Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Actually, neither people nor place really died. They simply parted company. At Jémez pueblo, the Pecos refugees settled into homes and planted fields provided by their hosts, but they did not forget who they were. They spoke the same language, noted Lt. James H. Simpson in 1849, but they "differ somewhat in their religious customs." They did not forget even as one generation followed upon the next. Studying Jémez in the early 1920s, anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons came away with the impression

The Jémez people had welcomed the remnant of powerful Pecos. These immigrants, headed by Juan Antonio Toya, brought with them religious objects and practices to add to those of Jémez. They brought with them the Pecos bull, and fetiches, and the Pecos Eagle Catchers' society. And they brought an image of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles, La Porciúncula, whose feast, August 2, the pueblo of Jémez began to celebrate along with that of its own patron San Diego. Not everything they carried from Pecos stayed at Jémez however. In 1882, for example, Judge L. Bradford Prince "obtained" from Pecos immigrant Agustín Cota a wooden plaque of Our Lady of the Angels from the mission church at Pecos, or so Cota led Prince to believe.

They did not forget. From time to time they made pilgrimages back to their ancestral home, where they continued to maintain shrines. Another link, forged mainly of paper by agencies of the United States government, bound the displaced Pecos and the memory of the land they had once occupied. For more than a century, from 1855, when a claim to the Pecos league was filed in behalf of "the inhabitants of Pecos Pueblo," until 1959, when the Indian Claims Commission dismissed the last Pecos bid for additional compensation, the existence of a recognizable community of Pecos Indians at Jémez vaguely disquieted those who took up the land in their absence. Not that the Pecos ever seriously thought of reoccupying their league. They were too few. Besides, Hispanos had long been farming the good land along the river. What they wanted, they explained to Superintendent of Indian Affairs Michael Steck in 1864, was permission to sell the 18,763.33 acres confirmed to them by Congress. Steck promised to ask the commissioner in Washington. The claimants, all residents of Jémez, now numbered seven men and twenty-five women and children. Because the Pecos Pueblo grant included several hundred acres of fine farm land "and one of the best water powers in the Territory," its sale, Steck though, could bring $10,000 or more. Later in 1864, the government issued a patent. Juan Antonio Toya now had a paper.

Four years hence, Toya and ten others, three of them women, put their x's on paper and their grant in the hands of indispensable, resilient, sometimes drunken John N. Ward, special agent to the Pueblos, their friend. For $10.00 they sold to Ward the northern quarter outright, that portion already encroached upon by Hispano residents of Pecos village. At the same time, they gave him power of attorney to sell the rest in their behalf. Ward cast about for a buyer. The U.S. Supreme Court, meantime, lent its support, deciding in United States v. Joseph (1876) that the Pueblo Indians were not wards of the government and therefore, like other citizens, could dispose of their property as they saw fit. By 1872, Ward had found his buyer, the debonair Las Vegas merchant and speculator Frank Chapman. The price to the Pecos for their three-quarters was $4,000, the price to Ward for his quarter, $1,300. That should have been that, as far as the Pecos were concerned, but it was not. Forty years down the road—after title to the grant had changed hands several times, at least once over a meal in a New York restaurant, after "a large hotel scheme for the ruins of Pecos" was scrapped and a fortune made cutting railroad ties, after purchase by the mercantile firm of Gross, Kelly and Company—the Supreme Court reversed itself. It found in United States v. Sandoval (1913), marvelous to relate, that the Pueblo Indians had been wards of the government after all. Therefore they could not have alienated their lands. Therefore Gross, Kelly and Company's paper title was invalid, or was it? Therefore the Hispanos of Pecos village were illegal squatters, or were they?

The outcry was resounding. Dozens of lawyers hurried into the fray, along with champions of Indian rights like John Collier and Stella Atwood. One estimate put the number of non-Indian, property-holding trespassers on Pueblo grants at three thousand. Were they all to be ejected and the lands restored to the Indians? Were they to be compensated? Or were they to stay put and let the government compensate the Indians? And what about a long-abandoned pueblo like Pecos? On the advice of white friends, Pablo Toya, son of Juan Antonio, requested in 1921 a certified copy of the patent to the Pecos Pueblo grant. The paper issued to his father had been lost. The three-man Pueblo Lands Board, created by Congress in 1924 to identify all valid non-Indian holdings within the external boundaries of recognized Pueblo Indian grants or purchases and to assess the Pueblos' losses, did not get around to Pecos until 1929. Even though, the pueblo had been abandoned under the previous sovereignty of Mexico, the Board reasoned that the United States government, by confirming the grant to the Pecos remnant at Jémez, had obligated itself to protect the Indians' interest, which it had failed to do. As a result, the Indians claiming Pecos ancestry—whose numbers based on church records were now estimated as high as 250—deserved an award.

In the meantime, Gross, Kelly and Company had filed suit to quiet title on the whole grant. Rather than do battle in the courts with the exising village of Pecos, the company gave up its claim to the northern half in return for a quitclaim to the southern 9,831 acres. That settled that. The Pueblo Lands Board found in 1930 that the 339 adverse claims to Pecos lands had legally and utterly extinguished all Indian title to the entire 18,763.33-acre grant. None of the land was recoverable. As compensation, the Board recommended $1.50 per acre, based upon "approximate average value from the occupancy of this territory in 1846 to the present time," which amounted to an award of $28,145.00. In 1931, Congress appropriated that sum to the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the Pecos remnant at Jémez. Again that should have been that.

But in 1946 the Indian Claims Commission Act, intended to settle once and for all Indian claims against the United States for loss of aboriginal lands, opened the door again. Instead of seeking to establish the Pecos Indians' shadowy claim to aboriginal territory, which, in the hands of competent expert witnesses might have been made to encompass all the drainage of the Pecos River for at least sixty miles from Tererro to Anton Chico, attorneys for the "Pueblo de Pecos" attacked only the amount of the previous award. It was, they alleged in a petition filed July 30, 1951, both "inadequate and insufficient." In response, the government alleged that the Pueblo de Pecos was not now a proper party to bring suit. The Pecos remnant and the Jémez, it seemed, had been merged in 1936 into the consolidated Pueblo de Jémez. Only it could bring suit. Undaunted, the lawyers for the Pecos in 1955 bid to amend their original petition by making the claimant all-inclusive: the "Pueblo de Pecos, Pueblo de Jémez, and Pueblo de Jémez acting for and on behalf of Pueblo de Pecos." They further moved to include "a plea of lack of fair and honorable dealings" on the part of the Pueblo Lands Board. It worked. Over government objections, the Commission allowed the a mended petition. Finally heard on its merits in 1959, the Pecos plea fell short. The Commission, after reviewing the dealings of the Pueblo Lands Board, could find no evidence of negligence or unfairness. Since neither the Pecos nor the United States had appealed the decision at the time, the initial award stood as "a final judgment fixing the value of the lands and water rights lost by the Pecos Pueblo." Such a judgment was not subject to review or revision by the Indian Claims Commission. Case dismissed. Still, they have not forgotten. Emboldened by the precedent of the Taos Blue Lake decision in 1971, which returned to the ownership of Taos pueblo an object of religious veneration, the Pecos have asked the New Mexico Department of Fish and Game to return to them the cave at Tererro, sixteen miles up the Pecos River from their former pueblo. It is sacred ground, they say. While the last of the Pecos "kept the faith" at Jémez, a motley procession of traders, soldiers, and tourists was tracking through the ruins of their former homes, scratching graffiti, pocketing souvenirs, and recounting the fantastic tales of "a lost civilization." If Thomas James heard the tales in 1821, he did not repeat them. Ten years later, Albert Pike heard them all right—Montezuma, the eternal fire in a cave, and worship of a giant snake—but he did not fix them precisely on Pecos. That came soon enough. An article by "El Doctor Masure" in the Santa Fe Republican of September 24, 1847, told of a visit in 1835 to the "furnace of Montezuma" at Pecos. Josiah Gregg, too, said that he had descended into a Pecos kiva and "beheld this consecrated fire, silently smouldering under a covering of ashes, in the basin of a small altar." Ever since the sixteenth century, Spanish chroniclers had associated ruins north of Mexico with the origin of the Aztecs and with Montezuma. The legendary pre-conquest feathered serpent had slithered northward even earlier. When, in the romantic atmosphere of the nineteenth century, Pecos became a bona fide and easily accessible ruin, it is no wonder that such specters took up residence here. "Ere the May-flower drifted to Plymouth's snowy rock, this vestal flame was burning. . . . and yet till Montezuma shall return—so ran the charge—that fire must burn."

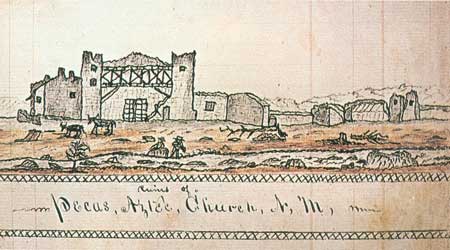

Artist John Mix Stanley, with the invading Army of the West in 1846, sketched both mission church and pueblo ruins, and in House Executive Document No. 41 of the Thirtieth Congress, First Session, the former was labeled "Catholic Church" and the latter "Astek Church." Army engineers W. H. Emory and J. W. Abert related the Montezuma legend at Pecos, where "the fires from the 'estuffa' burned and sent their incense through the same altars from which was preached the doctrine of Christ" and where "they were said to keep an immense serpent, to which they sacrificed human victims." Yet no one topped young Pvt. Josiah M. Rice, who passed by in 1851 with Col. Edwin V. Sumner's command. "There are," claimed Rice, "many traditions connected with this old church, one of which is that it was built by a race of giants, fifty feet in height. But these, dying off, they were succeeded by dwarfs, with red heads who, being in their turn exterminated, were followed by the Aztecs." Pondering Montezuma's alleged birth at Pecos and his vow to return, the astute Adolph F. Bandelier in 1880 ascribed the tale to "an evident mixture of a name with the Christian faith in a personal redeemer, and dim recollections of Coronado's presence and promise to return." Of course it may also have become a convenient ruse employed by the Pueblos to mislead inquisitive whites. Lt. John G. Bourke, contemporary of Bandelier and ethnologist in his own right, found the Montezuma story "among the Pueblos who have had most to do with Americans and Mexicans and among no others." No matter, thought historian Ralph Emerson Twitchell in 1910. "This story is the veriest rot." The big snake, in whose veracity Bandelier refused to believe "until I am compelled," persisted nonetheless. In 1924, a grandson of Maríano Ruiz, chief informant of Bandelier, recited what he had heard his grandfather tell about the Pecos snake. This account appeared in Edward S. Curtis' The North American Indians, volume 17.

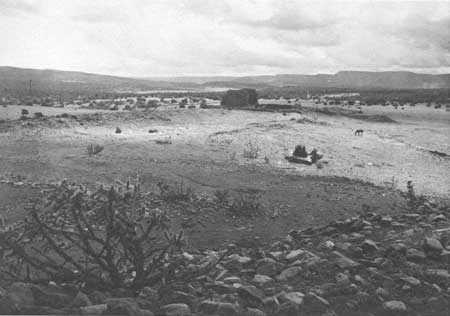

Some observers recorded more mundane theories of why the Pecos had departed. Certainly disease and warfare had figured prominently in the pueblo's decline. Santa Fe trader James Josiah Webb, passing through in 1844, surmised that the inhabitants "had become so reduced in numbers that they were unable to keep their irrigating ditches in repair, and other necessary community labor, to support themselves in comfort." Looking at it from a different angle, Indian Agent John Greiner asserted in 1852 that the Pecos had been "annoyed beyond endurance by the Mexicans living in their houses and seizing their property by piecemeal." Finally they had given up. "The pueblo of Pecos is now a mass of ruins," reported John Ward in 1867.

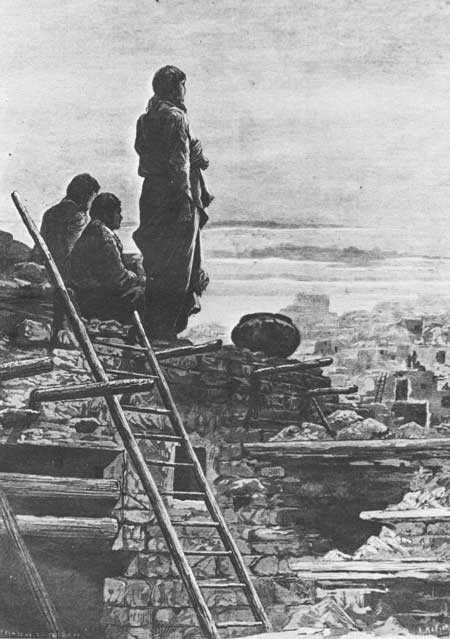

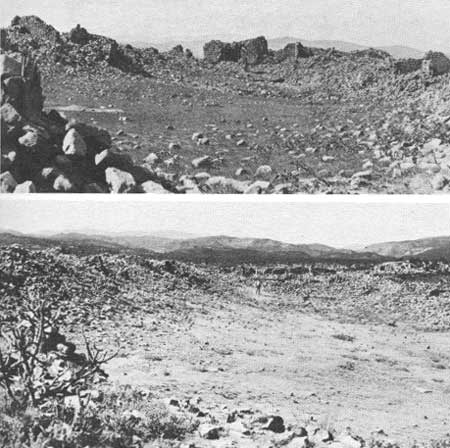

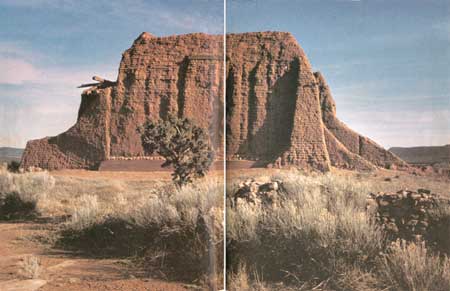

After the Pecos had gone, the pot hunter, the scavenger, and the transient pretty much wrecked the place. A few sorry souls haunted habitable corners of the ruins for a decade or so—Matt Field's wizened goatherd, fugitive Juan Cristóbal Armijo wanted for murdering a Mormon peddler, the old woman and her comely daughter of "dark and meaning eye" who so titillated Richard L. Wilson as he gathered his Short Ravelings from a Long Yarn, or Camp March Sketches of the Santa Fe Trail. One unfortunate of the 1841 Texan-Santa Fe expedition, Thomas Falconer, remembered being herded with his fellow captives into the ruins of Pecos pueblo. "It is a walled enclosure, in which a few persons lived; but," he added, "the houses within were made more ruinous than on our arrival, by the Mexican soldiers, who, made fires of the materials." The north end of the main quadrangle stood longest. "The dwellings," James Madison Cutts said in his journal entry of August 17, 1846, "were built of small stones and mud; some of the buildings are still so far perfect as to show three full stories." A comparison of Stanley's sketch with the rendering by German artist Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen twelve years later illustrates the rapid moldering of the pueblo proper. Already by 1858, great mounds buttressed and filled the walls of the lower stories, mounds that would continue to grow and thereby entomb for the archaeologist what lay beneath. The same dozen years also brought the hulking church to the brink. Möullhausen, like almost every writer before him, commented on the woodwork in the building, carved and painted, especially the hefty beams and corbels. Above them, the roof had begun rotting away, and, in places, the sunlight shown through. The German's painting of the Pecos church in 1858 is the last to show the structure essentially intact. Shortly thereafter a Polish squatter named Andrew Kozlowski tore into it. His widow told Bandelier that when they had arrived in 1858 the beams were still in place. Kozlowski pulled many of them down to build houses, stables, and corrals. He also, she said, tried to dig out "the corner-stone," but in that he failed. In 1866, when landscape painter Worthington Whittredge portrayed the building's southern profile, nave roof and towerswere absent.

By Bandelier's day, the church had definitely gone to ruin. "In general," he wrote in 1880,

Even in ruin it was impressive. "I am dirty, ragged & sunburnt," Bandelier exulted from Pecos on September 5, 1880, "but of best cheer. My life's work has at last begun."

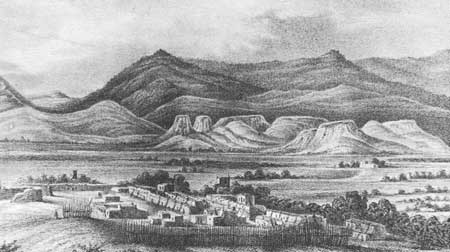

The great Swiss-American pioneer ethnologist had only just arrived in the Southwest a few days before. From the train, he had caught his first glimpse of Pecos. Its setting was all colors:

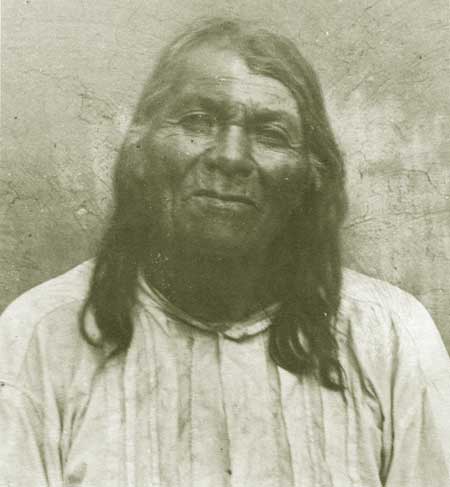

To alert the less observant tourist, the Santa Fe Railway Company later erected on the north side of the tracks opposite the ruins an immense signboard proclaiming Pecos a wonder of the Southwest. In a sense, Bandelier did the same thing. His notably meticulous report—even to mention of the broken Anheuser-Busch beer bottles—based on ten exhilerating days of field investigation, alerted the archaelogist to the potentials of the Southwest. Curiously, Bandelier never followed up his initial study at Pecos. Eight years later, in 1888, he did meet at Jémez a trio of the Pecos remnant: José Miguel Vigil, Agustín Cota, who was at the time governor of Jémez, and José Romero. Aside from the Spanish names of six other Pecos Indians "still alive," and the native names for Pecos pueblo and four nearby ruins, he got very little out of them. Ethnohistorian Frederick Webb Hodge and archaeologist Edgar L. Hewett, who interviewed Vigil and Cota on several occasions between 1895 and 1902, did better. Hewett's 1904 article "Studies on the Extinct Pueblo of Pecos" listed twenty-two Pecos clans, discussed the archaeology of the upper Pecos Valley and the aboriginal range of the Pecos people, fixed the year of the abandonment at 1838, and recorded the native names of the seventeen refugees. Relying mainly on Pablo Toya, son of the deceased Juan Antonio, the persistent Mrs. Parsons added three more refugees and figured out genealogies.

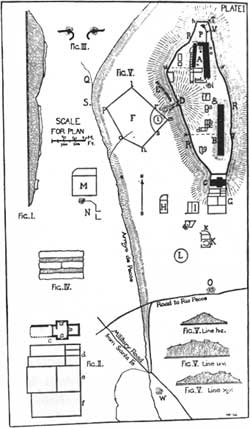

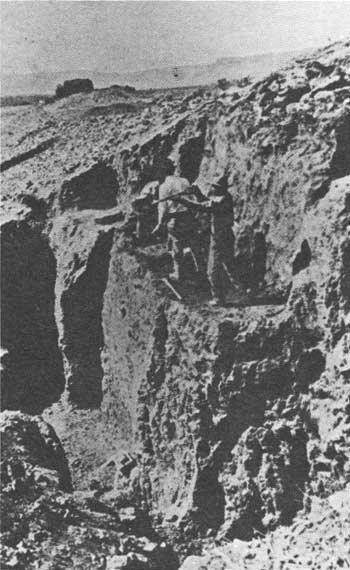

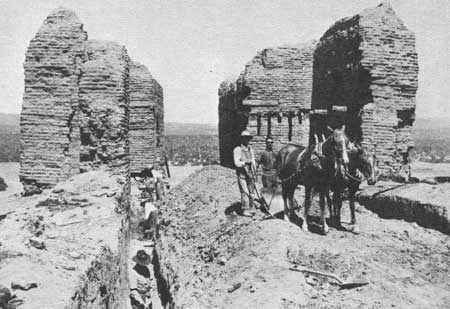

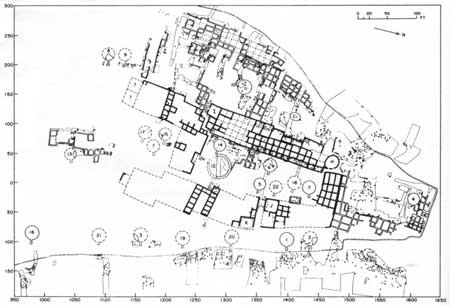

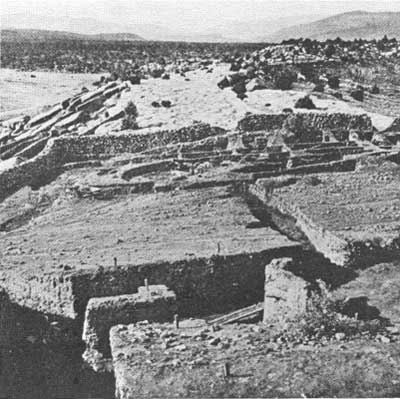

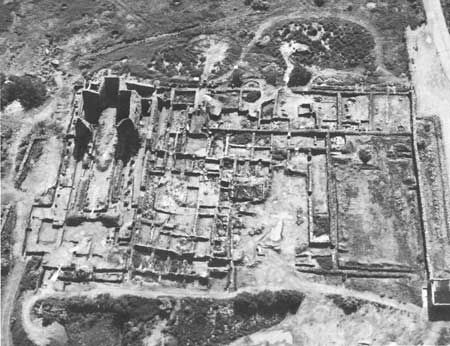

Meantime, Pecos had been on display in California. A sixteen-foot-long model of the mesa top showing reconstructed church, South Pueblo, and main Quadrangle was a prominent attraction in the New Mexico building at the 1915 San Diego Panama-California Exposition. That same year, the trustees of Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts, resolved to excavate a site in the Pueblo area "large enough, and of sufficient scientific importance, to justify work upon it for a number of years." No one at the time quite guessed what the excavation of Pecos would yield. The thirty-year-old Harvard man appointed to direct it, only the sixth archaeologist to earn a Ph.D. in the United States, already had wide experience in the Southwest. He had suggested Pecos. Genial, modest, penetrating, and full of ideas, Alfred Vincent Kidder knew what he was after. Solidly trained in field method by a prominent Egyptologist, he was spoiling to raise New World archaeology above the old antiquarianism that concentrated on the collecting of showy specimens for museums and to move it in the direction "of systematic, planned research and of detailed analysis of data followed by synthesis." Previous excavations in the Southwest had resulted in an array of loose pages. At Pecos, which proved vastly richer and more complex than he had imagined, Kidder found the index. Digging in the dark, loamy soil that had built up and eventually buried the cliff on the east side of the pueblo, in what Kidder called "the greatest rubbish heap and cemetery that had ever been found in the Pueblo region," he uncovered neatly statified deposits containing quantities of broken pottery, pottery that could be classified,

When he got past the middens to the pueblo ruins themselves, Kidder discovered not the large single structure he had anticipated, but another sequence. The historic town of "wretchedly bad masonary" had been laid out on top of the tumbled walls of previous buildings, and the latter over at least two earlier layers of dwellings. This situation thrust him into a study of the "mechanics of pueblo-growth." In the course of ten summers at Pecos between 1915 and 1929, two events broadcast the coming of age of American archaeology. The first was the publication in 1924 of Kidder's An Introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology, with a Preliminary Account of the Excavations at Pecos, which has been called "the first detailed synthesis of the archaeology of any part of the New World." The second, in August 1929, was an informal, precedent-setting reunion of Southwestern field researchers at what became known as the "Pecos Conference." Here, at Kidder's invitation, he and his colleagues reached fundamental agreement on cultural sequence in the prehistoric Southwest, definitions of stages in that sequence, and standardization in naming pottery types. When the fiftieth anniversary Pecos Conference convened in 1977, there was high praise for Alfred Vincent Kidder, who in pursuit of his vision made Pecos the most studied and reported upon archaeological site in the United States. Preservation also came. Simultaneous with Kidder's opening field session in 1915, Jesse L. Nusbaum of the Museum of New Mexico had directed the removal of tons of debris from the old church, which, roofless and cruelly weathered, still stood nearly its full height at the transept. His crews then stabilized undercut walls with massive cement footings. In 1920, before Gross, Kelly and Company sold its share of the Pecos Pueblo grant, Harry W. Kelly and Ellis T. Kelly, his wife, along with the company deeded an eighty-acre tract, including mission church and pueblo ruins, to Roman Catholic Archbishop Albert T. Daeger. As agreed, Daeger in turn deeded the historic parcel to the Board of Regents of the Museum of New Mexico and the Board of Managers of the School of American Research in Santa Fe. Created a New Mexico State Monument in 1935 and a National Monument in 1965 (and redesignated as a National Historical Park in 1990), enlarged several times over by a donation of land from Mr. and Mrs. E. E. Fogelson, owners of the Forked Lightning Ranch, Pecos in 1976 is well on the way to becoming what Kidder envisioned in 1916—"an educational monument not to be rivalled in any other part of the Southwest."

This is the day of "environmental statements" and "interpretive concepts" and "master plans," of "resource management" and "visitor use." Under the superintendence of the National Park Service, excavation, research, and stabilization continue. In 1967, when archaeologist Jean M. Pinkley, trenching to find a wall of the eighteenth-century porter's lodge as described by Father Domínguez, hit instead the buried rock foundations of Fray Andrés Juárez' mammoth church, she laid bare a truth that had eluded Bandelier, Hewett, and Kidder. At the same time, she made seventeenth-century pious chronicler Alonso de Benavides, who had portrayed the Pecos church in superlatives, less the liar.

"The view of Pecos, as it now lies, without the least addition," wrote Lt. J. W. Abert in his journal entry for September 26, 1846,

On a similar day, August 3, 1975, closest Sunday to the feast of Our Lady of the Angels, a procession strung out along the path west of the convento ruins on the way to celebrate Mass in the roofless church. The clouds and their effect were just as Abert had described them, the shades of color and light just as fleeting. The tenth archbishop of Santa Fe, smiling, walked in front. Behind him, the men of Pecos village carried the restored painting of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles as a banner. From Jémez, a delegation of the Pecos remnant had come to take part, and from Washington, D.C., New Mexico's two United States senators. In one sense, the scene was complete in itself—the pageantry of the movement, the tolerant presence of three cultures, the glory of the natural surroundings—enough to delight anyone. Yet for the spectator who knew something of the history of the living Pueblo de los Pecos, another dimension lay behind the scene, a dimension that stretched far back beyond the time when the people and the place had parted company.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||