Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Gateway Pueblo The plains had always been a paradox. At once a source of riches, of hides and meat and ideas, and of death, of thieves and raiders, the benefits to the Pecos had long outweighed the detriments. Sad for them, as for the Saline pueblos before them, the scales reversed in the eighteenth century. By 1750, their vital locale at the gateway between pueblos and plains had become a curse instead of a blessing. Sorely weakened by internal dissension and emigration, by pestilence, warfare, and interruption of trade, the "citadel" that once fielded five hundred warriors and struck fear into neighboring peoples now depended for defense on Spanish military aid and diplomacy. Not that the Pecos fighters had gone soft. They were just too few. As late as the 1690s, it can be argued that the Pecos held the balance of power, that without their aid, Diego de Vargas might well have lost New Mexico. Vargas said almost as much himself, and he rewarded the Pecos accordingly. Yet with the death of the two enduring Pecos dons, Felipe Chistoe in the mid-1720s and Juan Tindé in 1730, that era passed. A half-century later when Juan Bautista de Anza rode down to Pecos to negotiate a peace and save New Mexico from the ravages of invasion, it was not a Pecos he embraced, but a Comanche.

By dint of its location, the pueblo of the Pecos maintained a strategic importance despite its declining population. The Spaniards could not afford to lose it. Otherwise, Santa Fe lay open from the southern plains. The place, then, became more important than the people, a shift reflected even in the Spaniards' name for the pueblo. At the beginning of the century they invariably called it el pueblo de los Pecos, the pueblo of the Pecos people. Later it became simply el pueblo de Pecos, Pecos pueblo, the place. More and more the significance of Pecos was seen in its relationship to Hispanic Santa Fe. Daring Frenchmen who blazed "the Santa Fe Trail" in the 1730s and 1740s thanked God to reach Pecos, but they did not stop there. Those imperial strategists in Mexico City and Madrid who conceived defense plans embracing the entire northern "provincias internas," from the Mississippi Valley to the Californias, could see that a road from San Antonio or from St. Louis struck the province of New Mexico at Pecos. It was a port of entry. Then, in the very last years of the century, with the settlement of San Miguel del Vado at the river crossing ten leagues east, even that distinction was lost.

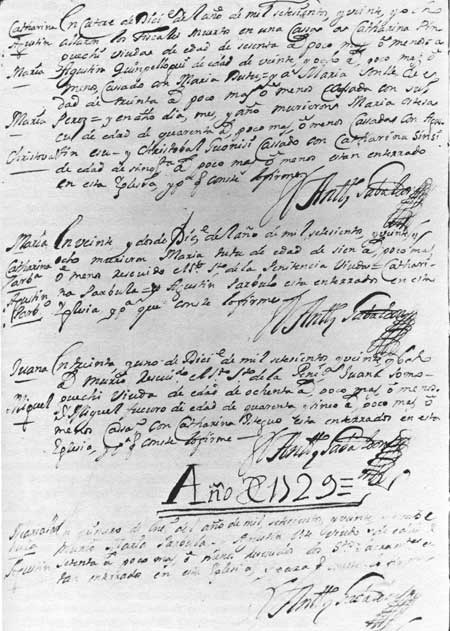

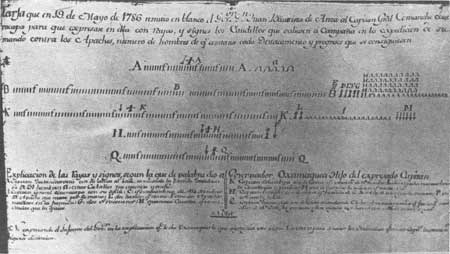

The Pecos as Auxiliaries The Pecos did not fade overnight. The Spaniards continued to think of them very much as people, albeit exploitable second-class people, well into the eighteenth century, as long as their pueblo remained a major center of trade with the Plains Indians, as long as Pecos auxiliaries fought at their side. Until the 1730s, the Pecos on any given campaign were likely to outnumber the fighting men from any other pueblo. Routinely, Fray José de Arranegui noted on July 1, 1702, the death of Francisco Fuu, husband of María Tugoguchuru, killed by the Jumanos "when Gov. Pedro Rodríguez Cubero sent out 56 Indians from this pueblo." Early in the spring of 1704, don Felipe Chistoe and forty-six Pecos answered the call for what proved to be Diego de Vargas' last campaign, three times as many men as from any other pueblo. A decade later, Governor Flores Mogollón dispatched a much larger force into the same area against the same foe, into the Sierra de Sandía against Faraón Apaches. This time, of the 321 auxiliaries summoned from fifteen pueblos to the rendezvous at Santo Domingo, one hundred were Pecos. Zia with thirty-six was second. [1] They must have gone out on dozens of such campaigns. There were almost certainly Pecos with Sargento mayor Juan de Ulibarrí in 1706 on his touted trip to El Cuartelejo, more than a hundred leagues northeast of Santa Fe. Again that year, word had reached the villa from the Picurís remnant who had fled from Vargas back in 1696 and since then had been living among the "Cuartelejo Apaches." They wanted to come home. In response, Governor Cuervo y Valdés charged Ulibarrí to ransom them and escort them back. Ulibarrí, Cuervo's alcalde mayor of Pecos and newly refounded Galisteo, named Capt. José Trujillo substitute alcalde for the duration, bolstered his forty Hispanos with a hundred Indian auxiliaries "from the pueblos and missions of this kingdom," and set out north from Santa Fe in mid-July. In seven weeks he was back. Not only had he seen El Cuartelejo and entered into friendly relations with the local Apaches, but he had also learned of Frenchmen among their enemies, the Pawnees, and had taken possession of this delightful region for Spain. Moreover, he had "liberated" the famous leaders don Lorenzo and don Juan Tupatú and some sixty Picurís, a few of whom settled at Pecos. [2]

Faraón Apaches as Friends and Foes Whoever the Pharaoh, or Faraón, Apaches were to the Spaniards, they cannot have been so confused in the minds of the Pecos. Perhaps at times, the same Apache band did alternately raid and trade at Pecos. More likely, it was the Spaniards' loose classification, their admission that "they all look alike," that made the Faraones the special friends of the Pecos one minute and the foes of Pecos auxiliaries the next. There is no doubt from the Vargas journals that certain Plains Apaches, sometimes labeled Faraones, reestablished trade at Pecos during the 1690s, a trade they maintained into the 1730s, at least until the Comanches convulsed the southern plains. It is also clear from burial entries at Pecos and from other sources that other Apaches, also termed Faraones, preyed on the Pecos during this same period. They struck any time of year without warning. Diego Sunchan, a married man, died in July 1697 a quarter-league from the pueblo when "the Apaches slit his throat" or decapitated him. On March 6, 1701, Father Arranegui buried Pedro Pui, about twenty-four, an orphan, "killed by the Apaches at the river." He buried four more victims, one a woman, in the spring of 1703. In August 1704, Apaches killed Francisco Antonio "and brought in his body." The body of Francisco Guatori, unmarried, the fourth death attributed to Apaches in 1705, "did not turn up, only his bones." Because of a lost book, the burial record at Pecos breaks off abruptly early in 1706 not to resume until mid-1727. Meantime, in 1711, the Marqués de la Peñuela asked the Pecos to confirm that he had responded with soldiers "when their enemies the Apaches have done them harm, as he did when they killed don Pedro, native governor of the pueblo, and Lt. Col. Juan Páez Hurtado went in pursuit." [3] If the Spaniards were confused, the Pecos themselves made a clear distinction between the Faraones of the plains and the Faraones who regularly took refuge in the Sierra de Sandía. The latter they branded "thieving Indian pirates" and murderers. In August of 1714, while many of the Pecos men were on campaign in the Sandías, seven Apaches, identified by the Pecos themselves as members of the Sandía band, showed up at the pueblo. A couple of older men and five women and children, this was no war party. No matter, the Pecos were for killing them on the spot. José de Apodaca, agent of Alcalde mayor and master blacksmith Sebastián de Vargas, said no. He notified Vargas who came down from Santa Fe and took this motley bunch back with him to appear before Governor Flores.

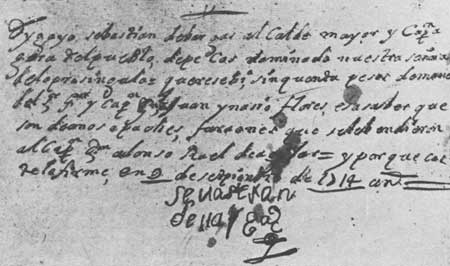

Agustín, a Pecos who knew both the Apaches' language and Spanish, interpreted, hardly an impartial officer of the court. Through him, all the Apaches told different stories. Their captain had sent them to see if the Pecos were alert because others were coming to steal. They had come peacefully seeking food. They wanted to trade. They had come from the Cerro de las Gallinas beyond the Sandías. They had come from the Cerro de las Cebollas. There were twenty tents with their captain. There were two women with their captain. With that, interpreter Agustín "stated that he had told the truth and just what the Apaches had said, neither adding nor omitting a thing." A couple of days later don Juan Tindé and several of his people stood before the governor to explain why they had wanted to kill these Apaches. Felipe Chistoe interpreted for those who did not speak Spanish. All agreed. These Faraones had killed a Pecos during the time of Governor Cuervo y Valdés (1705-1707). Besides, "they are thieving Indian pirates who make their base in the Sierra de Sandía from which they sally forth to rob horses and cattle from the pueblo of Galisteo, said pueblo of Pecos, Santo Domingo, Bernalillo, and other ranchos." Even the Apaches who came in peace to trade at Pecos knew the Faraones of the Sandías to be bad horse-stealing Indians. Governor Flores did not vacillate. He sentenced the two adult males to work on an ore crusher where they were to be kept shackled to prevent their return to thievery. He gave an old woman to a citizen of Santa Cruz de la Cañada. The remaining two women and two boys were to be sold in Sonora or elsewhere to persons who would try to make Christians of them. The governor accepted Alfonso Rael de Aguilar's offer to buy them and transport them out of New Mexico for two hundred pesos, a sum he promptly distributed as follows: fifty pesos to the Third Order of St. Francis, fifty to Alcalde mayor Vargas for bringing in the Apaches, twenty-five to the governor's secretary for his services, and the remainder to the honest poor. [4] A year later when the governor held councils of war to consider a punitive expedition against raiding Plains Apaches, called variously Chipaynes (sometimes Chilpaines or Chipaindes), Limitas, Trementinas, or Faraones, the native governor of Taos pointed out a conflict of interest. The Pecos, he said, should not be allowed to go. They and these Faraones were virtually one people. Back when the Pecos were reduced, this Taos averred, the Faraones had left them and fled out onto the plains. Since then, these fugitives had been wont to mingle during the trading at Pecos and then, on leaving, to steal from the district of Santa Cruz de la Cañada, from Picurís and Taos, and from the friendly Jicarilla Apaches who came to trade at Taos. Naturally the Pecos would warn their old partners. Capt. Félix Martínez also objected to the Pecos going, but for a different reason. With the presidio undermanned and the Pecos auxiliaries out on campaign, he thought the Faraones might circle round and attack the weakened pueblo. But the Pecos did go, thirty of them under Chistoe and Tindé "with muskets." And they took the blame. The whole force, 37 soldiers, 18 settlers, and 146 Pueblo auxiliaries, commanded by Juan Páez Hurtado, left from Picurís on August 30, 1715, picked up Jicarilla allies en route, and ended up on the Río Colorado, the Canadian of today, only to discover that the Apaches they were after had decamped. With supplies running low they turned back. "I presume," wrote the disappointed Páez about his vanished enemy, "that from the trading conducted at Pecos they got word that the Spaniards were coming after them." Not only did the Páez fiasco reveal the heated rivalry between Taos and its regular Apache trading partners on the one hand and Pecos and its Plains "Faraón" partners on the other, but it also said something about the Pecos. Plainly they knew one Faraón from another. [5]

Trade Fairs at Pecos The annual fall trade gatherings at Pecos, sometimes called rescates and sometimes ferias, held up as long as the Plains Apaches did. Governor Peñuela, accused of usurping "the trade that comes to the pueblos and frontiers of Taos, San Juan, and Pecos," answered his critics in 1711. The Pecos, at Peñuela's bidding, testified

Peñuela, at pains to show how his employment of Pecos Indians on church construction in Santa Fe benefited them in their trading, explained why he had paid each worker two awls instead of the usual trade knife. Earlier in the year, he had sent to Parral for thirty dozen "Madrid knives." These, along with many other goods on the governor's account, had been lost en route in an attack by hostile Suma Indians. Unable to acquire any iron elsewhere, Peñuela ordered some iron bars intended for use in the mines broken up as well as plow shares for the presidio's fields. From this, master blacksmith Sebastián de Vargas made a great quantity of awls, two of which the governor gave to each Indian.

Vargas, in 1711 lieutenant alcalde mayor of Pecos and Galisteo, swore that he had seen the Pecos trading the awls to good advantage with heathen Apaches for buffalo or elk skins and meat. "He also saw how some of said Pecos Indians were taking to the Apaches a bowl-shaped basket of tobacco and with it an awl for which they got a skin." [7] When the Chipayne Apaches showed up at Pecos in August 1711 with their skins and captives to trade "as they customarily do some years," they sold out quickly and left. Later Capt. Juan García de la Riva discovered that he had bought not a heathen Plains Indian boy but rather a Spanish-speaking Christian lad abducted from the Rio Grande missions of Coahuila. Ordering everyone else who had acquired a captive from the Chipaynes to bring him or her in for examination, Peñuela identified three more Christians. He warned their new owners to treat them as such, then wrote to the governor of Coahuila via the governor of Nueva Vizcaya and the corregidor of Zacatecas asking what he should do. The response, if any, has not come to light. [8] It was customary in New Mexico for the alcalde mayor of the district to open and preside over the trading. As unobtrusively as possible, he was to set fair prices and to maintain order. All parties presumably benefited from such supervision and the heathens were spared "the excesses and injuries that arise from the insatiable greed of the citizens of this kingdom." Often Indians who had come in peace to trade had been provoked to anger by the Hispanos' misdeeds. The trouble was that hardly anyone could agree on the line between beneficial regulation of trade and monopolistic exploitation by the governor and his alcaldes mayores. The citizens were always complaining of interference by the alcaldes. In 1725, Gov. Juan Domingo de Bustamante, later accused by the friars of lining his pockets in every conceivable way, decreed for the record that no alcalde obstruct or alter the customary free trade in captives brought by the heathens to the Taos Valley, San Juan, and Pecos. He dispatched the original to each of the three alcaldes in turn for his acknowledgement and signature. As was standard, each official made a copy and posted it on the door of the local casas reales. Alcalde mayor Manuel Tenorio de Alba tacked up the decree at Pecos on October 1. [9]

Trade in Captive Indians

Although in volume and worth the trade in buffalo hides and fine tanned skins far exceeded the "ransom" of non-Christian captives, no item was more important to the local Hispanos or more avidly sought after than these human piezas. Mostly they were children or young women, for their men died fighting, were put to death, or were too tough to "domesticate." No Hispano of New Mexico, however lowly his station, felt that he had made good until he had one or more of these children to train as servants in his home and to give his name. Men wanted to present them to their brides as wedding gifts. They were as sure a symbol of status as a fine horse. Baptized and raised in Hispano homes, these captive Apache, Navajo, Ute, Comanche, Wichita, or Pawnee children assumed the culture of their new surroundings and lost their tribal identity, or, as the anthropologists say, they were acculturated and detribalized. When they came of age, they generally married others of their kind or, in some cases, a Hispano or a Pueblo Indian, further blurring their heritage. As a class in New Mexico they were called gen&icute;zaros. When captive children were acquired by the Pueblo Indians, they were of course baptized and given a Christian name to satisfy the friars, but they remained Indians so long as they kept to an Indian environment. Nor did they seem to lose their old identity so fast, at least not for a generation or so. It was the same with foreign Pueblos, who turned up in the Pecos books as Miguel Zia, Lorenzo Picuri, Antonio el Queres, or Antonio Tano; hence, Catalina la Yuta, Juan Antonio Jicarilla, and Juana Manuela Jumana. Although the exclusiveness of Pueblo society naturally limited the practice of keeping captives among them, some Pueblos did. On December 28, 1743, for example, after Fray Agustín Antonio de Iniesta had baptized two Apache girls at Pecos, he noted that "both of them belong to Antonio, the governor of this pueblo, who stood as godfather" Coronado had found slaves from the plains living at Pecos. Along with trade contacts, "under the eaves" of their pueblo and out on the plains, the presence of these foreigners among them may have "contaminated" the typical Pueblo communism with Plains individualism and self-assertiveness, at least among members of the more susceptible trading faction. Whatever the effect, it must have continued throughout the eighteenth century, for the missionaries assigned to Pecos kept baptizing, marrying, and burying a potpourri of Utes, Pawnees, Wichitas, unspecified Apaches, Jicarilla Apaches, Carlana Apaches, and a good many others identified simply as the children of "heathen parents." [10] For the Franciscans of New Mexico, the traffic in heathen children presented both an opportunity and a dilemma. The superiors vacillated. In 1700, the custos forbade the friars to acquire the ransomed offspring of Apaches or other heathens, even for the sake of making Christians of them or training them to serve in the convento. It laid the missionaries open to charges of acquisitiveness, trading, and keeping human chattel. The prohibition was reiterated often enough to indicate that the practice continued. In 1738, Custos Juan García did so once more: "Again we direct that the religious abstain from attending the trading, much less from acquiring piezas to sell and going armed for this purpose." [11] Yet, in 1749, Custos Andrés Varo conceded that they still did so.

Rowdy Traders at Pecos, 1726 A ruckus at the Pecos "fair" early in August, 1726, illustrates how fights could break out between an officious alcalde mayor and greedy traders. To hear Alcalde mayor Manuel Tenorio tell it, he was simply doing his duty, opening trade between the heathens and the many Hispanos who had collected that day and setting prices "favorable to the citizenry as is customary." But this time, a rowdy bunch of traders led by twenty-three-year-old Diego Manuel Baca of Santa Fe cut him short. Scandalously ignoring Tenorio and the office he held, they set up shop on their own and "in their ambitious greed" commenced trading straight-away. Seeing their hostile mood and how many of them there were, the alcalde judiciously with drew and looked for witnesses who would testify to this outrage. Coincidentally, don Pedro de Rivera, appointed by the viceroy to conduct an exhaustive inspection of northern frontier defenses, was still in Santa Fe. A Spanish-born member of his party had commissioned Alcalde mayor Tenorio to get him a good heathen child during the trading at Pecos. The Pecos missionary, Fray Antonio Gabaldón, also wanted a pieza pequeña. When the heathens arrived laden with buffalo meat to trade to the Pecos but with only a few captives, Tenorio's attempt to select the best two for his customers before opening the trading to anyone else evidently set off the row. Baca incited the others, yelling that the trading was for the people not for government officials. Pushing and shoving, they bid the four or five captives up to three and four horses each, plus bridles, "getting the worse of the bargain." It served them right, said Tenorio, who recorded the testimonies of four witnesses in his faltering hand and sent them off to Governor Bustamante. [13] Meantime, the aggrieved citizenry had prevailed upon certain of the friars to lay bare before Inspector Rivera the avaricious, stifling, illegal trade practices employed by Bustamante and his alcaldes to squeeze the New Mexico turnip dry. When the governor found out, according to one friar, his pleasant toleration of the Franciscans turned to mortal hatred. [14] Among the humble exports packed south by New Mexico's "merchants," buffalo hides and bales of tanned skins acquired in trade at Pecos and elsewhere ranked high. Up through the 1730s and 1740s, the era of Procurador general fray Juan Miguel Menchero, the Franciscans still freighted mission supplies north in wagons leased from private contractors, and merchants, both importers and exporters, still shipped their goods by agreement with the friars. Some New Mexicans made annual trips to the government-run stores in Chihuahua. Apparently certain of the friars were tempted too. In a report to Menchero, one conscientious missionary suggested that "the religious not be permitted to leave New Mexico for the villa of Chihuahua with the citizenry or for any other reason because this is usually [an excuse] to trade in tanned skins, buffalo hides, and other goods, all of which is foreign to the religious state." [15]

Later in the century, the great annual exodus to Chihuahua, the cordón or conducta as it was called, a raucous party of four or five hundred New Mexico traders and stockgrowers, with mule trains, soldier escort, and countless sheep, still carried the hides and skins from the plains. By then, however, Taos had far outstripped Pecos in volume. The reasons were several, the same ones that account for the pueblo's steadily declining population. Certainly the most dramatic was the appearance of a hard-riding, hard-fighting Plains people who began to war with the Pecos in the 1730s and who favored Taos for trade. Not that this people killed so many Pecos—a misconception invented by Governor Vélez Cachupín in 1750—but rather that they so turned the southern plains world upside-down that the Apache trading partners of the Pecos, their suppliers, were scattered about like chaff in the wind. This people was the Comanche. The Rise of the Comanche Nation The Comanche did not spring at full gallop from the head of a mythological buffalo. Their advent was almost meek. Drawn out of the basin and range country west of the Rockies by trade, horses, and the plains, they arrived in New Mexico about the turn of the eighteenth century in the tow of the Utes, fellow Shoshonean speakers. Almost immediately, allied bands of Utes and Comanches began contending with the semi-sedentary Jicarillas for hunting and trading grounds. By the second decade of the century, they had these Apaches begging the Spaniards for baptism. Their horse stealing under guise of peace, their murderous raids on the northern settlements, and their interruption of Apache trade had the Spaniards cursing their "barbarity." In 1719, Governor Valverde resolved to teach them a lesson. Mustered at Taos in September, this was no token force—sixty presidials, forty-five settlers, and 465 Pueblos, later joined by nearly two hundred Apaches. This was war. Fray Juan George del Pino of Pecos rode as chaplain. Strung out, Spaniards in front, pack animals in the middle, and native auxiliaries at the rear, with scouts ranging the flanks, they advanced northeastward through the pleasant valleys of Jicarilla and Carlana Apaches who pointed to the ravages committed by the enemy. Near the Arkansas River, they came on several deserted Comanche camps marked by cold fires and the tracks of travois poles leading away. The Cuartelejo Apaches clamored for Spanish aid, against Utes and Comanches, against Pawnees and Jumanos, against westward-moving Frenchmen who gave firearms to their enemies. But winter was coming. Valverde could not go on. He had not even seen a Comanche. [16]

By the time of Brigadier Pedro de Rivera's visit in 1726, the Comanches, "a nation as barbarous as it is warlike," had earned a notoriety of their own.

Displaced Apaches If the Pecos felt any pressure from the Comanches during the 1720s, the Spaniards did not record it. There is not even a reference to Comanches trading at Pecos. By the mid-1730s, however, the disruption these new plainsmen were causing had begun to strain the symbiotic trade relationships the Pecos had long enjoyed with certain Apache bands. Over the years to come, the quiet dissolution of this trade probably figured more heavily in the decline of Pecos than all the notorious Comanche assaults put together. [18] For the first time, displaced Jicarillas, formerly the special allies of rival Taos, began to appear in the Pecos books. Something was certainly going on during January 1734 when Fray Antonio Gabaldón catechized, baptized, and buried in the Pecos cemetery five Apaches. One he said was "a captain of the Apaches." Three were Jicarillas: a woman about ninety who had suffered an arrow wound in the heart, a boy, and a little girl. The following month he baptized another Jicarilla child "of heathen parents." These refugees, running from Comanches or other Apaches, had sought shelter at Pecos. In 1738, Fray Juan George del Pino, assured by the interpreter and the Pecos catechists of a Jicarilla woman's constancy and "moved by charity and the fear of her ill health, administered to her the water of baptism in the manner and form prescribed by the manual for adults." She had been living at Pecos for three years. [19] Comanche Assaults But it was the assaults that made news. Even though the first two Pecos deaths attributed to Comanches occurred in 1739, the really newsworthy attacks began in the 1740s during the governorship of Joaquín Codallos y Rabal. Why the Comanches, or one division of them, wanted to destroy Pecos and Galisteo is not clear. Certainly the Pecos had long been associated in trade with Apaches, and now they harbored Jicarillas. Whatever the reasons for the Comanches' grudge, they came not merely to steal horses but to vanquish as well. Few details of the first blow survive. It fell on San Juan's Day eve, June 23, 1746. The Comanches fought as if possessed. With a burning log, they tried to fire church and convento. The Pecos beat them back putting up so stiff a defense that the attackers finally withdrew after killing a dozen inhabitants, including two women, three children, and three Jicarilla Apaches. They abduced a Pecos boy seven years old, and they took off with the pueblo's horses. Reacting with unusual speed Lt. Gov. Manuel Sáenz de Garvisu, with fifty presidial soldiers, some civilians, and Indians from Pecos and Galisteo, gave chase. They found the boy dead on the trail "from arrows and hatchet blows." As they began to close, the Comanches, slowed by the stolen horses, wheeled around "in a great multitude" to do pitched battle. More than sixty of the enemy died according to Spanish count. But of far greater concern to the governor, nine soldiers and one civilian were killed. In brash defiance, Comanches hit Galisteo two weeks later killing an old man who was herding some cows. Reporting to the viceroy, Governor Codallos told how the Comanches were guided by apostates from New Mexico who knew the waterholes, ranches, and settlements. Besides that, they were a numerous nation and so well disciplined in warfare that they had defeated other Plains tribes and taken their lands. Codallos wanted greater authority so that he could carry "open and formal war" to the Comanches' own country. Following normal procedure, the viceroy requested an opinion of the Marqués de Altamira, his chief military advisor. What riled Altamira was the loss of ten Spaniards without "more punishment to the enemy than killing about sixty of them." As a result, the Comanches were "elated, vainglorious, and proud," as their subsequent attack on Galisteo demonstrated. Emboldened by a succession of victories over other Indians, and now by this affront to Spanish arms, these Comanches were obviously taking the offensive. They were jubilant over killing one Spanish soldier, Altamira opined, even at the loss of a hundred of their own, "which because of their barbarousness and their numbers is of small consequence to them." In sum, the governor, utilizing Comanche prisoners and the good offices of the missionaries, should offer the barbarians peace. If they refused, he should "banish them from that entire area." [20]

A Battle at Pecos, 1748 Although he won a satisfying victory in 1747, the overall effectiveness of Governor Codallos' Comanche policy can be judged by what took place at Pecos on Sunday, January 21, 1748. The afternoon before, near sundown, a messenger, whose face betrayed anxiety, delivered a note at the governor's palace. Snow lay on the ground. The air was brittle cold. Codallos read the note. It was from Fray José Urquijo of Pecos. A large force of Comanches had massed at the Paraje del Palo Flechado, only two and a half leagues from the pueblo. Urquijo feared an attack. Codallos showed the note to Fray Juan Miguel Menchero, outspoken special agent of the Franciscan commissary general. Menchero had recently coordinated a large-scale Gila Apache campaign—a role unbecoming a friar, some of his brethren said. Menchero cursed the luck. He was sick. He would have to send his secretary Fray Lorenzo Antonio Estremera. Codallos ordered the drum beaten. It was getting dark. Most everyone was inside by a fire. "In a villa, the capital of a kingdom, where there are more than 950 Spaniards and mixed-bloods and more than 550 Indians," according to one report, "only 25 persons, counting citizens and soldiers, assembled." Ten of them he dispatched for horses seven leagues away. With the other fifteen and Father Estremera, he mounted up and headed for Pecos. It was hard going, Estremera recalled, "the night black, the road bad, and the snow deep." But they made it, about two in the morning.

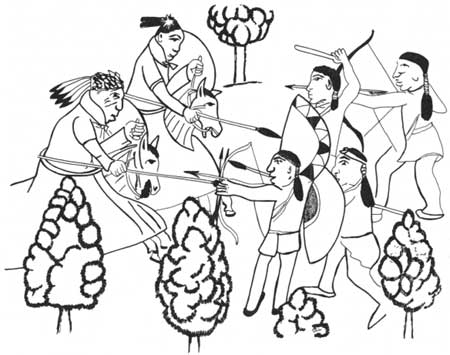

Heroics of Governor Codallos No one was asleep. The Pecos and their missionary were distraught, say the reports, all of which made Governor Codallos the man of the hour. Ascertaining first the direction from which the enemy was coming and roughly how many there were, more than 130, all mounted, he began giving orders. The Pecos assured him that Comanches did not attack at night. They had until daybreak. He told the pueblo officials to get the women, children, and old men up on the roof tops and bar all doors. A dozen of the old men waited in the convento to protect the missionary. The young men, the mocetones, armed with bow and arrows, shield, lance, and war club, rallied around him. There were about seventy, among them some heathen Jicarillas "of those who live in peace in the shelter of this pueblo." Through an interpreter, the governor explained his plan. Since all the pueblo's horses were out to winter pasture and those of the governor's men spent, they would have to go out against the Comanches on foot. It was absolutely necessary, he told them, that everyone stay together. They must not scatter. The rest of the night, while scouts kept watch around the pueblo, they remained under arms.

About eight o'clock, the Spanish-speaking Pecos stationed in one of the church towers shouted that the Comanches were coming up on the convento side, many more than a hundred, all on good horses. It was time. Swiftly they followed the governor through the gateway, soldiers, civilians, Indians, and Father Estremera, who had seen to their Christian preparation "with acts of contrition and general absolution for all exigencies." Taking up a position a short distance beyond the convento, everyone well together, they obeyed Codallos' order not to fire until the enemy committed himself, and then only on command. The Comanches advanced "with such an outcry and screaming to strike fear that only the presence of mind and energy of Gov. Joaquín Codallos, aided by God, could have overcome such boldness." When they were no more than a pistol shot away, the governor moved his men forward in order and the battle was joined. The Spanish "square" held. Firing several volleys point blank, using their lances and bow-men to good advantage, the governor's force repelled the cavalry assault, inflicting a goodly number of casualties. Startled, the Comanches withdrew a short distance "skirmishing with great agility." Most of them wore cueras, the protective leather coats, and carried a large shield, lance, bow and arrows, and some a sword or war club. During the lull, they picked up their dead and wounded, placing them across their horses. Meanwhile, eager to see what was going on, the old men Codallos had left in the convento told Father Urquijo that they would be right back. Slipping out and heading for a good vantage, they were spotted by one of two additional Comanche parties coming up to join the others. It was no contest. The Comanches ran them down. Eleven died. In addition, said Father Estremera, a Jicarilla had been killed in the battle, one civilian wounded, and a soldier's horse slain. The other two columns of Comanches rode in defiance by the governor a musketshot away and took their places with the rest. Now there were three hundred more or less. Promptly Codallos ordered his force to fall back on the convento little by little, the Indians first. The enemy watched. Just then on the road from Santa Fe, they saw the troops and extra horses coming to reinforce the governor. From a distance, the column seemed larger than it was. The Comanches withdrew to a hill a quarter-league from the pueblo. The men and horses from Santa Fe joined the others in convento and pueblo. A short while later, the enemy departed the same way they had come. "Thus it was assured," Father Estremera exulted,

That same afternoon Father Urquijo buried in the church the bodies of thirteen men who had died in the battle. The funeral rite was held next day. For the consolation of the Pecos, Codallos left a squad of soldiers. Six weeks later, when he wrote to the viceroy, he enclosed Father Estremera's sworn account of the battle at Pecos, so that his most excellent lordship, if he deemed it meet and proper, might commend the governor of New Mexico to the king. [21] The Scourge of Epidemic Disease Less newsworthy than the Comanche assault of 1748, but more lethal, was an unnamed epidemic that swept New Mexico late that summer. Sixty-eight persons died at Santa Fe between July and September. Father Urquijo was ordered to the villa to help. During his absence, at least fifteen Pecos children expired as well as three single men "without receiving the sacraments because," in the words of Fray Andrés García, "it is the custom of these mission Indians to notify the Father when there is no chance." The bunching of deaths in the Pecos burial books, more-or-less complete for the years 1695-1706 and 1727-1828, reveals major epidemics almost every decade:

And there were others. Over the years, epidemic disease claimed many more lives at Pecos than did the violent assaults of Plains raiders. [22] Against the Comanches, hero Codallos had won some and he had lost some. At a junta convened in 1748, the consensus was that this now formidable Plains people, despite their barbarous perfidy, should be permitted to trade at Taos. New Mexicans were not prepared to do without the skins, meat, horses, and captives only the barbarians could supply. Besides, it brought them within the sphere of Christian influence and saved their captives from probable death. [23] Vélez Cachupín Takes Over In the spring of 1749, Governor Codallos, praised by Fathers Estremera, Menchero, and Varo for his defense of Pecos, yielded to his successor. Young, full of ambition and not a little impetuous, don Tomás Vélez Cachupín was already in the habit of exaggerating his own merits and the faults of others. Writing to the viceroy after a year in office, Vélez Cachupín claimed that Comanches had killed one hundred and fifty Pecos Indians during the administration of his predecessor, between 1743 and 1749. [24] Picked up by two fervent Franciscans, equally prone to exaggeration and eager to embarrass the governors any way they could, suddenly the Pecos dead exceeded one hundred and fifty, and now at one blow!

A Massacre that Never Happened According to Fathers Juan Sanz de Lezaun and Manuel Bermejo, whose avowed purpose was to defend the persecuted and calumnated church and lay bare the incompetence and malice of New Mexico's governors,

There are, no doubt, elements of truth in this tale. The buffalo hunt and the carpentry have a valid ring. The account of Lieutenant Sáenz de Garvisu's chase squares precisely with the pursuit of June 1746. Some of the other stories the two friars told can be verified elsewhere. The Comanches, they said, had sent word early in 1750 that they were coming to Taos to trade. Warned that he should protect Galisteo and Pecos, the impulsive Governor Vélez Cachupín, "carried away by his caprice and greed," headed straight for Taos with all his soldiers. "In an instant the enemy struck Galisteo killing nine or ten Indians." In the Galisteo burial book, there is an entry of December 12, 1749, for eight men killed by Comanches attacking the pueblo. But nowhere is there corroborating evidence that more than a hundred and fifty Pecos died in a cleverly laid Comanche ambush." [26] In fact, there is evidence to the contrary. Father Menchero had estimated the population of Pecos at 125 families in 1744. Father Francisco de la Concepción González counted everyone in 1750, a total of 449 persons. The discrepancy is not great enough, nor does the 1750 census show an abundance of widows. If indeed "almost the entire pueblo of Pecos" had walked into a Comanche ambush in the 1740s, Father Manuel de San Juan Nepomuceno Trigo, who visited the pueblo as vice-custos in 1750, should have known about it. If he did, his statement in 1754 was a travesty. "The mission is invaded daily by the barbarians," wrote Trigo, "but the Pecos are such valiant warriors that the enemy is always defeated." [27] Still, the extravagantly heightened story that more than a hundred and fifty Pecos perished at one Comanche blow has persisted. It is the easiest way to explain the demise of the once populous pueblo—easy but erroneous. An example of the mid-century polemics of friars and governors, this exaggeration, suggested by Governor Vélez Cachupín and avidly embellished by the two Franciscans, should be taken for what it was—a blatant piece of propaganda. [28]

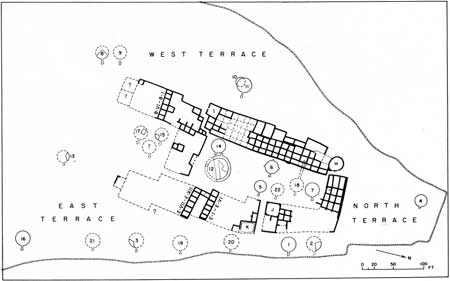

The Defense of Pecos and Galisteo After the assault on Galisteo in December 1749, Governor Vélez Cachupín took the Comanche grudge against Pecos and Galisteo seriously. Like his predecessor, he provided, on paper at least, detachments of fifteen soldiers at each pueblo. The large compound west of the Pecos convento, the so-called "presidio," probably dates from the 1740s and 1750s. Alcalde mayor José Moreno and a squad of soldiers had stood as marriage witnesses at Pecos as early as February 1747, although they may simply have been passing through on patrol. The friars confirmed that Governor Codallos had left troops to guard the pueblo after his heroics there in January 1748. That April, the military-minded Father Menchero wrote of fifteen-man detachments at both Pecos and Galisteo. Like others posted on outlying New Mexico frontiers, these detachments rotated and, like the parent presidio in Santa Fe, rarely if ever mustered at full strength. Vélez Cachupín, in his letter of March 1750, to the viceroy was the first to mention that he had fortified Pecos and Galisteo "with earthworks (trincheras) and towers (torreones) at the gates." Just what form the earthworks took is difficult to say, but the towers at the gates have been well substantiated at Pecos by archaeologist A. V. Kidder. In the north or main pueblo, he excavated four of them and identified a likely fifth, all "strategically placed" to command the four entrances. He termed them "guardhouse kivas," and he recognized that they were of late construction. But because he surmised that they were entered by a hatchway in the roof, because they were fitted out like kivas, and because they seemed not "to have been mentioned in the early Spanish accounts," Kidder refused to assign them a primarily defensive role. Probably he was right about their ritual significance, albeit secondary. The kiva-like fire pit, deflector, and ventilator simply provided the best heating system for these chambers. These, it would seem, were Vélez Cachupín's defensive torreones. [29] For the next half-century, until the Spanish settlements took hold at the river ford beyond, the governors guarded the Pecos gateway as best they could. To back up the arms of the Pecos Indians, which in 1752 consisted of 107 fighting men with 3,313 arrows, seventeen lances, four swords, and no cueras, they garrisoned the place sporadically and provided a small arsenal. In 1762, Alcalde mayor Cayetano Tenorio was responsible at Pecos for "1 small campaign cannon, 3 pounds of powder, and 250 musket balls." Somewhat expanded, the Pecos arsenal in 1778 included "18 muskets, 9 pounds of powder, 300 balls, 1 bronze cannon of two-pounder caliber with its carriage and other accessories, 4 balls of grape-shot, ramrod, and wormer." [30]

Comanches Hurl Themselves at Galisteo After treating and trading with Comanches at Taos in July 1751 and cautiously accepting their promises of peace, Governor Vélez Cachupín four months later saw his defenses tested by Comanches. The Indian scouts he employed to watch the approaches to Pecos and Galisteo had grown lazy. At dawn on November 3, 1751, without warning, a hell-bent army of three hundred Comanches or more "hurled themselves at the pueblo of Galisteo in an attempt to enter and sack it. The squad of ten soldiers which I had as a precaution there," Vélez reported,

Vélez Cachupín was furious. "My heart leaped," as he put it, "with an ardent desire to give them a taste of our arms and show them something else than the kindness with which I had treated them and dealt with them at Taos." Taking personal command of the punitive force, the brash young governor caught up with the Comanches on the sixth day, and by his own account handed them such a drubbing, killing a hundred or so and releasing the others after firm but kind words, that they contented themselves with peaceful trade for the remainder of his term. At this time, too, he learned that not all Comanches shared the grudge against Pecos and Galisteo, only certain leaders. [31]

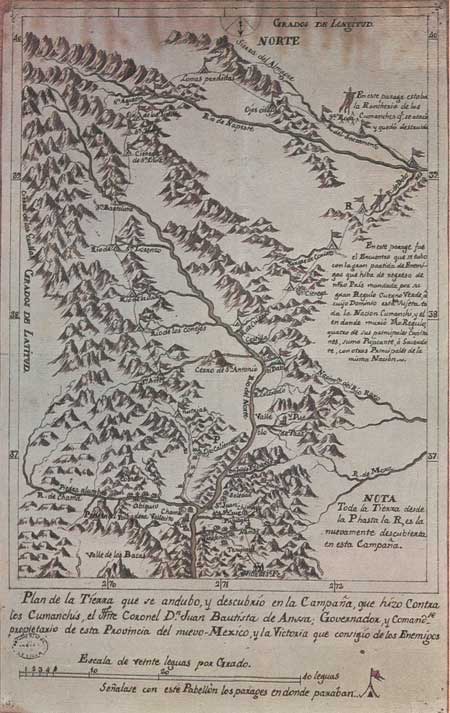

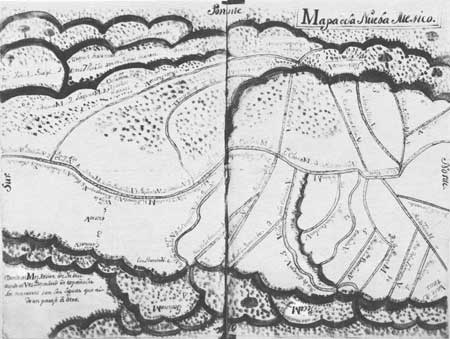

Diplomacy of Vélez Cachupín Despite the nasty things the friar partisans of ex-governor Codallos said about Vélez Cachupín, he, like Vargas before him and Anza after him, seemed to grasp intuitively the key to peace with the raiders: an active personal diplomacy backed by proven prowess in battle and a supply of gifts or trading opportunities. In his instructions to his successor, Vélez cautioned that the heathens would test him to see what manner of man he was. He must go to the fairs at Taos, conveying both confidence and friendship, and he must see to the Comanches' protection from the other tribes while trading, particularly from the Utes who had broken with them late in the 1740s. He must sit down and smoke with them, even "permit their familiarities and take part in their fun at suitable times." As for the displaced Plains Apaches, the Carlanas, Palomas, Cuartelejos, and Chipaynes, they should also be wooed. During the winter of 1751-1752, three hundred men of these tribes had taken refuge near Pecos. Although the friars baptized and buried some of their young and their infirm, these Apaches camped outside the pueblo and were never counted on Pecos censuses. Viewing them as a ready reserve in the event of Comanche hostility, Governor Vélez Cachupín had succeeded in keeping them there. He had sought to prevent a close alliance between them and the horse-thieving Faraones and Natagés, or Mescaleros. When the men ventured out onto the plains to hunt or rendezvous with relatives, they left their women and children in the safety of Pecos. These Apaches, he noted, made much better plains scouts than the Pueblos. The natives of Pecos and Galisteo who ably guarded the approaches to their pueblos should be kept alert. To insure the continuation of his successful policies at the eastern gateway, Vélez Cachupín recommended to the next governor that he retain Alcalde mayor Tomás de Sena, "who, because of his kindness, is greatly loved by the Indians. If he should be separated from them," Vélez counseled, "you could not find anyone who would wish to serve in that office." [32] Marín del Valle Wrecks the Comanche Peace But his successor did. Eager to put his own stamp on New Mexico affairs, Francisco Antono Marín del Valle, a vain, less bold individual who governed from 1754 to 1760, soon broke Vélez Cachupín's delicate web of alliances. The Apaches left the vicinity of Pecos. The Comanches took to raiding again. And the new alcalde mayor of Pecos and Galisteo went out on campaign. Don Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, lured north from El Paso by the offer of an alcaldía mayor, was an "engineer," soldier, merchant, painter, and, most important to Governor Marín, an accomplished map maker. After he had accompanied the governor on his visitation, Miera drew in 1758 an elaborate, illuminated map of the entire kingdom of New Mexico, one of a number he would compile and draw over the next quarter-century. On it, northeast of Pecos and north of the Río Colorado (the Canadian), he sketched a village of tipis. Below it, he wrote the words "tierra de Cumanches," and above it, drew a delightful leaping buffalo. Well to the south, on the west side of the Río Pecos not far from modern Fort Sumner, he labeled another cluster of tipis "Apaches Carlanes." [33]

While he held the office of alcalde mayor of Pecos and Galisteo between 1756 and 1760, don Bernardo claimed to have gone out on three campaigns against the Comanches. He also tried unsuccessfully to refound old cannon. He stood several times as godfather to Plains and Pecos Indians, as did his wife and his son, don Manuel. Before Governor Marín, his patron, stepped down, Miera painted for him a very special map in color showing New Mexico and "the provinces, enemy and friendly, that surround it." Replaced as alcalde mayor by Marín's successor in 1760, don Bernardo Miera remained in New Mexico for the rest of his life pursuing his varied interests, a prominent citizen who was never quite as prominent as he wished. [34] French Threat to New Mexico No problem exercised the governors of New Mexico more during the eighteenth century than defense against the heathen peoples on her borders, unless perhaps it was convincing the bureaucrats in Mexico City and Spain, who did not know a Comanche from a Pecos, how serious it was. It galled them that mere rumors of a few exotic Frenchmen somewhere out on the plains brought a more excited response than ten Apache raids. Diego de Vargas had used vague reports of a French threat in 1695 to win additional military aid for the colony. Other governors too were quick to relay every shadow of a Frenchman, real or imagined. They were out there, to be sure, trading guns and liquor and working their Indian diplomacy westward from the Illinois country and from the lower Mississippi Valley as well. A real scare came in 1719 when the European War of the Quadruple Alliance and the Valverde expedition to the Arkansas coincided. Although he never saw a Frenchman, the cautious Valverde reported what the friendly Apaches told him about French forts, guns, and milltary advisers among their Pawnee enemies. The next year when Pawnees annihilated the follow up expedition of Lt. Gov. Pedro de Villasur, some of the survivors swore that there had been Frenchmen among their assailants. [35]

The Mallet Brothers Thanks to the diplomacy of Étienne Véniard de Bourgmont among the Plains Apaches in 1724, the door to New Mexico lay open. But Bourgmont's return to France, Comanche-Apache warfare, and lingering resentment over the Villasur massacre intervened. Some illicit trade may have got through. For sure, in 1739, when Pierre and Paul Mallet and six or seven companions from the Illinois country dropped down via Taos to Santa Fe, they and their French contraband were cordially welcomed. Two of them, "Petit Jean" and Moreau, decided to stay, becoming Juan Bautista Alarí and Luis María Mona, the first a good citizen and the second an alleged rabble-rouser and sorcerer sentenced to die in the plaza of Santa Fe. The others, after months of riotous hospitality, returned—several back to Illinois and several down the Canadian, the Arkansas, and the Mississippi to New Orleans. The latter, departing through Pecos late in the spring of 1740, carried a letter from a friend in Santa Fe, don Santiago Roybal, the vicar, to his counterpart in Louisiana. Roybal wanted French goods badly, and he enclosed a list. He thought a lucrative trade could be got up between the two provinces across the plains "because we are not farther away than 200 leagues from a very rich mine, abounding in silver, called Chihuahua, where the inhabitants of this country often go to trade." That kind of talk excited the Sieur de Bienville, governor of French Louisiana. [36] The party Bienville sent to Santa Fe with a letter to the governor aborted, but a lone Frenchman, evidently a deserter from Illinois, dragged into Pecos early in June 1744. Governor Codallos told Sgt. Juan Felipe de Rivera to take a couple of soldiers to the pueblo of "Nuestra Señora de la Defensa de Pecos," enlist four Pecos Indians, and bring this unidentified intruder in "well secured." Interrogated in Santa Fe, he gave his name as Santiago Velo (Jacques Belleau, Bellot, or Valle?) and confessed that he was a native of Tours who had served as a soldier in Illinois. Codallos had no use for him. Dispatching the Frenchman's statement directly to the viceroy and Velo himself to the governor of Nueva Vizcaya, he washed his hands of the matter. [37]

Meanwhile, out on the plains, other Frenchmen were working for peace between the Wichitas, their allies, and the Comanches. With that accomplished in 1746 or 1747, the way again lay open to Santa Fe. By early 1748, Codallos had word that thirty-three Frenchmen had come to the Río de Jicarilla and traded quantities of muskets to the Comanches for mules. The next three Frenchmen, deserters from the Arkansas post who turned up at a Taos fair in the spring of 1749, were Governor Vélez Cachupín's problem. Two were carpenters by trade, the other a tailor, barber, and bloodletter. Vélez put them to work in the governor's palace and requested of the viceroy that they be allowed to stay.

Another pair arrived with an errant refugee Spaniard. Vélez cursed Gov. Gaspar Domíngo de Mendoza for entertaining the Mallet party, "the first who entered," and permitting them to return to French territory with favorable reports of New Mexico. [38] In November 1750, that mistake came home to roost. Four Frenchmen appeared at Pecos. One was no stranger. It was Pierre Mallet. He had set out from New Orleans with trade goods and letters from the governor and merchants of Louisiana. Only six days short of Pecos, the party had run into some Comanches who were spying on Pecos hunters. These jovial theives proceeded to despoil Mallet and his companions of most of their goods. With a dozen spent horses, they had made Pecos, where Lt. Gov. Bernardo de Bustamente y Tagle met them.

Taken into custody, they were escorted to Santa Fe and then on down to El Paso where Governor Vélez was waiting. He declared them illegal aliens and confiscated what goods they had left. These were evaluated and cried three times at public auction. Since no one bid on them, the El Paso merchant who had appraised them bought them himself for 420 pesos, six reales. The buyer was also a soldier, a painter, and a map maker, don Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, later alcalde mayor of Pecos and Galisteo. Vélez Cachupín used the money to send the prisoners to Mexico City, and that was that. [39] Poor Chapuis and Feuilli Just at noon on August 6, 1752, four days after the Pecos patronal feast, Fray Juan José Toledo was roused from his cell by a commotion. One of the servants motioned for him to come quickly. Outside the cemetery wall stood a couple of bedraggled-looking Europeans, one of them holding a French flag, or as Toledo described it, a piece of white linen on a stick with a cross on it. They and their guide Manuela, a run away Aa Indian servant of Esteban Baca, had been brought in from the Río de las Gallinas by Jicarilla and Carlana Apaches. [40] They had with them a string of nine horses carrying packs of sealed trade goods. Fray Juan, a thirty-six-year-old native of Mexico City knew no French. Jean Chapuis sounded to him like Xanxapy, very close if one sounds the Mexican x's, and Louis Feuilli, like Luis Fuixy. Ordering the goods unloaded and placed in the convento, Toledo saw to his guests, and then wrote a hasty note to Governor Vélez Cachupín, who had it the same evening.

Next day, Alcalde major Tomás de Sena reined up outside the convento. With sign language, he communicated as best he could that the Frenchmen had been summoned to appear before the lord governor in Santa Fe. Sequestering goods and horses, he packed the lot to the villa. The French tailor, who after three years in Santa Fe had picked up some Spanish, interpreted. The story the two told of sanction by French officials, their grand plans for opening trade, and the invoices of their merchandise, convinced Governor Vélez Cachupín that this was a matter for the viceroy. Their wares, all manner of dry goods, hardware, and fancy items, from silk garters and lace, hawk bells and mirrors, to embroidered beaverskin shoes and ivory combs, the governor sold at auction. When the viceroy decided that this was a matter for the king, hapless Chapuis and Feuilli, professing all the while their ignorance that such trade was illegal, were shipped off to Spain. Their attempt to open the Santa Fe Trail had been precisely seventy years too soon. [41] If other Frenchmen tried the Pecos gateway, their fates are not recorded. A decade later, as the Seven Years War wound down, France transferred Louisiana to Spain. Not only did the Spaniards inherit the elaborate French system of Indian diplomacy and subsidies, which would influence their own less liberal Indian policy, but also a vast and vulnerable new frontier. The contest for North America had come down to Spaniards and Englishmen. In New Mexico, meantime, it all hung on war and peace with "the barbarous Indians." The Rising Comanche Tide Between 1760, the year an anonymous imperial strategist recommended the creation of a separate northern viceroyalty in New Spain, and 1776, the year the crown set in operation the unified General Command of the Provincias Internas, almost a viceroyalty, the indios bárbaros ran wild.

At Pecos, trade with Apaches declined as Comanche hostility heightened. Although Jicarillas and their allies continued to live in and around the mountains north and east from Santa Fe and Pecos, no one mentioned Pecos "fairs." The pueblo's population fell from 344 to 269. The Franciscans neglected it. No longer did the friars bother to enter in the book of burials the Pecos dead. From time to time, however, they showed up in the governor's routine body counts. On January 13, 1772, for example, "9 Comanches killed two Indians of the Pueblo of Pecos who went out to look for their oxen." That was not the whole story, but it was a telling part of it. [42] Gov. Francisco Marín del Valle was an adherent of the eye-for-an-eye school, or better, many heathen eyes for one Spanish eye. During his administration and those of his two short-term successors, violence begot violence. To avenge the spectacle of Taos dancing with two dozen Comanche scalps before their very eyes, the Comanches rallied a huge war party and descended on the Taos Valley in August 1760. Their seige and plunder of the Villalpando house, where dozens of Spanish men, women, and children perished or were carried off alive, so impressed Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco that he related it in the legend of one of his maps nineteen years later. Although Marín's retaliation failed, Gov. Manuel Portillo Urrisola enticed the Comanches to Taos late in 1761 and succeeded in killing "more than four hundred." By "this glorious victory," he had hoped to inspire such dread in all heathens that New Mexico would be left in peace. But he was worried. His successor had arrived. This official spoke of summoning the Comanches to talk. Tomás Vélez Cachupín was back. [43] Again Vélez embraced Comanches, sat and smoked with them, and negotiated an exchange of prisoners. He condemned the arrogant Portillo, "who never wished to hear them speak directly to him." But even though don Tomás demonstrated again during his second term, 1762-1767, how Spaniards could reason with Comanches, the man who followed him, for one reason or another, was not up to it. Don Pedro Fermín de Mendinueta, whose eleven-year administration was the longest in New Mexico's history, and probably the bloodiest, never commanded the Comanches' respect the way Vélez Cachupín had. He was always on the defensive. [44]

Mendinueta Vacilla Not that Mendinueta wanted all-out war. He recognized that New Mexico was too weak, almost prostrate. Still, his superiors cried for blood, for the vindication of Spanish arms. Much of the time he spent trying to get the scattered Hispanos to come together in compact defensible communities, or placitas. Never able to win a great enough victory to dictate lasting peace, the governor vacillated as a matter of policy. Writing of the Comanches in 1771, he admitted as much.

If the viceroy had any better policy to suggest, Governor Mendinueta was ready to listen. [45]

Mostly War at Pecos For Pecos, traditional target of the Comanches, the now-peace-now-war regime of Fermín de Mendinueta meant mostly war. This was not war in the conventional sense, nor was there any reliable pattern to it. One time the attackers came in the dead of winter, hundreds strong, hurling themselves at the pueblo, and the next in spring or summer when only a dozen or so lay in ambush for workers in the fields, wood cutters, or hunters. The irregularity of this war, the not knowing, must have taken as great a psychological toll as it did physical. Like the serial stories filed by a war correspondent, Mendinueta's letters to the viceroy make up a chronicle. March 10, 1769: a Pecos reports fresh Comanche tracks some leagues from the pueblo. They lead in the opposite direction. Nevertheless, Alcalde mayor Tomás de Sena sends scouts and waits up at Pecos all night. When the sun rises next morning, the scouts still have not returned. Believing that the Comanches must have been after Apaches, the people let out their livestock without telling Sena.

The Pecos blamed this attack on their war captain, who had given the wrong location of the tracks. Mendinueta complained that he often received misinformation. No one saw the enemy, but everyone reported false alarms. [46] Early on a winter morning in December 1770, two Pecos venture out of their pueblo. A short distance down the trail some thirty Comanches jump them. It is over in an instant. The raiders also recapture sixteen horses stolen from them by Apaches who had come in close to Pecos. On April 5, 1771, forty Comanches assail the pueblo but are beaten off. The following month the alcalde mayor, probably Vicente Armijo, catches up with five Comanches rustling horses and kills all five with no casualty among the Indians who accompanied him. Again Comanches attack Pecos on September 5. Again they are repulsed. Later in the month, the governor sends the lieutenant of the Santa Fe presidio and two squads of soldiers. One squad escorts the Pecos to their fields to harvest and bring in their wheat. Despite the Comanches, who show themselves and shoot a few arrows from a distance, the soldiers, the Pecos, and their alcalde mayor fall back in good order with wheat and livestock. This time, the Comanches ride off. A month later they are back, an estimated five hundred strong. A smoke signal sent up by scouts alerts the Pecos and the squad of soldiers. The enemy, dismounted, tries to force one of the gates. They fail, losing five men killed and many wounded. Not always are the Pecos scouts so effective. Late that same fall, on November 25, five of them sally out of the pueblo at dawn right into an ambush. All die, along with an oxherd. [47] Eye for an Eye The worst war losses suffered by the Pecos during these years occurred in 1774. That spring, forty of them had left their pueblo to join a body of civilians and a soldier escort, bound perhaps on their annual trip to the salines. Because of the Pecos' "extreme want," Governor Mendinueta had granted them permission to hunt buffalo before joining up. But the Comanches took them off guard. Eleven were killed, one captured, and the rest fled, "losing their meager baggage." At three p.m. on August 15, the Pecos out working their milpas looked up to see a hundred Comanches bearing down on them. They scattered, but not in time. Seven men and two women died. Seven others were carried off. [48] This time the punitive expedition came through. The Comanches, reunited, were celebrating. "So many were the tents that they could not make out where they ended." Charging right into them, the Spaniards cut a bloody swath, then formed a square and held off the enemy all day before retiring in order that evening. An ever greater victory followed a month later. Mendinueta, availing himself of the New Mexicans' momentary high spirits, marshaled a force of six hundred soldiers, militia men, and Indians and sent them out under don Carlos Fernández, an aging but thoroughly proven campaigner. Taking another encampment by surprise, the Spanish force killed or captured "more than four hundred individuals," recovered a thousand horses and mules, and eagerly divided among them the tipis and other spoils of the Comanches. [49] Still, these triumphs did not end the war. In the months ahead, Comanches killed two Pecos cutting firewood, three sowing their fields, and one in a skirmish. In all, if the governor's figures are anywhere near accurate, between 1769 and 1775, some fifty Pecos must have died "a manos de los Comanches." No wonder Father Domínguez found them in 1776 cultivating only the fields within shouting distance of the pueblo. No wonder they had only a dozen sorry nags. No wonder they did not go to the river for a swim. [50]

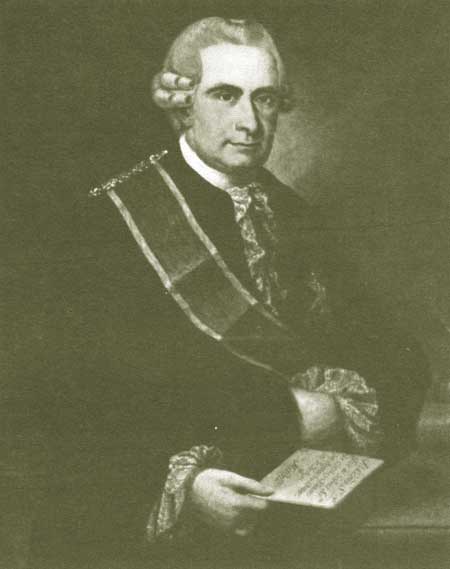

Anza Takes On the Comanches Already a hero, forty-two-year-old Lt. Col. Juan Bautista de Anza rode into Santa Fe late in 1778 with a confidence that bordered on cockiness. Unlike most of his predecessors, he already knew an Apache from a Pueblo. He was a frontiersman, born and reared in the presidios of Sonora. As swaggering as his position demanded, yet brave enough to close in hand-to-hand combat, Anza was a natural leader of fighting men. He had recently sat for a portrait in Mexico City. Feted at the viceroy's palace for opening the overland road from Sonora to Alta California, don Juan was still not too proud to embrace a Navajo or smoke with a Comanche. In that regard, he was every bit the equal of Vargas or Vélez Cachupín. And the time was right. He had just come from a series of meetings in Chihuahua with don Teodoro de Croix, first commandant general of the Provincias Internas. For more than a decade, reform-minded Spanish bureaucrats had been looking at the defense of the northern frontier as a whole. The Marqués de Rubí's inspection of 1766-1768, the resultant Reglamento of 1772 delineating the presidial cordon from the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of California, and the unified general campaigns of the redheaded Irish wild goose, Commandant Inspector Hugo O'Conor, had all followed in rapid succession.

Then, in 1776, don José de Gálvez, formerly the king's archreformer in New Spain, had become minister of the Indies. Within months, his vision of a northern jurisdiction independent of the viceroy and devoted to pacifying, developing, and defending New Spain's most exposed frontier was a reality. The six northern governors, from Texas to California, henceforth would answer to the commandant general. He would communicate directly with the king through Gálvez. Although the main object of the General Command was defense, the royal instructions as usual suggested a more noble purpose: "the conversion of the numerous heathen Indian tribes of northern North America." [51]

One of the decisions confirmed at the Chihuahua meetings would have a direct if belated effect on the Pecos. The Spaniards had resolved to seek peace and alliance with the Comanches against warring Apaches. There were precedents, particularly on the Texas frontier. Anza gave the project highest priority, setting aside temporarily the opening of a road to Sonora, the disrupting of the Gila Apache-Navajo alliance, and other pressing matters. Plainly, the Comanches, epitomized now by a fierce and implacable war leader named Cuerno Verde (Green Horn), were the kingdom's cruelest scourge. Before he parleyed, the new governor had first to show them who he was. That he did in 1779.

A Signal Victory over Comanches The muster at San Juan was set for mid-August, a time the Comanches might have expected to find them in their fields instead. In all, nearly six hundred men took part, none evidently from the overexposed pueblo of Pecos. Outfitting the dirt-poor militiamen and shaking the column down, Anza led them not by the traditional route east from Taos but north into Colorado and then east. Joined by two hundred Comanche-hating Utes and Apaches, to whom the governor explained his spoils policy of equal shares, the expedition pushed on to and across the Arkansas River. Somewhere north of present-day Pueblo they came upon a large body of Comanches setting up the pole frames of their tipis along Fountain Creek. The scene resembled a Catlin painting. The mountains towered to the west. Anxiously observing the Spaniards "drawn up in a form they had never before seen," the Comanches dropped everything, jumped on their horses and took off. After six or eight miles of pursuit across the grassy plain, the Spaniards and their Indian allies began to catch up. The Comanches wheeled around. Eighteen of the bravest died in the scattered melee. The women and children who ran to their fallen men were captured as were more than five hundred horses. Back at the half-made camp, the spoils were so plentiful that a hundred horses could not carry them all. Learning that this camp was to have been the rendezvous and site of a victory celebration upon the return from New Mexico of Cuerno Verde himself, Anza doubled back, in his words, "to see if fortune would grant me an encounter with him." It did. Somewhere in view of 12,334-foot Greenhorn Mountain, the bold Cuerno Verde, who knew of his people's recent defeat, had the temerity to attack six hundred men with only fifty. Judging from his own diary and the outcome, Anza's tactics were brilliant. Cutting Cuerno Verde and his staff off in an arroyo, he moved in for the kill. "There without other recourse they sprang to the ground and, entrenched behind their horses, made in this manner a defense as brave as it was glorious.... Cuerno Verde perished, with his first-born son, the heir to his command, four of his most famous captains, a medicine man who preached that he was immortal, and ten more." [52] The distinctive headdress of Cuerno Verde with its prominent green horn, and that of his second-in-command Jumping Eagle, were sent by a jubilant Anza to Commandant General Croix as trophies with a pledge to work for even "greater things now and in the future." Although his greatest achievement, the Comanche peace, would take another six years to consummate, this victory over Cuerno Verde had broadcast Anza's fame to every member of the Comanche nation. There would be no shame in coming to terms with this man. At Pecos, meanwhile, other died at their hands. [53] The Comanche Peace For reasons best known to themselves, the Comanches in 1785 began treating seriously of peace. Beyond the elimination of Cuerno Verde, reasons advanced by others include heavy losses in the smallpox epidemic of 1780-1781, military pressure by other tribes armed by the Spaniards on the east Texas frontier, a slow drift southward with corresponding diversion of raiding sphere from oft-plundered New Mexico to richer regions, Anza's refusal to admit their trade so long as they remained hostile, and the appeal of the titles and gifts and supplies offered by alliance. Perhaps the choice of Pecos as an access to Santa Fe and as the new focus of their trading was in part symbolic. Surely if a Pecos could embrace a Comanche, the lamb would lie down with the coyote. [54]

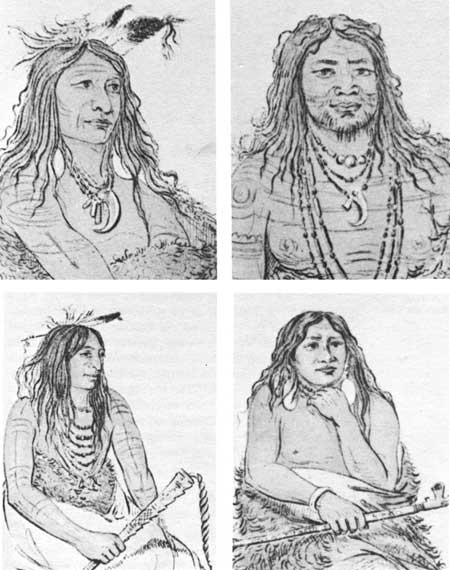

Anza made one thing clear. It was all or nothing. Each of the three major branches of the Comanche nation, the Jupe or Yupe (the people of the timber), the Yamparika (the root eaters), and the Cuchanec or Cuchantica (the buffalo eaters), had to concur. At a council on the Arkansas in November, attended by representatives of all but the snowbound northern Jupes and the easternmost Cuchanecs, they all did. It was resolved that Ecueracapa, leading chief of the Cuchanecs, speak for the others at Santa Fe. When José Chiquito, likely a genízaro, strayed from a party of Spanish buffalo hunters into Comanche hands, Ecueracapa made him and two Comanches his emissaries to the Spanish governor. He begged entrance though Pecos. Anza should warn the Jicarilla Apaches to let him pass. Feted in Santa Fe for four days, given horses and gifts for themselves and a horse and cap of fine scarlet for Ecueracapa, the emissaries could hardly wait to report back to their chief. Anza ordered them to take with them thirteen Pecos Indians and a Spaniard, evidently José Manuel Rojo. They departed Santa Fe on January 3, 1786. Meanwhile, a renegade bunch of Comanches tried to subvert the peace, killing Juan Sandoval, a Pecos, outside the pueblo. But diplomacy overcame. Ecueracapa so outdid himself to entertain the returning emissaries and their guests that they "never tired of elaborating on it when they got back to the province." On a cold day in February, the Pecos looked out on a rare sight, Comanches setting up their tipis in peace. A resplendent Ecueracapa rode on up to Santa Fe where Juan Bautista de Anza was waiting to receive him with honors due a visiting chief of state, with military escort, the municipal council turned out, pomp and an applauding crowd. Ecueracapa loved it. "His harangue of salutation and embrace of the governor on dismounting at the door of his residence exceeded ten minutes." Inside they talked of terms. A tense moment followed when Anza presented the Comanche chief and his staff to a Ute delegation, mortal enemies since mid-century. The very name "Comanche," applied to the plains nation by the Spaniards, derived from a Ute word for enemy, or "anyone who wants to fight me all the time." It had taken the governor hours of parleys to bring the Utes to the brink of reconciliation. "After several accusations and apologies by both parties this was achieved and formalized in their manner, chiefs and attendants exchanging their garments with their counterparts." After three days of conferences and festivities in Santa Fe, after Ecueracapa and the Ute chief had been regaled equally "to avoid jealousy which might prejudice their recent friendship," Anza led them and a colorful, polyglot concourse over the mountain to Pecos. There they would draw up the preliminary articles of peace. Conference at Pecos The Comanches who had camped before Pecos came out to meet the governor, "manifesting their great joy and delight." When he dismounted "at his own quarters," they crowded around him, some two hundred of them. "All, one by one, came up to embrace him with such excessive expressions of affection and respect that they were by no means appropriate to his rank and station." One of the governor's emissaries on the plains described how Comanches embraced him and rubbed their faces against his. Here Anza was at his best. [55]

Retiring to the lodging prepared for him, the governor took his midday meal in the company of the Comanche captains, some of whom wore such earthy names as Rotten Shoe, He Plays Dirty, and The Vermin. Anza's superior, Commandant General Jacobo Ugarte y Loyola, an old campaigner himself, painted a portrait in words of these Comanches after a delegation of them visited him in Chihuahua late the same year:

That afternoon, the business of making peace continued. Bare from the waist up, Tosapoy, who occupied third place in the Cuchanec order, delivered a moving harangue. As a token of good faith, on his knees he presented to Anza a Spaniard from Santa Fe, young Alejandro Martín, who had been a captive among them for eleven years. The governor now affirmed tentatively, pending the commandant general's approval, the five points presented in Santa Fe by Ecueracapa: 1) a new and lasting peace; 2) permission for the Comanches to move closer to New Mexico; 3) access to Santa Fe through Pecos and free trade at the latter place; 4) an alliance and redoubled war against the Apaches; and 5) acknowledgment before other Comanche leaders, since only Cuchanecs were then in attendance at Pecos. In compliance with the last point, the Spanish governor gave to Ecueracapa his own sword and banner and arranged that his staff of office be displayed to members of the tribe who were not present. The Comanches, in response, dug a hole in the dirt and refilled it, "performing various ceremonies suggesting that in so doing (as they said and as is customary among them) they were for their part also burying war." After many other Comanches had acknowledged the peace, either in Santa Fe or on the plains, Anza submitted the articles to Ugarte. The commandant general added some commentary and clarification but he approved the pact essentially as it was drafted at Pecos on February 28, 1786. [57] A Trade Fair Seals the Peace Next day in the new atmosphere of good feeling, Anza presided over a trade fair at Pecos. It was Ash Wednesday. Voluntarily "all the Comanche and Ute captains with the rest of the individuals of both nations present" accompanied the governor to receive the ashes at service. Afterwards, he published a decree designed to restrain the Hispanos' usual outrages during the trading and to set the rules. The old 1754 price list would govern, with two exceptions: trade knives and horses. Two knives would bring only one buffalo hide, and thirteen of the same, a single average horse. A decade earlier, describing what went on at Taos, Father Domínguez had written:

The infamous tricks were precisely what Anza wanted to avoid.

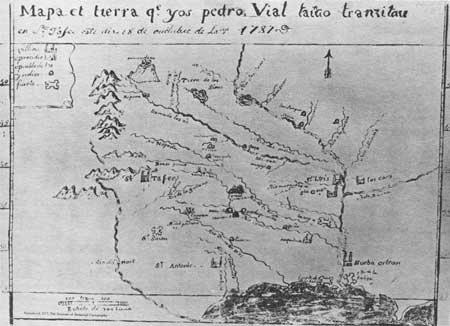

During the following months, Anza worked to secure Ecueracapa's preeminent position as captain general of the entire Comanche nation. And he succeeded. By April 1787, he had in hand a final treaty with all three branches. Ecueracapa had gone after Apaches and sent in tally sheets of his kills. His people had come again to trade at Pecos. Despite the replacement of Anza in 1787 and the death of Ecueracapa in 1793, despite the utter failure of the Jupes to settle down in the pueblo they asked the Spaniards to build for them on the Arkansas, despite troublesome hostilities of Utes, Navajos, and Jicarillas with Comanches, the alliance of Comanches and Spaniards embarked upon at Pecos in 1786 stood unbroken for a generation. [60] Plains Exploration In the fading light of afternoon, the Pecos made out riders approaching. As they drew closer, they could see that they were Comanches escorting a couple of Spaniards "with flag unfurled." Actually one was a Frenchman called Pedro Vial, a gunsmith and Indian trader now in the service of Spain. It was May 25, 1787. At the bidding of the governor of Texas, the explorer Vial had just made his way cross country clear from San Antonio. A couple of months later, old José Mares, long-time Spanish soldier at Santa Fe and scout, stopped over at Pecos. He was going to try it in reverse, from New Mexico to San Antono, taking with him Cristóbal de los Santos, who had been with Vial, and interpreter Alejandro Martín, the young man presented to Anza at the Pecos peace conference the year before. They also made it, by a shorter route, and returned. Vial followed in 1788-1789 with a trek from Santa Fe to Natchitoches to San Antonio and back, and in 1792-1793 to St. Louis round trip. Always they came and went through Pecos, New Mexico's eastern port of entry. As individual feats of exploration, these lonely voyages across the plains were prodigious. As moves on the international chessboard of North America, they were singularly puny. Spanish imperialists wanted to bind the Provincias Internas and Spanish Louisiana, to secure the middle of the continent from Englishmen out of Canada, Anglo-Americans shoving west, and conniving Frenchmen who wanted their American empire back. The explorations of Vial and "interpreter" Mares, in the words of Viceroy Revillagigedo, "have been and can be very important and conducive to counteract the dangerous designs of foreign powers." In the long run, they proved not very conducive at all. [61]

For a few short years, it looked as though Pecos might recover. The murderous assaults had ceased. The eastern gateway lay open. Trade picked up. "In the short time since my arrival," exulted Gov. Fernando de la Concha in 1787 three months after taking office, "seven fairs have been held at the pueblo of Taos, a very considerable one at that of Pecos, and another at Picurís, the most noteworthy since up to now none has taken place at this pueblo." [62] Nurturing Comanche Peace Concha was as careful of the Comanche peace as Anza had been. He treated with their delegations, provided maize as relief when drought temporarily drove the buffalo herds from their ranges, and regularly distributed gifts to them and the other allied tribes. Each spring when the caravan from Chihuahua pulled into Santa Fe, these heathen allies lined up for the dole. Bolts of bright cloth and quantities of hats, shoes, knives, mirrors, rope, strings of beads, coral, vermillion, indigo, bars of soap, cigarettes, and piloncillos, those hard-as-rock little cones of raw sugar, were a small enough price to pay. When treasury officials held up the four thousand pesos in 1790 for "extraordinary expenses of peace and war," Concha appropriated the funds allotted for the missionaries' allowances, assuring the commandant general in 1791 that the Franciscans had "gladly agreed to wait until this year." A bald forced loan, it clearly showed the governor's priorities. [63]