Contents Foreword Preface Jesuit Foundations Gray Robes for Black 1767-68 The Archreformer Backs Down 1768-72 Tumacácori or Troy? 1772-74 The Course of Empire 1774-76 The Promise and Default of the Provincias Internas 1776-81 The Challenge of a Reforming Bishop 1781-95 A Quarrel Among Friars 1795-1808 "Corruption Has Come Among Us" 1808-20 A Trampled Guarantee 1820-28 Hanging On 1828-56 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

LIKE SAINT PAUL, the gray-robed Franciscans of the missionary college in Querétaro craved to preach to gentiles, to proclaim the good news to perfect strangers. If at times more risky than daily tending the tares that grew up in a congregation of "the faithful," it also was more satisfying and closer to the apostolic tradition of the Church. The friars wanted to be apostles in their own right. Pimería Alta, an unsolicited inheritance from the Jesuits, lay on the farthest northern frontier of Sonora, bounded on three sides by heathen tribes, but already beset by woes that had blunted the blackrobes' conquering momentum. The Franciscians looked upon it through new eyes. They saw it as a jumping-off place from which to carry the gospel to thousands of Indians who had never heard the name of Christ. Their own apostle, Fray Francisco Garcés, ranged farther west, north, and east than had the Jesuits' Father Kino. But of the four adulterated mission outposts the Queretarans were permitted to found, defiant Seris and Yumas quickly consumed three, and the fourth passed to the Franciscan province of Jalisco. Time after time the friars appealed for financial and military aid to expand their ministry. Time after time they proposed to establish missions in the harsh desert Papagueria and on the banks of the Río Gila. But never was there a compelling enough reason for the defense-minded empire to thrust another salient into the teeth of the hostile, seminomadic Apaches. Had Russians or Englishmen opened a road through the Pacific Northwest and dropped down the backside of the Sierra Nevada to the Colorado River, they might have provoked an aggressive response. As it was, the government, the military, and the church merely held the line. When finally the last two Queretaran missionaries withdrew from Pimería Alta in 1842—after a ministry of seventy-five years—they left behind not a single new mission. Through no lack of zeal on their part, the friars had been forced to preserve and endure a secondhand apostolate, to build on other men's foundations. When the Jesuit Eusebio Francisco Kino, a muscular, wavy-haired Tyrolean with the intensity of Saint Paul, approached the Pima ranchería of Tumacácori with his entourage one day in January, 1691, he rode the tide of a century. From small beginnings and the first martyrdom in Sinaloa five hundred miles to the south and one hundred years before, the Jesuits had built a missionary empire that straddled the Sierra Madre Occidental and welled up New Spain's west coast corridor. They had reaped tens of thousands of baptisms, among the Tehuecos, Zuaques, Sinaloas, Acaxee, Chínapas, Tepecanos, Tepehuanes, Tarahumaras, Mayos, Yaquis, Pimas Bajos, and Ópatas. They had made themselves the most powerful social and economic corporation in a vast region. But the tide would carry them no farther north than Pimería Alta. [1]

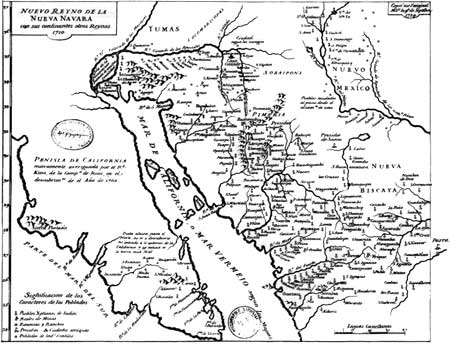

On maps the homeland of the Upper Pima Indians came into focus more or less with the Magdalena and Altar River valleys in the south, the Gulf of California and the Yumas in the west, the valley of the Gila and the Apaches in the north, and the San Pedro Valley and the Apaches in the east, fifty thousand square miles. Historically the province of Sonora's northernmost district, Pimería Alta has been artificially divided since the 1850s by the international border separating the Mexican state of Sonora from Arizona. It is arid and semiarid basin-and-range country, where the temperature exceeds a hundred degrees in the summer and drops below freezing in the winter, where localized rains fall mostly from July to September, with occasional widespread but less dependable cold winter rains and now and again a light blanket of snow. [2] There may have been thirty thousand Pimas Altos. They all spoke dialects of a common language. Culturally they differed considerably, from irrigation farmers to nomadic gatherers. Though the Spaniards would from time to time exalt a native leader as "captain general of the Pima nation," they recognized that no such tribal polity existed. The "river Pimas" lived along the more dependable water courses in rancherías of related families. The word ranchería applied to both people and place, to both the community and the cluster of dome-shaped brush-and-earth houses in which they lived. The river Pimas irrigated maize, squash, and beans but relied at least as much on wild foods and the hunt. Though the people of several rancherías did on occasion join together for ceremonials, games, or a war party, most of the time they acted independently. Certain of these relatively permanent rancherías Father Kino designated mission sites. With the addition of an adobe church and quarters for the missionary, a native ranchería became a mission pueblo, or town, an uplifting designation that implied progress toward hispanic civilization. But like wearing long pants, it did not change the "uncivilized mission child" into a man overnight. Acculturation was a gradual process, painfully so in distant, beleaguered Pimería Alta where for decades missions remained in fact more ranchería than pueblo. Most of the missions "founded" by Kino—with such notable exceptions as Dolores, Remedios, Soamca, and Sonoita of the west—survived a century and a half by contracting and by bringing in new blood. As it worked out, the less stable desert-dwelling Pimas, whom the Spaniards called Pápagos, provided a reserve to be drawn into the missions as the river Pimas died off. [3] Between 1687 and 1711 Kino dominated the Jesuit effort in Pimería Alta. An individual of great energy, toughness, and appeal, he created widespread demand among the natives for the material benefits of Christianity. As he explored and mapped their country, he doled out trinkets, tools, seed, and livestock, preached, and encouraged them to build with adobe. He did not press them to give up their old ways, their dancing and ceremonial drinking, their medicine men and curing rites. They responded willingly when he asked them to plant and build. They offered their children for baptism. They joined campaigns against Apaches. With Father Kino it was Christianity on their terms, plenty of benefits and few demands. At the same time, the astute Jesuit politician and propagandist beat down the opposition of frontier entrepreneurs who wanted the Pimas, on the basis of their alleged prior depredations and bad character, to be classed with the Apaches as enemies of the province. Rancher, farmer, and miner coveted Pima labor and Pima lands. Kino, by representing these natives as loyal, industrious, and eager to receive the faith, by baptizing goodly numbers of them, won official sanction for the Jesuits' Pima ministry. Though local opponents over and over raised the cry for secularization, the missionary frontier defined by Kino endured for generations. Both sides, for and against the missions, invoked the law. Not in Pimería Alta or anywhere else was the mission meant to last forever. Once it had served its Christianizing and hispanicizing function it was to yield to secularization, the process by which a parish priest of the secular clergy—a preserver of the faith—replaced the religious of the regular clergy—the propagator of the faith—by which the mission properties were divided among the Indians, and by which these former wards of the missionary became tax-paying citizens of the empire. The missionary was to move on, to roll back farther and farther, the pall of heathendom.

Under the law newly conquered Indians were exempt from paying tribute for ten years. By a loose interpretation opponents of the missions called for secularization at ten years. The missionaries, protesting that their charges were not yet ready, spoke of the intent of the law and cited a whole corpus of legislation to underscore their Christian obligation to the native American. In a place like Pimería Alta, where poverty and hostilities deterred the secular clergy, the missionary won by default. Not all the Jesuits who joined or followed Kino shared the apostle's favorable opinion of the Pimas. When a missionary moved in with them and began treating them as wards day in and day out, making them work when they would rather not, suppressing their ceremonials, and deriding their medicine men as witches, he understandably provoked their resentment. In 1695 the Pimas of the Altar Valley rebelled and in the course of their frenzy put to death a young missionary. The resourceful Kino, taking as his text Tertullian's "the blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church," turned the event into a triumph of propaganda. [4] In time Jesuit Pimería Alta came to comprise eight missions, each with its cabecera, the head pueblo and missionary's residence, and its several dependent visitas. The total number of Pimas Altos living in mission pueblos probably never exceeded four to five thousand. In 1751 the natives of the Altar Valley rose up again, killing two Jesuits and a hundred others. But except during the uneasy decade of the 1750s the majority of mission Indians found more reason to stay on—an attachment to place and kin, a relatively dependable food supply, protection, the fear of punishment, or the working of the Holy Spirit—than to flee. [5] During the last decade the Jesuits barely hung on. The thin line of settlement in the Santa Cruz Valley threatened to break under the strain of Apache hostility. Before 1762 the Pimas living to the east in the parallel San Pedro Valley had absorbed some of the blows. But that year the Sobáipuris, who had refused earlier to accept resident missionaries, let the Spaniards evacuate them to the Santa Cruz Valley missions, purportedly to strengthen those establishments. That left the San Pedro deserted, "an open door" for the Apaches. Soon after, the harassed settlers living along the fertile big bend of the Santa Cruz fled their homes. "Hispanic Arizona" was reduced to the mission and moribund pueblo of Guevavi, ten miles northeast of present-day Nogales, its three visitas, Calabazas, Sonoita, and Tumacácori; the fifty-man presidial garrison at Tubac, founded in the wake of the 1751 uprising; and "heathen and isolated" San Xavier del Bac with its visita Tucson, "farthest Christian pueblo." Father Custodio Ximeno, a tall and swarthy Spaniard with a big nose, wanted to abandon "baneful Guevavi." He had suffered malarial fever. He had seen his Indians dying in epidemics. He buried more of them than he baptized. Apaches drove off his stock. By 1766 only fifty Pimas and Pápagos were left at Guevavi. Father Custodio thought of moving to more populous Tumacácori, fifteen miles north, almost within shouting distance of the Tubac company. But his superior refused to let him forsake Guevavi, suggesting instead that the mission be split in two, that both Guevavi and Tumacácori be cabeceras. Nothing came of either proposal. Instead, when a replacement for San Xavier failed to arrive, Custodio Ximeno found himself responsible for the whole valley from Guevavi to Tucson. But by then time had run out for the blackrobes. [6] In the twenty-nine-year reign of Charles III (1759-88), Spain and the Enlightenment commingled. The result was an unprecedented climate of reform in which the king and his ministers took the initiative for the good of the Spanish people. Guided by a high sense of duty and convinced that absolute control was a prerequisite of reform, Charles eliminated checks on the royal power. Through a more efficient and centralized professional bureaucracy he drew the Spanish nation closer together politically than it had ever been and at the same time stimulated the economy. A devout and morally unassailable Catholic, he took it as his royal duty to limit clerical immunities and to subordinate and reform the church in his realms. In the missions of Pimería Alta that meant the end of the Jesuits and a constant struggle for the Franciscans. By expelling the influential, ultramontane Society of Jesús from Spain and the empire, Charles III moved a step closer to royal control over the church. He followed with measures designed to subordinate the universities and the Inquisition. By appointing able and loyal prelates, he both raised the quality of the Spanish episcopate and drew it closer to the crown. He attacked the "abuses" of the regular clergy and sought to reduce their numbers while restoring their discipline. In this climate of reform, and in the increasingly secular, even anti-clerical age that followed, ministers of the king listened seriously to proposals for emasculating or abolishing the missions. In addition to all the old woes—restive neophytes, Apache hostility, disease and dwindling native population, encroaching settlers, and lack of government support—the friars on the Sonora frontier labored in the shadow of the reformers, a shadow that threatened to eclipse the mission as an institution. [7] The missionary in New Spain had enjoyed notable autonomy. From the beginning the popes, recognizing the immensity of the task, granted to the missionizing orders the rights and prerogatives of parish priests and the authority to administer the sacraments. Naturally the secular clergy resented the regulars' pontifical privileges and hastened to point out the missionaries' abuses, some well documented. Passionately, and with considerable success, the missionaries resisted encroachment and held on to their spiritual autonomy. In addition they fought for economic and political autonomy. Their ideal was an absolute paternalism within the missions. Unless a missionary could provide materially for his Indians and discipline them with authority, he stood little chance of converting them. [8] In 1767 the reformers tried to throw out the traditional paternalism along with the Jesuits. They would grant the Indians civil rights and put mission economics in the hands of government agents. The new missionaries protested vehemently that their hands were tied. They begged that the old system be restored, carefully pointing to the success of their Franciscan brothers in Texas rather than to that of the discredited Jesuits. Faced by the rapid deterioration of the missions, the reformers relented. But only after the death of Charles III could it be openly admitted that the blackrobes, pursuing the traditional autonomy of missionaries in New Spain, had made their missions flourish. The friars wanted no less. When they arrived in Pimería Alta, the Franciscans found the eighty-year-old Jesuit foundations crumbling. They buttressed them and built upon them. [9] They endured for seventy-five more years, under the most adverse conditions. Yet because the Jesuits were the pioneers, the original builders, and the Franciscans replacements; because the dramatic reforms of Charles III and the events leading to Mexican independence overshadowed their efforts; and because Jesuit chronicles have been generally more accessible than Franciscan, the friars have come off a poor second. Scholars have shown a tendency to skip lightly over the Franciscan years, tipping their hats only to the explorer Garcés, or they have been led to make undue comparisons. [10] Actually, many more Franciscans than Jesuits served in Pimería Alta. They used largely the same methods as their predecessors, and they fought just as hard to maintain their autonomy. Their zeal was no less intense, no less praiseworthy or damnable. As a group they were no less observant than the Jesuits, no less strict, no less devoted to their charges, no less likely—at least at mid-century—to know the Piman language. [11] These qualities depended on the individual and the circumstances, not on the color of his habit or the personality of the order's founder. The differences counted for little: the Jesuits came from all parts of Europe, the Franciscans from Spain or Spanish America; the Jesuits called their superior in the field a rector, the Franciscans a president; the Jesuits emphasized certain devotions, the Franciscans others. The friars had no choice. For two more generations, for better or for worse, they prolonged the Sonora mission frontier. They had to build on Jesuit foundations, and build they did. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||