Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Dwindling Remnant If, as Josiah Gregg claimed, the last of the Pecos could be seen in the 1830s gazing off to the east, their thoughts were probably less bound up with the return of "Montezuma" than with the plains themselves, source of the wealth and the danger that once had made their pueblo the strongest of them all. Now as calicoes, hairpins, and hardware, the richest trade in the history of the plains, jolted by in the beds of Pittsburgh wagons, the Pecos had no part in it. They were too few now to be of any use—as converts to Christianity, as vassals or allies, as traders or carpenters. The priest came only when he had to, or not at all. The settlers in the valley encroached on the land of their fathers. Pecos was dying.

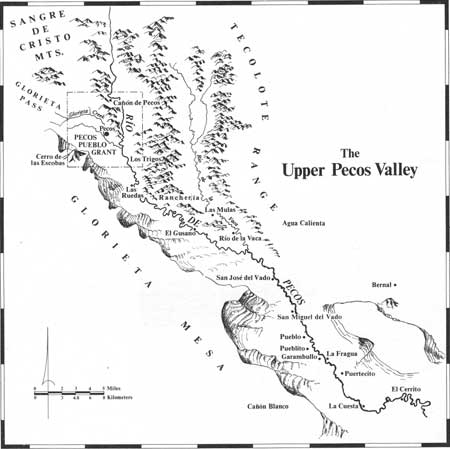

Settling San Miguel del Vado For the venerable pueblo at the eastern gateway, the turn of the century was a watershed. The New Mexico census of 1799 was the last to show Pecos with more Indians than non-Indians, 159 to 150. Five years before, in 1794, there had been no "españoles y castas" at all, no plaza or settlement of Hispanos dependent on the interim missionary of Pecos. With the petition of Lorenzo Márquez and his fifty-one land-poor compañeros, admitted by Gov. Fernando Chacó on November 25, 1794, the eastern pueblo's traditional isolation began to break down.

Their reasons for requesting a large settlement grant were the usual ones. "Although we all have some pieces of land in this villa [Santa Fe], they are not sufficient for our support, both because they are small and because of the great shortage of water and the crowd of people who make it impossible for all of us to enjoy its use." Since the Comanches by the mid-nineties appeared firmly committed to peace, New Mexicans could now contemplate the grass and good bottoms in the valley of the Río Pecos with an eye to possession. Márquez and company had already staked out a fine uninhabited site. Twenty-odd miles downriver southeast of Pecos pueblo, it lay at the place where the trail to the plains crossed the river, "where," according to the petition, "there is space enough not only for the fifty-one of us [fifty-two counting Márquez] who ask but also for as many in the province who are destitute." They described the boundaries of this new Eden simply: "in the north the Río de la Vaca [Cow Creek] from the place called La Ranchería to El Agua Caliente; in the south El Cañón Blanco; in the east La Cuesta and Los Cerritos de Bernal; and in the west the place commonly called El Gusano [South San Isidro]." Thirteen of the fifty-two men who applied were genízaros, those ransomed Indians and their descendants who lived as Hispanos, exactly twenty-five percent. Although more genízaros would move to the area later, the settlers themselves fostered the quarter-truth that his was "a genízaro settlement" in order to win concessions from church and state. Twenty-five of the fifty-two had firearms. All of them pledged as one "to enclose ourselves in a plaza well fortified with bulwarks and towers and to make every effort to lay in all the firearms and munitions we possibly can." Conditions of the Grant That sounded good to Governor Chacón. At his orders, don Antonio José Ortiz, alcalde mayor of Santa Fe, rode out next day to put the El Vado grantees in possession. First he read to them the conditions of the grant: 1) it was to be common, not for them alone but for future settlers as well; 2) they must be armed with firearms or bows and arrows, muster periodically, and all have converted to firearms at the end of two years—those who had not would be expelled; 3) they must build the plaza within the stipulated boundaries of the grant—"During the interim they should locate at the pueblo of Pecos, where there is sufficient lodging for the said fifty-two families;" 4) the alcalde of Pecos was "to set aside a small portion of these lands [presumably those of the pueblo] so that said families may plant them for themselves at their pleasure but without their children, heirs, or a substitute being able to inherit them;" 5) everyone must share in work on the plaza, irrigation ditches, and other projects in the common good. They agreed. "Therefore," wrote Alcalde Ortiz in the standard language of land grants,

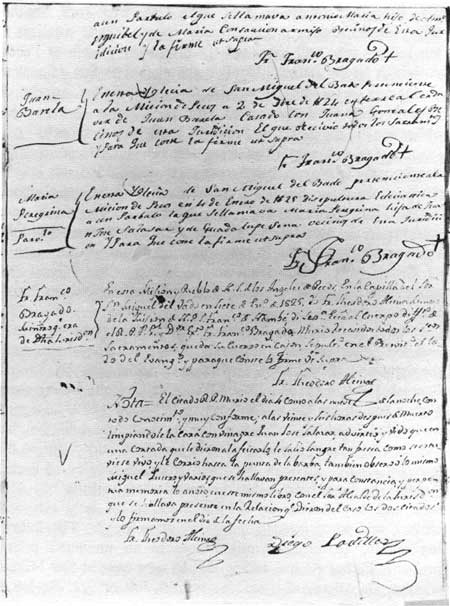

Evidently it took them some time to get themselves together. Although Lorenzo Márquez and Domingo Padilla, two of the El Vado grantees, or their Indian namesakes, showed up as early as the 1780s in the Pesos books as godfathers and marriage witnesses, no one identified as a settler of El Vado appeared until late 1798. Until they had homes up and fields planted, most of them preferred to leave their families in Santa Fe. Interestingly enough, the first entry for an El Vado resident, dated November 28, 1798, records the marriage of Juan de Dios Fernacute;ndez, "citizen (vecino) of El Vado and formerly an Indian of Pecos," to María, daughter of grantee Juan Armijo, "performed with the consent of their parents." A few Pecos, it would seem, did join the El Vado settlements, but very few. [2] Allotting Farm Lands By early 1803, the plaza, puesto, or población of San Miguel del Vado boasted fifty-eight heads of family. Having persevered the required five years, they had earned their legal stake in the community. In recognition, Governor Chacón "by verbal order" dispatched don Pedro Bautista Pino, who later gained a wider fame as New Mexico's delegate to the Spanish Cortés of 1810-1813. It was March, just before planting time. Don Pedro's job was to allot the available farm lands among all the families. "Because of the many bends of the river," measuring the total was a pain.

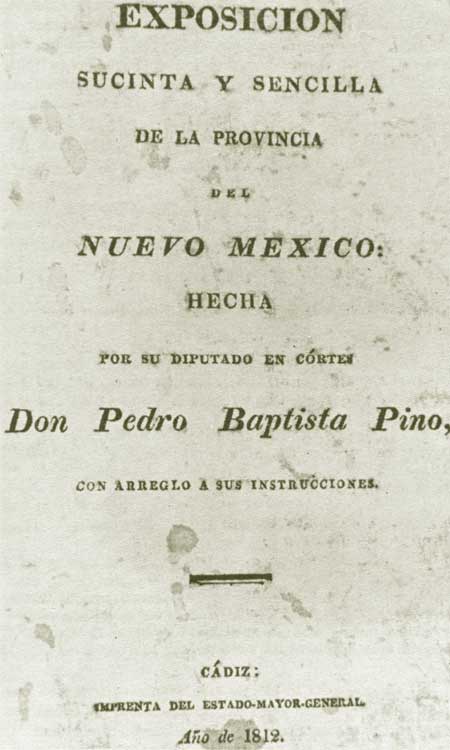

He began at the north. With the help of the interested parties he marked off the requisite number of parcels, trying as best he could to make them all equally desirable. Most were 50 or 65 varas wide, measured along the irrigation ditch, a few were 100 or 130 varas, and the largest 230. To match family and parcel, Pino had them draw lots. Then on a list next to the name of each, he entered the number of varas. One piece was reserved for the magistrate of the community, and a smaller surplus parcel to support three Masses annually for the souls in Purgatory. After the drawing, he marked the northern boundary at "a hill on the bank of the river above the mouth of the acequia that contains these lands," and in the south "the promontory of the hill of the pueblo and cañada they call Los Temporales." That left room for expansion southward. Finally, don Pedro called them all together and admonished them to put up promptly solid landmarks of rock. That would prevent disputes. None of them, he concluded, was free to sell or otherwise alienate his land for a period of ten years, beginning that day, March 12, 1803. After he had gone through the same routine two days later at the settlement of San José del Vado, three miles upstream from San Miguel, distributing farm land to forty-five men and two women, Pedro Bautista Pino made ready to ride back to Santa Fe. The settlers crowded around him. Nine years later he recalled the scene in his book.

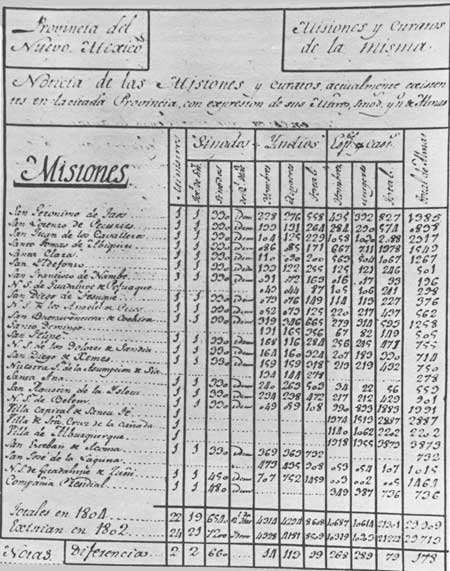

Spiritual Neglect of Pecos The presence of so many Spaniards and mixed-bloods making love, giving birth, and dying on the Río Pecos, at first far away downriver but still within the jurisdiction of the mission, should have meant closer attention to Pecos by the Franciscans. And it did for a time. Then, as the disparity widened, as the El Vado settlements propagated and Pecos shrunk further and further, the priest moved out to El Vado and visited the Pecos less often than when he had resided in Santa Fe. For the missionaries of New Mexico—whose priest-to-parishioner ratio had been thrown all out of proportion by the Hispano population spiral—overworked, undersupported, and often demoralized, it became a question of numbers. In 1794, there were 165 Pecos Indians and no settlers at El Vado; in 1820 only 58 Pecos, but by then 735 settlers. The friars responded accordingly. Baptisms, marriages, and burials of Pecos Indians and settlers of the El Vado district:

Whether justified by numbers or not, Christian nurture of Mission Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles at Pecos during this period can be summarized in one word—neglect. The same thing can of course be said of the colony as a whole. At the very end of 1799, when the authorities were again considering the creation of a diocese of New Mexico, as they did every so often, the province, including El Paso, was composed of nine districts with 23,648 Spaniards and mixed-bloods and 10,557 Indians, or a total population of 34,205. The villa of Santa Fe, with its 120-man presidial garrison and its population of 3,450 Spaniards, was the seat of a district that also included the missions of Tesuque and Pecos. In all, the province had twenty-six Indian missions. For the support of a missionary at each, the king provided the annual 330-peso allowance, except at Zuñi where 900 pesos were allotted for two. The few secular priests dispatched from Durango to serve the four villas did not often stay long in poor New Mexico. Seculars ministered at Santa Fe and El Paso, but the Franciscans were left to care for both Albuquerque and Santa Cruz de la Cañada. The missions were nine friars short. Pecos as usual was vacant.

Interim Ministers from Santa Fe During the 1790s, the assistant pastor at Santa Fe, a Castilian Spaniard named Buenaventura Merino, had been assigned to look after the Pecos. He came round every few months. He also saw to the Tewa pueblo of Tesuque, just north of Santa Fe. Born on February 24, 1745, at Villavicencio de los Caballeros in the diocese of León, the forty-year-old Merino had landed in America in 1785 with a group of recruits for the missionary college of San Fernando de México, supplier of Franciscans to Alta California. He had hated the rigorous routine at the college. After four and a half years of it, he threw in with the disillusioned Fray Severo Patero, just back from Spain's aborted Nootka Sound colony. Together they petitioned the viceroy for permission to serve in New Mexico. The college's superior, who pointed to the crying need for missionaries in California, chose to release them, and the two had shown up in Santa Fe in September of 1790. Reporting on his ministry in 1801, Father Merino put the total population of Pecos pueblo at 59 males and 64 females. There were 182 settlers downriver at San Miguel del Vado, 85 of them men and boys and 97 women and girls. Characterized by the friar as "very poor," both Hispanos and Indians grew maize, wheat, and a few vegetables in fields irrigated by the Río Pecos, but only enough to subsist. They ran only a few head of cattle and no sheep or goats "because the enemies don't let them increase." Filling out the rest of the questionnaire, Merino declared that in his district there were no industries or commerce worth mentioning, no bridges over the river, and no good timber for the royal navy. [6]

Merino's successor, Fray Diego Martínez Arellano, a discouraged Mexican veteran who began ministering at Pecos and El Vado in the spring of 1802, greeted his reassignment after two years as a blessing. Writing his last entry in the book of baptisms, he let his feelings show. He could not find the parents of the Pecos baby girl he had just baptized. The reason was plain. "All the Indians," noted Martínez, "live publicly in concubinage because the officials, both Spaniards and Indians, tolerate it. And the minister can do nothing to remedy it because they tell him he is being indiscreet." [7] Their next minister, one of the newly arrived peninsular Spaniards, stayed around longer but devoted almost all his time to El Vado. Thirty-five-year-old Fray Francisco Bragado y Rico, from the neigbborhood of tiny Villalonso and Benafarces in the diocese of Zamora, Castilla la Vieja, had "no degrees other than being a Christian, priest, and friar of Our Father St. Francis." [8] He appeared at Pecos in June 1804 and very soon took up the cause of the settlers. It was not right that "the genízaros" of the new settlement had been denied Mass and the word of God simply because they lived so far from Pecos over "a bad and very perilous road." They deserved a chapel of their own, where they could be baptized, married, and buried without an all-day journey. They had in fact already begun one by December of 1804 when Bragado petitioned the bishop of Durango for a license. "This settlement," he wrote, "is composed of one hundred and twenty families, all poor and unfortunate people with no greater resource for their subsistence than their own labor and no greater possessions than the little land with which Our Sovereign (God save him) has succored them." It worked. By the following spring, they had the license. [9]

Governor Chacó Damns the Friars On the last day of 1804, Governor Chacón filed a state-of-the-missions report. It stung worse than the knotted cords of the disciplinas, the scourge. According to him, the missionaries were gouging the poor citizenry who depended on them alone for the sacraments. They charged exorbitant fees, disregarding the schedules set by the distant bishops of Durango. If someone could not pay a baptismal or marriage fee, the friars set them to work. It was common on the death of a poor colonist, said Chacón, that the friar suddenly became the deceased's sole heir, while the legitimate heirs found themselves reduced to utter penury. If anyone thought the Franciscans confined their venal practices to Hispanos, the stiff-necked Chacón meant to set him straight. The Indians had to pay to celebrate their mission's patronal feast, or else it was cancelled. It was customary, too, every All Souls Day, November 2, after the harvests were in, for the Indians of all the pueblos to enter the churches laden with offerings of produce of every kind. These went to the friars. When an Indian died, his family paid the missionary for the funeral Mass in livestock if possible, or, despite the natives' legal exemption, in personal service, "especially the friar who treated them well." For years, Chacón alleged, some ministers had let the Indians sell off portions of the four leagues of land each pueblo enjoyed under the law, thus contributing further to their charges' privation.

Addressing himself to the Franciscans' spiritual care of the Pueblos, the governor dragged out all the old allegations. Few of the Indians confessed annually, waiting instead until moribund, when they did so only through an interpreter. None of the missionaries in 1804 had a knowledge of the native languages, "nor," claimed the governor, "do they exert the least effort or application to acquire it." For the most part, the Pueblos understood Spanish but preferred not to use it, especially the women. The friars left religious instruction to other Indians, the fiscales—a scandal in Chacón's book.

A Church for El Vado Father Bragado endured at Pecos almost six years. He saw the rowdy mixed-breed communities of San Miguel and San José del Vado almost double in size. Evidently work was progressing on the San Miguel church, but not without incident. Once in the summer of 1805 when Manuel Baca, interim deputy justice of the district, ordered Ignacio Durán, in charge at San José, to beat the drum for the people to come work on the church, not everyone assembled. Reyes Vigil and his sons refused. When Duran ordered them, Vigil told him that he could "eat shit, eat a bucket of shit!" Afterwards, at Vigil's corral, the two got into a name-calling, rock-throwing, hair-pulling brawl. Because only a part of the record survives, the outcome of the ensuing legal action is not known. [11]

As their priest, Bragado found himself very much involved in the lives of the El Vado settlers. Early in 1809, he and Teniente de justicia Manuel Baca appeared together before Custos José Benito Pereyro to forgive each other and to drop the proceedings they had entered into. They vowed not to rekindle this or past differences. When the custos informed Gov. José Manrique of the reconciliation, the governor warned that it was not genuine. All Baca wanted was to bring to his side the woman who had been the cause of the trouble. Father Bragado had better watch his step. [12] Whether or not the Baca affair hastened his departure, Bragado cleared out early in 1810, the moment a replacement was available. The custos transferred him to San Ildefonso and assigned in his place Fray Juan Bruno González, an untried Spaniard who had arrived in Santa Fe on February 26 and who found himself minister of Pecos and El Vado on March 12. Like his predecessors, he soon learned that the settlers were as unreliable as the Pecos when it came to notifying the Father that someone was dying. He stayed not quite one year. [13]

Rebellion in New Spain As Fray Juan Bruno ministered on the Río Pecos, he heard the ghastly news of 1810. Unless inured by the incredible plague of events that had rendered his homeland a satellite of the monster Napoleon, the Spanish Franciscan must have blanched. A mad diocesan priest drunk with the heady spirits of the French Revolution, one Miguel Hidalgo, had raised the cry of independence and liberty at a little town northwest of Mexico City. The rabble had risen. They killed and burned and looted in an orgiastic caste war that threatened briefly to envelope the entire heartland of New Spain. But because the rebels were ill organized and unsustained, royal forces had taken the offensive. Before Father González left Pecos, they had captured Hidalgo. He was to be shot.

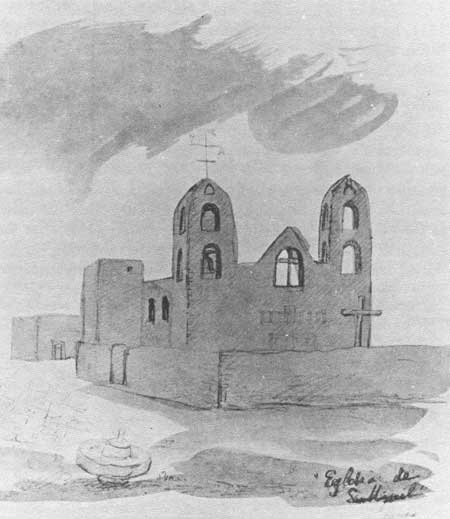

The Priest Moves to El Vado Twenty-seven-year-old Fray Manuel Antonio García del Valle, a native of Mexico City, did not stand on tradition. Granted, he had been appointed minister of the mission of Pecos, and it was still the cabecera, or seat of the "parish," but he saw no earthly reason for him to reside in a dying Indian pueblo when the large majority of his parishioners lived ten leagues or so downriver. After relieving González in March 1811, he baptized thirty-two infants for the settlers of El Vado before a Pecos Indian couple finally had a baby. That year the settlers at last finished the chapel of San Miguel del Vado. [14] Why should he not reside there?

To make his change of residence legitimate, Father García del Valle needed the approval of the see of Durango. The people of El Vado must send a petition. It was first-rate, a real propaganda piece. They chose José Cristóbal Guerrero, a genízaro of Comanche origin, to represent San Miguel and San José, two hundred and thirty heads of family "well instructed in the obligations of Christians." They made the most of the fact that Comanches, not really that many according to the books, were joining their communities and taking instruction for baptism. Not only did this swell their numbers, but it also cemented the peace between Comanches and Spaniards. "As a result," they predicted with chamber-of-commerce élan, "it is to be expected that within a few years these will be the most populous settlements in the province of New Mexico."

In sharp contrast stood the dying mission of Pecos. Only thirty families of Indians lived there "and of so little capacity that they received only the sacraments of baptism and matrimony." Fray Manuel, missionary at Pecos, had indicated to the settlers his willingness to move to El Vado. They requested therefore that he be allowed to do so, with the obligation of visiting Pecos with an escort once a month. Early in 1812, the diocese approved. For better or for worse, the Pecos had lost their resident minister for good. [15] Pino and the Spanish Constitution That same year in far-off Cádiz, capital of the resistance in French-occupied Spain, don Pedro Bautista Pino published for the benefit of his fellow delegates to the Cortés and the world at large an Exposición sucinta y sencilla de la provincia del Nuevo México. His goal was reform. Hoping to win for New Mexico the often-proposed diocese, he proclaimed the sorry state of the church in his province. All of New Mexico, with twenty-six Indian pueblos and one hundred and two Spanish communities, had only two secular priests and twenty-two Franciscans. Distances were great. As a consequence, many New Mexicans did without spiritual care. The absence of a bishop, moreover, had caused them, in Pino's words, to suffer "infinite harm." Not since 1760 had their primado pastor visited New Mexico. For half a century no one had been confirmed. They had forgotten that there was a bishop. Ecclesiastical discipline foundered. Many who needed a dispensation to marry, but who were too poor to travel to Durango to obtain one, lived and raised families in sin. It was a crime that a province producing nine to ten thousand pesos annually in tithes had not seen the face of its bishop in more than fifty years. "I, who am older," Pino confessed, "never knew how bishops dressed until I came to Cádiz." [16] He was convincing. The Cortés voted in favor of a diocese and a seminary college for New Mexico. On the Río Pecos a skeptical Father García del Valle took part in the excitement as the El Vado settlers elected their "parochial elector" under the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812, a thoroughly new experience. [17] But none of it came to anything. Napoleon let Ferdinand VII go. Once home on the Spanish throne, the king abolished the constitution, dissolved the Cortés, and nullified all its legislation. And that was that. As the people said, "Don Pedro Pino fue, don Pedro Pino vino." Enduring Comanche Peace For the most part the Comanches kept the peace. By the 1790s, it was habit. Even though the pueblo of Pecos declined visibly, even though more and more "comancheros" were taking the commerce of New Mexico out onto the plains, still the Comanches honored the tradition begun at the peace conference of 1786. They came to Pecos to trade, and they came to parley. When Tampisimanpe, the Eastern Comanche captain, reined up at Pecos in July 1797, he wanted to trade and parley. He wanted to see Governor Chacón confirm a "general" of the Comanche nation. It had been prearranged. The other Comanche captains had gathered. Next day at a solemn junta presided over by the Spanish governor, Canagüaip of the Cuchanticas received "a plurality of votes," whereupon Chacón recognized him in the king's name.

Before they departed, the Comanches presented to the governor two Spaniards, servants of a French trader abducted on the plains by unfriendly heathens. The governor sent them off to Chihuahua to see the commandant general. [18]

On occasion, Comanche leaders tried to put one over on the Spaniards. Chacón caught the Yamparika captain Guanicoruco at it in 1804. This Indian had traveled to Chihuahua, probably in the annual trade caravan, for an interview with Commandant General Nemesio Salcedo. He had several things on his mind. First, he was unhappy with interpreter Juan Cristóbal who neglected to carry the reports of the Comanches to Governor Chacón. He asked permission for a son of his, one José María who had received baptism at Chihuahua in 1803, to live at San Miguel del Vado and serve as interpreter there and at Pecos during the trading. He also requested license to hold the trade fairs at Pecos because, en route through the mountains from that pueblo to Santa Fe, their animals suffered and Apaches killed their women and children who followed along behind. Guarnicoruco had another son whom he believed should be named captain of the Yamparikas. Lastly, he volunteered to guide Spaniards to the Cerro Amarillo, fifteen days east of Pecos and El Vado, so that they could determine whether it was gold or some other metal. Salcedo, requesting that the governor keep him informed, passed these maters on for Chacón's attention. [19]

The New Mexico governor was frank. Guanicoruco was a liar. Interpreter Juan Cristóbal had not been assigned to the Yamparikas since Chacón took office. José María Gurulé was not a son of Guarnicoruco, rather a Skidi Pawnee genízaro who had once been a captive of the Comanches. Chacón had sent him to El Vado as Comanche interpreter with the first settlers. But because of Gurulé's unruly conduct, cheating, and horse thieving, the governor had removed him "at the petition of the entire nation" and put paid interpreter Alejandro Martín in his place. As for Guarnicoruco's request to trade at Pecos, that was absurd. "I have not heard," wrote Governor Chacón,

If Chacón tried to elevate Guarnicoruco's son, who was only fourteen or fifteen years old, he would lose the confidence of the rest of the nation. If this Indian knew where to find the Cerro Amarillo, let him bring in some samples. When Guarnicoruco showed up in Santa Fe, the Spanish governor reproached him for misleading the commandant general. Perhaps, the Indian replied, the interpreter had misunderstood what he was trying to say. [20]

The End of Prospector Castro The Spanish quest for a Cerro Amarillo or Cerro de Oro in Comanche territory, the enduring enmity of certain Apache bands, and a heightened United States threat across the plains all coincided early in 1804. A far-ranging prospector and buffalo hunter named Bernardo Castro had just ridden into Santa Fe from his second bootless excursion in search of the magic mountain. He claimed to have seen it once before, but only fleetingly by night. Frustrated by deep snows in his attempt to pack a couple of loads of meat up to the villa, Castro decided to go back to El Vado to get them. At the same time, he meant to check out a "very rich vein of silver" two or three leagues from there. Chacón had advised him to wait until it warmed up, but Castro replied that he did not know how to stand idle. Early in March, the teniente de justicia of Pecos and El Vado notified the governor of Castro's fate. A scouting party of twenty men under Diego Baca had picked up fresh tracks they reckoned were Apache, of seven afoot and two on horse back. They feared the horses might be Castro's. They were. That same day, Baca found the frozen bodies, Castro and José Antonio Rivera. He had them packed up to the mission of Pecos where Fray Diego Martínez Arellano gave them Christian burial, noting for the record that they had been "killed by Apaches while searching for the mine of the Río de Tecolote." The same day that Fray Diego put Castro's body in the ground, Diego Villalpando, whom Castro had left among the Comanches Orientales, appeared in Santa Fe. He had been beyond Natchitoches with a dozen Spaniards out of San Antonio. A few days after parting with these men, Villalpando had noted among the Comanches an abundance of loot. He surmised that the heathens had killed these Texans for their large herd of horses and mules. When the Comanches heard that the Spanish troops had ridden out of San Antonio to repel "some Englishmen or Americans," they headed for that villa. One Comanche who did not go for lack of a horse made known his desire to kill Villalpando. It was then that the New Mexican had made his escape. [21] The mention of Americans might well have caused Chacón to curse. The year was 1804. Thomas Jefferson had just stretched the United States constitution around sprawling, ill-defined Louisiana. Lewis and Clark were outfitting in St. Louis. From then on, right down to 1821, Spanish officials from San Antonio to Santa Fe would damn the Anglos, real or imagined, the likes of Zebulon Montgomery Pike, who came seducing the Plains Indians, filibustering, or just looking for commerce, honest or otherwise. While Comanches came and went, and once in a while an American or two, the real everyday enemy on the Río Pecos remained the Apache. In the mission book of burials, it was as if a line had been drawn at 1786. Before that, for a half-century, all deaths resulting from hostilities were attributed to Comanches, after that only to Apaches. The friars did not identify them as Jicarillas, Mescaleros, or others. But between 1790 and 1803, the entries for at least five Pecos Indians included the terse explanation "killed by Apaches." In 1804, it was Bernardo Castro and his companion, while six months later, four more El Vado settlers. Time and again settlers and Indians went after them, mustering sometimes at the pueblo and sometimes downriver at El Vado. For the most part, it was like chasing the wind. One seemingly typical militia force set out from San Miguel del Vado in mid-December 1808. They came from all over and included ten genízaros from Santa Fe and ten from San Miguel. For a total of 148 men there were 47 firearms and 263 rounds of ammunition. The rest carried only bow and arrows. [22] Lure of Trade on the Plains For the average mixed-blood or genízaro who drew a plot of ground at El Vado in 1803, it was not the prospect of a good year for maize or beans that excited him most, but rather the vision of hunting or trading on the plains. There could be profit in that. The case of Juan Luján, "Indian settler" who owned a 65-vara parcel, was probably not unique. He had walked to the Río Tesuque to see if he could talk Bartolo Benavides, a retired soldier, into going halves with him on an animal to use for buffalo hunting. He failed. On the way home, as chance would have it, he came upon a horse strolling unattended along the road toward Tesuque, or so he later claimed. Since a dog had just bitten him and walking was painful, Luján caught the horse and rode back to El Vado. The Tesuques came looking and charged him with theft. He said he was going to return the animal. For his error Juan Luján spent a month at labor on public works. [23] Near Rebellion in New Mexico Lt. Col. Joaquín del Real Alencaster, governor from 1805 to 1808, very nearly lost New Mexico, not to Apaches or Anglos, but to the people themselves. Times were hectic, to be sure. Competition for the loyalty of the Plains tribes quickened. Unwelcome American traders and explorers kept showing up in Santa Fe. Whether he was following orders or not, Real Alencaster's rude attempt to curtail the irregular plains traffic out of the province almost caused a rebellion.

At San Miguel on the Río Pecos, don Felipe Sandoval called a meeting, ostensibly to raise funds for the feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Juan Antonio Alarí, teniente de justicia of the Pecos-El Vado subdistrict, accused by the people of being a tyrannical bully for the governor, spied on the meeting. He was right. The Virgin was only a cover.

Sandoval was urging the people of San Miguel and San José to ignore the repressive measures of the governor and his henchmen. They should go to the Comanches and trade as usual. Just let the bastards try and stop them. The people of La Cañada and the Río Arriba were with them. At that, "with a garrote and clubs," Alarí broke up the meeting, and arrested Sandoval. When it was learned that Sandoval and José García de la Mora, "defender" of the people of the Río Arriba, had been hauled before the governor, a mob from the north started for the capital. Only when they had been given assurance that neither Sandoval nor García was in jail did they turn back. From testimony taken in Santa Fe, a number of additional grievances emerged: the limit on what New Mexicans could take in the annual caravan to Chihuahua, the prohibition against selling sheep to the Navajos, the collection of grain from the poor citizens of the Río Arriba to feed the Santa Fe garrison. When Real Alencaster sent the proceedings off to the commandant general, he included charges of sedition against Felipe Sandoval. This time nothing had come of it. In 1837, the mob would behead an unpopular New Mexico governor. [24] Don Alberto Maynez, who took over from Real Alencaster in 1808, was at pains to let the people of New Mexico know that they were at liberty to trade with the heathen nations and also with Nueva Vizcaya. All they needed was government approval and passports, these only to make certain the number of armed men per trading party was sufficient. Felipe Sandoval was vindicated. By 1814, he served as municipal councilman in Santa Fe and as protector of New Mexico's Indians. The settlers on the Río Pecos, with or without government sanction, kept on hunting and trading among the Comanches, enjoying "the best relations with that heathen nation . . . calm and at peace as always." [25] Maintaining the Comanche Dole Still, the New Mexicans were no fools. They knew that the only things that kept the Comanche "barbarians" at peace were trade and gifts. They knew that while they bartered cloth, hunting knives, and beads for horses and mules with one band, other Comanches were stealing more in Texas, Coahuila, or Nueva Vizcaya. When the Comanche general Soguara arrived in the fall of 1818 with "more than a thousand" of his people to trade, don Facundo Melgares, New Mexico's fat but singularly astute and energetic governor, gave out gifts until his warehouse was almost bare. He begged the commandant general to send more, posthaste. [26] Exactly a year later, Manuel Antonio Rivera, a plains guide from San Miguel del Vado who had spent the summer of 1819 among the Comanches, testified in Santa Fe that General Vicente was en route to see Melgares with news that "many Anglo-Americans were coming to attack this province." Vicente wanted to assure the Spanish governor "that the Comanches and he were prepared to fight the Americans because they advance taking Comanche horse herds and captives and because the Spaniards of New Mexico are their friends and the lord governor their tata [dad]" [27] Just how deep the Comanches' friendship ran was evident in August 1821 when Tata Melgares' gifts played out. Much of the viceroyalty had already pronounced for Agustín de Iturbide and independence. There was fighting elsewhere. Commandant General Alejo García Conde, who embraced independence that very month, could spare nothing for gratification of allied tribes. As the disgruntled Comanches rode back from Sante Fe through the El Vado district, they took out their frustrations en route, killing livestock, sacking several houses, stealing, and raping two women. "So as not to upset the peace" the settlers did not stand up to them. But they were furious. These outrages, protested Manuel Durán of El Vado, were the result of having cut off the customary Comanche dole. Did the governor recognize the implications? "This could be the cause of our losing their fidelity to the alliance we have with them." He begged Melgares to solicit contributions for an emergency fund. The governor agreed. He knew full well that all the province's heathen allies might rebel if not supplied the usual gifts. Circulating the El Vado plea, he urged the other districts to forward whatever they could to gratify the barbarians "and escape desolation and death." [28]

There were tense moments, to be sure, but the Comanches never did go on the offensive against New Mexico the way they had before 1786. The tradition of trade and forbearing intercourse prevailed. Never was the 1812 prediction of El Vado promoters realized, never did great numbers of Comanches come to live as Christians on the Río Pecos. But some did, and their names are scattered through the parish records.

That Indians of Pecos pueblo and Comanches continued to come in frequent contact, during "fairs" and on the plains, is beyond question, and perhaps, as one early anthropologist said, many Pecos "spoke Comanche as well as their own tongue." It seems doubtful, however, based on the same church records, that "there was much Comanche blood in the tribe." [29] As far as Pecos and Comanches were concerned, the hachet buried in 1786 stayed buried. But that did not always mean, literally, that they lay down together. The Pecos Pueblo League As they passed back and forth on the dirt track from Santa Fe to El Vado, breaking their journey at Pecos, more than a few Hispanos noted good land along the river, land that the Indians of the dying pueblo were not cultivating, vacant land ripe for the taking. In 1813, the year after Father García del Valle had moved down to San Miguel, an enterprising trio of "Spaniards and citizens of Santa Fe," by name Francisco Trujillo, Bartolomé Márquez, and Diego Padilla, requested "several pieces of land, unappropriated, untilled, and unimproved at the place called Las Ruedas, located in the environs of the pueblo of Pecos." Once the site of a prehistoric Pecos satellite community, Las Ruedas lay about four miles downriver from the pueblo, near present-day Rowe. Their ownership of such lands, the promoters averred, would in no way prejudice the settlers at San Miguel. Neither would it encroach in the direction of Pecos on "the boundaries of the league (which is ordered set aside for every Indian pueblo), not by far." [30] The famous "pueblo league" was a legal fiction. Before the eighteenth century, the Pueblo Indians seem to have been entitled under Spanish law to whatever lands they habitually occupied or used. Sometime after 1700, however, there evolved the doctrine of a given league, a sort of recognized minimum right of the Pueblos. In the case of Pecos, it was a minimum indeed, one eventually imposed by the growing Hispano presence and the pueblo's decline. In Spanish law, current use was the key. No matter that the Pecos had farmed or otherwise used more land historically, they were no longer using it in the nineteenth century. Measured one league, or 5,000 varas, in each of the cardinal directions from the cross in the mission cemetery, the standard "pueblo grant" thus contained four square leagues, roughly twenty-seven square miles, or more than 17,350 acres.

The only extant Spanish land title to Pecos pueblo is a clumsy forgery. One of the so-called Cruzate grants, allegedly made to eleven different pueblos in 1689, it was apparently part of a large-scale nineteenth-century hoax. Nevertheless, the description of the Pecos "grant" was accurate: "to the north one league, and to the east one league, and to the west one league, and to the south one league, and these four lines measured from the four corners of the pueblo leaving aside the church which is to the south of the pueblo." [31] So long as the Pecos had no neighbors, there was no reason for them to go out and measure their grant on the ground. After the Trujillo-Márquez-Padilla petition of 1813, there was every reason. But since that petition, forwarded by Gov. José Manrique to the commandant general, got lost in the bureaucracy, the earliest recorded measurement of the Pecos league took place in August of 1814. A Land Grant to the North Juan de Dios Peña, retired ensign of the Santa Fe garrison, and two companions were bidding for a grant just north of Pecos on both banks of the river. A settlement there, the would-be grantees declared, "will serve as a defensive outpost against the enemy Apaches and other barbarians." By order of Governor Manrique and commission of Santa Fe's constitutional alcaldes, Protector de indios Felipe Sandoval went to Pecos and in the company of Peña and local Alcalde Juan Antonio Anaya "we proceeded to measure to the satisfaction of the native principal men of the pueblo the league which from time immemorial His Majesty (God save him) has granted them to the four points of the hemisphere." On this occasion they did not say where they began the measurement. [32] For some reason—probably related to the restoration of Ferdinand VII and the reversal of reforms by the Cortés— Peña's 1814 petition was not acted upon. The following year, after there had been a change of governors, he tried again and was successful. Sometimes called the Cañón de Pecos, or the Cañón de San Antonio del Río Pecos, this, or a part of it, eventually became the Alexander Valle grant. Assured by Felipe Sandoval that "said site is independent of the league and farm land of the natives of that pueblo, at a normal distance, and very much separated from the property of said pueblo," Gov. Alberto Maynez sent Santa Fe Alcalde mayor Matías Ortiz out to put Peña in possession. "Beginning at the cross in the cemetery," said Ortiz, "I measured the league upriver and, having completed in full the Indians' league, in the surplus I took don Juan de Dios by the hand" and went through the usual routine. By starting at the cemetery cross, well south of the pueblo itself, Ortiz had lopped off just that much good irrigable land to the north. [33] Dispute at North Boundary The legal battle began in 1818. Juan de Aguilar of Santa Fe, one of Peña's two companions, believed that he had been defrauded. Three years before, he claimed, he had duly acquired a piece of land "in the place known as the surplus of Pecos." Later, the Pecos Indians had protested and called for a new measurement. The alcalde of El Vado, don Vicente Villanueva, complied. In so doing, Aguilar contended, he had deviated from established practice in two regards. First, he had begun from "the edge of the pueblo" instead of the cemetery cross, and second he had used a one hundred-vara measuring cord instead of the standard fifty-vara cord. "As a result several properties have been prejudiced." Aguilar begged Gov. Facundo Melgares to address himself to these two points.

Responding the same day to an order from the governor, Alcalde Villanueva defended his measurement. He had indeed used a one hundred-vara cord. To have used a shorter one, he alleged, would have been prejudicial to the Indians because of the irregular, broken terrain. He had wet the cord and stretched it to get the kinks out and then staked it taut. Aguilar and his sons had stretched it again until it broke. With them and "the other settlers of the rancho" looking on, Villanueva had measured one hundred varas on the repaired cord "to every one's satisfaction," shouting out the count as he went. That "several properties" had been prejudiced was a lie, said Villanueva, only Aguilar's. Actually one other property lay even farther inside the northern boundary of the Pecos league, but the owner, who did not want it, had died and his heirs wanted it even less. Villanueva had made a couple of other measurements for the settlers with the cooperation of the Pecos. As for his point of origin, the alcalde explained it in these words.

If the governor took any action, the record of it has long been separated from Aguilar's challenge and Villanueva's response. The precedent, however, was set. [34] A Land Grant to the South Meantime, Trujillo, Padilla, and Márquez had persisted. Submitting a new petition dated May 26, 1814, they asked this time for

The area known as Los Trigos, which gave name to the grant, pressed even closer to Pecos than Las Ruedas, extending from the latter to the present headquarters of the Forked Lightning Ranch. Eight or ten miles downriver, El Gusano, today's South San Isidro, was the western boundary call of the San Miguel del Vado grant and later the focus of a bitter boundary dispute. Governor Manrique, observing the letter of prevailing reform legislation, had passed the petition on to the Santa Fe municipal council for its approval. Convinced that the grant would not encroach on the prior rights of Pecos Indians or El Vado settlers, the council at its meeting of July 30, 1814, recommended that Trujillo and companions be put in possession "whenever it is convenient." But then word of the king's restoration reached Santa Fe. Trujillo and company waited another year. On June 22, 1815, Governor Maynez had set them straight. They could pasture their stock on the vacant lands that lay between Pecos and El Vado, but, if there were space enough, so could any other citizen. Only such lands as they might cultivate and fence, as well as the lots for their houses and corrals, would be covered by royal grant. That, years later, set the lawyers dancing an intricate step. Moreover, to make certain the Pecos league was being observed in full, the governor sent Matías Ortiz and the petitioners to Pecos. There on October 20, 1815, said Ortiz, "I measured a fifty-vara cord and handed it over to the Pecos Indians so that they might measure it to their satisfaction. Then, having measured [on the ground] a hundred cord-lengths to their entire satisfaction, I set their boundary." [35] Now, both downriver and up, the land was taken. Although there was a lag between the issuance of these grants and their actual settlement, the Pecos soon had next door neighbors.

The Onslaught of Settlers Evidently Santa Fe promoter Esteban Baca, who rounded up sixteen willing derelicts in 1821, would have moved right into the pueblo. In his application for a settlement grant, which seems to have been lost in the independence shuffle, don Esteban did not mince words. He understood that there were now only eight or ten Pecos Indian families left, and all that land going to waste. Their church was falling down. Their minister had abandoned them. Because they were so few, "and having no title," the Pecos were plainly in peril. Besides, the king wanted vacant lands peopled and planted. Therefore, reasoned Baca, his people, "leaving to the Indians whatever land they can cultivate," would move in, reverse the downward population trend, rebuild the church, and bring in a minister. It was, if nothing else, a very good try. [36] The real onslaught began in 1825. That year Gov. Bartolomé Baca and the Diputación Provincial, New Mexico's token legislature under the Mexican constitution of 1824, in effect threw open the Pecos league. A typical grant of lands allegedly uncultivated by the Pecos for many years went to the illiterate Rafael Benavides and several companions. Its boundaries were "to the east the little springs that are on this side of the Río de la Vaca [Cow Creek], to the west the river, to the north the trail that comes down from Tecolote, and to the south the boundary of Diego Padilla [one of the Los Trigos grantees]." The word spread. One Luis Benavides pleaded in March 1825, the same month he retired from military service, for a "small property in the surplus land of the natives of Pecos to sow a few maize plants and some wheat" for his large family and "relief from so many miseries." [37]

With or without grants, they came. Almost overnight dozens of families settled "the Cañón de Pecos." Beginning with the baptisms of two male Roybal infants in the mission church, April 16, 1825, mention of Hispanos from the Cañón de Pecos became more and more frequent. This in fact was the beginning of the present-day village of Pecos. By the early 1830s, the priest at San Miguel del Vado was listing settlers merely "from Pecos," and in May of 1834, he buried a boy "in the chapel of Pecos." Plainly they were there to stay. [38] The Pecos Fight Back The few remaining Indians of the pueblo did not surrender to encroachment without a fight. When proceedings in their favor, supposedly sent by the governor in 1825 to the Mexican congress, "went astray," they tried again the following year. Alcalde Rafael Aguilar, his lieutenant Juan Domingo Vigil, and "General" José Manuel Armenta, all Pecos Indians, appealed to the Diputación to halt the unlawful alienation of their lands. Some recipients of these grants were speculating. Without having acquired any legal rights to the land or having occupied it the required five years, they had begun selling it off. Others had already planted at the insistence of don Juan Vigil, one of the grantees with Rafael Benavides. "It is not nor has it been our desire," the Pecos insisted, "that they give them our lands." What the Indians had not planted, they used as pasture for their livestock. Had they no rights as citizens under God and the nation? "Well we know that since the conquest we have earned more merits than all the pueblos of this province." If grants were to be made, they should be of land truly vacant, "as it is at Lo de Mora, at Las Calandrias, at El Coyote, at El Sapell&oaucte;, on the plains of the lower Río Pecos, as it is on the lower Río Salado and the R&iaucdte;o Colorado [the Canadian]." Those were truly lands without owners—a fact certain Apaches and Comanches would surely have challenged. [39] At least they had bought time. None of the settlers, came the word from Santa Fe, could sell or otherwise alienate Pecos lands until the government resolved the matter. When Gov. Antonio Narbona finally had in hand the information he had requested from the constitutional alcalde of El Vado, he reported to the Mexican minister of domestic and foreign affairs. Narbona was bluntly on the side of the settlers.

The lands in question at Pecos amounted to "8,459 varas" on both sides of the river, "abandoned," in the governor's words, "many years back." The forty-one settlers involved had had to clear what they had been given. These lands, according to the governor, lay farther than half a league from the pueblo. The Indians, no more than nine families, not even forty persons, still possessed a full league in the other directions, largely unattended and unworked. No wonder these Indians were the poorest people in New Mexico. They had always refused to mingle with the Hispanos, hence "their barbarous state." Narbona had little sympathy for them. His suggestion was to break up the Pueblo communes, to give each Indian individual property rights. That way the Indians themselves would progress toward civilization, and lands that lay barren would be brought under cultivation. Otherwise, the Pueblos would remain "mere slaves to their ancient customs," as Narbona put it.

Narbona's rhetoric solved nothing. His ebullient successor, Manuel Armijo, inherited the problem. The settlers divided into factions. In March 1829, thirty-one individuals, who were "settled in the Cañón de Pecos," signed or put their x's on a document at the "Ciénaga de Pecos" reiterating their opposition to others who had been granted land in that area. There simply was not enough to go around. That same month, the Pecos protested again. Rafael Aguilar and José Cota, representing the pueblo, beseeched the Mexican governor to hear them. It had now been five years since their lands had been invaded by settlers. Apparently the governor had ordered that these intruders be given final title. Still, the Pecos begged him to consider

It was a good question, good enough that a commission was named to consider it. Carefully weighing the petition of the Pecos along with other documents bearing on the case, the commission came up with a surprisingly unequivocal two-point answer, which the Diputación enacted.

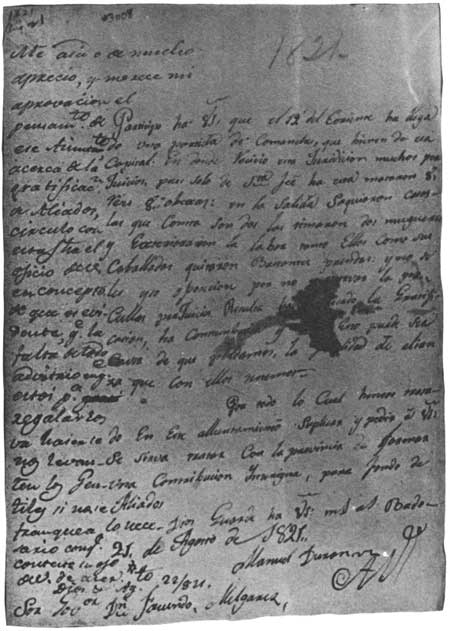

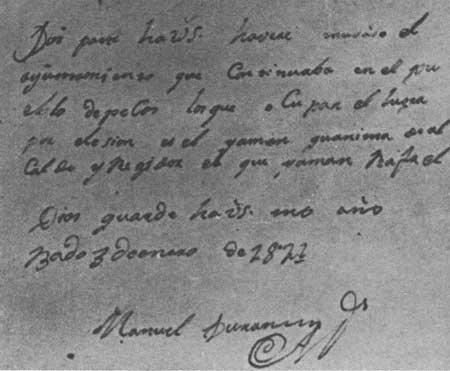

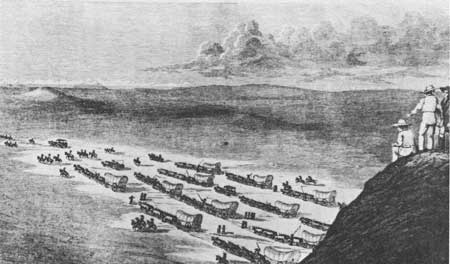

Now it was the affected settlers' turn to cry violent despoilment. The case went to court. [43] Whatever the details, the decision did not adversely effect the lineal descent of the full Pecos league in the courts. Whether the settlers actually got off the pueblo's land is another question. From the El Vado church records and the subsequent settlement pattern, it is plain that they did not. When the pitiful remnant of Cicuye, the eastern fortress-pueblo, finally resolved to abandon the place, the persistent invasion of their lands beginning in 1825 must surely have been a factor. [44] Santa Fe Trade Late in 1818, after an absence of more than eight years, the aging fifty-year-old Fray Francisco Bragado returned to the Pecos Valley. He settled in at San Miguel del Vado. When the spirit moved him, which was not very often if the church records are any indication, he climbed on a mule or horse and rode with an escort to the mission of Pecos. More often than not, the Pecos who cared came to him. While he sat by a fire or in the shade of a portal at San Miguel, Father Bragado rarely lacked topics to chew over with his cronies. Times were changing at a dizzy pace. He could talk elections. Under the reimposed Spanish constitution, which seemed a cruel mockery to traditional monarchists, even the few Indians at Pecos elected a municipal government in January 1821, Quanima as alcalde and Rafael as the one council-man. [45] Then there was all the talk of Mexican independence. As a peninsular Spaniard, but a rather down-to-earth sort, the Franciscan must have had mixed feelings about that. From his vantage at El Vado, he witnessed the opening of the Santa Fe trade, a business that would reorient New Mexico's economy and pave the trail for the United States Army a quarter-century later. Enterprising, semi-literate "Captain" William Becknell was the first. Gambling on a cordial reception by Governor Melgares, he and a company of twenty to thirty men had set out from Missouri with their merchandise lashed aboard pack animals. In mid-November of 1821, they pulled into San Miguel. Up in Santa Fe they made a killing, commercially speaking. The next year they were back with wagons. In 1825, the year Father Bragado died, goods estimated at $65,000 passed over the Río Pecos ford. San Miguel was the port of entry, the ancient pueblo of the Pecos no more than a curious relic up the trail a ways. [46]

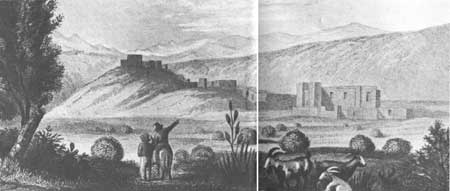

The hapless Thomas James and party, forced by Comanches on the plains to hand over much of their merchandise as a guarantee of safe passage, had crossed the ford at San Miguel only two weeks after Becknell. James was the earliest Anglo-American visitor to describe in detail the pueblo of Pecos, or the Fort as he called it. Despite the quarter-century that elapsed between his overnight stay on November 30-December 1, 1821, and the publication of his Three Years among the Indians and Mexicans in 1846, the word picture he painted was essentially accurate. He mentioned nothing of Montezuma, a perpetual fire, or a huge voracious snake. Leaving San Miguel, which James described as "an old Spanish town of about a hundred houses, a large church, and two miserably constructed flour mills," the Missourians fell in with a company of New Mexicans.

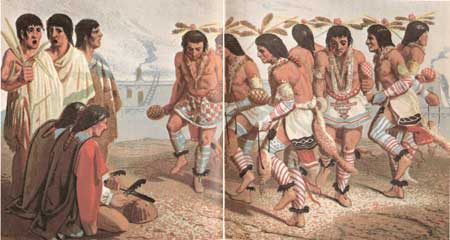

Mexican Independence On Epiphany, Sunday, January 6, 1822, in Santa Fe the wide-eyed, waspish Thomas James witnessed New Mexico's celebration of Mexican independence. To hear him tell it, he was indispensable, erecting the seventy-foot liberty pole and running up the first flag. But his heart was not in it. The revelry scandalized him, or so he said. "No Italian carnival," he reckoned, "ever exceeded this celebration in thoughtlessness, vice and licentiousness of every description." An unforgettable day, Gov. Facundo Melgares called it in his official report. Surely some orator likened the coming of the Three Kings to the coming of the Three Guarantees—Independence, Religion, and Union. There were salvos, processions and pageants, and, as on most public occasions, Indian dances in the plaza. James, who wrote in retrospect during a time of intense anti-Mexican feeling, never tired of comparing the low-life Hispanos of New Mexico to the sober and industrious Pueblo Indians. He admired the people of San Felipe who "danced very gracefully upon the public square to the sound of a drum and the singing of the older members of their band" during the second day's festivities. "About the same time," he remembered,

The Last Franciscans Francisco Bragado y Rico, who in 1805 had secured a license from the bishop for a chapel at San Miguel del Vado, twenty years later was laid to rest in that chapel in a box on the gospel side of the sanctuary. He died on January 4, 1825, "fully conscious and well disposed," consoled by Fray Teodoro de Alcina de la Boada of Nambé. His passing was attended by a sign, which Father Alcina dutifully recorded.

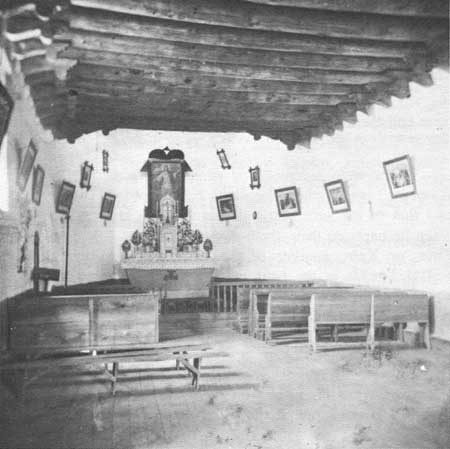

Bragado's successor, Fray Juan Caballero Toril, another fifty-year-old native of Spain, made every effort to minister to the Indians who still inhabited the crumbling pueblo of Pecos. Although he no longer identified the chapel at San Miguel as "belonging to the mission of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de Pecos" after December 1825, Caballero took seriously his obligation to say Mass at Pecos at least once a month. It was not easy. The friar and Alcalde Gregorio Vigil nearly came to blows over the escort required for a safe trip to the mission. When Caballero complained to Governor Narbona during Holy Week in 1827, the governor addressed a stern warning to the alcalde. If Vigil did not see to an escort for the minister so that he could carry the sacraments to the natives of Pecos, perhaps the priest would abandon San Miguel and move back up to the mission. Father Caballero had his escort that same day. [49] Late in 1827, amid rumors of Spanish plans to invade and reconquer Mexico, the Mexican national congress decreed the expulsion of peninsular Spaniards from the republic. Several Spanish Franciscans left New Mexico as a result, among them Father Caballero. On the last day of February 1828, he signed a detailed inventory of everything he had found in the San Miguel chapel and sacristy, all that had been added during his ministry, as well as items borrowed from the mission of Pecos. Among the latter were a broken metal cross, a little box with lock and key containing the silver cruets of holy oils and chrism, and some molds for making altar breads. The following month, Governor Armijo wrote to an unnamed priest, probably Father Alcina, telling him to take over at San Miguel whether Caballero, who said he was ill, left or not. He left. [50]

During the remainder of 1828, Fray Teodoro Alcina alternated at San Miguel with Fray José de Castro. They were both European Spaniards, but too old and too much needed in priest-poor New Mexico for expulsion. Alcina, from Palafox in Gerona, had spent thirty-five of his sixty-two years in New Mexico. Castro would bury him at Santa Cruz de la Cañada in 1834. Only a year younger, Castro himself, a native of San Salvador del Cristinado in Galicia, was dead by late 1840. [51] The books of baptisms, marriages, and burials assigned to Mission Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de Pecos, which, like its missionaries themselves, had spent most of the previous century at Santa Fe or El Vado, ended in 1829. On June 2, 1828, Father Castro had performed the last recorded baptism of an Indian by a Franciscan at Pecos, for eight-day-old José Manuel, son of Rafael and Paula Aguilar. The following November, the dutiful Father Alcina visited the mission and baptized the infant son of settlers from the Cañón de Pecos. His burial entry at San Miguel on December 3 was the last by a friar. On January 1, 1829, don Juan Felipe Ortiz, diocesan priest from Santa Fe, took over. After better than two centuries the Franciscan ministry on the Río Pecos had come to a close. [52] In 1833, when the first bishop, the stern and tireless José Antonio Laureano de Zubiría y Escalante, actually came to San Miguel del Vado on a visitation, he was appalled. Because of an acute shortage of ministers, the secular priest of Santa Fe was riding out on circuit. The fabric was a mess, the accounts hopeless, and the church "utterly deprived." Lord have mercy. "With much grief and sorrow," the bishop's secretary noted in the book of baptisms, "he has observed that this parish church lacks even the most essential things for the celebration of the divine mysteries." He did not even mention the mission of Pecos. [53]

Hanging On They were still there, thirty or forty of them, like the ghostly survivors of a science fiction tragedy, haunting the ruins that once had housed their civilization. Digging there in the twentieth century, archaeologists could tell how it had gone, "the bunching up or huddling . . . the long, slow decay eating its way northward in both the South Pueblo and the Quadrangle." [54] They could not survive much longer. Just as well. The Hispanos wanted their lands so much that they had threatened in the previous decade to remove them bodily and scatter them among the other pueblos. Now they were too few to cope. Still the old woes persisted—plains raiders, emigration, even, if the fantastic story spun for a late nineteenth-century romantic has any basis in fact, internal dissension, [55] and of course disease. Despite the introduction of vaccination against smallpox in New Mexico as early as 1805, when inoculated children were used as living vials to transport the vaccine, the dread disease, sometimes in league with other killers, still took its toll. By 1810, if not before, the children at Pecos had been vaccinated. In the summer of 1815, with the disease "already around," Governor Maynez had ordered the deputy justice at El Vado to send someone up to Santa Fe to be trained in how to give vaccinations, and also a child to carry the vaccine fresh. The following year, in December alone, at least eighteen Pecos died, of what Father García del Valle did not say, but all eighteen were adults.

Perhaps vaccination was allowed to lapse. On a visit to Pecos in March 1826, Father Caballero had buried seven in two days, all of them children. To a community of only forty persons, that was a terrible loss. Again in the winter of 1831-1832 smallpox stalked the El Vado settlements, and probably Pecos, the usual rest stop on the trail up to Santa Fe. Tradition has it that "mountain fever" or a "great sickness" finally led to abandonment, but that still has not been diagnosed. [56] Over the years, a succession of Plains Indian raiders had tested their valor against the fortress-pueblo of Pecos: Apaches, Comanches, and Apaches again. In the 1820s, when it was hardly more than a ruin, others tried their hand. These so-called "barbarians of the north" were likely Cheyennes and Arapahos. On the night of June 16, 1828, they steathily surrounded Pecos "closing even to the houses." Detecting them just in time, the Pecos "repelled them, firing on them." Next morning, according to a report by Juan Esteban Pino from the Cañón de Pecos, "they [the Pecos?]" followed the heathens' tracks "up onto the mesa by El Picacho toward the Rincón de las Escobas." From the tracks, they estimated that there were a considerable number headed as if for Galisteo. While the memory of this sort of thing probably figured in their decision to abandon the pueblo a decade later, it is too much to credit the new raiders with "bringing to a dismal end the history of the proudest pueblo in all New Mexico." [57] The valley's proliferating Hispanos, even while encroaching on mission lands with their crops and livestock, did offer more inviting spoils and some safety in numbers. Individual Pecos Indians who moved away from the pueblo during these final years are difficult to follow. Some certainly did. José Chama, for example, "native of Pecos" who married Juana Arias at San Miguel in 1817, a dozen years later showed up as a resident of Antón Chico. A witness to the Chama-Arias union, Miguel Brito, who was described in 1820 in the baptismal book as an "indio y vecino de Pecos," in 1821 was counted an infantry member of the El Vado militia, along with Chama. More than a decade after the final exodus, Lt. James H. Simpson of the United States Army was told at Jémez that there were only eighteen Pecos left in 1849. Fifteen lived at Jémez, one at Santo Domingo, one at Cañón de Pecos, and one at Cuesta in the El Vado district. Even today there are people in the village of Pecos who claim that great great grandmother was a Pecos Indian. And maybe she was. [58]

The Abandonment of Pecos Pueblo For years the faithful remnant of the Pecos nation had suffered reason enough to abandon their ancestral pueblo. What finally impelled them to do it is not known, although some wondrous myths have been invented to account for it. The year, tradition has it, was 1838, one year after a rabid New Mexico mob beheaded Gov. Albino Pérez. The move was calculated. They packed up their ceremonial gear, and, again according to tradition, arranged with the local Hispanos to take care of the church and celebrate the feast of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles, la Porciúncula, every August 2, which they do to this day. The refugees may have broken their trip at Sandía. Their final destination, eighty miles west of Pecos by trail, was Jémez, the only other pueblo that spoke the Towa language. Some of them may have had second thoughts and gone back. But they did not stay. [59] Commenting on the Pecos migration eleven years after it happened, a talkative Jémez told Lieutenant Simpson that,

Tourists and Tall Tales There were seventeen or twenty of them, led by Juan Antonio Toya. Father Caballero had recorded Toya's name and that of his wife María de los Ángeles at Pecos in 1826 when he baptized their seven-day-old son José Francisco. José Cota, or Kota, another of the emigrants, had joined with Rafael Aguilar in the fight to save the Pecos lands in 1829. By 1838, they and the others had reached their decision. They would go, at least for a while. [61] One year later, in September of 1839—a year that saw a quarter of a million dollars in goods rumble past on the Santa Fe Trail—the irrepressible Matthew C. Field, actor, journalist, and rover, spent the night with Dr. David Waldo in the Pecos church. His article about the "dilapidated town called Pecus," which he guessed rightly "in its flourishing days must have been inhabited by not less than two thousand souls," soon appeared in the New Orleans Picayune. "The houses now are all unroofed," he wrote,

Whereupon, in purple prose, Field launched into the tale of how Montezuma had chosen the Pecos as his people and had commanded them to keep a sacred fire burning in a cave until his coming again. Josiah Gregg claimed to have seen it smouldering in a kiva. For centuries the Pecos remained faithful to the trust. "Man, woman, and child shared the honor of watching the holy fire, and the side of the mountain grew bare as year after year the trees were torn away to feed the consuming torch of Montezuma." Then "a pestilential disorder came in the summer time and swept away the people." Only three were left: a venerable chief, his daughter, and her betrothed. The old man expired. The lovers grew weak. Just before death over came them, the young man had an idea. Taking a brand from the fire, he grasped his beloved by the hand and led her out of the cave. "A light then rose in the sky which was not the light of morning, but the heavens were red with the flames that roared and crackled up the mountain side. And the lovers lay in each other's arms, kissing death from each other's lips, and smiling to see the fire of Montezuma mounting up to heaven."

Still, Matt Field did not reckon he had done justice to the old man's story.

Montezuma, the perpetual fire, and a great serpent god "so huge that he left a track like a small arroyo" were off and running. [63] The era of Pecos as monument had begun. The living pueblo was dead.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||