasco II. They specifically forbade the lieutenant governor to take slaves or to set out for New Mexico without authorization. But Castaño, like Cortés seventy years before, chose to gamble on a dramatic fait accompli and the mercy of a grateful king. He ignored the viceroy. Taking matters wholly unto himself, Gaspar Castaño de Sosa resolved to move the entire settlement of Almadén to New Mexico—men, women, children, servants, dogs, oxen, goats, the lot. They were headed, he assured the nearly two hundred persons, for a land of mines and clothed, town-dwelling people. The king would reward them as he had rewarded the first colonists of New Spain. But they must make haste less some unscrupulous rival steal the march on them. The viceroy's blessings would overtake them en route. A Colony on the Move On Friday, July 27, 1590, the ungainly caravan moved out. A train of cumbrous, creaking two-wheeled ox carts, "una cuadrilla de carretas de Juan Pérez," imposed a crawling pace. These were to be the first wheeled vehicles seen in New Mexico. Strangely enough, the accounts of the expedition mention no friars, or even a secular priest. Perhaps the viceroy was right. Perhaps this lawless band of slavers had no use for missionaries. Castaño may have promised his colonists the benefit of clergy once they were settled in their new homes. Still, it is difficult to imagine a Spanish colony on the move without a priest.

Six weeks later, near today's Ciudad Acuña, they reached the Rio Grande, which they knew as the Río Bravo. Here a slaving party sent out earlier by Castaño rejoined the colony with a catch of some sixty male and female Indians. The lieutenant governor took his share, distributed the others among the soldiers, and made arrangements to ship the chattel south for sale. [22] By late October, after weeks of extreme hardship traversing the dry, broken terrain north of the Rio Grande, the scouts finally found their way down to the brackish water of the Pecos—Castaño's Río Salado—the river that would lead them north to the pueblos. [23] Just above present-day Carlsbad, Castaño convinced himself that he must be approaching the first settlements of clothed Indians. On December 2, he sent out his second-in-command, Maese de campo Cristóbal de Heredia, and at least eleven men-at-arms. They were to capture one or two Indian informants, but were not to enter any native town. Twice in the next two weeks, members of the advance party returned to report and to ask for provisions. Then on December 23, the lieutenant governor spied from a hill a lone figure plodding toward camp behind an exhausted horse without a saddle. Not long after, the rest of Heredia's woebegone troop dragged in. Three were wounded. They had found a pueblo. To a man they described it as large and fortress like. The inhabitants wore clothes of cotton and animal skins. The pueblo sat on a rocky ridge just west of the river the Spaniards were following. Curiously the author of Castaño's "Memoria"—probably secretary Andrés Pérez de Verlanga, if not the lieutenant governor himself—did not give this prominent pueblo a name. It was without a doubt Cicuye. The next year, 1591, after they had been among the Keres people, some of Castaño's soldiers began referring to the big eastern pueblo by an approximation of its Keresan name, the name by which it has been known to outsiders ever since—el pueblo de los Pecos. [24] Castaño's Advance Guard Humiliated Accounts of what happened to Heredia and his worthies at Pecos varied according to who was telling the story. The author of the apologetic Memoria, who endeavored to make Castaño out the hero and faithful vassal of the king, told how the advance party, cold, wet, and hungry, had chanced upon and followed a trail leading up from the river to the pueblo. Numbed by the freezing weather and snow, they sought shelter inside, ignoring the lieutenant governor's order to the contrary.

A clear case of Indian treachery worked on hungry but well-mannered Spaniards—thus the Memoria made it out. Cristóbal Martín, a member of Heredia's party who testified in proceedings against Castaño eight months later, saw the episode somewhat differently. He agreed that the Pecos had received them peacefully, "making the sign of the cross with their fingers," feeding them, and putting them up for the night. Next morning, however, when Heredia asked the Indians for maize "they brought so little that it was nothing. As a result, he ordered some of his men to enter the Indians' houses and remove some maize." At that, the Pecos "rebelled" and drove the Spaniards out of the pueblo. [26] Whatever the circumstances, the Pecos affair put Gaspar Castaño to the test, just as the Tlaxcalans had tested the iron Cortés. If he failed to win the submission of the first pueblo he faced, how could he hope to pacify a kingdom? Without provisions his people would starve. The Memoria records his response. Taking Heredia, twenty able men, seventeen attendants, and a supply of freshly slaughtered ox meat, don Gaspar rode forth to humble the Pecos. In the predawn cold and darkness, the lieutenant governor moved about camp reassuring his men. They must eat hearty and take courage. Because he intended to do the Indians no harm, he was confident that they would receive them well. No man was to make a move on his own. Everyone must obey orders. They were now only a short league from the pueblo. In hopes of finding an Indian who might carry word of the Spaniards peaceful intent, Castaño had Heredia send three men on ahead. Then on the last day of 1590 he and the others, "in formation with banner high," advanced on Pecos.

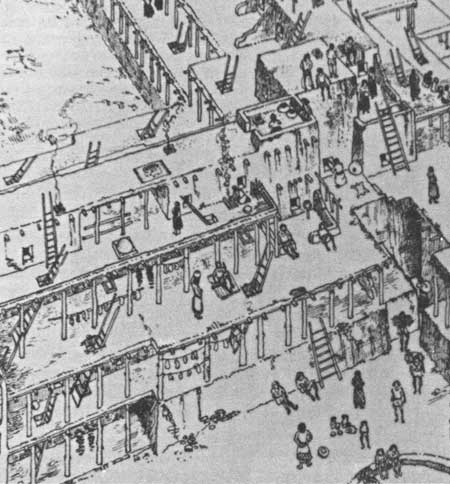

The Pecos obviously meant to fight. Fearing reprisal from the invaders after the Heredia episode, they had thrown up earth parapets atop the pueblo's flat roofs. The other more permanent fortifications, "the low ramparts, earthworks, and barricades which the pueblo has at the places most vital for its defense," puzzled the Spaniards. Later the Indians explained that they were at war with other peoples. Pecos Spurn Castaño's Peace Offer The lieutenant governor tried sign language. When no one ventured out of the fortified pueblo, he approached with Heredia and three others. The Indians shouted their derision. The women continued carrying rocks to the rooftops. The five Spanish horsemen circled the massive, tiered pueblo holding up knives and other gifts. As the clamor increased, the Indians let loose a barrage of arrows and rocks. For five hours, records the Memoria, Castaño sought in vain to placate the Pecos. Back in camp he put everyone on alert and had the horses rounded up. A group rode down and circled the pueblo trying to find out who the "captain" was. They claimed they saw him. Diego de Viruega dismounted and started to climb up a collapsed corner of the pueblo to give gifts to some seemingly less belligerent natives. But they would not let him. When the Pecos captain came over, the Spaniards gave him a knife and other goods, probably tossing them up to him. Still the Indians refused to parley. Castaño was losing patience. Taking his secretary in good Spanish legal fashion, the lieutenant governor started for the pueblo again. This time when the Pecos spurned his peace overtures, he had a writ drawn and witnessed. Then in council he asked his men what course he should take "since these Indians have utterly refused to listen to reason. With one accord they responded, 'Why does Your Grace wait on these dogs?'" The pueblo should be carried by force of arms. But was it not too late in the day, suggested Castaño, "If it is God's will to grant us victory," they reasoned, "there is time to spare." It was about two in the afternoon. On Castaño's orders, Heredia stationed two men on high ground north of the pueblo to report any Indians leaving. Once again the lieutenant governor appealed to the Pecos to lay down their arms. Just then a native woman came out on one of the overhanging corridors and threw ashes at him to the boisterous delight of the crowd. That did it. Castaño shouted orders. All the armed men mounted. Rodríguez Nieto fired a cannon shot over the pueblo and the others discharged a fearful volley from their arquebuses. Spaniards Attack

As the Spanish battleline advanced toward the walls, the Indians showered the horsemen with arrows and rocks, some hurled by hand and some with slings. Displaying fierce courage, the women kept on carrying rocks to the men on the roofs. Castaño, noting a house block on one side where there were no defenders, shouted at four soldiers to scale the wall and hoist up one of the little cannon. At the same time he attacked some Pecos who were harassing the climbers from behind parapets. With the four firing their arquebuses from the elevation, the lieutenant governor galloped back around to where the main force was assaulting the most heavily defended section of the pueblo. Blasting away with their firearms, the Spaniards expected the Pecos to break and run. They did not. "Each defended the post assigned to him without giving ground—a most incredible thing, that barbarians should be so astute." Ironically, a couple of Indian servants turned the tide in the Spaniards' favor. When Tomás and Miguel began shooting arrows at the Pecos, for some reason they panicked. The defenders began to fall back. While some of the invaders entered the rooms, others climbed up onto the roofs. Firing from the first high point taken by the Spaniards, Diego Díaz de Verlanga, with an incredible shot, felled a Pecos war leader who was bringing up reinforcements. The Indians withdrew. As Capt. Alonso Jáimez and his squad climbed from level to level, other soldiers covered them from below, bringing down at least three Pecos. The ascent was risky.

Suddenly the battle was over. Like Cortés, Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, utilizing horses, fire power, and steel, had humbled a foe that greatly outnumbered him. He had suffered very few wounded and apparently no dead. "As a sign of rejoicing and victory" he sent his ensign and the buglers to the top of the strongest house block to blow their trumpets. "Now, as the lieutenant governor walked through the pueblo with some of his men, no Indian threw a stone or shot an arrow. On the contrary, all tried by signs to show that they wanted our friendship, making the sign of the cross with their hands and saying 'Amigos, Amigos, Amigos.'" Not all the Pecos believed the fight had ended. One entire house block held out. The inhabitants who crowded the outside corridors of the other house blocks refused to come down. These corridors were "made of wood along all the streets, plazas, and house blocks. The natives get from one house to another by means of them and some wooden bridges from rooftop to rooftop where a street intervenes." When Diego de Viruega climbed up to greet the captain face to face, the natives ran from him, all but one old man. The Spaniard embraced him. Viruega scrambled down and the captain and people reappeared. By signs Castaño tried to convince them that they had nothing to be afraid of. In response some brought food and threw it down. When one Indian started to descend, the others restrained him. The lieutenant governor made them understand that he wanted the weapons, saddles, and clothing taken from Heredia returned. That, the native captain replied, was impossible. The clothing had been distributed among the people and everything but a few sword blades had been destroyed. Castaño would not be put off. He dispatched soldiers to apprehend, if they could, some Indians from the unyielding house block. Back in camp they might be made to reveal the truth about the missing gear.

It was getting dark. Asked a second time for the weapons and clothing, the Pecos threw down from the corridors a couple of sword blades without guards, one piece of thigh armor, and a few worthless scraps. Castaño told the native captain to have a further search made. He then returned to his camp where he learned that the soldiers had failed in their attempt to catch an Indian or two of those holed up in the one house block. It was almost impossible, they claimed, because "there were in this house block so many trap doors and hatch-ways and underground passages and counterpassages that it was a real labyrinth." Castaño ordered the maese de campo to post guards on the rooftops of this house block and horsemen around the entire pueblo to prevent an exodus under cover of night. Then the new Cortés slept.

A Graphic Portrayal of Pecos Next morning—New Year's Day 1591—in full dress regalia don Gaspar mounted his horse to inspect the pueblo he had won. The description preserved in his Memoria, taken with the details of the day before, is the best ever written of Pecos in its heyday.

Pecos Desert Homes Because the Pecos returned a few more worthless bits of the equipment lost by Heredia and his men, Castaño decided to remove most of the guard that night as the Indians had requested. At dawn the next day in the crystal cold air, the pueblo seemed unusually still. The Spaniards began a house by-house search. Not a soul—man, woman, or child—could be found. The entire population had vanished. Their tracks in the snow should have been easy to follow. Instead, Castaño waited for them to come back. They did not. A further search of the houses turned up more bits of Spanish gear, all of it smashed to pieces. Taking a portion of maize, beans, and flour from each house—in all, claims the Memoria, no more than twenty-one fanegas—the lieutenant governor ordered eight soldiers and eight or ten attendants to transport these provisions to the half-famished main camp downriver. Four days later there was still no sign of the Pecos. "Therefore the lieutenant governor resolved to break camp so that the Indians might return to their pueblo. He felt very sorry for them because they had left their homes in the bitter cold of this season, with its winds and snows, so incredibly severe that even the rivers were completely frozen."

Because he could not hope to get the carretas through the narrows along the river south of Pecos, the lieutenant governor hoped to find other more accessible pueblos where the entire expedition could wait out the winter. He was also prospecting. When he had shown the Pecos ore samples, they pointed west and north, perhaps intentionally in the direction of the Tewa pueblos. On Epiphany, January 6, 1591, the Spaniards made ready to leave deserted Pecos. Castaño told Maese de campo Heredia to conceal four men with good horses inside the pueblo. If they could capture a few Indians, these might be convinced to bring back the others. But just then a couple of natives approached. They were grabbed and brought before Castaño, who plied them with gifts. In their presence, he had a tall cross erected "giving them to understand what it meant." He asked his secretary to draw up a proclamation of amnesty in the name of the king, handed it to one of the Indians, and told him to take it to the Pecos captain. Then, with the other Indian "contentedly" leading the way, Gaspar Castaño and company departed Pecos.

Two leagues later they came upon another Indian, reportedly a son of the Pecos cacique. Taking him as a second guide, the party fought through Glorieta Pass in a snowstorm. Probably these two Pecos led the invaders northwest toward the Tewa pueblos for good reason. Their own people had likely taken refuge among the Tanos in the Galisteo Basin, southwest of Pecos, motive enough to steer the Spaniards in another direction. Moreover, there was, it would seem, no love lost between Pecos and the Tewas. [27]

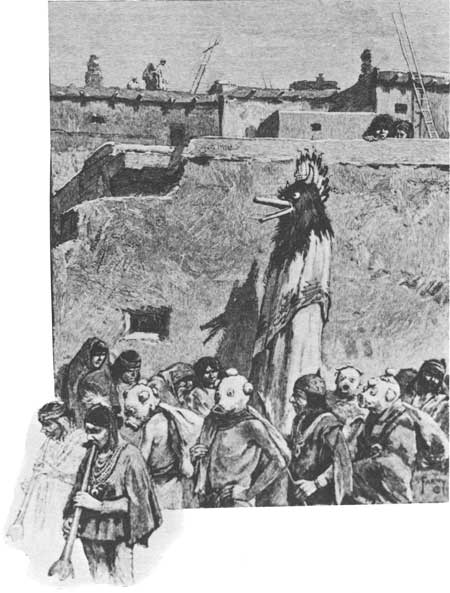

Castaño Tours the Pueblos As he traveled first through Tewa country and then back by some of the Keres and Tano pueblos, no one dared oppose the conqueror of Pecos. Only once, at a large northern pueblo, possibly Picuris, did the inhabitants show signs of resisting. But Castaño chose not to force entry, vowing instead to come back later. The Spaniards had it their way everywhere else. At each pueblo, they set up tall crosses to the blare of trumpets and arquebuses, whereupon the lieutenant governor, with all the pomp he could muster, took possession in the name of Philip II. As the awed natives rendered obedience in the manner shown them, he appointed a governor, a justice (alcalde), and a constable (alguacil). Late in January after a month's absence, Castaño reappeared at the main encampment on the Pecos River. Remobilizing the benumbed colony, he now led it westward toward the closest of the Tano pueblos. More snow fell and carts broke down. Once among the Tanos, who shared of their stores like it or not, the colonists revived. Meanwhile their leader rode back to settle accounts with the Pecos. Don Gaspar had taken Pecos in battle but he had yet to receive the obedience of its people. Approaching again on March 2, he deployed Maese de campo Heredia on a commanding elevation to prevent a second exodus. This time he found the Pecos "confident and very much at ease." This time they made no show of war.

With the crowd milling around them, the Spaniards made camp "next to the houses." This time the natives volunteered quantities of maize, flour, beans, and "some of their trifles." The invaders accepted.

The Viceroy versus Castaño While Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, the outlaw colonizer, boldly met the challenges of the trail, the weather, and the Pecos, the viceroy of New Spain moved against him. Within days of the colony's unauthorized departure for New Mexico, a courier had galloped south with a full report from Castaño's "old rival" Juan Morlete of Mazapil. Viceroy Velasco acted swiftly. On October 1, 1590, he instructed the eager Morlete to mount a military counter-expedition. "Since, as I have said, the primary purpose of this expedition is to stop Gaspar Castaño, it is important that you do not come back without him and his men, using all suitable care and taking every precaution." [29]

In the viceroy's mind, a great deal more was involved than the letter of the law. He and his predecessor had reversed the long-standing policy of war by fire and blood on the northern frontier. Through diplomacy, expanded missionary effort, placement of sedentary Indian colonies, and large-scale government subsidies, they had brought unprecedented peace to the Gran Chichimeca. The cost of supplying once-hostile wild men with maize and beef had proven far cheaper than war. Now as Velasco sought to consummate the peace, an obstacle stood in his way—the unscrupulous self-serving Indian slaver. [30]

Rightly or not, Velasco put Gaspar Castaño in that category. Moreover, when the accused Judaizer and slaver Luis de Carvajal died in Mexico City, the viceroy transferred his ire to Castaño, Carvajal's lieutenant. From his vantage point in the viceregal palace, he saw the members of Castaño's illegal entrada as "vagabonds who had joined him and indeed all the riffraff left over from the war against the Chichimecas. . . . And since I regarded as extremely improper and injurious the damage these men were doing in capturing and selling Indians, and was mindful of the danger involved, I decided to send Capt. Juan Morlete in pursuit of the malefactors," [31] Quashing Castaño, as the viceroy saw it, would put an end to the whole sordid business of Nuevo León. Even as the unknowing Castaño celebrated his pacification of Pecos in early March 1591 with trumpets and volleys, Morlete, Fray Juan Gómez, and forty soldiers were closing on their prey. The confrontation occurred at Santo Domingo. Castaño had moved his colony to this Keres pueblo on March 9 and 10; then a couple of days later he had set out with twenty men "in search of some mines and a people he had not yet visited." Toward the end of the month, just hours before the lieutenant governor got back, Morlete reached Santo Domingo. Castaño Arrested Castaño rode up at a gallop, dismounted, and embraced his rival. He asked what brought him to New Mexico. All of them, replied Morlete, were under arrest. His orders from the viceroy called for him to escort the entire colony to Mexico City. Castaño demanded proof. When he had seen and heard the orders for himself, he yielded without a struggle. Unlike Cortés, he had discovered nothing in this new Mexico with which to bribe his rival's force. A goodly number of his own people were sick of the venture and ready to desert him. Thus Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, the would-be master of New Mexico, commanded that his own banner be lowered. He then submitted to the leg irons. Readily conceding that he was a miserable sinner in the eyes of God, Castaño never would admit willful crimes against the king. He began his defense en route. "I insist," he pleaded in a letter to the viceroy, "as God is my witness, that if I have indeed erred I did so in sincere reliance upon authority granted by His Majesty's order to Luis de Carvajal as governor and captain general of the kingdom of Nuevo León." As for the reports of slaving among peaceful Indians, these, Castaño averred, were malicious lies told by envious and hateful rivals. Tried before the audiencia of Mexico on charges of "in vading lands inhabited by peaceful Indians, raising troops, entry into the province of New Mexico, and other acts," Gaspar Castaño was found guilty and sentenced to six years' military service in the Philippines. He sailed in 1593. Later, word was received in Mexico that the ill-starred don Gaspar had died at the hands of mutinous Chinese galley slaves on a voyage to the Moluccas. Only then did the results of his appeal to Spain arrive. He had been acquitted of all charges. [32] By the closing decade of the sixteenth century, the precedents were set, not only in the heartlands of Mexico, but in the far north as well, A half-century of frontier experience—of first fighting then buying off the Chichimecas—had given shape to the familiar institutions of the next centuries: the mining-hacienda complex, the presidio, the frontier mission, and peace by purchase. Both the massive church Fray Andrés Juárez built at Pecos in the seventeenth century, and the peace with the Comanches signed there by Gov. Juan Bautista de Anza late in the eighteenth had their roots deep in the century of Fray Cintos de San Francisco and the Ibarras. Men of great wealth, products of the silver frontier, vied for the New Mexico contract. Viceroy Velasco bided his time. "It is readily apparent," he advised the king, "that no one will care to enter into a contract for this venture without assurance of great advantages and profit, or without the aim and prospect of encomiendas and tribute from the Indians." Because he rightly presumed that the Pueblo Indians were New Mexico's greatest asset, he suggested that the king himself finance their conversion. [33] But crotchety old Philip was in no mood, European wars cost mighty sums. The viceroy must seek a rich and suitable Christian gentleman. Whether the king of Spain chose to call it conquest or pacification, New Mexico's time had come.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||