Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Franciscan New Mexico The Franciscans' expanding ministry to the Pueblo Indians rested in 1616 on the fervor of sixteen friars. In addition to Santa Fe, they maintained "conventos," however tenuously, among the Tewa at San Ildefonso and Nambé; among the Keres at Santo Domingo, "ecclesiastical capital" of New Mexico, and at Zia; among the Tano at Galisteo and San Lázaro; and among the Southern Tiwa at Sand&icute;a, Isleta, and across the Manzanos at Chililí. Several other pueblos were designated visitas, or preaching stations. Still, no missionary worker had returned to the harvest at Pecos. [1]

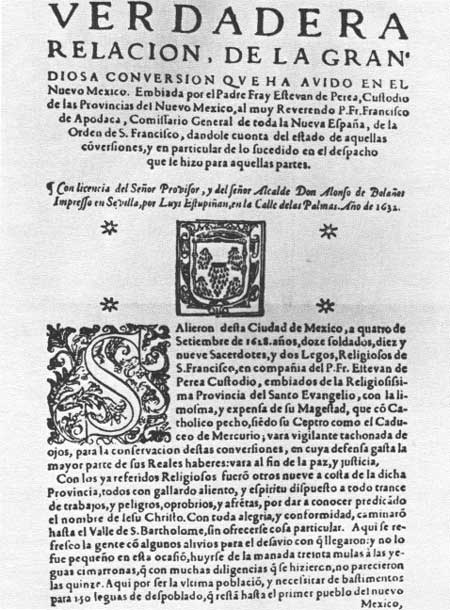

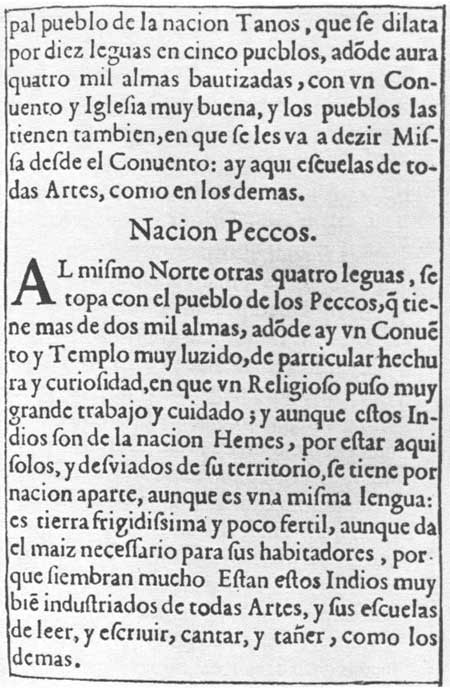

At about this time, the Order's superiors in Mexico City—galvanized, it would seem, by the Peralta-Ordóñez troubles—decided that the New Mexico field should be elevated to custody status. Previously, the local superior in the colony had worn the title comisario, which implied delegated, temporary authority. By erecting the missions of New Mexico into a semi-autonomous administrative unit with its own chapter, its own definitors, and its own Father Custos, the Holy Gospel Province was belatedly acknowledging the success and permanence of the enterprise. It was also girding up its loins. Still, because of the great distance from Mexico City, the missions' utter financial dependence on the crown, the example of the violent, headstrong Isidro Ordóñez, and the precedent for church-state conflict, the mother province did not surrender to the new custody as much autonomy as she might have. The New Mexico custodial chapter would not choose its own superior, as was customary. Rather he would be elected by the province. [2] The new entity would be known as the Custody of the Conversion of St. Paul, in honor of that saint who, on the feast of his conversion January 25, in the year 1599, divinely aided the Spaniards at the battle of Ácoma, almost certainly delivering the little Christian colony out of the jaws of Satan. [3] Zambrano Assigned to Pecos The long-awaited supply train of 1616 reached the missions in the dead of winter—before the end of January 1617—bringing among the baggage seven cold, trail-worn Franciscans and a patent from Mexico City naming as Father Custos of New Mexico the able and unbending Fray Esteban de Perea. Soon after, at his first chapter, Perea probably assigned one of the new friars to the populous pueblo of Pecos. Fray Pedro Zambrano Ortiz, guardian of "the convento of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de los Pecos" at least as early as 1619, was born in the Canary Islands about 1586. At the age of twenty-three, he had received the Franciscan habit at the Convento Grande in Mexico City along with two other young Spaniards. As was customary, the service of investiture took place in the evening after compline—last of the seven canonical hours—on Tuesday, October 27, 1609. Exactly a year later, his novitiate behind him, Fray Pedro pronounced his simple religious vows. When the mission supply caravan bound for New Mexico had headed out in the autumn of 1616, Zambrano, already ordained a priest, and half a dozen of his brethren rode with it. [4] Given the size of the pueblo de los Pecos—still reported at about two thousand souls—and its strategic location for pueblo-plains trade and intercourse, it is strange that the Franciscans delayed two decades in taking up their mission there. Certainly the harvest was potentially greater at Pecos than at Chililí. Perhaps the Pecos themselves, or a faction of them, had made it clear that they did not want a friar. Yet if that were the case, why did the veteran Esteban de Perea assign to Pecos an untried newcomer? The first convento of Our Lady of the Angels at Pecos was doubtless a makeshift affair. St. Francis had originally bestowed that name on Our Lady of the Assumption at Portiuncola near Assisi, the Order's mother church. It may be that Fray Pedro Zambrano and some of his fellow missionaries dedicated the new convento on August 2, 1617 or 1618, the very Franciscan feast of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de Porciúncula. Unwilling to move into the great pueblo itself—or forbidden to—the friar likely had living quarters built in or adjoining the southern end of a low, mostly unoccupied ruin, later expanded and peopled by the "Christian faction," the so-called South Pueblo. As for a church, Zambrano evidently asked some of the more favorably inclined Pecos to put up a temporary shelter where Mass could be said for them in some decency, perhaps the "jacal in which not half the people will fit" described by a successor in 1622. [5]

Opposition of Eulate Whatever Zambrano accomplished at Pecos, he did it in spite of the governor at Santa Fe, Don Juan de Eulate, veteran of Flanders and the Spain-to-Mexico fleet, has been characterized by France V. Scholes, the historian who knows him best, as "a petulant, tactless, irreverent soldier whose actions were inspired by open contempt for the Church and its ministers and by an exaggerated conception of his own authority as the representatives of the Crown." [6] A saying frequently attributed to Eulate summed up his allegiance: "The king is my patron!" For obvious reasons, he idolized the Duke of Bourbon, that French ally of Charles V whose troops had sacked Rome a century before. [7] A particularly avaricious exploiter of Indians in the friars' eyes, Eulate took office in December of 1618 and held it until 1625, precisely the years that Zambrano and his successors were trying to establish themselves at Pecos, to overturn the pueblo's "idols," and to raise up a monumental temple to the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

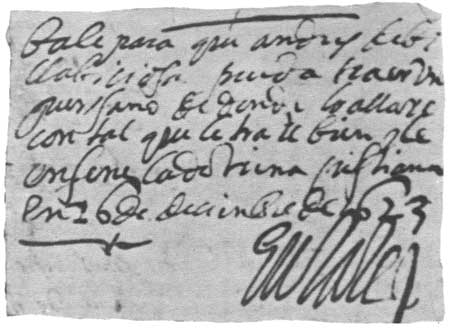

In testimony heard by Custos Perea—which eventually found its way to the Tribunal of the Holy Office in Mexico City—the Franciscans and their allies damned Eulate on a variety of counts, making him out a blaspheming ogre, a mortal enemy of the church, the faithful, and the Indian. To ingratiate himself with mission Indians and loosen the friars' hold, the governor deliberately encouraged these natives to continue their pagan ways. At Pecos in 1619, Father Zambrano heard that interpreter Juan Gómez, encomendero of San Lázaro and minion of the governor, was going about proclaiming that newly converted Indians did not have to give up their idols or their concubinage, at least not for many years. As a result, the Tanos of Galisteo and San Lázaro wallowed in sin while their missionary, Fray Pedro de Ortega, grieved. Eulate protected and favored Pueblo ceremonial leaders, "idolaters and witches," alleged Zambrano, "because they trade him tanned skins." [8] The governor paid no heed to Indian rights, charged the missionaries, only to Indian exploitation. He condoned forced labor, slavery, and even the kidnapping of "orphans." As a reward for loyalty to him, Eulate issued to his henchmen licenses on small slips of paper, vales, entitling them to seize one or more orphaned Indian children, a practice Zambrano witnessed at Pecos. "Like black slaves," these children, the friars averred, ended up perpetual servants in Spanish homes. The slips merely read: "Permit for Juan Fulano to take one orphan from wherever he finds him, provided that he treats him well and teaches him the Christian catechism." [9]

Sometime between mid-1619 and August of 1621, Fray Pedro Zambrano changed places with the missionary of Galisteo. During Zambrano's tenure at Pecos, he had built a temporary convento and dedicated it to Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles, but evidently no more of a church than the jacal. How much of the time the missionary was actually in residence at the pueblo is impossible to say. From his testimony, it would appear that he was often in Sante Fe. He may well have chosen to reintroduce the reluctant Pecos to Christianity by gentle stages. He hinted at resistance from an anti-Spanish element in the pueblo, a resistance that surfaced under his successor. Whatever else he managed, Pedro Zambrano did put Pecos on the missionary map. At Galisteo, and especially at its visita of San Lázaro, the reassigned Father Zambrano found the Tanos practicing idolatry publicly. When he reprimanded a native catechist for the sin of concubinage, the Indian replied that interpreter Juan Gómez was at that very moment en route from Mexico City with permission for the Tanos "to live as before they were Christians." Behind this and every other woe in the land, Zambrano saw the malevolent figure of don Juan de Eulate, "a man," in his words, "more suited to a junk shop than to the office of governor he holds." None of the friars, not even Custos Perea, was more constant or more zealous in his attack upon Eulate. In a scathing letter to the viceroy, setting forth the governor's venal acts, his defiant immorality, and his crass misuse of the natives, Zambrano characterized his adversary as "a bag of arrogance and vanity without love for God or zeal for divine honor or for the king our lord, a man of evil example in word and deed who does not deserve to be governor but rather a hawker and [a creature] of these vile pursuits." Years later, in 1636, Fray Pedro Zambrano Ortiz was still alive in New Mexico, still railing at a royal governor. [10]

Ortega Confronts the "Idols" Youthful Fray Pedro de Ortega cannot have been more than twenty-seven when he came to live with the Pecos. At Galisteo, native idolaters had made him doubt his calling. He would not give them the satisfaction at Pecos. He was determined also to build a church, a lasting structure large enough to hold all the Pecos. But his resolve was not enough. Both of his intentions fell short, not for any lack of zeal on his part, but rather because don Juan de Eulate prevailed against them. Ortega was a Mexican, a criollo born in Mexico City about March of 1593. His parents, Pedro Mateos de Ortega and Catalina de Ortega, were "not only noble," said Fray Alonso de Benavides, "but so wealthy that, although there were numerous children, more than seventy thousand ducats fell to the share of Father fray Pedro de Ortega alone." His father, who wanted him to be a secular priest, thwarted the lad's early desire to become a Franciscan. But when the elder Ortega died, eighteen-year-old Pedro straight-away renounced his inheritance and sought the friar's habit, which he received in the Convento Grande at the hour of Compline, Sunday, May 8, 1611. He professed on the same date a year later. [11]

Soon after ordination to the priesthood, which he must have received at the canonical minimum age of twenty-four, Fray Pedro volunteered for the missions of New Mexico. He had just missed the supply caravan of 1616. The following year however, the viceroy dispatched a new governor. It was Eulate. In his train, escorted by Capt. Francisco Gómez and a detachment of soldiers, Father Ortega and Fray Jerónimo de Pedraza, a medically skilled lay brother returning to the missions, traveled the long road to New Mexico. The young Franciscan and the crude governor quarreled en route. Somewhere along the camino real, while the party was camped, Eulate allegedly declared in front of everyone that marriage was the more perfect state than celibacy. Captain Gómez and Alonso Ramírez applauded. The others seemed to agree, which was too much for the boyish Fray Pedro who jumped up and tried to admonish the governor for saying such a thing. Eulate, smiling wryly as the friar recalled it, retorted in a most condescending manner "that religious didn't work, that all they did was sleep and eat, while married men always went about diligently working to earn their necessities." Fray Pedro was neither intimidated nor amused. "To that I replied that the sleep of John had been more acceptable to Christ Our Lord than the diligence of Judas." But his words were wasted on Eulate. [12] Don Juan and Fray Pedro had entered Santa Fe together in December 1618. Not long after, Custos Perea placed the new missionary at Galisteo. During his ministry there, which probably lasted not much more than one year, Fray Pedro had found himself on the defensive. Try as he might, the young Franciscan could not break the pernicious hold of the governor's men, the likes of encomendero Juan Gómez, who emboldened the Tanos to flaunt their old religion in the missionary's face. He apparently vowed to seize the initiative at his second mission.

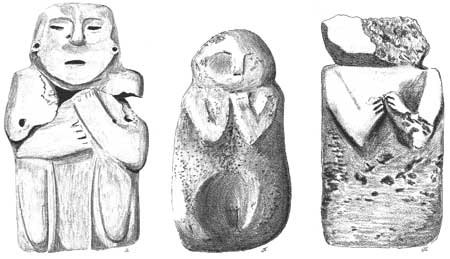

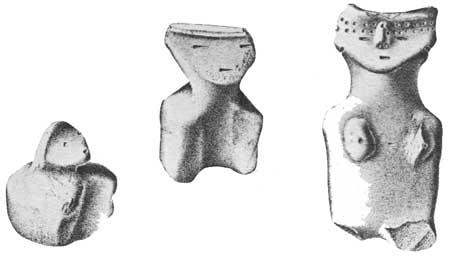

At Pecos, where he likely took over from Pedro Zambrano sometime in 1620, Ortega summarily launched a campaign to break the back of pagan idolatry. In a bold frontal assault, he rounded up and smashed "many idols," the clay, stone, and wooden figurines and effigies, the curiously painted stone slabs, and the other ceremonial paraphernalia they venerated. This was the first direct all-out Christian attack on the native Pecos religion. It would not be the last. Why did the Pecos, still relatively unsubjugated, still two thousand strong, stand by and watch? Given the irreverence of Governor Eulate, it is unlikely that Father Ortega relied on a large, heavily armed military escort to cow the pueblo. Obviously the Pecos were not agreed on resistance. A majority of them passively suffered themselves to watch their idols destroyed. Only a few ceremonial leaders objected. As a community, the Pecos were unable to act decisively, either to reject or to embrace the new order. Deep-seated internal dissension, unrelated to the Spaniards' presence, may have underlain this paralysis. Perhaps, too, the Pecos remembered their humiliation thirty years before at the hands of Castaño de Sosa, or Oñate's harsh punishment of the Ácoma survivors. Whatever the reason, once they had admitted the utility of the invaders' material culture, of horses and steel blades, the token acceptance of their supernatural baggage was not so hard. Yet in their hearts—as missionary after missionary lamented—the pagan Pecos changed little.

Three hundred years later, archaeologists digging in the ruined pueblo unearthed ceremonial caches containing numerous artifacts that had been smashed or otherwise "subjected to violent misuse." One greenish stone image about a foot tall, representing a squatting human figure with elbows resting on knees, like many of the other broken objects, had been reverently reassembled and laid in a specially prepared hiding place. At Pecos, as in central Mexico, idols hid behind altars, or beneath the earth of the plaza, and the people knew. [13] Resistance to Ortega's Ministry Not all the Pecos bowed meekly before Fray Pedro. The case everyone remembered involved an Indian "called by the evil name Mosoyo." He and a brother had gone about the pueblo propagating, in the friar's words, "a perverse doctrine, persuading the Indians that they should not go to church and that they should set up idols, many of which . . . I ordered smashed." Mosoyo was telling the Pecos that Gov. Juan de Eulate did not want them to go to Mass or catechism, to attend prayers, to obey their minister. The governor was their friend, not the friar! Ortega grew anxious. He could see Mosoyo's seductive message pervading the pueblo, undermining the gospel of Christ. He prayed and wept. When don Francisco Pérez Granillo, "a faithful and Catholic Christian," reined up at the pueblo to collect tribute, the Pecos encomendero—probably Capt. Francisco Gómez [14]—owed Eulate, Fray Pedro unburdened himself. Pérez was moved. He would do what he could in the Franciscan's behalf. Summoning together the entire pueblo in the presence of their missionary, the Spaniard ordered the agitator Mosoyo brought forward. There, in front of everyone, he rebuked the Indian. Even then, Mosoyo refused to admit that he had proclaimed his seditious lies in Governor Eulate's name. The interpreters, native captains, and the rest of the pueblo clamored that he had. At that, Pérez delivered an oration—which presumably lost something in translation—assuring the Pecos that the governor of New Mexico could not have meant any such thing. He exhorted them to obey the holy precepts of the church and its minister, "telling them that the doctrine the Fathers were teaching them they were also teaching the Spaniards and the latter obeyed it as they did their parents and teachers. Regarding this he gave them many sound reasons and examples, whereupon they all were satisfied." Having done this good Christian deed, Francisco Pérez Granillo stepped down rather pleased with himself.

Governor Eulate's Wrath It was night before he rode back into Santa Fe. He made straight for the governor's quarters to report on the tribute payment and on the situation he had found at Pecos. He related exactly how he had admonished the Indians, assuming that the governor would be grateful to him "for having defended his honor and the cause of God." Instead, Eulate exploded. By whose order, he demanded, had Pérez meddled in affairs at Pecos. That was none of his damn business! Stung by such "pharisaical words," Pérez Granillo made his exit, having, as he put it, formed a bad opinion of the governor. As for Francisco Mosoyo, that "great idolater and witch about whom our Father Custos has compiled an extremely full report," Ortega tried to rehabilitate him and his like-minded brother, "assigning them no greater penance than placing them in the home of Christian and honorable Spaniards." When Eulate heard what the friar had done, he bellowed. The accused must be released at once and sent back to Pecos with a letter informing Fray Pedro that they were not to be harmed but favored. What more could the missionary do? [15]

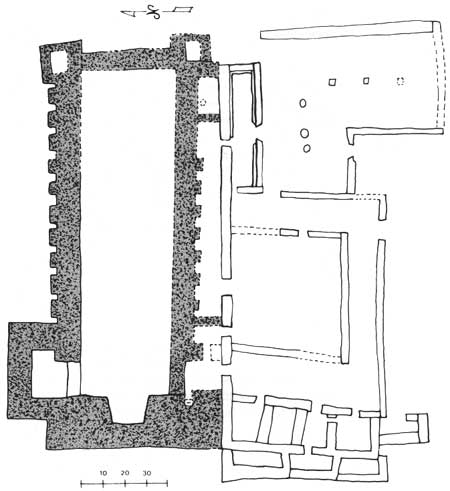

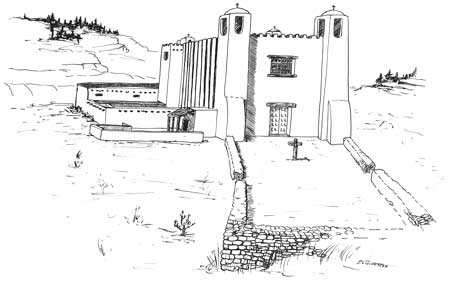

A Proper Church for Pecos At the beginning of the 1620s, the friar at Pecos resided, it would seem, in a modest several-room adobe convento, abutting the "South Pueblo" ruin. He celebrated Mass in a nearby jacal too small for even half the people. Yet well before the end of the decade, his successor presided over "a convento and most splendid temple of singular construction and excellence," the largest in New Mexico. Fray Pedro de Ortega, who gets none of the credit from Benavides—probably at his own insistence—must have had a hand in this ambitious project, at least in its early stages. [16] There is no doubt that Ortega planned to build a church at Pecos. Several contemporary witnesses testified that he had borrowed teams of oxen from certain Spaniards to haul rock and timber. He already had the animals at the building site in 1621, presumably on the job. Surely before arranging for draft animals, he must have chosen the site and staked out the foundations. That would at least confirm to the credit of Fray Pedro the location as well as the original plan and orientation of the new church. The site lay a good six to seven hundred feet south of the pueblo proper at the opposite end of the same long mesilla, closer and less isolated than Father San Miguel's 1598 church, but hardly in the laps of the Pecos. [17] To picture the relationship in space of pueblo and projected church, with "neutral zone" between, it is worth pirating a few lines from seaborne ex-Army chaplain, historian, and poet Fray Angelico Chávez:

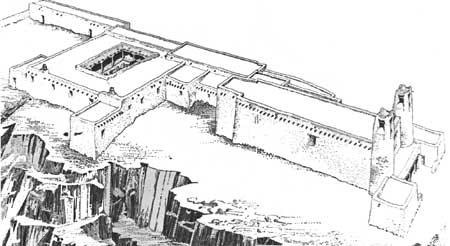

To carry Fray Angelico's naval analogy a little further, the grounded dreadnought rides with her broad, ill-shapen bow to the north, as if a norther had swung her around at anchor. Amidships aft she tapers noticeably, all the way back to the slender stem. Precisely there, athwart the poop deck, still within the ship's railing but as far aft of the main superstructure as possible, the friar meant to set his church. It would face to starboard, to the east like most seventeenth-century New Mexico churches. Because the bedrock deck of the mesilla was not entirely level at its southern or stern end, but rather humped in the center, preparation of an area spacious enough to contain a large church with adjoining convento and cemetery required considerable fill. The massive foundations would rest entirely on the bedrock but they would be deeper at the two extremes than in the middle. [19] Father Ortega may have overseen the hauling of fill with his borrowed oxen, perhaps even laying up some of the stone-faced, rubble foundations, but that was about all. Once again Governor Eulate intervened.

Eulate Halts Construction At every turn, to hear the friars tell it, Eulate thwarted their missionary program. He abused or threatened mission Indians who worked for or cooperated with the Franciscans. He opposed mission expansion, denying escorts to friars who wished to carry the gospel to neighboring heathens, even though he exacted tribute and services from such people whenever he could. When certain encomenderos, like Capt. Francisco Gómez, volunteered as escorts, Eulate ordered them back. But perhaps most scandalous of all, the governor openly obstructed the building or repairing of churches and conventos, even threatening to hang the Indian laborers who refused to quit. With his outrageous bullying, he brought work on the Santo Domingo and San Ildefonso churches to a standstill, but the one they were all talking about was Pecos. A number of Spaniards had lent Father Ortega their oxen, presumably in the off season, to help build his grand church. One such cooperative citizen was diminutive Canary Islander Juan Luján, a resident of New Mexico since 1600. Eulate accosted him. If he did not send immediately to Pecos for his oxen, he could count on a fine of forty fanegas of maize! Ensign Sebastián Rodríguez, who had traveled to New Mexico with his wife in the company of Eulate and Father Ortega back in 1618, also had oxen on the Pecos project, as did Ensign Juan de Tapia. With them, the governor was even more brutal. If they did not go at once and bring back their animals from Pecos, "he would dispose of them and the oxen." When they protested that they had no horses to ride, Eulate yelled at them "to go on foot and bring in the whips, the yoke straps, and the yokes on their own backs!" [20] The governor had made his point. "In order to avoid disputes and strife," Father Custos Esteban de Perea reluctantly ordered his religious to stop all building. [21] At Pecos a frustrated Pedro de Ortega complied. Perea, a fighter if ever there was one, cannot have meant the stoppage as more than a temporary measure calculated to buy time. He had petitioned his Father Provincial to allow him to come to Mexico City and present in person the friars' case against the governor. In August 1621, he appealed to the people of New Mexico to denounce anyone guilty of offenses against the church. At least seven friars responded—including Fathers Ortega and Zambrano—each verifying and expanding upon the list suggested by their superior. Eulate was reported to be in a rage, vowing to have two hundred lashes applied to anyone caught informing against him. To some New Mexicans, it must have seemed as though open warfare between the two factions was about to erupt again as it had less than a decade before. Just then, the supply caravan arrived. Father Perea's term of office had ended. A new Father Custos, an appeaser, had been dispatched from Mexico City. Instructions from the viceroy to both the prelate and the governor urged restraint and mutual aid. For about a year, a welcome spirit of forbearance overlay the quarrel between church and state. [22] At Pecos that meant a resumption of building, not under the eye of Fray Pedro de Ortega but of another Franciscan, unquestionably the most effective missionary ever to live among the Pecos. Andrés Juarez of Fuenteovejuna By the time he moved in at Pecos late in 1621 or early in 1622, Fray Andrés Juarez was a scarred veteran, He had ridden muleback to New Mexico a decade earlier, in the train of Comisario Isidro Ordóñez, who later imprisoned him. While guardian at Santo Domingo, he had suffered the abuse of Governor Eulate's men. At Pecos he would endure the trials of thirteen years, longer than any other missionary in the pueblo's history.

He was from Spain, from the pleasant oak-studded hill country northwest of Córdoba. His parents, Sebastián Rodríguez Galindo and María Juárez, were natives of Fuenteovejuna, where Andrés was born in 1582, six years before the Armada. All over Andalucía people knew the town for its hearty vino de los guadiatos, the product of vineyards that grew along the banks of the Río Guadiato, and for its rich honey, prized since Roman times. The variant spelling of Fuenteovejuna, which translates Sheep Well, is Fuenteabejuna, Bee Well. Still, it was history, and the incredibly restless pen of Lope de Vega, that conferred upon the town its enduring fame. [23] Andrés Juárez and Lope de Vega were contemporaries. As a native son of Fuenteovejuna, Juárez, who chose to use his mother's surname instead of his father's, had heard the story told and retold even before Vega popularized it. He was reminded of it every time he entered the parish church of Nuestra Señora del Castillo. On this spot in the eighth century, the Moslems had built a fortress. The Christian knights who stormed back five hundred years later made it a castle. When the crusading military order of Calatrava received the town as a fief, the castle became the palace of the Order's knight commander, or comendador. The deeds of Comendador don Fernán Gómez de Guzmán, and Fuenteovejuna's shocking response, were recorded in the Crónica de la Orden de Calatrava. From its pages, the ebullient libertine Lope de Vega, "Nature's Wonder," mined the story and shaped it into one of the most intense dramas of Spanish classical literature. It is a story of heroic community solidarity, of mutual action and loyalty in the face of cruel tyranny. The comendador, Fernán Gómez, personifies the jealous and unruly nobility. When not inciting his fellow knights against the Catholic Kings, he delights in seducing the women of Fuenteovejuna, virgin and married alike, sadistically beating the men who object. At last by force he deflowers the comely, high-spirited Laurencia. In her shame, she stands before the town elders and harangues them to vengeance. The people unite, storm the castle, and tear the evil Gómez limb from limb. An investigator dispatched by the king subjects men, women, and children to judicial torture, asking each the question "Quién mató al comendador?" No one breaks. Each replies "Fuente Ovejuna, Señor. Y quién es Fuente Ovejuna? Todos á una!" Throwing themselves on the mercy of Ferdinand and Isabella, the town as a whole is pardoned and royal justice prevails. This drama, known so well by fuenteovejunense Andrés Juárez, was given to the world by Lope de Vega in 1619—while Juárez was guardian at Santo Domingo. The playwright called it simply "Fuente Ovejuna." [24] Entry no. 554 in the Convento Grande's "Libro de entradas y profesiones" records the investiture on Thursday, December 4, 1608, of "Andrés Xuárez, native of Fuenteovejuna in the diocese of Córdoba." It gives no hint of when he sailed from Spain to America. He was old enough when he entered the Order, twenty-six, to have had all or most of his priestly training behind him. Concluding his novitiate, he professed his vows on December 5, 1609. Two years later, when recruiter Fray Isidro Ordóñez returned a second time from the missions of New Mexico, six priests and three lay brothers volunteered. Father Juárez was among them. [25] Since Ordóñez' previous visit to the capital, Oñate's friend, two-term viceroy Luis de Velasco, had gone back to Spain and the archbishop of Mexico, the famed baroque Dominican García Guerra, had succeeded him, ruling as both primate of the Mexican church and chief of state. To unwashed crowds who gathered, mouths agape, to glimpse the great man gesture from his glittering carriage, and to finely attired dignitaries who waited upon his every command, it seemed that Fray García, despite earthquakes, floods, and physical distress, thoroughly relished his awesome dual authority. Judging by the subsequent actions of Isidro Ordóñez in New Mexico, that image was not wasted on the Franciscan. [26]

The Supply Train to New Mexico The officious Ordóñez busied himself with details of supply. By order of the archbishop-viceroy, dated October 1, 1611, he oversaw the purchase, stockpiling, and transportation of goods for the missionaries in the field as well as for those he would shepherd to New Mexico himself, everything from oil paintings of saints in gilded frames, damask vestments, huge illuminated choir books containng introits and antiphonies for the saints' days to forty pairs of sandals, "twelve large latches for, church doors with their locks, keys, and ring staples, and one hundred twenty Sevillan locks for cells with their keys," from two-hundred-pound bells to pins, from vintage wine, raisins, almonds, and peach and quince preserves to olive oil and vinegar. Early in 1612—about the time Viceroy don fray García Guerra breathed his last—they set out, "giving thanks to God," Ordóñez, Juárez, and eight other friars astride saddle mules that had cost the crown 129 pesos 2 tomines each with full trappings. Erect, dark-skinned Capt. Bartolomé Romero, veteran of the Oñate conquest, commanded the armed escort. Whip-cracking muleteers, high aboard the twenty heavy, groaning wagons overloaded with the mission goods, cursed their mule teams and their luck. Sundry servants, animals, and hangers-on ate dust at the rear. [27] The journey north from Zacatecas, which they must have left late in March, was hell. But for a few poor settlements, the country through which they rode for a hundred leagues was "desolate . . . almost without any convenience or refuge." The friars, "almost all raw recruits and hardly world travelers," found themselves forced to do without necessities, "things we could have got in Mexico City." The temperature climbed. They griped. To a man, said a harsh critic of Ordóñez, they laid the blame to Fray Isidro "for having perversely misinformed us about the road." One lay brother lost heart and deserted. When the superior admonished the others at the Río Florido to make do in the knowledge that they would appreciate the provisions even more in their isolated missions, they tightened their cords. After all it was not material comfort that had moved them to become missioners, rather the love of God. Therefore, "with confidence in His Divine Majesty and in accord with what Father Ordóñez proposed and promised, we traveled on and suffered en route what only Our Lord knows." [28]

Juárez Tested Neither did the suffering cease when they reached New Mexico. Father Ordóñez had allegedly tongue lashed several of the friars on the road. He continued to do so in the missions. Juárez' turn came soon enough. Evidently assigned first to the convento in Sante Fe where he witnessed the shooting incident involving Governor Peralta, Fray Andrés suffered Ordóñez' wrath on several occasions in public. It mortified him. The sin of vengeance welled within his breast. He had to get out, to carry word of the local prelate's excesses to his superiors in Mexico City. Juárez would gladly pay for his desertion with whatever penance they prescribed. The attempt of Andrés Juárez to flee New Mexico, like most everything else known about the regime of Comisario Ordóñez, was recorded by Fray Francisco Pérez Huerta, who considered Ordóñez a monster. Whatever the facts of the case, Pérez Huerta's interpretations were sure to be colored. According to him, Father Juárez hired a manservant for the journey and made secret plans to slip away. The servant informed Ordóñez. Rather than confront the scheming friar, the comisario gave him the rope to hang himself. Unaware that his servant had betrayed him, Juárez headed for Galisteo to provision himself. There the Father Guardian gave him what he could, at the same time trying to talk him out of taking so rash a step. Juárez would not listen. It was in God's hands now. If he did not go, he knew he would "either hang himself or kill the Father Comisario." Pérez Huerta gave him the arquebus and horse armor he wanted. Meanwhile, having sworn the other friars to silence under their vow of obedience and on pain of excommunication, Ordóñez laid a trap. Waiting undercover just far enough down the road to establish without a doubt Juárez' intention, he grabbed the startled friar, confiscated the letter of Pérez Huerta he was carrying to Mexico City, and soundly rebuked him in front of a layman. "Straight-away they took him prisoner to the convento of Santo Domingo where he was absolved and actually put in the jail for a term of four months."

Confinement seemed to take the fire out of Fray Andrés, at least for a while. It was Ordóñez who left New Mexico. Juárez became guardian at Santo Domingo. Unlike Custos Perea and Father Zambrano, he did not attack Governor Eulate. He saw work on the Santo Domingo church stop because of the governor's threats. Still, when the opportunity to testify against Eulate presented itself, Juárez had little original to say. He did not even mention what allegedly happened on Sunday, August 1, 1621. He had gone in to say Mass for the Spaniards of Sante Fe, then returned to preach in Santo Domingo. After his sermon, Capt. Pedro Durán y Chávez, one of Eulate's closest supporters, was supposed to have quipped that what Father Juárez needed was a good punch in the nose. [29] Respite in Church-State Conflict The peacemaker arrived in October 1621. Sent out from the Convento Grande, Fray Miguel de Chavarría, newly appointed custos of New Mexico, made no pretense. He warmly embraced Governor Eulate. Ex-custos Perea blanched. Here once again was Christ in the embrace of Judas Iscariot. The two friars' exchange at chapter must have been tense. There was no common ground save their faith. Veteran Perea, mulish protector of the church, knew what the perfidious Eulate was capable of. Chavarría, the administrator from headquarters, had come to restore harmony. The viceroy had decreed it. Surely, as God's children, they could work things out. Perea did not think so. His one hope to save the church in New Mexico from the anti-christ Eulate was to present the facts in person in Mexico City. But Chavarría would not let him go. There was a reason for Custos Chavarría's conciliatory attitude toward Eulate, beyond Perea's allegation that they were old buddies. The viceroy's instructions had plainly laid the onus on the Franciscans. With the contending parties' "letters, missives, memorials, depositions, and other documents" before them, the viceroy and his advisers had been more offended by the picture of a royal governor, excommunicate, shackled, doing humiliating public penance before omnipotent friars than by alleged crimes against the church and morality. The friars must cease their interference in secular affairs. Getting down to specifics, the viceroy admonished both custos and governor not to meddle in the annual elections of native pueblo officials; he cautioned the friars not to obstruct the collection of tribute from pueblos like Pecos that had already been granted in encomienda, at the same time ordering that no tributes be exacted from unconverted pueblos like those of Zuñi and Hopi. He instructed the governor to provide escorts for the friars and forbade him to let Spaniards run livestock within three leagues of the pueblos; he told the missionaries to stop cutting the Indians' hair as punishment; and he tried, from fifteen hundred miles away, to decree an end to illegal use of Indian labor by colonist and missionary alike. Even though abuses persisted, the heads of church and state now greeted each other in public, while ex-custos Perea fumed. [30]

Juárez to Pecos; Ortega to Taos At Pecos, the missionary effort picked up. Just why Custos Chavarría recalled Fray Pedro de Ortega and moved Andrés Juárez over from Santo Domingo is not clear. Certainly Ortega's abortive attempts to discipline the idolater Mosoyo and to build a church had put him in a compromising position. His smashing of Pecos idols had sorely strained his relations with the people. From all indications, Father Juárez—like the renowned sixteenth-century Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún—was more tolerant, more willing to accept the Pecos as they were, to learn their language and their ways, and to use this acquaintance to guide them toward a Christian salvation. To change their hearts, he relied not on destruction of pagan symbols, but rather on the infinite grace of God, the God of the New Testament. As for Fray Pedro de Ortega, he took up a heavier cross. Assigned to the conversion of Taos, he all but won the martyr's crown. In the beginning, "the idolatrous Indians illtreated him to prevent him from remaining there and preaching our holy Catholic faith. For food they gave him tortillas of maize made with urine and mice meat, but he used to say that for a good appetite, there is no bad bread, and that the tortillas tasted fine." When they refused him lodging, he laid up a shelter of branches and persevered in the cold. First he converted "the principal captain." Others followed and helped him build a decent convento. Then one night as he sat by the fire, an Indian, an ally of "the priests of the idols," leveled an arrow at him. Just as the would-be assassin was about to let fly, a Spaniard's dog startled him. He ran. The dog gave chase. Before he could scale the garden wall, the animal was on him tearing his flesh. They found him dying. There was time only for the friar to absolve and baptize him. "When all those who were not yet baptized and converted saw this punishment from God, they conceived a great love and veneration for the blessed father and [they themselves] were converted and baptized." [31] Church Building Resumed While Pedro de Ortega was reportedly winning over the disinclined Taos, Fray Andrés Juárez resumed construction at Pecos. How much he could utilize of what Ortega had done before the stoppage in 1621, Juárez did not say. But by the time Custos Chavarría visited the pueblo, presumably in mid-1622, the structure was taking shape. Fray Andrés, writing to the viceroy on October 2, explained

Juárez was an accomplished beggar. He also wanted some new priestly vestments because the old ones were "already all torn to pieces." Either he was bidding for an ayuda de costa from the royal treasury, the traditional one-thousand-peso initial grant to new churches for bells, altar furnishings, vestments, etc.—which may already have been spent on Pecos—or for a special pious donation. Whatever the case, the astute Franciscan vowed that the altar piece would be installed at Pecos in the viceroy's name so that "the Blessed Virgin might reward the concern of Your Excellency and so that these poor recent converts might be brought to a knowledge of the greatest truth in Our Holy Catholic Faith." He kept pressing. Pecos was not just any pueblo, "as Your Excellency can verify." To Pecos every year came numerous "heathens, called the Apache nation," people from the plains.

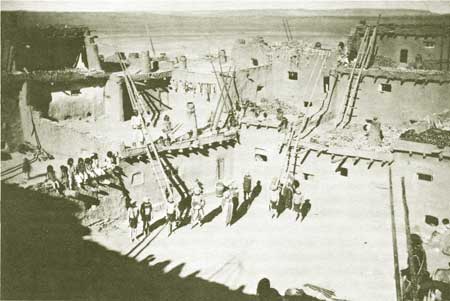

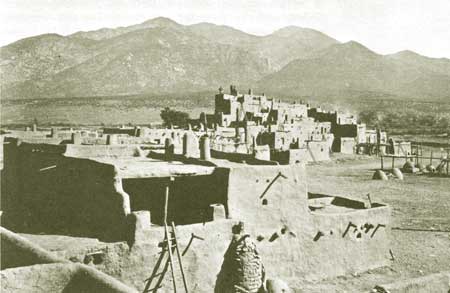

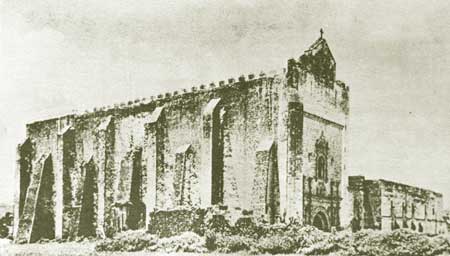

That year, 1622, building preoccupied Andrés Juárez. The supply wagons were finally about to return to Mexico City after many months' delay. Like some of his fellow missionaries, Fray Andrés took this opportunity to write the highest-ranking official in New Spain. Of nine letters sent, only his was non-partisan. He alone confined himself to the immediate needs of his mission, while the others took sides, most of them, like Zambrano Ortiz, vehemently denouncing Governor Eulate and, by implication, their superior who had tried to appease him. Custos Chavarría was also leaving. After only a year in the missions, he felt compelled to return to Mexico City to defend himself against the barbs of his fellow Franciscans. In letters to the viceroy, the Convento Grande, and the Inquisition, Perea and his party had flayed Governor Eulate, citing again and again his obscene disregard for the viceroy's instructions. At the same time, they had portrayed Custos Chavarría as the governor's toady. Few friars dared stand by Chavarría. One who did was old Alonso Peinado. He praised the custos' efforts to calm the troubled waters and to propagate the faith, especially among the Pecos, Jémez, Taos, and Southern Tiwas. With another six friars he would have reduced the Piros and Tompiros, "who are on the verge." He had encouraged church construction. At Santa Fe, the foundations had been laid for a convento and a church that Father Peinado believed "will be the best in this land," Evidently he had not seen Pecos. [34] A Church to Match the Pueblo The Pecos project was monumental. The pueblo's size, consequence, and self-respect dictated that its church be the best in the land. Plans called for a nave as wide inside as the largest available pine beams would span, forty-one feet at the entrance, tapering to thirty-seven and a half feet at the sanctuary. Height of ceiling would approximate width. The number of Pecos Indians, that is the size of the potential congregation, determined length—a remarkable one hundred and forty-five feet from entrance to the farthest recess of the apse. Wall thickness varied from eight to ten feet down the sides between buttresses, to twenty-two feet at the back corners where two of the planned towers would rise. [35] Outside, the massive structure, with its rows of rectangular ground-to roof buttresses up the lateral walls, its six towers, and its crenelated parapet would look as much like a fortress as a church—a reflection not of Father Juárez' fear of attack, but rather of his European heritage. 300,000 Adobes Such an undertaking laid a heavy burden on the Pecos. Each sun-dried mud block, about 9-1/2 by 18 by 3 inches, weighed forty pounds or so. Gray to black in color and containing bits of bone, charcoal, and pottery, the earth must have been dug from the trash mounds that had accumulated along the edges of the mesilla. The job would require 300,000 adobes. While the men hauled earth and water and the great quantity of wood needed for scaffolding, the actual laying up of walls in Pueblo society was women's work. "If we force some man to build a wall," wrote Fray Alonso de Benavides, "he runs away from it, and the women laugh." [36] The friars were always quick to condemn Juan de Eulate as an "enemy of churches" when he opposed their construction. Yet his complaints to the viceroy that the missionaries demanded endless free labor from the Indians to build and maintain excessively grandiose structures, that such work kept the natives from cultivating their fields, and that it monopolized the oxen and skills of neighboring colonists, may have been founded as much on fact as on his own greed and irreverence. [37] The Pecos, no mean builders themselves, had never raised up anything like this before. The whole concept of enclosing within walls forty feet high so immense a volume of unutilized space to the glory of God was foreign to their thinking. Such walls, as well as the buttresses and towers, all of which emphasized the vertical, went against their tradition of building in horizontal layers. Despite the limits imposed on Fray Andrés by the environment—by a friable, impermanent building material of low plastic potential and, to a lesser degree, by a work force untrained in European techniques—he still managed to open the Pecos' eyes with other architectural innovations: winding stairs up the inside of a tower, swinging doors, corbels and crenelations, and many more.

The work took longer than he had reckoned. Seasonal demands on the Pecos, agriculture, hunting, and trading, the inevitable shortages of craftsmen, oxen, or materials, and once again the formidable opposition of Governor Eulate combined to wreck his schedule. In his letter of October 1622 to the viceroy, Fray Andrés had expressed the hope that the church would be finished the following year. It was not. On one of his trips to Santa Fe to say Mass, the Pecos friar and the royal governor had exchanged words over the obeisance a priest should render a governor in church. This led to allegations that don Juan had denied that one should adore the cross. Later the missionary complained that only after three years, more or less, had Eulate granted him "the aid of oxen he had requested from the citizens for construction of the Pecos church." [38] Depending on the date of his initial request, the end of three years would have fallen sometime late in 1624 or in 1625. In January 1626, New Mexico's seventeenth-century promoter par excellence, Fray Alonso de Benavides, Franciscan custos and agent of the Inquisition, entered Santa Fe with due pomp and ceremony. He stayed more than three years, stimulating vitally the missionary effort. He set out new missions, dedicated churches, and even labored in the vineyard himself among Piros, Jémez, and Gila Apaches. Later, during his vain bid for a bishop's miter, the resourceful Benavides claimed full credit for everything of note that had occurred in New Mexico during his administration. But he did not claim the Pecos project. Fray Andrés Juárez had finished before his arrival. The Impression of Fray Alonso de Benavides Still, Father Benavides recognized Juárez' achievement as "a convento and most splendid temple of singular construction and excellence on which a friar expended very great labor and diligence." [39] Adjoining the south wall of the church, the convento, with its rooms and covered walkway secluding the usual interior patio, must have gone up right after the church. On the west side it was two stories. Here Fray Andrés had his quarters, and on the second floor off his cell, a mirador, or enclosed balcony, "which looks out toward the villa [Santa Fe]." [40] Although it is tempting to conjure up a festive dedication on August 2, 1625, the building dates for the monumental Pecos mission, encompassing whatever start Father Ortega may have made, can be drawn no tighter than 1621 and 1625.

Architectural Marvel Few of Fray Andrés Juárez' contemporaries left descriptions. Yet they must have been impressed. To mounted Spaniards dropping down through piñon and juniper out of the mountains to the west, come to collect tribute or to trade for hides and slaves, or to a party of Plains Apaches approaching from the east, their loaded dog travois inscribing a hundred parallel lines in the loose dirt, the Pecos church with the sun on its white plastered walls must have seemed at most a wonder, at least an unmistakable landmark. Architecturally it was unique, a sixteenth-century Mexican fortress-church in the medieval tradition, rendered in adobe in the baroque age at the ends of the earth. No other pueblo church, with the possible exception of San Gregorio de Abó, built a decade later and of stone, so completely belied its heritage. Pecos was pure transitional, from transplanted European fortress-church, built of masonry, permanent and dynamic, to New Mexico mission, of earth, field stone, and wood, impermanent and static.

By massing adobe, the friar-architects of New Mexico achieved the height they wanted and, at the same time, gave to their churches distinctive unbroken expanses of exterior wall and a pylon-like silhouette. At Pecos, Juárez conceded to the massive walls. Half a century and half a continent away, Franciscan chronicler Agustín de Vetancurt, wrote of the "magnificent temple" at Pecos "adorned with six towers, three on each side" and with walls "so thick that services were held in their recesses." [41] Yet with his buttresses, Juárez clung to the traditional, as if he wished to create the illusion of masonry. At Pecos, the walls rose almost straight, and the buttresses broke up the smooth exterior texture. Instead of countering the thrust of rib vaulting, as they would have in a Mexican fortress-church, here they bore only the dead weight of a flat roof. Horizontal beam and lintel replaced vault and arch in New Mexico. In other ways too, with windows for example, Fray Andrés may have sought to work the materials at hand into something a European could recognize as a church.

George Kubler, distinguished author of The Religious Architecture of New Mexico, would have delighted in analyzing, disassembling, and reassembling Juárez' noble monument. But he and everyone else were wholly fooled by the smaller, cruder eighteenth-century church built right on top of its crumbled ruins. Not until 1967, during excavation and stabilization of the more recent church by the National Park Service, did archaeologist Jean M. Pinkley hit upon the imposing foundations of the parent structure. Her find vindicated both Benavides and Vetancurt. Concluding the preface to a fourth edition of his classic, Kubler paid tribute to Fray Andrés Juárez. Architecturally his church "now emerges as the 'prime object' in seventeenth-century New Mexico." [42] Missionary's Routine The great church became at once a revelation and a focus. No Pecos who worked on the structure, no Apache who saw it for the first time, could help but be impressed by this temple to the invaders' God, plainly a virile God who had shown His followers many advanced ways. Neither could an Indian who expressed interest or awe escape hearing more about the love of this God for mankind and His offer of salvation through baptism. This towering new church epitomized the strong ministry of Andrés Juárez. Custos Benavides, ever prone to pious exaggeration, claimed that Pecos had "more than two thousand Indians, well built houses three and four stories high and some even more. They are all baptized and well instructed under the good administration of Father fray Andrés Juárez, a great minister and linguist." [43] Command of the Pecos language, to whatever degree, must have enhanced Juárez' effectiveness as evangelist, teacher, and administrator, freeing him from utter dependence on the generally ill-trained interpreters. Although Fray Andrés left no description of his regime at Pecos, we can get an idea of what it entailed from Benavides' idealized composite view.

Effects of Juárez' Ministry For a dozen and one years, Andrés Juárez kept the Pecos clock running. At times, as he looked out from the steps of his church over the faces of the Pecos gathered, men on one side, women on the other, in the atrio, or courtyard that doubled as cemetery, to hear him discourse on the immortality of the soul, he must have felt the despair expressed so often by his fellow missionaries. Would he ever penetrate their hearts? Prodded by native catechists called fiscales, they could say by rote the Creed or the Pater Noster, but what did these words mean to them? They plainly enjoyed the rich ceremonialism of the Mass, the singing, and the feast-day processions, but what did they know of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ? Juárez knew that the gobernador they elected annually in compliance with the viceroy's instructions was only a figurehead put forward to deal with the Spaniards. Their traditional headman, whom the Spaniards labeled the cacique, and "the priests of the idols," as Benavides called them, continued to propitiate Corn Mother and all the other intimate forces that ordered the Pueblo world. They simply went underground whenever the missionary put the pressure on. He could punish idolaters at the mission whipping post, along with chronic truants, but that only made them resentful and more secretive. Once he had instructed the Pecos and baptized them, once he had placed the visible church at their disposal, all he could do was keep them going through the motions. For anything more profound, anything resembling genuine "conversion," Fray Andrés waited on the Holy Spirit. Some of the Pecos, for reasons of their own, may have responded to Juárez' forceful Christian ministry more positively than others. By the end of the century, a vicious intramural rift between progressive and conservative factions would tear the great pueblo apart. If the roots of this rift reached back before the Spaniards' coming—perhaps to a fundamental division between an individualistic, liberal faction of traders influenced by contacts with other peoples and a more traditional, agrarian, community-oriented Pueblo faction—surely the "Christianization" of Pecos by Andrés Juárez increased the tension. It is possible that a group of Pecos, previously joined together in one moiety, or as a clan, a kiva group, or society, decided at this time to align themselves more visibly with the invaders by renovating the "South Pueblo," almost within the shadow of Juárez' church. [45]

The Pecos Become Carpenters One thing Fray Andrés did in the realm of things material affected Pecos for the rest of its life. It may also have hastened the pueblo's demise. The Franciscan introduced a craft that became a specialty with the Pecos. It afforded them a skill much in demand throughout New Mexico. It brought them some revenue and some esteem. It also gave them a certain freedom of movement, as they went about from mission to settlement plying their skill. Broadening to the individual, this mobility loosened the hold of the community and made it easier for a Pecos and his family to relocate as the pueblo broke up in the eighteenth century. This craft was carpentry. [46] "It is a mountainous country," Benavides wrote of the Pecos area, "containing fine timber for construction, hence these Indians apply themselves to the trade of carpentry." During construction of his church, Father Juárez had brought in Spanish craftsmen, probably ship carpenters recruited in Spain in 1604 by Oñate's brother, to train the Pecos men. [47] Carpentry tools were among the standard items freighted north in the mission supply wagons: axes, adzes, small hand saws and long two-man saws, chisels, augers, and planes, as well as spikes, nails, and tacks. [48] So dedicated to carpentry did the Pecos become that the great purge of 1680 hardly interrupted their work. As soon as the Spaniards reappeared, the carpenters of Pecos went back to work. Eighteenth-century reports tell repeatedly of lumber prepared by the Pecos and delivered to Santa Fe, of doors and window frames and beds made to order for Spaniards and Indians alike, and of skilled woodworking on New Mexico churches. Sometimes their customers failed to pay. In 1733, four Pecos carpenters filed a belated claim against the missionary at Taos for a job they had done on his church "more than ten years before." [49]

Plains Apaches and Pecos Even while he oversaw the myriad details of his ministry to the Pecos—slaughtering a sheep, singing the Salve Regina, hoisting a roof beam—Fray Andrés Juárez did not forget the nomads. He had meant what he said in his letter to the viceroy. His mission would become a light unto the Apache nation "so that they want to be baptized and converted to Our Holy Catholic Faith." He could not have forgotten them if he wanted. Every year about harvest time, from late August to October, they showed up to trade, hundreds of them. Some of them wintered nearby, as Pedro de Castañeda phrased it, "under the eaves" of the pueblo. The arrival of these vaqueros—so-called because they followed the vacas de Cíbola, the Cíbola cattle or buffalo— was always an occasion. "I cannot refrain from relating a somewhat incredible though ridiculous thing," recalled Father Benavides as if he had seen it himself,

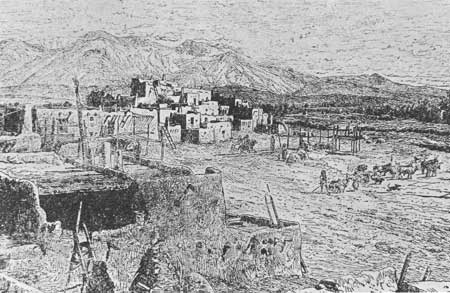

Overnight, the open grassy valley that spread out to the east and southeast of the church door was transformed into an Apache rendezvous with clusters of conical skin tipis, running children, yapping dogs, and the smoke of a hundred fires. One of Oñate's men who had explored east from Pecos in 1598 left a graphic portrayal of these dog-nomads and their tipis as he saw them on the plains, where he

Items of Trade Trade between Apaches and Pecos had developed in the sixteenth century soon after the nomads adapted themselves to the buffalo plains. From mid-century on, volume picked up, as evidenced by the increasing number of plains artifacts—Alibates flint knives, flint and bone scrapers, and bone hide-painting tools—found at datable levels by archaeologists at Pecos. Because of the near absence of such items in the Tano pueblos to the west, A. V. Kidder concluded that the Pecos "may have been more or less monopolistic middlemen for the westward diffusion" of plains goods. [52] The nomads brought mainly products of the buffalo—hides and leather goods, jerked or powdered meat, and tallow. They also brought tanned skins of other animals, antelope, deer, and elk; flint and bone tools; salt; and on occasion captives of the "Quivira nation," their Caddoan-speaking neighbors to the east. In return, the Pecos gave them maize and other agricultural produce, as well as incidental goods available in the pueblos—painted cotton blankets, pottery, and local turquoise. When harvests were bad and the Pueblos had no surplus to trade, the hungry nomads sometimes fell back on raiding.

Spaniards Intrude In a land as poor as New Mexico, it is no wonder that the invaders sought to profit from the established Pecos-Apache trade. By 1622, Fray Andrés Juárez recognized that the items packed in by the dog-nomads were "very important both to the natives and to the Spaniards." [53] Both relied on the skins for clothing. In addition, said Benavides, the colonists acquired them "for use as sacks, tents, cuirasses, footwear, and everything else imaginable." To dress a skin, the Plains women scraped the rawhide, rubbed in an oily mixture of fat and brains, dried it, then worked it to make it pliable. Smoking rendered it moisture resistant. On some of the buffalo hides meant for use as winter robes, they left the hair; others they scraped thin and tanned until soft as velvet. Such hides and skins became regular items of tribute exacted from the Pecos by their encomendero. [54] The demands of the Spaniards and the articles they offered for barter—most notably the ubiquitous iron trade knife and later the horse—won a large share of the trade away from the Pecos. Although Coronado found Plains Indian captives living at Pecos as "slaves," the slave trade did not quicken until the Spaniards came to stay. After that, the demand grew so insatiable that Spanish slaving raids directed at the Apaches themselves periodically threatened to wreck the peaceful trade fairs at Pecos and other frontier pueblos. Still, most years they came. When they did, "the friars always talked to them of God." On one occasion, to hear Father Benavides tell it, certain captains of the Vaquero Apaches entered Santa Fe to see for themselves the famous image of the Assumption of Our Lady which the custos had brought to New Mexico. "The first time they saw it was at night, surrounded by many lighted candles, and there was music. It would be a long matter to relate all my conversations with these captains about their learning how to become Christians." The blandishments worked. The Vaqueros agreed to "a large settlement on a site chosen by them." Just then the devil interfered. [55] Eager to profit in the slave trade, a successor of the infamous Juan de Eulate, almost certainly don Felipe de Sotelo Osorio, sent out a strong party of Indians to collect as many captives as they could. On the plains, they came upon the Vaqueros who had just vowed before the image of Our Lady to become Christians. The eager slavers attacked, killed the chief, and returned with some of the others. Stung by the friars' outcry, the governor reneged and condemned the deed as foul. But the damage had been done. [56] Father Juárez also worked on the Vaqueros. Not content to sit back and wait for their annual visit to Pecos, he ventured out onto the plains himself, apparently in the company of Spanish traders. He was probably with Capt. Alonso Baca in 1634. Baca and party pressed due east "almost three hundred leagues" to the Arkansas River. There "the friendly Indians who accompanied him," Apaches no doubt, refused to let the Spaniards cross over into Caddoan Quivira. [57] A generation later, evidently referring to this 1634 expedition, a defendant before the Inquisition admitted that he had gone out on the plains because he wanted the Apaches to make him a captain "as they had done with Capt. Antonio [Alonso] Baca, Francisco Luján, and Gaspar Pérez, father of the one who confesses, and with a friar of the Order of St. Francis named Fray Andrés Juárez." Pérez, an armorer from Brussels who could make trade knives, reportedly "left a son" among the nomads. As part of the elaborate native ceremonial, the Spaniards were supposed to sleep with Apache maidens. [58] Father Juárez, never at a loss for words, this time may have resorted to sign language in defense of his chastity. Missionary Expansion of Benavides During the triennium of Alonso de Benavides, 1626-1629, the Franciscans had things pretty much their own way. Their old nemesis Juan de Eulate, relieved in December 1625 by Admiral Felipe de Sotelo Osorio, departed the colony the following autumn with the returning supply caravan. He had not changed. Soon after he reached Mexico City, he was arrested by civil authorities on charges that he had transported Indian slaves to New Spain for sale and that he had sequestered several of the wagons to haul merchandise duty free. Fined and made to pay the cost of shipping the slaves back to New Mexico, don Juan went free. In fact, he turned up later as governor of Margarita, an island off the Spanish Main. The enduring Fray Esteban de Perea, given leave at last to report in person to his superiors in Mexico City, rode the same caravan as Eulate, his arch adversary. He clutched a packet of documents, the sworn testimony of more than thirty persons heard by Father Benavides sitting as agent of the Inquisition. Still, he would not have the pleasure of seeing the ex-governor do public penance. Even though the Franciscans and the inquisitors accepted his damning reports with thanks, for some reason the Holy Office chose not to prosecute. For his pains, Fray Esteban was reelected custos of New Mexico. [59] While Perea immersed himself in the business of recruiting thirty more missionaries, the largest contingent ever, and in preparations for the next supply train north, Benavides threw himself into expansion with a vengeance. He had brought a dozen friars himself. He could have used four times as many. Operating in all directions from his residence at Santo Domingo, the hardy prelate carried the gospel himself to the Piros in the Socorro area and to the Tompiros east of there. He utilized well what men he had, both veterans and beginners, thrusting new missions into three Tano and Southern Tiwa pueblos and renewing work at Taos, Picurís, and among the Jémez. He tried also, by pursuing their leaders, to convert the nomads who surrounded the colony "on all sides." Miracles or no miracles, with them he failed. [60] Fray Pedro de Ortega among the Nomads One of the men Custos Benavides relied on for missionary outreach to the nomads was Pedro de Ortega, formerly of Galisteo, Pecos, and Taos. In 1625, after three trying years with the Taos, Fray Pedro had accepted reassignment to Santa Fe as guardian of the convento and teacher of the boys in the capital, both Spanish and Indian. When Benavides arrived, he appointed Ortega notary of the Inquisition, to serve "with all fidelity, legality, and secrecy." At the stately service of welcome and institution of the new prelate, it was Ortega who rose after the gospel and, flanked by Sargento mayor Francisco Gómez holding the standard of the Holy Office and by the chief constable, read "in loud and intelligible voice" the first formal edict of the faith. It was the feast of Saint Paul's Conversion, January 25, 1625. The Inquisition had come to New Mexico. [61] While still at Taos, Father Ortega had heard of an Apache called Quinía "very famous in that country, very belligerent and valiant in war." His people, possibly an an cestral band of the Jicarillas, or perhaps Navajos, ranged the mountains north of Taos both east and west of the Rio Grande. Ortega had tried to convert Captain Quinia. Because the chief was so inclined, claims Benavides, a rival shot him in the chest with an arrow. Ortega and Brother Jerónimo de Pedraza, "a fine surgeon," hastened to Quinia's side and cured him, not with a scalpel but with a religious medal. For what it was worth in gifts and attentions, Quinia had kept in touch with the friars. He had begged Father Benavides for baptism. "To console him," wrote the custos, "I went to his rancherias . . . and planted there the first crosses. In the year 1628, Father fray Pedro de Ortega baptized him and another famous captain called Manases, who lived near his rancheria. At the time of their baptism, remarkable incidents occurred." [62] But Benavides, who had stirred up more demand for missionaries than he could supply, had no one to assign. The following spring, like manna, reinforcements appeared. The Return of Perea Esteban de Perea, custos elect since September 1627, had returned to New Mexico with a flock of twenty-nine friars. One had died en route. At chapter meeting, held on or about Pentecost 1629, he established priorities and made assignments. Most of the Piros and Tompiros, for lack of ministers, still had not been baptized. Perea now allotted six priests and two lay brothers to the task. Two more priests he appointed to the Apaches of Quinia and Manases. "And since it was the first entrada to that bellicose nation of warriors," the new governor don Francisco Manuel de Silva Nieto and a body of armed citizens went along. [63] At one of the Apaches' rancherias, they laid up in a single day "a church of logs, which they hewed; and they plastered these walls on the outside." Franciscans and royal governor, in an exemplary show of cooperation, both dirtied their hands in the work. But no sooner had Silva and the soldiers left than "the devil perverted Captain Quinia." The Indian disavowed his baptism and tried to kill one of the missionaries. Then he and his people moved on. Left alone in the woods, the friars had no choice but to abandon the place. [64] María de Ágreda and the End of Ortega A hundred leagues east of Santa Fe and more, beyond the Vaquero Apaches, lived another plains people called the Jumanos, a people who tattooed or painted their faces. The "miraculous conversion" of these "striped" Indians produced superb grist for Benavides' propaganda mill. One way or another, it killed Fray Pedro de Ortega. Some of the Jumanos on trading visits to the pueblos had developed a special relationship with Fray Juan de Salas of Isleta. Repeatedly they had begged him to return with them and baptize their people. Repeatedly he put them off. Then suddenly, with the arrival of the 1629 caravan, there was an abundance of missionaries, as well as a compelling reason to convert the Jumanos. At chapter, Custos Perea had read a letter from the archbishop of Mexico concerning the remarkable case of a Spanish conceptionist Franciscan nun called María de Jesús of Ágreda. Beginning in about 1620, God had miraculously transported her to New Mexico time and again to preach His word to the neglected heathens. The archbishop wanted the friars of New Mexico to investigate the claims "so that they may be verified in legal form." Was it not extraordinary, asked Benavides, that the Jumanos came so regularly every summer begging for baptism? It was as if some person had instilled in them this craving. When questioned that summer, the Jumanos pointed to a portrait of a nun.

What more could an apostle ask? Fray Juan de Salas and a companion joined the Jumanos on their return to the plains. After they had traveled more than a hundred leagues, exulted Benavides, a multitude "came out to receive them in procession, carrying a large cross and garlands of flowers." The nun, they said, had shown them how to process and had helped them decorate the cross. So many clamored for baptism that the two friars decided to go back and enlist help. As they prepared to take their leave they blessed the sick, more than two hundred, who "immediately arose, well and healed." [65]

At the same time, it would seem, another apostolic pair and their native interpreters were following a more northerly path that brought them "within view of the kingdom of Quivira." Despite "great dangers and sufferings," they preached and planted crosses at every turn. Then they too headed back to report all they had seen. This party was led by Pecos veteran Fray Pedro de Ortega, who by now had begun to see himself as an apostle of the plains. [66] Ortega begged to go again. Probably in 1632, probably with Fray Juan de Salas—the accounts vary—Ortega went out to the Jumano settlements, probably on the Río Colorado of present Texas. Although his companion soon returned to the Rio Grande, Fray Pedro stuck it out for six months. He worked hard preaching and catechizing, and he suffered much. According to Benavides' 1634 Memorial, Ortega worked himself to death among heathens and therefore deserved the title of martyr. Writing elsewhere, the same author made the missionary's death among the Jumanos a more conventional martyrdom: "on account of the great zeal of this conversion and because of the suspicion of those idolatrous Indians, they poisoned him with the most cruel poison." [67] Whether of fatigue or poison, Fray Pedro de Ortega, who had broken up idols at Pecos and had courted Quinía's Apaches, was dead. Except for the exaggerated propaganda of Benavides, so too were missions for the nomads, at least for the time being.

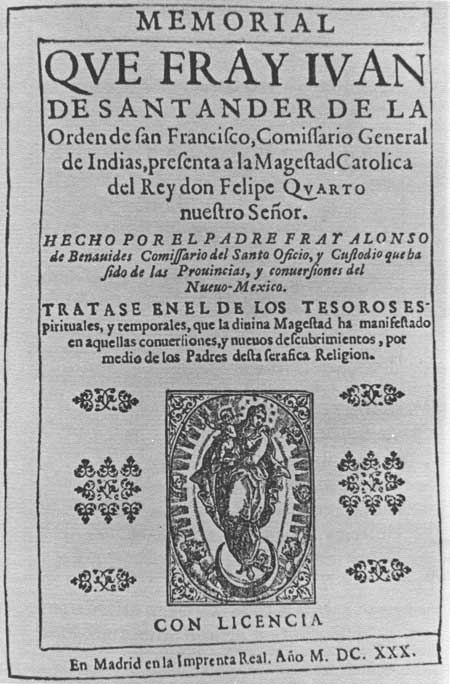

Missionaries to Ácoma, Zuñi, and Hopi In the summer of 1629, Custos Esteban de Perea led a missionary assault on the western pueblos. With Governor Silva, soldiers, ten wagons, and a large remuda, the prelate and eight or ten religious set out for Ácoma on the eve of St. John's Day. One dauntless missionary stayed atop the rock. At Hawikuh, three more chose to abide with the Zuñis, After the first Mass, the ritual act of possession in the name of pope and king, the salvo of arquebuses, the tilting, and the caracoling, governor and custos headed back to Santa Fe while another three friars, with an escort of a dozen soldiers, girded up their loins and pressed on to the Hopis. Meanwhile, Fray Alonso de Benavides, who remained in New Mexico awaiting the southbound caravan, kept himself busy founding a mission at Santa Clara, his tenth by his own count. Because Custos Perea's commission as agent of the Holy Office had not yet arrived, Benavides continued in that capacity. The Tewas of Santa Clara obliged him by painting the Inquisition's coat of arms in the new church, because "they did not wish any other church to have it." [68] Benavides as Lobbyist When finally he did take his leave in the fall of 1629, Benavides vowed he would return. He never did. Ironically, his influence on the missions of New Mexico increased after his departure. He became a lobbyist. Dispatched by his superiors to the court of Philip IV, the amiable and aspiring religious took to the assignment with gusto. Amid the perfume and lace, the lavish display and the notables of the realm, certain of whom had already sat for the gifted young court painter Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez, Fray Alonso inhaled the greatness of Spain. Surely His Most Catholic Majesty, once he was informed of New Mexico's "treasures" and of the "many marvels and miracles" that had illuminated the Franciscans' apostolate in that distant land, surely he would want to increase his support. Why should New Mexico not be created a diocese of the church? And why should he, Alonso de Benavides, not be consecrated its first bishop? His Memorial of 1630, printed at Madrid by royal authority, took the court by storm. The king read it. The council read it. "They liked it so well," wrote Benavides to the friars in New Mexico, "that not only did they read it many times and learn it by heart, but they have repeatedly asked me for other copies." Benavides Meets María de Ágreda In the spring of 1631, Fray Alonso traveled north from the Spanish court for an interview with the Reverend Mother María de Jesús, abbess of the convento of La Purísima Concepción in Ágreda. He carried an order from the Franciscan Father General constraining the nun to tell him everything she knew about New Mexico. Prodded by her confessor and the Father Provincial, she did. In answer to Benavides' leading questions, she gave detailed descriptions of some of the New Mexico friars she had seen on her "flights," including Father Ortega. So many features of the countryside did she recall, even some Benavides had forgotten, that, in his words, "she brought them back to my mind." In his mind, the enraptured friar embellished everything the young abbess said. He begged her to write a letter in her own hand proclaiming God's special concern for the Franciscan missionaries of New Mexico. It made grand publicity. [69]

The Mission Supply Contract of 1631 While Benavides advertised the missions of New Mexico in Europe at the expense of a sensitive and confused nun, the superiors of his province negotiated a financial agreement with royal officials. This contract, signed in Mexico City on April 30, 1631—the day before Fray Alonso reached Ágreda—spelled out to the last fraction of a peso the amount the crown was willing to spend on these missions. For each item, the negotiators had arrived at a set figure: maintenance of a missionary in the field for the three years between supply caravans (450 pesos for a priest, 300 for a lay brother), outfitting a new missionary (875 pesos), travel expenses for each friar (325), cost of each wagon and its sixteen mules (374 pesos, 4 tomines). The Franciscans assumed the upkeep of the wagons and replacement of spent mules; the crown provided the military escort. By adding the twenty friars being sent out in 1631 to the forty-six already in the field, treasury officials came up with a ceiling on the number of missionaries the crown would subsidize in New Mexico, sixty-six. Only in the late 1650s was the ceiling lifted with the addition of four more for the El Paso district.

For thirty-three years the contract stood. It converted mission supply into a business-like and efficient operation. Instead of providing the friars with supplies in kind as before, the treasury now turned over to the procurator-general of the custody a lump sum for the sixty-six missionaries. Everything else was up to the Franciscans. Thanks largely to one remarkable man, Procurator-general fray Tomás Manso, later bishop of Nicaragua, the system ran smoothly and on schedule. Making the arduous round trip with the wagons probably nine times, Manso kept his finger on every detail. The 1631 contract called for thirty-two wagons, one for every two New Mexico missionaries, excepting the procurator-general and his assistant. These were not the quaint two-wheeled ox carts of the Castaño de Sosa entrada. They were heavy, four-wheeled freight wagons with iron tires, drawn by a team of eight mules, and capable of hauling two tons. On the road, the long train was divided into two squadrons of sixteen wagons, each squadron under the whip of a wagon master. To set them apart, the two lead wagons, like flagships, flew banners displaying the royal coat of arms and their teams were specially caparisoned and wore bells. The squadrons were further broken down into eight-wagon divisions whose lead wagons also flew the royal banner.

The round trip took a year and a half more or less, six months out, six months in New Mexico, and six months back. That left the procurator-general eighteen months to organize and outfit the next northbound train. As long as Father Manso ran the supply service, neither treasury officials nor missionaries could find much to complain about.

In practice, the triennial caravan was more than a mission supply service. It was New Mexico's lifeline, the only regularly scheduled freight, mail, and passenger service between the colony and points south. Outbound, royal wagons and Franciscans on muleback, attended by military escort, hundreds of spare mules, and meat on the hoof, were joined by everyone else going to New Mexico, from royal governor to merchants to penniless hangers-on. It was a motley, boisterous train. On the way back, a similar conglomeration formed around the king's wagons. Governors and ex-governors, claiming the right to use the emptied wagons for shipment of hides, salt, piñon nuts, and other produce of the province, wrangled with the friars who saw these exports as fruits of the unlawful exploitation of Indians. Missionary control of the wagons added yet another dimension to conflict between church and state. [70]

Missionary Reverses By the early 1630s, the Franciscans had all but covered the Pueblo world. From Pecos to Oraibi, from Senecú to Taos, resident missionaries sought to impose the Christian regime described by Fray Alonso de Benavides. Opposition by traditional Pueblo leaders, veiled in most of the communities, erupted violently in the western pueblos, those farthest from the seat of Spanish authority. At Hawikuh on February 22, 1632, the Zuñis put Fray Francisco de Letrado to death and danced with his scalp on a pole. Five days later they caught up with Fray Martín de Arvide, who had set out in search of the Opata and Pima Indians of Sonora, and killed him too. At the Hopi pueblo of Awátovi, the following year, alleged miracle worker Fray Francisco de Porras died a painful martyr's death when he ate food poisoned by "the priests of the idols." About the same time, the friars pulled back from the Tompiros of Las Humanas and the Jémez of Giusewa, presumably out of fear and frustration. Disappearance of Alonso de Benavides The news from New Mexico reached Father Benavides at Rome in time for him to include accounts of these "glorious deaths" in the revised memorial he was preparing for Pope Urban VIII. In every way he knew how, the resourceful Fray Alonso continued to promote the New Mexico missions. His fond hope of becoming the first bishop of Santa Fe seemed at times within his grasp. In 1635, back at the Spanish court, he arranged for return passage to the Indies. Then, when the proposal to make New Mexico a bishopric ran into bureaucratic snags, Benavides, the colony's premier propagandist of the seventeenth century, accepted appointment as auxiliary bishop of Goa in Portuguese India. He left for Lisbon at once. Since his name does not appear on any of the standard lists of bishops, it is possible that he died on the outward voyage. It was as if he had sailed off the end of the earth. [71]