Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

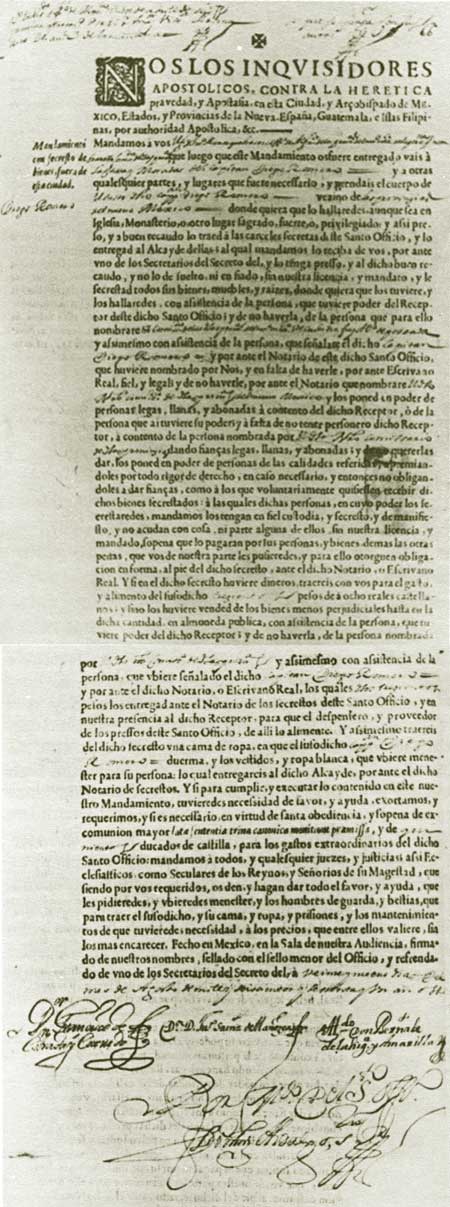

The Inquisition as a Weapon of the Friars Back in the early 1620s, the unshrinking Fray Esteban de Perea, locked in close combat with Gov. Juan de Eulate, had appealed for help to the tribunal of the Inquisition in Mexico City. The Holy Office had responded positively, appointing outbound Custos Alonso de Benavides as its first comisario, or agent, for New Mexico. The Inquisition's presence, comforting to the devout and dreadful to the accused, was broadcast, and reaffirmed periodically, by the formal reading of an Edict of the Faith. For the unburdening of their consciences, anyone with information regarding thought, word, or deed against the Holy Mother Church must come forward and confess it. The local agent had authority to investigate alleged threats to the purity of the Faith by members of the Hispanic community, to summon witnesses and record their testimony, and to recommend and, upon receipt of approval, to execute the arrest and deportation of the accused to Mexico City for trial before the tribunal. Whether the Inquisition's presence in this rude, superstitious, ingrown frontier society made New Mexico a better place to live or not, it did put a formidable weapon in the hands of the friars. Eulate had left the colony just in time. The governors who succeeded him had cooperated with the friars more or less. Agent Benavides devoted most of his considerable energy to expanding the mission field. Then, during the thirties when church-state relations had deteriorated once again, when the friars really needed the muscle of the Inquisition, local agent Perea grew old and died. The rough and merciless Governor Rosas had taken every advantage. In the sixties, it would be different. Another governor who shared Rosas' greedy expectations and his disdain for the missionaries would find himself shackled in a wagon bound for the prison of the Inquisition in Mexico City.

Because they were considered perpetual minors in the Faith, Indians who retained their Indian identity were exempt from prosecution by the Inquisition, which was not necessarily a blessing. Mission discipline, depending on the friar in charge, could be much more arbitrary and even sadistic. Serious cases involving Indians—apostasy, heresy, and the like—went not to the Holy Office, but to the bishop, or in New Mexico, to the Franciscan prelate. In a society that considered the church an arm of the state and vice versa, crimes against the Faith and treason commingled. In cases of alleged Pueblo sedition, it was the royal governor, generally with consent of the friars, who sentenced them to the gibbet or slave block. The Pecos may not have understood the workings of the Inquisition, but it touched their lives. Several times during the 1660s, the agent resided at Pecos. Witnesses came and went. Two important Spaniards whom they knew all too well, their encomendero and a plains trader, were arrested and carted away. Then one night, the royal governor rode out to Pecos, entered the convento with armed men, and removed the agent to Santa Fe. Such acts cannot have enhanced the Pueblos' respect for their contentious, overbearing masters. The meticulous, sometimes shocking, and often wearisome records of the Inquisition provide a keyhole view of society in seventeenth-century New Mexico. Seen from there, 1680 comes as no surprise.

Governor López versus Ramírez Don Bernardo López de Mendizábal, governor of New Mexico from 1659 to 1661, was a petulant, strutting, ungracious criollo with a sharp tongue and enough education to make himself dangerous. Even before the caravan left Mexico City, don Bernardo and Fray Juan Ramírez, another contentious criollo, had quarreled over their respective jurisdictions. Ramírez, appointed procurator-general of the New Mexico custody to succeed the illustrious Fray Tomás Manso, had also been elected custos. As the wagons rumbled north, Franciscan prelate and royal governor carried on their own petty war. Ten of the twenty-four friars bound for the missions deserted in protest. López blamed Ramírez and Ramírez blamed López. Both would have their day in court. Both, within three years, would stand accused before the Inquisition. [1] Arriving in mid-summer 1659, Governor López de Mendizábal took over from Juan Manso while Custos Ramírez relieved Fray Juan González. Ex-governor Manso, younger brother of Fray Tomás, had got on tolerably well with the Franciscans and had aided them in their efforts to found missions in the El Paso area. As was customary, he remained in the colony for López to conduct his residencia. Ex-custos Juan González, who had been in New Mexico since at least 1644, stayed on as a definitor of the custody and as guardian at Pecos. Coincidentally, Father González and the Manso clan—Fray Tomás, veteran head of the mission supply service, provincial, and bishop of Nicaragua; his brother Juan, governor from 1656 to 1659; and their nephew Pedro Manso de Valdés, later lieutenant governor—all were born in the tiny, picturesque Asturian seaport of Luarca on Spain's windblown north coast. In America, nineteen-year-old Juan Gonzaléz had pronounced his religious vows on the feast of St. John Chrysostom, January 27, 1624, at the convento in Puebla. With studies and ordination behind him, he must have ridden north with his paisano Tomás Manso in one of the caravans of the 1630s. He was at Santo Domingo in September 1644 to sign the missionaries' fervent defense of their conduct. Although he may have served during the 1640s or 1650s at Pecos before his term as custos, Gonzaléz did nothing indiscreet or outstanding enough to inscribe himself in the scant records that survive. [2] The friars' alleged snubs of López de Mendizábal and the governor's refusal to receive Custos Ramírez in Santa Fe as ecclesiastical judge ordinary set the tone of church-state relations for the next two years. What the governor did in the name of Indian reform, and in his own economic best interest, the Franciscans saw as open interference in mission affairs. On his visitation of the colony, which by law every governor was supposed to make, López sought to win over the Indians at the misionaries' expense. The governor inspected Pecos, probably during the "trade fair" in 1659, but details are lacking. At nearby Galisteo in the presence of ten Spaniards, among them Pecos encomendero Francisco Gómez Robledo, don Bernardo grilled the Indians, men and women, one by one, under pain of death, about the personal life and habits of the missionary. "I am certain," protested Fray Nicolás del Villar, "that no prelate of mine would have made such a rigorous examination of any religious, and with so many and such exquisite questions, as His Lordship made of each of the natives." [3] López Opposes Unpaid Labor More serious than his effort to defame the friars themselves was López' attack on their use of free Indian labor. Early in his administration, the governor by decree raised the standard Indian wage from half a real per day to one real plus food. He then tried to impose it on the missionaries, who had long enjoyed the services of mission Indians without paying wages as such, In their defense, the Franciscans cited a 1648 decree by Gov. Luis de Guzmán y Figueroa, based on a royal cedula, exempting from payment of tribute the pueblo governor as well as natives employed "in service to the churches and divine worship," namely "an interpreter, a sacristan, a first cantor, a bellringer, an organist where there was an organ, a shepherd, a cook, a porter, a groom." The reference to organists seems to confirm that the órganos reported earlier in the 1640s at Pecos and other missions were indeed instruments and not merely choirs skilled in polyphonic chant. Up to the time of López, the friars had claimed these ten exemptions for mission staff. [4] According to much-abused Father Villar at Galisteo, the cavalier López relieved the women who baked the friar's bread and told them never to bake for him again. The royal governor then ordered the other servants of the convento to pay tribute—tanned skins and mantas—"for no other reason than having served." When López found out that Villar, who had been at Galisteo only a year struggling with the Tano language, still relied on an interpreter "he sent the latter off to a ranch to break young bulls." Next López had forbidden any Indian to carry a message for the friar and had removed the native fiscales of the pueblo, ostensibly because only the king—not the missionaries—could name them. As a result, the friar's hands were tied, he had no one to bake his bread, no way to preach to the Indians or impose discipline. In short, his ministry was doomed. [5] To counter the charges he knew the Franciscans were lodging with the viceroy, Governor López de Mendizábal set down charges of his own against them. They ran the usual gamut, from oppression of mission Indians and wanton misuse of their quasi-episcopal powers to blatant clerical immorality. When Franciscan Vice-custos García de San Francisco excommunicated Nicolás de Aguilar, López' heavy-handed agent in the Salinas district, the governor challenged his authority to act as anything but a parish priest to the laity. At López' bidding, witnesses gathered round. Concerning the arbitrary and contemptuous use of excommunication and absolution, Juan González Lobón, whom the friars considered a buffoon, testified that Fray Juan González of Pecos had absolved him "with some quince bars." The witness claimed that he was not informed why he had been excommunicated. Nevertheless, the friar fined him thirty cotton mantas for which González Lobón gave a draft on his encomienda receipts "to rid himself of his vexation." [6] The Alcaldes Mayores To squeeze the colony for every manta and every last fanega of piñon nuts he could, López de Mendizábal relied on his appointed district officers. In New Mexico, the alcalde mayor, sometimes called a justicia mayor, who presided over local affairs in one of the colony's six or eight districts, or jurisdicciones, served unsalaried and at the governor's pleasure. He administered petty justice, settled minor disputes over land and water, supervised the use of Indian labor, rallied the local militia, and helped the friars maintain discipline in the missions—any or all of which could be turned to his own profit and that of the governor. An alcalde mayor could be the missionary's best friend or his worst enemy. In the Salinas missions, the friars branded Nicolás de Aguilar the Attila of New Mexico. [7] López de Mendizábal's man in the Galisteo (Tanos) district, which also included Pecos, was Diego González Bernal. He, like Aguilar, carried out his governor's orders with gusto, as in the case of alleged fornication against the old friar at Tajique. It is not known how early an alcalde mayor was appointed for the Galisteo-Pecos jurisdiction. Back in the mid 1640s, the friars had accused Governor Pacheco of appointing such officials in most of the mission areas where only Indians lived, "a thing never done before." Although González Bernal surely had predecessors as "alcalde mayor and military chief of Galisteo and its district," their names are lost. In the documentation for López de Mendizábal's residencia, there is a packet of two dozen letters from him to González Bernal. The governor wrote of his stormy relations with the friars, of competition with them for Pueblo Indian labor, but mainly of day-to-day business affairs. Multiplying this correspondence by the number of the governor's other agents and appointees gives a fair idea of his economic vise grip on New Mexico. [8]

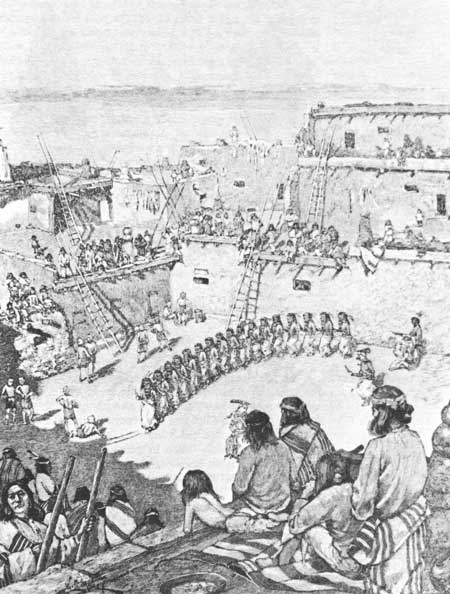

The Governor and Kachina Dances Another of the duties of an alcalde mayor was to announce in all the settlements and pueblos of his district, through an interpreter where necessary, the decrees of the governor in Santa Fe. When, to the horror of the friars, López de Mendizábal decreed that the Indians should resume their ceremonial dances, González Bernal did his duty. According to the missionary at Galisteo, the Tanos of that pueblo, San Cristóbal, San Lázaro, and La Cíenaga were only too happy to oblige with "some evil and idolatrous dances called kachinas, from which idolatry followed in these pueblos." Even worse, a rowdy group of Spaniards "had got themselves up in the manner of the Indian kachinas and had danced the dance of that name at the pueblo of San Lázaro and afterwards did the same at their house next to Galisteo." One of them danced in a shocking state of undress. At Pecos, Fray Juan González reported no such brutish goings on. [9]

López under Fire For Bernardo López de Mendizábal, 1660 was the year his fortunes turned. While he and his men kept on extorting a goodly profit in New Mexico, the charges against them were piling up in Mexico City. The first reports critical of the López administration reached the viceroy early that year. He sent copies over to the Holy Office. In the spring, the friars' special messenger and Custos Ramírez, whose supervision of the supply service required him to return to the viceregal capital with the wagons, both testified before the inquisitors against López' regime. Other messengers arrived with atrocity stories: missionaries dishonored and persecuted; Indians, undisciplined, reveling in the old pagan rites "with costumes, masks, and the most infernal chants," goaded by Spanish Christians. If relief did not come soon, one friar told the Holy Office in September 1660, the Franciscans would withdraw from New Mexico. And it was not only the Franciscans. In an effort to make capital out of former governor Juan Manso's residencia, López de Mendizábal had stalled and then locked up his predecessor. But Manso, with the aid of disenchanted New Mexicans, had escaped. Within four months, he stood before the tribunal of the Inquisition. López, meanwhile, sent Sargento mayor Francisco Gómez Robledo off to Mexico City with a defense of his actions and a packet of countercharges against the dictatorial, scandal-ridden Franciscans. Unfortunately for don Bernardo, messenger Gómez never made it. By the end of 1660, the Franciscan superiors had chosen as custos of New Mexico a tough young veteran who had served there during the mid-fifties but who had left before López and his gang took over. He was Alonso de Llanos y Posada González, who signed himself Fray Alonso de Posada. The Holy Office made him its comisario and charged him to carry out the most thorough investigation. The viceroy, who normally would not have appointed another governor for a year, yielded to the outcry from New Mexico and did so in 1660. He chose don Diego Dionisio de Peñalosa Briceño y Berdugo, an accomplished rogue. Together, Posada and Peñalosa would make don Bernardo pay more dearly than he could ever have imagined. [10] Enter Posada and Peñalosa Custos Posada reached the colony first. On May 9, 1661, as agent of the Inquisition, he began hearing formal testimony that quickly opened his eyes. On May 22, he forbade kachina dances and ordered the missionaries to seize every mask, prayer stick, and effigy they could lay hands on and burn them. This they did, to sixteen hundred such objects by their own count. Still, Custos Posada managed to stay out of López' reach until Governor Peñalosa arrived three months later. Almost immediately Peñalosa announced López' residencia. Posada published an Edict of the Faith. The ex-governor stayed away. He said he was ill. [11] While still in office, López had sacked Alcalde mayor Diego González Bernal. Something had happened between them. Earlier, González had been a loyal servant, dutifully accusing the friars in the Tano missions of driving Indians out of church and refusing the sacraments to Spaniards. Yet during his residencia, the ex-governor would call González "a man with no sense of responsibility, a mestizo by birth." López had even thrown González Bernal in the public jail once "because he exceeded a commission I gave him to put Jerónimo de Carvajal in possession of certain lands." So upset did the prisoner become that he pretended to have lost his mind, whereupon López had ordered him placed in the stocks "to restrain him." Furthermore, López had banished from the capital Diego's kinswoman Catalina Bernal "for being a scandalous person and the bawd for her daughters."

Don Bernardo had experienced no better luck with his next appointee, Antonio de Salas, whom he removed almost immediately "because of the uproars he caused there and for being a comrade of the friars." Salas, also encomendero of Pojoaque, had fallen out with López when the governor made him raze the house he maintained inside that pueblo. [12] The third alcalde mayor of Galisteo and its district in less than a year was Jerónimo de Carvajal, thirty years old, born in the Sandía district, and owner of the estancia, or ranch, of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios de los Cerrillos, not far from the present-day town of Cerrillos. It was common knowledge that Carvajal's comely young wife Margarita Márquez had been the mistress of Gov. Juan Manso. [13] López' Residencia Proclaimed On Friday afternoon, September 30, 1661, at the bidding of Alcalde mayor Carvajal "all the captains and the people" of Pecos assembled in the pueblo's plaza mayor to hear another proclamation. Carvajal and some other Spaniards had ridden over from Galisteo, Francisco Jutu, a Pecos "conversant in the Spanish language," stood before the crowd as crier and interpreter. Through him they learned that for a period of thirty days any person with complaints or claims, civil or criminal, against former governor López de Mendizábal or his subordinates should appear before the new governor in Santa Fe. Their grievances would be noted, justice would be done, and damages would be compensated. All this the Pecos had heard before. [14] One of the two witnesses who attested the proclamation at Pecos that afternoon was Diego's younger brother, Antonio González Bernal. He had been named by Governor Peñalosa to act as protector de indios during the López residencia. His job was to compile and present all the Indians' claims against the ex-governor. The Pecos submitted theirs. López still owed them one hundred pesos for "one hundred parchments and fine tanned skins" at a peso each. He also owed them for seven tents of fine tanned skin, worth eight pesos each, or fifty-six pesos. Nor had he paid them for "a great quantity of piñon nuts." They could not remember exactly how many fanegas. They asked that Sargento mayor Diego Romero, who had taken delivery of the nuts on López' account, state the quantity. [15]

In all, Governor Peñalosa received more than seventy formal petitions of complaint against his predecessor. Fray García de San Francisco presented the friars' claims, without ever mentioning Pecos. Diego González Bernal as attorney general denounced his former patron on behalf of the Hispanic community, and Antonio González Bernal spoke for the Indians. A parade of individuals added claims of their own. Out of all this, Peñalosa drew up a thirty-three-count indictment against the ex-governor. López answered, as was customary, count by count, denying most of the allegations, identifying his enemies, and explaining the motives for their perjury. Both Father San Francisco and Diego González Bernal recommended to Governor Peñalosa that he confine López. He did. [16] In his arrogance, don Bernardo had alienated virtually everyone except Fray Juan González of Pecos. In the hundreds of pages of impassioned testimony, there is hardly a mention of ex-custos González or his mission. When summoned to testify before Father Posada, the even-tempered Fray Juan made it very clear that everything he reported against López and his men was hearsay. It was González whom the imprisoned former governor asked to hear his confession and administer communion. López had sent one of his four guards to Custos Posada during Lent in 1662 requesting the services of a priest. Fray Nicolás del Villar had balked. The confined former governor did not want Fray Nicolás de Freitas, guardian at Santa Fe and fast friend of Governor Peñalosa, for "plenty of reasons." After those two, Father González was closest. Besides, Posada had delegated him to preach the Santa Cruzada and he would be in Santa Fe anyway. López knew that Fray Juan would not refuse him even though it might strain his charity. The guardian of Pecos, unlike the other friars, had not embroiled himself in the affairs of the López administration. For that reason, said don Bernardo, "he always was and is my choice." [17]

Inquisition Closes In on López While López de Mendizábal languished in confinement, his accusers drew the noose tighter and tighter around his neck. The resourceful Governor Peñalosa wanted to ruin his predecessor without assistance. But it was Father Alonso de Posada, brandishing the terrible authority of the Inquisition, who really brought low the unrepentant don Bernardo. The Holy Office in Mexico City had already ordered the arrest of three prominent members of the López camp—the notorious Nicolás de Aguilar, alcalde mayor of the Salinas district; Sargento mayor Diego Romero, former alcalde ordinario, or municipal magistrate, of Santa Fe; and Sargento mayor Francisco Gómez Robledo, holder of the Pecos encomienda and several others. The arrest of a fourth New Mexican, Cristóbal de Anaya Almazán, was left up to the discretion of Agent Posada. By the spring of 1662, Posada had these orders in hand. Their bearer was none other than ex-governor Juan Manso, spoiling for the chance to square accounts with López de Mendizábal. Another action by the Holy Office made Manso alguacil mayor, chief constable, of the Inquisition in New Mexico and charged him with carrying out the arrests. Thus while a similar fate for López was being sealed in Mexico City, the doughty local agent and his constable moved against the four marked New Mexicans. [18] Arrest and Ordeal of Gómez Robledo It was still dark. The first thin light of dawn barely shown behind the mountains to the east. Francisco Gómez Robledo, like nearly everyone else this early Thursday morning, lay in bed asleep. Then something intruded, a heavy banging. It could not have been later than five. He stumbled to the door. "Open," came the command, "open in the name of the Holy Office!" He did. Outside in the chill air stood Alguacil mayor Juan Manso, his nephew Maese de campo Pedro Manso de Valdés, and Father Posada's zealous notary Fray Salvador de la Guerra. Oh, God. They presented the order for his arrest and entered. After he had put on his clothes, "and with hat and cloak," they led him out of his house "which faces on the corner of the royal plaza of this villa" and across to a cell in the Franciscan convento. Guards were posted at door and window. Alguacil Manso ordered Gómez' possessions attached, including his Santa Fe house, his estancia of San Nicolás de las Barrancas downriver in the vicinity of today's Belen, and his encomiendas. He ordered leg irons and chains placed on the prisoner. He told him to designate a person of his choice to assist in the attachment of his property. Gómez named his brother-in-law and compadre Maese de campo Pedro Lucero de Godoy. Outside, it was getting light this May 4, 1662. [19]

A bachelor in his early thirties and the father of two natural children five and six years old, Gómez Robledo would not learn the charges against him for more than year. Yet he must have known that someone had whispered the ugly lie that he was a Jew, just as they had about his father. Born in Santa Fe about 1629, the first son of Francisco Gómez and Ana Robledo, he had been baptized by Fray Pedro de Ortega and confirmed by Fray Alonso de Benavides. On both occasions Gov. Felipe Sotelo Osorio stood as godfather. The elder Francisco, a Portuguese in the service of the Oñates, had held subsequently every office of importance New Mexico had to offer, even that of alguacil mayor of the Inquisition. Until his death at age eighty in 1656 or 1657, Francisco Gómez had been the colony's strongest defender of royal authority as vested in the governor. Cast in the same mold, Francisco the younger, a heavy-set individual with straight dark chestnut hair, had begun soldiering at age thirteen and had served as councilman and municipal magistrate of Santa Fe. He had carried out numerous commissions for the governors, and like his father had more than once stepped on the friars' toes. His knowledge of the Indian languages served him well. During López de Mendizábal's visitation, Gómez Robledo had stood close at hand. According to some, it was he who counseled the governor that kachina dances were simply not as diabolical as the missionaries avowed. When everyone else backed away from the assignment, it was Gómez Robledo who had ridden for Mexico City with López' defense of himself. That he had been forced at Zacatecas to surrender the dispatch to the northbound Peñalosa was not, he maintained, his fault. In 1662, don Francisco, pater familias of the large Gómez clan and pillar of the Hispanic community, held the rank of sargento mayor and served as mayordomo of the religious confraternity of Nuestra Señora del Rosario. [20] That same Thursday, in the presence of Pedro Lucero de Godoy, Alguacil Manso and the others inventoried Gómez Robledo's house on the plaza. It had "a sala, three rooms, and a patio, with its kitchen garden at the rear." Beginning with "an arquebus, a sword hilt, and a dagger," item by item they proceeded to list all of don Francisco's personal effects—his weapons, horse gear, his complete set of tools for making gun stocks, his household furnishings, clothing, and papers. Among the latter were titles to the Gómez encomiendas: All of the pueblo of Pecos, except for twenty-four houses held by Pedro Lucero de Godoy There were in addition estancia grants, not only for San Nicolás de las Barrancas but also for a piece of land one league above San Juan pueblo and another on the Arroyo de Tesuque. [21] After three days, they transferred Gómez to a cell at Santa Domingo next to those occupied by the other prisoners of the Holy Office. There they stagnated and sweat for five months, through the entire summer, seeing "neither sun nor moon." Meanwhile, Father Posada and Alguacil Manso embargoed their properties and sold off enough of their goods to cover the expenses of their imprisonment, their impending journey to Mexico City, and their trials. At a public auction cried June 30, July 1, and July 2 in the Santa Fe plaza, a variety of Francisco Gómez Robledo's possessions brought 325 pesos. He later charged that Governor Peñalosa rigged the bidding and through his agents knocked down whatever he wanted at a fraction of its value. When Manso had trouble rounding up and separating out don Francisco's stock on the estancia of Las Barrancas, he attached it all with a warning to the other Gómez brothers that they not remove a single head on pain of excommunication and a five-hundred peso fine. The same penalty applied to unauthorized persons collecting the revenue from the prisoners' encomiendas. [22] Posada and Peñalosa Quarrel Up to the time the Holy Office made its sudden arrests, New Mexico had seemed big enough for both Custos Posada and Governor Peñalosa. They had even cooperated. In November 1661, for instance, Peñalosa had reaffirmed the exemption from tribute of ten Indians per mission to assist the friars. But when the prelate, officiating as agent of the Inquisition, began ordering alcaldes mayores to impound encomienda revenues, the governor got his back up. Without mincing words, he challenged the Franciscan's jurisdiction over encomiendas, which were royal grants, and admonished him for giving orders to alcaldes. Posada responded that his instructions from the Holy Office were to embargo all property belonging to the prisoners, and encomienda tribute was plainly property. From the summer of 1662 until their showdown at Pecos fourteen months later, relations between governor and prelate degenerated notably. Francisco Gómez Robledo and Diego Romero were encomederos. Cristóbal de Anaya Almazán, as the eldest son in his family, became one soon after his arrest when his father died. By viceregal decree, the number of encomenderos in New Mexico had been limited to thirty-five. These men were the backbone of the colony's defense. In turn for the privilege of collecting the tribute from specified pueblos—customarily twice a year in May and October—they maintained horses and weapons and responded to the governor's call to arms. When a woman or a minor inherited encomiendas, an escudero, literally a shield bearer or squire, was appointed as a substitute to render the military service for a share of the tribute. Governor Peñalosa was quite right in insisting on escuderos to serve in lieu of the arrested encomenderos. But the way he handled the matter left little doubt that personal advantage, not defense, was uppermost in his mind. [23] When they met on the street leading to the governor's palace, Father Posada asked Peñalosa just what he intended to do. Don Diego replied that since Posada had collected the tributes in full for May 1662, without waiting for him to name escuderos, the governor should collect and hold in trust for the escuderos the full proceeds in October. After that, from May 1663 until Mexico City resolved the issue, the revenues should be divided evenly, half for the Holy Office and half to pay the escuderos. When the friar pointed out that he had ordered the May 1662 tribute collected in full because the prisoners had already earned it, Peñalosa turned a deaf ear. Worse, he set up two of his retainers as dummy escuderos so that he could pocket their share of the tribute. In the case of Francisco Gómez Robledo, he passed over four able-bodied brothers to pick Martín Carranza, described by Gómez as "a boy about twelve or fourteen years old whom he [Peñalosa] brought with him, a criollo from Pátzcuaro." [24] The Pecos Encomienda Pecos was the richest encomienda in New Mexico, even after a couple of generations of marked population decline. Gómez Robledo reckoned the revenue at 170 units per collection, or 340 per year, "in buckskins, mantas, buffalo hides, and light and heavy buffalo or elkskins." The number of units, or piezas, was equivalent to the number of indios tributarios, that is, heads of household, a figure the encomendero was doubtless slow to adjust in relation to population decrease. If the twenty-four households of Pedro Lucero de Godoy and the ten households of mission helpers exempt from tribute were added, the total for the pueblo came to 374. Using an average of three persons per household on the low side and four on the high side, a rough estimate of Pecos' population in 1662 fell between 1,122 and 1,496. Compared to his 340 units from Pecos annually, Gómez received 110 from his share of Taos, 80 from half of Shongopovi, 50 from half of Ácoma, and 30 from half of Abó. [25] Despite the imprisonment of their encomendero and the legal tangle that ensued, someone always came round to collect from the Pecos. For May 1662, Father Posada acknowledged receipt of: "one hundred sixty-eight units in poor buffalo hides, light buffalo or elkskins good only for sacks, heavy buffalo or elkskins, seventy-two buckskins large and small, and some cotton and wool mantas, all of which was valued at one hundred and fifty pesos" [26]

In October 1662, by Governor Peñalosa's order, Alcalde mayor Jerónimo de Carvajal, evidently accompanied by Lt. Gov. Pedro Manso de Valdés and Antonio González Bernal, directed the Pecos "captains" to gather in the entire fall tribute and lay it before him. Carvajal then delivered the bundles in person to the governor in Santa Fe, testifying later that Peñalosa kept everything for himself. This collection amounted to: "nineteen cotton mantas, forty-four assorted pieces [of skins], sixty-six buckskins, twenty-one white buffalo or elk skins, eighteen buffalo hides, sixteen heavy buffalo or elkskins." The Pecos captains also collected what was due from the twenty-four households of Pedro Lucero de Godoy and took it to him at his home. Again in April 1663, Carvajal returned to Pecos at Peñalosa's bidding, this time to take up half the May tribute: "twenty-nine large buckskins, forty-two assorted pieces of buckskins, eighteen buffalo hides, sixteen heavy buffalo or elkskins." seven heavy buffalo or elkskins." When he turned it over in Santa Fe, the governor forced him, said Carvajal, to alter his statement to read twenty-nine heavy buffalo or elkskins instead of large buckskins. Peñalosa then kept the buckskins, the statement, and all the rest of the delivery. The other half of the May 1663 tribute Pedro Lucero de Godoy, as receiver of his brother-in-law's income, collected on instructions from Father Posada: "thirteen buffalo hides, twenty-two light white buffalo or elkskins, eighteen heavy buffalo or elkskins, thirty buckskins good and bad but most of them good, which in all makes eighty-three units." [27] It did not seem to worry Diego de Peñalosa that he was twisting the tail of the Inquisition every time his men brought in another load of goods from an embargoed encomienda. The fact was he rather enjoyed it. "And the comisario of this Holy Office," declared a concerned Francisco Gómez Robledo, "seems not to have prevented it, for in such remote places [as New Mexico] there is no justice other than the will of the governor." [28] López Found Guilty In the case of ex-governor López de Mendizábal, still under guard in August 1662, nothing could have been further from the truth. In rapid succession, the long arms of the audiencia and the Holy Office reached out to chastise him. Found guilty by the audiencia, or high court of Mexico, on sixteen of the thirty-three charges brought against him during his residencia, López was ordered to pay 3,500 pesos in fines, plus costs, and to settle his debts with friars, colonists, and Indians. Governor Peñalosa stood to profit handsomely. However, at ten o'clock on the night of August 26, Father Posada and Alguacil Manso arrested López. Two hours later, they took into custody his literate, Italian-born, Spanish-Irish wife. All their possessions were attached. Again the Holy Office had foiled the wily Peñalosa. When it formed up in early October that year, the southbound supply train carried six unwilling passengers. Like his erstwhile aides, the distraught ex-governor López rode fettered in a wagon, doña Teresa, his wife, in a carriage behind. Careful provisions had been made for the security and safe delivery of each prisoner. At Santo Domingo on October 5, for example, Father Posada had turned over Francisco Gómez Robledo to Ensign Pedro de Arteaga who, for one hundred and fifty pesos, guaranteed to see the prisoner behind bars in Mexico City. Arteaga swore to conduct Gómez in shackles "not allowing him the least communication, nor that he be given letter, ink, or paper, nor that said prisoner be permitted to leave his wagon." Should he fail to carry out his commission, Ensign Arteaga obligated himself to pay back double his salary and suffer whatever other penalties the Inquisition might impose.

The costs for guard, shackles, food, and incidentals, were born by the prisoner and paid for out of the sale of his possessions. In addition, the Holy Office required three hundred pesos in security to cover prison expenses in Mexico City. In the wagon with Gómez rode two bales wrapped in buffalo or elkskins, worth two pesos each, containing three hundred buckskins valued at one peso a piece, along with a single trunk of his clothing. The dismal journey lasted from fall through winter to spring. Finally, in April 1663, the head jailer at the secret prison of the Holy Office checked in one Francisco Gómez Robledo of New Mexico. Ensign Arteaga had earned his pay. [29] Gómez Robledo Tried and Acquitted Gómez Robledo fared better before the inquisitors than any of the others. Even though the case against him included the ominous accusation of Judaism, it proved to be based mainly on hearsay. Bodily examination by physicians showed that don Francisco had no "little tail," as one of his brothers was alleged to have, nor could the scars on his penis be positively identified as an attempt at circumcision. In audience after audience, answering forcefully and directly, and utilizing to the best advantage the long and loyal Christian service of his father, Gómez Robledo earned himself a verdict of unqualified acquittal. [30]

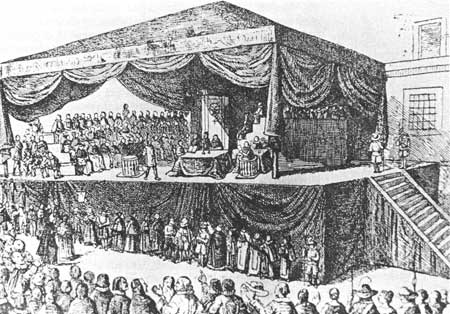

From the pounding on his door that early morning of May 4, 1662, until September 17, 1665, when again in Santa Fe he signed a release of all claims against Father Posada and Pedro Lucero de Godoy, "content and satisfied entirely and fully," the ordeal had cost Francisco Gómez Robledo three years, four months, and fourteen days of his life. In assets, it had cost him several thousand pesos. He got back his personal belongings that had not been sold, his house on the plaza, his titles to lands and encomiendas, as well as an accumulated 875 units of tribute. As for the value of tribute usurped by Governor Peñalosa, 831 pesos, Gómez judiciously requested that the sum be collected by the Holy Office and applied to its chapel in Mexico City. Not that it mattered to them, but in the fall of 1665, the Pecos Indians once again paid their tribute to don Francisco. [31] The Fate of the Others The long-suffering Bernardo López de Mendizábal died in the Inquisition jail before a verdict was reached. The case against doña Teresa was dropped. Ex-alcalde mayor Nicolás de Aguilar, found guilty, had to appear in auto de fe, the public procession of Inquisition prisoners in penitential garb, and to abjure his errors before the tribunal. He was forbidden for life to hold public office and banished from New Mexico for ten years. Cristóbal de Anaya Almazán abjured his errors before the inquisitors and was released. As a condition of his sentence, they ordered don Cristóbal, once he returned to New Mexico, to stand up during Mass on a feast day and publicly recant his false doctrine. [32] Diego Romero, who appeared as a condemned apostate and heretic in the same auto de fe with Aguilar, made a pathetic showing during his trial. At first he had tried to bluff. Gradually he broke down, implicating his fellow prisoners and admitting what a crude, ignorant, low-life person he was. Accused of incest with Juana Romero, allegedly his cousin and the mother of his son, Romero swore that she was no relative at all, but rather "a native of Pecos, of whose issue he does not know, and that his mother raised her from infancy as a mestiza." Later, Juana had fallen in with accused madam Catalina Bernal and, according to Romero, had slept with the Father Guardian of the Santa Fe convento. The blond son born to Juana was not Romero's but the friar's, as the resemblance of father and son would prove. [33]

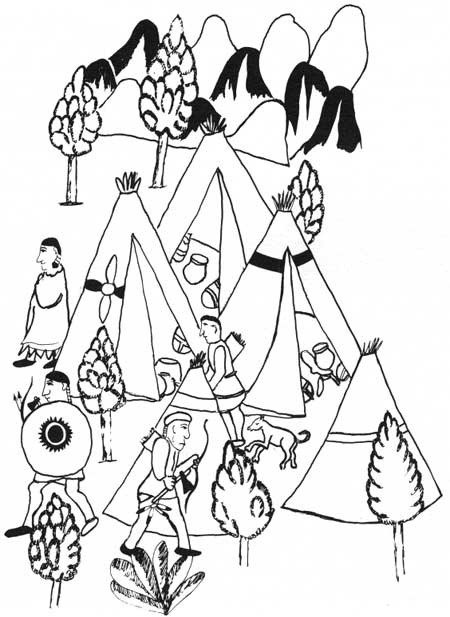

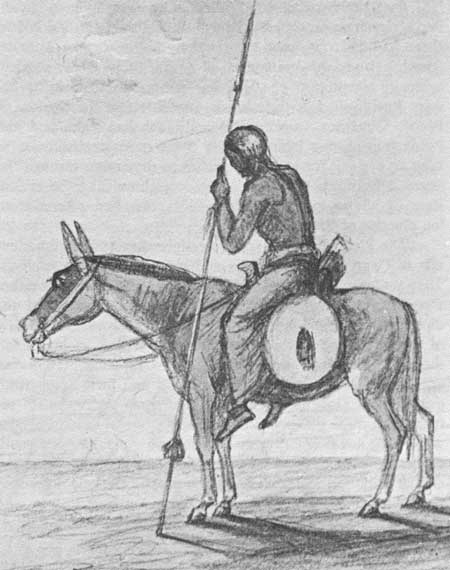

Diego Romero Feted by the Plains Apaches Certain of the other charges against Diego Romero stemmed from a trading excursion he had led to the plains at the behest of Governor López de Mendizábal. One of Romero's motives, which he admitted during his trial, was to have the Apaches install him "as their captain, as they had done with Capt. Antonio [Alonso] Baca, Francisco Luján, and Gaspar Pérez, father of the one who confesses, and with a religious of the Order of St. Francis named Fray Andrés Juárez." [34] Some Pecos Indians joined Romero. Their leader, called El Carpintero, but obviously a trader and diplomat as well, seems to have been a sort of seventeenth-century Bigotes. Back in the summer of 1660, at the head of a half-dozen Hispanos, their servants, the Pecos contingent, and a pack string of supplies and trade knives, Diego Romero rode tall in the saddle. A large, heavy-set man with curly black hair, he looked forward to cementing trade relations with the Plains Apaches. He would earn the gratitude of Governor López, have some fun, and turn a profit to boot. "Some two hundred leagues" east of the custody of New Mexico, on the "Río Colorado," the traders made camp near the Apache "rancheria or pueblo of don Pedro." Here the heathens feted Romero and El Carpintero with such gusto that the Inquisition knew about it almost before they reached home. One afternoon a group of about thirty Apaches appeared at the Spaniards' camp and formed a circle around Romero. They wanted to make him their "capitán grande de toda la Nación apache," their chief captain of the entire Apache nation. Four of the heathens left the circle, picked up Romero, and laid him face down on a new buffalo hide spread on the ground. They did the same to El Carpintero. Then they hoisted them shoulder high and began carrying them on the hides in procession "with singing and the sound of reed whistles and flutes, performing their rites." Arriving at their rancheria, the Apache bearers sat the honored guests on piles of skins in the midst of a circle of two or three hundred Indians. There followed more singing and dancing, during which natives stood on either side of the two men "shaking them." The celebration went on all through the night. There were orations, a mock battle, the smoking of a peace pipe, and, according to Romero's accusers, a heathen marriage rite.

The Spaniard had reminded his hosts that his father Gaspar Pérez—whose surname, he later told the inquisitors, he had not taken because of don Gaspar's unchristian behavior—had "left a son" among them. He too should have the honor. Accordingly, a new tipi was set up and a maiden brought. Inside on a bed of skins Romero deflowered her. Afterwards the heathens daubed his chest—some said his face and beard—with the girl's blood. They presented him with the tipi and the skins as gifts. They tied a white feather on his head. From then on, said an eyewitness, "he always wore that feather stuck in his hatband." And he swaggered. Had he not swaggered so much and had the zealous Fray Alonso de Posada not been building his case against the López regime, Romero's feat on the plains might have been told and retold only around campfires. But because it reached the halls of the Holy Office, it was set down and preserved. Here, thanks to that tribunal, is documentary evidence that by 1660 the Spaniards of New Mexico had been using "the French system" for a couple of generations to bind trade connections with Plains Indians. The participation of El Carpintero confirms the continuing role of the Pecos in this trade. Romero, denying that he ever was "married" on the plains, did admit trading a knife for sex on two occasions at another rancheria where the party stayed nine days. He called this place "la rancheria de la Porciúncula," an intriguing link to Pecos, and perhaps to the seminal ministry of Fray Andrés Juárez. [35] Romero, by throwing his miserable self on the mercy of the inquisitors, had his harsh sentence of service in the Philippine galleys commuted to banishment from New Mexico. But he had not learned his lesson. Several years later in Guanajuato, under the name Diego Pérez de Salazar, he married a mestiza. The trouble was, he already had a legal wife residing in New Mexico. Before he knew it, he was back in Mexico City, back in the stinking cárceles secretas, accused of polygamy. This time, the inquisitors were harsh with Romero. In addition to his appearance in a public auto de fe, "with insignia of a man twice married, conical hat on his head, rope around his neck, and wax candle in his hands," they sentenced him to two hundred lashes, administered as he was paraded through the streets with a crier, and to six years' labor as a galley slave. On October 23, 1678, poor Diego Romero died of "natural causes" in the public jail at Veracruz still waiting for his first galley. [36] El Carpintero, the "Christian" Pecos Indian, was of course exempt from prosecution by the Inquisition. If, as Franciscan prelate, Father Posada moved to discipline him for his part in the plains episode; the record has not come to light. Custos Posada Moves to Pecos The aggressive Alonso de Posada was still in his mid-thirties. Born to Licenciado Alonso de Llanos y Posada and María González in 1626, he hailed from western León, from the villa of Congosto, which translates "narrow pass, or canyon." Not a particularly important place, the cluster of mostly two-storied stone houses roofed with slate or tile occupied an elevated plain high above the Río Sil. "The land is of good quality," according to a nineteenth-century description, "in the main unirrigated for the Sil waters almost none of it because of the depth of the riverbed." As well as wheat, rye, various fruits, and vegetables, the people grew potatoes in abundance. There were trout and fresh-water eels in the river, which has since been dammed in the vicinity of Congosto. From there it flows south and westward toward the sea, commingling with the Río Miño to form a piece of Portugal's northern border.

On the American side of the Atlantic, the twenty-year-old Alonso had taken the habit of the Franciscans at the Convento Grande, on Saturday, October 20, 1646, at the traditional hour of compline with the entire community present. As a young missionary in New Mexico, he had seen duty at two hardship posts, at the Hopi pueblo of Awatovi between 1653 and 1655, and at Jémez in 1656. Then Fray Alonso returned to Mexico City, where his superiors soon named him custos of New Mexico and sent him back to do battle with Bernardo López de Mendizábal. That he had done with dispatch. [37] Sometime early in 1663, Father Posada moved out to Pecos, evidently to avoid bumping into Governor Peñalosa. The two men were no longer speaking. Since Christmas Day 1662, when Peñalosa had learned that his hurried shipment of goods purloined from the estate of ex-governor López had been impounded at Parral on orders from Posada, his fury had badly affected his judgment. He derided the Holy Office and composed rude doggerel about inquisitors. On one occasion he was heard to say in a rage that "if the Inquisitors opposed him the way Posada opposed him, he would scour all their assholes." He had made vile threats against Father Posada. And he never missed an opportunity to proclaim his authority as royal governor over any creature in a Franciscan habit The showdown began in August 1663. During a dispute over livestock, Peñalosa ordered the arrest of Pedro Durán y Chávez. At Santo Domingo, the prisoner escaped to the church where he invoked the right of asylum. That did not stop Peñalosa. He had Durán y Chávez dragged from the church and jailed in the governor's palace. It was an act Father Posada could not ignore. When a polite letter requesting Durán's return met with a firm refusal, the prelate rode over to Santo Domingo. To a second request, Peñalosa made no reply at all. With that, the Franciscan started legal proceedings. On September 27, he issued a formal ecclesiastical monition directing the governor to give up the prisoner within twenty-four hours or suffer excommunication. He dispatched a friar to Santa Fe with instructions to make two personal appeals, and, if they did not move Peñalosa, to serve the notice. Fray Alonso then went back to Pecos. Peñalosa Decides on Arrest The governor did not bend. Instead, he resolved to make good an earlier threat. He would arrest and deport the arrogant Franciscan. Securing the assent of Lt. Gov. Pedro Manso de Valdés and Fray Nicolás de Freitas, Peñalosa hastily set a dangerous course. It was Sunday, September 30, 1663. A moment of high drama in the long struggle of church and state in New Mexico was about to take place in the convento at Pecos between two strong, unflinching individuals. [38] Without fanfare, the governor issued a call to arms to a select group of encomenderos. According to a statement by five of them who later sought absolution from Father Posada, "All of us were utterly unprepared, not at all willing, some reaping our wheat, others winnowing theirs, when Gen. Diego de Peñalosa summoned us one at a time without any of us knowing of the others." Each was to mount up, bring his arquebus, and await the governor at a place a quarter-league out of Santa Fe. There they came together. About three in the afternoon Peñalosa rode up. He asked them, "Which way to Pecos?" Told that the road lay before him, he spurred his horse and ordered them to follow. Before long, don Diego called to Capt. Diego Lucero de Godoy, who rode a fine horse, to go on ahead and ask the native governor "in all secrecy how many friars there are at the pueblo of Pecos and if the Father Custos is there. If by chance you run into him on the road shout to him that something just occurred to you and return in all haste to report to me." Lucero did as ordered. The Pecos governor told him that only Father Posada and Father Juan de la Chica were there. Riding back at a gallop, Lucero missed the main party, which "had taken another trail to the pueblo," but he doubled back to join them as they dismounted under some cottonwoods within sight of the convento. There were ten or twelve of them. "All proceeded on foot," said the five in their statement,

It was sometime between nine and ten at night. Peñalosa posted a guard outside the main door with orders to kill anyone who tried to come out. Some witnesses remembered him saying, "Should St. Francis come out, kill him!" Then the governor and his armed men went inside. Father Posada recalled their unexpected arrival in these words:

The Franciscan noted that Peñalosa had a pair of horse pistols in his belt. Lieutenant Governor Manso de Valdés entered with arquebus in hand, "apparently with hammer cocked." Obeying an impulse, Francisco de Madrid set his weapon aside. Lucero de Godoy released his hammer. Diego González Lobón came in holding a pistol. Later, before the Inquisition, don Diego de Peñalosa denied that he and his men were any more heavily armed than usual. Confrontation of Governor and Custos The most complete account of what happened next is from the pen of Father Posada. Although Peñalosa disputed certain of the details, he did admit before the tribunal of the Holy Office that "he was so impassioned and so blind that without considering more than the harm done to him he resolved to exile said Father Custos from the provinces of New Mexico." [41] The friar asked the governor what he was doing in the vicinity of Pecos at that hour. "We have come for a refugee," Peñalosa retorted with calculated irony, "and therefore, Your Reverence, you must throw open the doors for us in the name of the king." The Franciscan did.

Back in the guest cell, Peñalosa pressed Posada. He must go to Santa Fe at once, that very night. When the friar explained that it was not his custom to go out at night, and offered instead to give his guests supper and a place to sleep, the governor invited the prelate to step out into the cloister.

When the shouting ceased, according to the guards, who had indeed heard the governor saying "many vituperative things," the two men went back inside. Father Posada began taking out books to inform Peñalosa of the immunities a clergy man enjoyed as Franciscan prelate, ecclesiastical judge ordinary, and agent of the Holy Office. The governor was not impressed. He told the friar to save his breath. Anyone could see that the priest "was the student of a book and that he himself was a clod." Still, said Peñalosa, he knew more than Posada. Posada Taken from Pecos A third time the governor told the prelate that he was required in Santa Fe at once. Still protesting the hour, Posada ordered an animal saddled. He wanted to know if he was being taken as a prisoner. Peñalosa said no, he was merely going to honor the governor's palace with his presence. "I shall do so to comply with your command," vowed the grim-faced Franciscan, "but I give notice that I am not going freely." He would force the governor's hand.

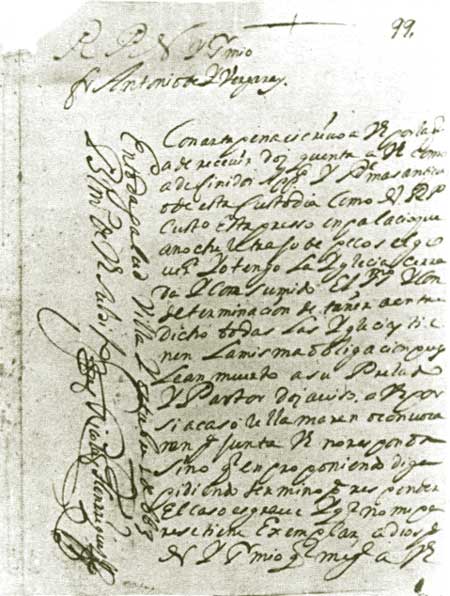

No sooner had they begun the long night's ride when Peñalosa leaned over and said something about the embargo Posada had placed on the goods in Parral. From the tone of the conversation the prelate thought he could feel the governor's mortal hatred. A little less than a league down the trail, "before leaving the milpas of the pueblo of Pecos," he asked again if he was Peñalosa's prisoner. The governor lied. He told the Franciscan that once they reached Santa Fe, he would leave him at the convento. The rest of the way in, recalled the soldiers, "they came chatting on the trail most sociably." In Santa Fe, the sarcastic Peñalosa insisted that Posada join him at the governor's palace for chocolate. As they came opposite the gallows that had been erected in the center of the plaza "to hang an Indian" said Peñalosa, certain threatening remarks were made. The prelate then disappeared into the casas reales. [42] The Custos a Prisoner About 6:00 a.m. Monday morning, October 1, the Franciscans at the convento in Santa Fe learned what had happened. They were stunned. They had grown used to don Diego's blasphemous threats, but now he had actually done it—locked up the Father Custos. Fray Nicolás de Enríquez, guardian of the convento, reacted swiftly, closing the Santa Fe church and ordering the host consumed. He considered placing all the churches of New Mexico under interdict. "With the utmost anxiety" he penned a hasty note to Fray Antonio de Ibargaray at Galisteo, "definitor and senior Father of this custody," telling him of the prelate's arrest and warning him to be on his guard. "The situation is grave," he concluded, "and to my knowledge without precedent." [43] Ibargaray had the note by three that afternoon. It only confirmed what he had learned by twenty-nine years' experience in New Mexico—that the governors proceeded, in his words, "as absolute lords, that there is no law other than what they desire, and that not even the immunity of churches is sacred." He knew how to handle the likes of Diego de Peñalosa. Ex-governor López de Mendizábal had characterized Father Ibargaray as "very headstrong and uncontrolled. When Gen. don Juan de Samaniego was governor [1653-1656, while Ibaragaray was custos], this friar seized him and threatened him, telling him that he had trampled the church under foot when he punished the heathen enemy without consulting the religious." But Ibargaray was not as young now, nor was he the prelate. This time he sat down and wrote the Inquisition, urging the tribunal to act "with the utmost dispatch to defend your minister and agent." [44]

For nine days the colony held its breath. The two light field pieces which the governor ordered positioned to prevent the prelate's escape testified to the gravity of the situation. At many of the missions, the friars followed Father Enríquez' lead, locking the churches. They even refrained from celebrating Mass on the feast day of St. Francis, October 4. How Fray Juan de la Chica, who evidently remained at Pecos, answered the questions of the Indians, we can only guess. Surely he made Governor Peñalosa out another Attila. [45] Meanwhile, inside the governor's palace, Peñalosa and Posada kept up a running argument over their respective authority. Mediators came and went. The governor wanted to expel the prelate for overstepping his ecclesiastical jurisdiction and for sedition. When it became clear to him that he could not build up a strong enough case, he looked for a way out. Father Posada, "in order to avoid greater evils," directed the friars to reopen the Santa Fe church and admit Peñalosa to the sacraments. Although it went against his grain, the dauntless Franciscan finally agreed to drop the whole matter, "insofar as possible," in exchange for an end to the impasse. The governor released him the same day. The ordeal was over. Posada Builds His Case Father Ibargaray's appeal for help did not reach the Holy Office, until early February 1664. In early March, don Diego de Peñalosa made his exit. He knew the inquisitor's file on him was growing, and he had no intention of allowing Father Posada the satisfaction of arresting him as he had arrested his predecessor. Once the governor was gone, Posada set aside the agreement he had accepted under duress and prosecuted the case with vigor. He had no trouble finding witnesses. [46] Most of the testimony related in one way or another to Governor Peñalosa's obstruction of Holy Office business and his utter disrespect for the tribunal's authority. He had ignored Inquisition embargoes, appropriating the goods of former governor López and collecting the ecomienda revenues of the arrested New Mexicans. He had seized, opened, and read Inquisition mail. He had terrorized Agent Posada in an effort to force him to release the goods impounded in Parral, even to bodily removing him from Pecos and imprisoning him in Santa Fe. He had made a mockery of ecclesiastical immunity and the right of asylum. Less weighty in the eyes of the inquisitors, but indicative nonetheless, were the accounts of Peñalosa's devil-may-care lack of moral propriety. He had delighted in flaunting the young mistress he picked up en route to New Mexico. He had sported also with local females. His language was the filthiest, his jokes the most obscene. With undisguised glee, he often made the friars the butt of his crude humor. Testifying before Father Posada at the estancia of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios de los Cerrillos, the alluring doña Margarita Márquez, wife of Alcalde mayor Jerónimo de Carvajal and former mistress of Governor Manso, now in her mid-twenties, offered some examples. Asked if she had ever heard anyone say that the woman who got pregnant by a governor had her womb consecrated, doña Margarita responded with a variation on the same theme. Don Diego de Peñalosa on his way to New Spain had stopped over to say good-by at the Cerrillos estancia. He had summoned her to his room. Knowing of don Diego's appetites, she had asked her mother to go with her. There, before Margarita, her mother, and another woman, the governor spoke in this low vein, if we can believe the testimony.

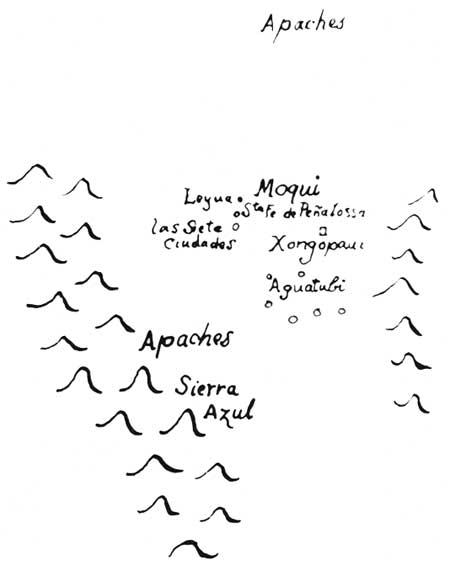

The virile Franciscan may have blushed. Although his varied duties as agent of the Inquisition, even to seeking out such testimony as doña Margarita's, as ecclesiastical judge, and as prelate kept him moving about, Father Posada evidently continued to serve as guardian at Pecos. It was to the Pecos convento that the released but unrepentant Cristóbal de Anaya Almazán reported in June 1665. He thrust at the friar an order from the Holy Office releasing his property. He did not present notice of the Inquisition's sentence, as he had been instructed to do, but rather went around boasting that his good name had been wholly restored and that the persons who had testified against him were soon to be arrested. A month later, Posada called his bluff. Not really contrite, Anaya stood at the main altar in the Sandía church during the offertory. It was Sunday morning. He was about to confess before Father Posada and the entire congregation the error of his false doctrine. He had been wrong, he told them, to deny the spiritual relationship of baptizer, baptized, parents, and godparents. Outside afterwards he was as cocky as ever. [48] Peñalosa Tried by the Inquisition In Mexico City meantime, the Inquisition had arrested don Diego de Peñalosa. Formal accusation of the reckless ex-governor ran to 237 articles and took two days to read. When the final sentence was handed down twenty months later, it was harsh—appearance in a public auto de fe, a fine, lifelong exclusion from civil or military office, and perpetual banishment from New Spain and the West Indies. That would have broken most men. Not don Diego. As the self-proclaimed Count of Santa Fe, the cavalier Peñalosa would reappear first in Restoration England and then at the teeming court of Louis XIV. He offered blueprints for an invasion of mineral-rich Spanish America. His intrigues in fact helped launch the famed Sieur de la Salle for the last time. In 1687, the year La Salle perished violently at the hands of his own men in the wilds of Texas, don Diego died in France. His zestful career, from Peru to Pecos to Paris, had finally closed. [49] Fray Alonso de Posada, the Franciscan champion who had brought low two of New Mexico's high-and-mighty roguish governors, left the colony with the returning supply wagons in the fall of 1665. Years later he was called upon by the viceroy to report on the lands and peoples east from New Mexico. The Spaniards had heard of Peñalosa's intrigues at the French court. Reliable sources indicated that "the count" had presented to King Louis a plan to capture the provinces of Quivira and Teguayo "assuring him that they are very rich in silver and gold." News that La Salle had sailed added urgency to such reports. Responding in 1686, Father Posada drew in part on his experience at Pecos. Speaking of the Plains Apaches, he wrote:

A Satire of New Mexico After Posada, no friar ever wielded the authority of the Inquisition in New Mexico the way he had. Fray Juan de Paz, his successor in 1665 as both agent and custos, evidently wanted to. Instead, he stirred up such a storm of local resentment that the Holy Office was obliged to reevaluate its role in the colony. Father Paz, it appeared, wanted "to make every affair and case an Inquisition matter," not merely to insure the purity of the Faith but also to intimidate opponents of the friars' regime. If the Franciscans were using the authority of the Holy Office to maintain their privileged ecclesiastical monopoly in New Mexico, that was patently wrong. Having admonished Paz to keep peace with the civil authorities, the inquisitors listened with concern to the complaints that reached them late in 1667. [51] "We beg you," wrote the Santa Fe cabildo, "to free us of such duress, so many troubles and miseries as we poor soldiers suffer at the hands of these religious." Ever since its founding seventy years before, vast and remote New Mexico had groaned, the municipal council said, under the oppression of litigious Franciscans. The friars were the only ecclesiastical law. They were the judges. They heard and recorded all testimony. Because there were no lawyers in the colony to offer counsel, the citizen stood defenseless and fearful before the arbitrary justice of the Franciscans. For no greater offense than hiring an Indian laborer against the will of a friar, New Mexicans were threatened with prosecution by the Inquisition. Such intimidation was commonplace. What moved the cabildo to appeal at this juncture was not so common. The Friars Reprimanded by Holy Office Fray Nicolás de Enríquez, appointed notary of the Inquisition by Father Paz, had written a scurrilous satire "against this entire kingdom, stripping everyone in it of his dignity, from the governor to this cabildo." The populace clamored for the cabildo to do something. Cristóbal de Chávez went after Fray Nicolás with his dagger, and the friar had to run for his life. To prevent another such scene, the cabildo had petitioned Custos Paz to punish Enríquez and send him back to Mexico City. Instead the prelate embraced this friar and appeared with him in the streets. Worse, under pain of ecclesiastical censure, Paz tried to suppress the case by seizing the pertinent papers, including the cabildo's file copy of the satire, a bootless move since many persons already knew the words by heart. To avoid more litigation with the custos, the cabildo laid the matter before the Holy Office, enclosing a copy of the repugnant satire. The cabildo also made a significant recommendation—that the Holy Office appoint as its local agent a secular clergy man, not a friar. The tithe and the revenue from the confraternity of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios were sufficient to support him. They had already petitioned the bishop of Durango to appoint a secular vicar as ecclesiastical judge ordinary. Although the Franciscan commissary general successfully quashed these attempts to break the Order's monopoly of ecclesiastical justice in New Mexico, they did serve as a warning to overzealous friars. [52] In the matter of the satire, the attorney of the Holy Office sustained the cabildo. He advised that the inquisitors instruct Agent Paz not to employ Fray Nicolás de Enríquez in any Inquisition business whatever. In addition, a secret investigation should be made to determine if he really was the author, and the cabildo should be assured that any official of the Inquisition guilty of wrongdoing would be punished. [53] If he was the author, as everyone in New Mexico seemed to think, Enríquez may have penned his controversial satire at Pecos. A native of Zacatecas in his mid-forties, he had probably arrived in New Mexico with Father Posada in 1661. He had been guardian of the Santa Fe convento during the worst of the Peñalosa-Posada feud. After Posada left the colony in 1665, one Fray Nicolás de Echevarría, from the mining town of Sierra de Pinos southeast of Zacatecas, took over as guardian at Pecos. He did not last. [54] By late 1666, when called by Agent Paz to testify against Cristóbal de Anaya Almazán, Fray Nicolás de Enríquez had moved in at Pecos. He did not last either. By July 1667, three months before the cabildo sent a copy of the satire to the Holy Office, Nicolás de Enríquez testified as guardian of Zia. Just to confuse the succession, it would seem, another Enríquez, aged Fray Diego, a Spaniard who had affiliated himself with the Mexican province in 1626 and evidently no relative, took his place at Pecos. About the same time Fray Juan de Talabán succeeded Father Paz as custos. The latter continued for another year as agent of the Holy Office. The death of Fray Nicolás de Enríquez, probably in 1668, cheated the cabildo of seeing the friar who had allegedly ridiculed an entire colony receive his just deserts. [55] The colonists rejoiced at the fall of Fray Juan de Paz. Last of the Franciscans in New Mexico to serve simultaneously as custos and as agent of the Holy Office, he had failed to grasp the inquisitors' growing desire to disassociate the authority of the Inquisition and local politics. When they reviewed his proceedings in Mexico City, they decided that impropriety, gross ignorance, and inattention to the obligations of the office had characterized his tenure. They threw out the cases he submitted. Commenting on his evidence against Juan Domínguez de Mendoza, the inquisitors noted, "All the witnesses who testify against him are friars and it appears that they are inspired by malice." [56] Agent Bernal at Pecos Just arrived from Mexico City, the cautious new agent, Fray Juan Bernal, probably on the advice of Alonso de Posada, chose as his headquarters the prudently out-of-the-way convento of Pecos. There on January 19, 1669, he swore in as notary Fray Francisco Gómez de la Cadena. The previous notary, appointed by Father Paz in the wake of the Enríquez scandal, was impeded by illness, said Bernal, "and many leagues from this convento of Pecos." Two days later ex-agent Paz signed a hastily compiled inventory of Inquisition papers, formally surrendering them to his successor. They included correspondence, edicts of the Faith, instructions from the inquisitors, and a whole array of confidential cases that Bernal would soon discover were in a horrible mess. [57] The son of Bartolomé Bernal, native of San Lúcar de Barrameda on the Andalusian coast, and Beatriz de la Barrera of Sevilla, Juan had been born a criollo in the City of Mexico. On February 12, 1648, at the Convento Grande, he put on the robe of St. Francis. He was only fifteen years and four months old. Twenty years a friar, Bernal was still in his mid-thirties in 1669. As he and his notary worked to bring order out of the jumble left by Paz, which entailed among other things chasing down witnesses who after two and three years still had not ratified their declarations, Bernal would need all the stamina he could muster. [58] Strange Case of Bernardo Gruber By spring, the new agent had pulled together enough of the loose ends of one case to submit the proceedings to Mexico City. It concerned Bernardo Gruber, a Sonora-based German peddler accused of distributing along with his wares certain mysterious little slips of paper and claiming that "whoever would chew one of these papers would make himself invulnerable for twenty-four hours." Father Paz had arrested Gruber straight-away. Since April of 1668, the poor wretch had been locked up in "one of the safest rooms" of Capt. Francisco de Ortega's hacienda in the Sandía district. For the benefit of the inquisitors, Father Bernal characterized as best he could the various witnesses in the case, one "a mulatto, but a truthful man and a good Christian," another "a mestizo and a quiet boy of good reputation and fairly reliable." He explained why it had not been possible to ship Gruber to Mexico City. In so doing, he painted a graphic picture of conditions in New Mexico, dismal at best, even when allowance is made for exaggeration. New Mexico's Dire State in 1669

If God sent rain Bernal would send Gruber. The southbound supply wagons would be leaving in November. Before then, however, he hoped to have instructions from the Holy Office. When nothing arrived until much later, Gruber stayed locked up. [59] Agent Bernal had his problems. He soon discovered how much work it was to carry on judicial proceedings in a colony so vast and so perilous. "I can neither summon anyone nor go myself to where it can be done, for everyone is afoot, without animals, because the heathen enemy have stolen them." Father Gómez de la Cadena, his notary, fell ill. On February 4, 1670, in the guardian's cell at Pecos, he swore in another one, Father Pedro de Ávila y Ayala, who was already living at the mission. Fray Pedro, a hardy, zealous sort, had traveled in 1668 from the province of Yucatan to Mexico City begging alms for the sacred places in the Holy Land. When he saw the supply train forming up for New Mexico, he was overcome, said the pious chronicler Vetancurt, by a desire to save souls. He had volunteered and ridden north with Bernal.

On the last day of February, trail-weary Brother Blas de Herrera, whom Bernal had sent to Mexico City with the Gruber case eleven months before, reappeared at Pecos with a packet of documents in response. The inquisitors expressed their disgust at the way Father Paz had proceeded against the German. They warned Bernal that local agents did not have the authority to arrest the accused in such a case without express orders from the Holy Office. In another letter, they reiterated that disrespect for the Franciscans was not an Inquisition matter. An agent must not meddle in affairs that lay beyond the jurisdiction of his office "thus giving rise to much prejudice and hatred against this Tribunal." The admonition was for Bernal's own good, "so that with due care he may avoid what his predecessor has brought about by his ignorance." Still, no one released poor Gruber. [60] The only case of record initiated by Agent Bernal was against an illiterate soldier named Francisco Tremiño, "a man who swears all day long, and is a desperate character." Several witnesses who appeared at Pecos that spring of 1670 to denounce Tremiño alleged that he was in league with the devil. One of them, Antonio de Ávalos, later described as "a native of New Mexico, of good stature, tall and slender, dark with an aquiline face and crooked nose, and coarse hair," Bernal characterized as "one of the lowliest men in these provinces." As for Tremiño, he lit out for Sonora and was apparently never brought to trial. During Lent some Apaches made off with Bernal's riding animals leaving the agent of the Holy Office "practically afoot." [61]

Gruber Escapes After twenty-seven months of confinement, Bernardo Gruber escaped. Breaking a window and pushing out one of the heavy wooden bars, he had made his getaway with the help of the Apache servant who was guarding him. Together they had fled south in the night with five horses and an arquebus. On Saturday, June 28, 1670, a distressed and out-of-breath Capt. Francisco de Ortega, who had borrowed a horse to get to Pecos, detailed the entire episode for Father Bernal. Within two days the Franciscan had notified Gov. Juan de Medrano y Mesía of the escape and of the dereliction of the local officials who refused to aid Ortega in pursuit. The governor dispatched Cristóbal de Anaya Almazán with a squad of soldiers and forty Indians. Bernal had Fray Pedro de Avila y Áyala draw up bulletins alerting the agents of the Inquisition in Parral and Sonora. He then sent his notary to inspect the scene and verify Ortega's story. It checked out. The bar had been removed. Gruber was gone. [62]

The following week, when Father Bernal wrote the Holy Office from Sandía, he was feeling very much like Job. Apaches and famine still stalked the land. He still had not straightened out and completed the farrago of Inquisition records, but with God's help he would. The trouble was, he admitted, "they are so mixed up and confused that I do not understand them." Lord knew, he was trying.

Later that summer, there was news of the fugitive Bernardo Gruber. A party of travelers making their way through the forlorn and shimmering desert stretch south of Socorro in mid-July came upon a dead horse tethered to a lonely tree. Nearby they found articles of clothing, apparently Gruber's. A further search turned up his hair, more bits of clothing, and "in very widely separated places the skull, three ribs, two long bones, and two other little bones which had been gnawed by animals."

It appeared that Gruber's Apache companion had killed him for the other horses and the arquebus. If to cover his tracks the wily Gruber had murdered the Apache, tethered the horse, and planted the clothing, no one ever suspected it. In Mexico City, the inquisitors resolved that the dead peddler's wares be sold at auction, that Mass be said for the repose of his soul, and that his bones be given a church burial. Although the life of this luckless German wanderer has long been forgotten, his death gave name to, or at least reinforced the name of the Jornada del Muerto, the Dead Man's Route. [64] Bernal Wraps Up Inquisition Business Back in his cell at Pecos, the conscientious Bernal pored over document after document in an effort to conclude every bit of Inquisition business left undone by his predecessor. There was, for example, the matter of four dozen confiscated packs of playing cards that Father Paz had turned over to Maese de campo Pedro Lucero de Godoy, local depositary of the royal treasury. He was to sell the packs at two pesos each in New Mexico commodities. During a period of two years and eight months, Lucero had sold only one pack. Not only were the cards damaged and worm-eaten from five years' storage, but the stamp on them did not correspond. Besides, anyone who wanted playing cards bought them at the store of Governor Medrano, the one store in the colony. The only way to move the cards, Bernal reckoned, was to sell them to the governor at half price "in the most respected commodity of this country, that it in standard tanned skins, being the commodity most readily sold in New Spain." The governor consented. At Pecos on November 22, 1670, his agent gave a promissory note for the forty-seven skins. Seven months later in Santa Fe, notary Ávila y Ayala certified receipt of the skins, the same day entrusting them to Lucero de Godoy who added two more for the single pack he had sold at the original price. Finally, on September 4, 1672, Father Bernal ordered Lucero to deliver the skins to Franciscan procurator Fray Felipe Montes who was about to depart with the returning supply wagons. That, to Bernal's relief, was an end to that. [65] Fray Juan Bernal, sober and unobtrusive, persevered as the Inquisition's agent in New Mexico, seemingly as late as 1679, the year his superiors in Mexico City named him custos. On the roster compiled by the New Mexico chapter in August 1672, Bernal was listed as a definitor of the custody and as guardian not at Pecos but at Galisteo, where eight years later he would suffer a violent death. [66] The Martyrdom of Ávila y Ayala at Hawikuh His former notary, the ardent Fray Pedro de Ávila y Ayala, accepted the heavier cross of Hawikuh among the Zuñis. Within months he was dead. Western Apaches, emboldened by drought and famine, swept into the pueblo in 1673 killing, burning, and looting. Father Ávila y Ayala died, according to Vetancurt, as a proper martyr should. He fled into the church and embraced a cross and an image of Our Lady. They dragged him out and stripped off his habit. At the foot of a large cross in the patio they stoned him, shot arrows at the writhing nude figure, and finally smashed his head with a heavy bell. [67]