Contents Foreword Preface Jesuit Foundations Gray Robes for Black 1767-68 The Archreformer Backs Down 1768-72 Tumacácori or Troy? 1772-74 The Course of Empire 1774-76 The Promise and Default of the Provincias Internas 1776-81 The Challenge of a Reforming Bishop 1781-95 A Quarrel Among Friars 1795-1808 "Corruption Has Come Among Us" 1808-20 A Trampled Guarantee 1820-28 Hanging On 1828-56 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

HAD NARCISO GUTIÉRREZ LIVED three weeks longer he would have met the bishop. Fray Bernardo del Espíritu Santo, peninsular Spaniard, Carmelite, and former confessor to a viceroy, had vowed to carry "his first, holy, and general visitation" to the farthest reaches of his diocese, in Sonora all the way to the Santa Cruz Valley, to Tumacácori, Tubac, and Tucson, where none of his predecessors had ever ventured. In the teeth of driving dust, despite axle-deep mud, rain, torrid heat, and bitter cold, and nearly a year on the road, Bernardo, Bishop of Sonora, did come. Convoyed by armed riders, the bishop's entourage proceeded slowly down the valley late in December, 1820. From the mines of Guevavi, the rancho of Calabazas, and the other clusters of adobe jacales up and down the river, parents brought their children for confirmation. As he laid his right hand on the head of each the sixty-one-year-old prelate intoned in Latin "I sign thee with the sign of the cross and I confirm thee with the chrism of salvation, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit." On this visitation alone, the bishop would travel over three thousand miles and confirm an estimated sixty thousand persons. [1] At Tumacácori a tall, slender, newly arrived friar, rather swarthy, with black hair, black eyes, and a mallorquin accent, received the bishop on New Year's Day, 1821. He presented the mission books of administration for the prelate's inspection. Two burial entries left unsigned since mid-November, when Father Narciso had been too weak even to write his name, Bishop Bernardo ordered signed. His secretary then inscribed formal notice of the episcopal visitation. Not until later did someone write a terse, unnumbered entry recording the death of Narciso Gutiérrez "on December 13, 1821," an error for 1820. Again, in his uneven scrawl, the new friar signed. [2] Father Narciso would not have approved of his successor. The erratic Juan Bautista Estelric, age thirty-six, was one of the "new ones," a member of the notorious mission of 1810-1813. He had been at Magdalena, visita of San Ignacio, since May of 1819. A couple of weeks after Gutiérrez died he took over at Tumacácori and Tubac. Born November 24, 1784, in the villa of Muro on the isle of Mallorca, Estelric had taken the holy habit of Saint Francis on February 21, 1801, in the convento of Santa María de los Ángeles de Jesús outside the walls of Palma. He had sailed for overseas missions from Cádiz in November 1812 aboard the frigate Veloz with three other recruits. Because of the insurrection in New Spain, they had been transshipped from Veracruz to the port of Altamira. From there they made their way overland to San Luis Potosí, where the leader of the little band, Fray Manuel Marín, comported himself like a soldier, which the others reported to Querétaro. From the moment they reached the college Marín moaned that he could not stand the place or the thought of a missionary's life. His behavior convinced Father Bringas that some of the new recruits had answered the call in Spain out of fear of French bayonets, not because of missionary zeal. [3]

Father Estelric took stock in a hurry. He noted that his mission had yielded during 1820 only 160 fanegas of wheat, 12 of maize, 16 of frijoles, no garbanzos and no lentils. Obviously his 121 Indians and 75 gente de razón could not subsist on that. Yet the mission still showed on the books 5,500 head of cattle—twenty-eight for every man, woman, and child—1,080 sheep, down considerably in the past few years, 590 horses, 60 mules, and 20 donkeys. [4] Therein roamed Tumacácori's potential wealth, if only a buyer could be found. Just then one appeared. Twenty-nine-year-old don Ignacio Pérez, a native of Arizpe, a frontier career officer, rancher, and entrepreneur, and son of the owner of the Cananea mines, had big plans. "He shows promise," said his military superiors, "because of his ready aptitude and talent." In December, 1820, he had applied for a grant to the sprawling San Bernardino ranch, a hundred miles east of Tumacácori. In his petition Pérez outlined his plans for converting the San Bernardino into a buffer zone between the Apaches and the northern settlements. It would complement the presidial cordon. He might even induce Apaches to farm some of his land. [5] But foremost in don Ignacio's mind was a cattle empire, as large as any in the province. To stock the San Bernardino he needed thousands of head. At Tumacácori, Pérez and Estelric struck a bargain. The contract, signed on January 2, 1821, the day after the bishop's visitation, called for the sale of 4,000 of the mission's cattle at three pesos a head, the proceeds to go toward completion of Gutiérrez' long-deferred church. Pérez agreed to pay four thousand pesos in cash upon receipt of the herd, two thousand more in six months, and the remaining six thousand within a year and a half. The friar set vaqueros to rounding up the half-wild stock. In February, Pérez' associate, don Rafael Elías González, reined up at Tumacácori. He had the money. Don Rafael, a rancher in his own right and later governor of Sonora, was a brother of Lieutenant Ignacio Elías González, now in residence at Tubac, and of Adjutant Inspector Simón Elías González, whom many remembered as one of the council of war that had sentenced Father Hidalgo to death in 1811. Father Estelric was dealing with the frontier ricos. As don Rafael's men headed up the herd the friar congratulated himself. In no more than a few weeks he had realized four thousand pesos. He held a contract with reputable persons for another eight thousand. Now he could get on with the building. [6] During the last years of Spanish rule in Mexico the racial makeup in and around the Pimería Alta missions was notably different from what it had been when the first Queretaran friars arrived a half-century before. There were far more gente de razón, and only half as many mission Indians. The Franciscans statistics for the eight missions and their visitas, not counting presidial communities, told the story:

Although the ratio of gente de razón to mission Indians at Tumacácori was on the rise, and in 1820 stood at three to five, only Tumacácori, San Xavier del Bac, and Caborca still claimed on their rolls more Indians than non-Indians. If the friars at Tumacácori and Bac counted their service as presidial chaplains, their ratios too were upset in favor of the gente. At the extreme, the missionaries of San Ignacio, where Father Estelric had served previously, found themselves in 1820 ministering to 1,471 "Spaniards and mixbreeds" and only 47 Indians, an adverse ratio of thirty-one to one! [7] Declining Indian population always vexed the missionaries. They had seen their charges dying off in epidemics and war or fleeing back to heathendom. Others they knew deserted to the mines and haciendas, became muleteers, or joined the army. In these ways they "civilized" themselves, transposing themselves in the statistics from indios to gente de razón, from the paternalistic care of the friar to the real world outside. Increasingly Pápagos took the places of the original Pimas in the missions, until, observed San Ignacio's Fray Joseph Pérez in 1817, there was hardly a legitimate Pima left. [8] The going and the coming in the missions of Pimería Alta lent weight to the friars' constant profession that their establishments were conversiones vivas, actively propagating the faith on a heathen frontier. It also explained in part why a century and more after Father Kino the missionaries still lamented their charges' spiritual backwardness, called them neophytes, and steadfastly opposed secularization. There were always more Pápagos. [9] Even had the times been tranquil, the influx of gente de razón into semi-arid Pimería Alta would have put mounting pressure on mission lands and water. In the turmoil of insurrection and independence non-Indians were bound to take advantage and move in. After the infamous Pimería Alta scandals of 1815 and 1816, the viceroy had implored the Father Guardian of the Querétaro college to assign as missionaries only the most exemplary, virtuous, and prudent friars. Unfortunately, Juan Bautista Estelric was none of these. Very soon his superiors had reports of his imprudence. Worse would follow. Apparently Estelric's chaplaincy at Tubac, where the bishop had personally bestowed the faculties upon him, began peacefully enough. He signed the burial entries for those who had died since November, 1820, including young Tomás Ojeda, killed the first week in December by Apaches at the mine called El Salero. [10] He married don Teodoro Ramírez of Tucson and Serafina Quijada of Tubac. Don Teodoro, son of Tumacácori's former interpreter, had just inherited the possessions of his godfather, Fray Pedro de Arriquibar, recently deceased chaplain of Tucson. And in February the tall, lank grayrobe officiated at the wedding of don Tomás Ortiz, heir with his brother to the Arivaca grant, and doña Joséfa Clementa Elías González, daughter of Commandant Ignacio Elías González. [11] Shortly thereafter, Estelric and Elías quarreled angrily. Don Ignacio, a Sonora criollo, formally denounced the Spanish-born friar to Father Prefect Francisco Núñez, the recruiter who had brought Estelric from Spain a decade earlier. Núñez reported the altercation to Fray Faustino González of Caborca. The balding González, chosen by the superiors as Father President after the death of Francisco Moyano in 1818, had served as secretary during the indictments against Creó, Fontbona, and Ruiz. He knew how damaging to the college another scandal could be. "Because of the illness of Father Estelric and his phlegmatic nature," the Father President resolved to go to Tumacácori himself. Appealing to their reason, he managed to calm their passions and reconcile the two men. That summer Bishop Espíritu Santo complimented him on his handling of the affair. "I greatly appreciate it and trust that no further discord will be aroused—it is so dangerous in these times." [12] The bishop was holding his breath. He and most of the Mexican hierarchy, along with the superiors of the regular clergy, fiercely opposed the anti-clerical measures issuing from the Spanish Cortes—attacks on the right of the church to own and acquire property, plans to suppress the religious orders, abolition of clerical immunity in criminal cases. Some of the prelates had joined with a cabal of the privileged, men of means and station, peninsulares and criollos, to insure their ruling position in an independent Mexico. This was reaction, not revolution. If all went well they planned to offer a Mexican throne to the abused Spanish king. On February 24, 1821, the conspirators' tool, a wily criollo officer named Agustín de Iturbide, proclaimed the seductive Plan de Iguala with its three guarantees—immediate and total independence, equality of criollo and peninsular, and defense of the one, true, and Catholic faith. The cry caught on. One after another, government officials, military barracks, and bishops, even the war-wearied old insurgents joined the chorus. Everywhere the people turned out to cheer the Army of the Three Guarantees. In late August, Commandant General Alejo García Conde, hero of Piaxtla, embraced the Plan of Iguala and decreed from Chihuahua that local authorities throughout the western Provincias Internas do likewise. At Tucson, Lieutenant Colonel Arvizu, who had also fought the rebels at Piaxtla, proclaimed his adherence on September 3. Three days later Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Narbona led the garrison of Arizpe in swearing the new allegiance. Intendant-Governor Antonio Cordero refused and resigned. At Cieneguilla, where enthusiastic royalists had burned Father Hidalgo in effigy a decade before, the president of the town council tried to modify the oath. The military convinced him otherwise. There was no stopping independence now. A full month after General Iturbide had reached an accord with the incoming Spanish viceroy, Bishop Espíritu Santo, a royalist at heart, formally acknowledged the success of the trigarante coalition. From his episcopal palace in Culiacan on September 27, the very day Iturbide rode triumphantly into Mexico City, the prelate of Sonora recommended to all his parishioners independence, equality, and religion. What that meant for the missionaries of Pimería Alta, they could only guess. [13] Amid the shouting, Pérez' second payment for the 4,000 Tumacácori cattle fell due. Father Estelric, who had construction crews back on the church job, was counting on the money for payroll and materials. When August 16, the due date, passed with no sign of the two thousand pesos, the friar applied to don Rafael Elías. When that brought no satisfaction Estelric wrote a one-thousand-peso draft on don Ignacio Pérez in favor of Félix Antonio Bustamante, citizen of Sombrerete, resident at Tumacácori, and likely the master builder. In a firm letter, which Pérez later described as so full of indignities he could hardly believe it, the missionary told the cattle buyer that if he failed to honor the draft on sight "I shall be forced to take other measures to recover the said sum and meet my obligations, steps that will be for me most painful but unavoidable." Pérez honored the draft. [14] The other one thousand pesos, which Estelric demanded be delivered at the mission immediately," Pérez sat on. Who could tell what effect independence would have on the missions, on Spanish currency, or on debts contracted with Spaniards before the Plan of Iguala. Sadly depressed, the "phlegmatic" friar all but gave up. His obligations and his conscience weighed too heavily. He was ill. He had sinned. By late January, 1822, when the mail brought another episcopal circular ordering public prayers for the well-being of independent México, Estelric was too weak to sign. Instead, the man with whom he had quarreled, Comandante Ignacio Elías of Tubac, signed for him. [15] Fray Francisco Núñez, the college's comisario prefecto, had observed Mexico's progress toward independence from Magdalena, where he had resided since the summer of 1821. The following spring with his secretary Fray Ramón Liberós, Núñez made his visitation of the missions, the first of the Mexican period. Arriving at Tumacácori during holy week, the comisario found the mission books in order but apparently little else. Father Estelric was still not well, work on the church had been suspended, and ugly rumors were circulating again. The three friars observed Easter Sunday, April 7, 1822. It was Liberós' birthday. Though Father Prefect Núñez left Estelric at Tumacácori and went on about his inspection, he had decided to remove him. Late in May, Ramón Liberós returned and took charge. Estelric had been told to report to Father President González at Caborca. In a less-than-honest letter to Bishop Espíritu Santo, González explained that Estelric had declared himself "unable to carry the burden of that mission because of his attacks." [16] The Father President was trying to suppress another scandal. The case of Juan Bautista Estelric involved more than physical illness. By early December it had reached such proportions that González felt obliged to inform the bishop fully, lest he learn about it from someone else. The Father Prefect had removed Estelric from Tumacácori on more serious grounds—"the scandal he was causing with a woman who attended him." At Caborca the Father President had permitted the seemingly repentant and sickly friar to live in the visita of Busanic. Secretly Estelric had the woman brought to him there. Still struggling to keep the affair quiet, Father Prefect Núñez simply ordered her returned to her parents. In response to other rumors that Estelric had embezzled assets belonging to Tumacácori, Father President González rode to that mission a second time to investigate. He turned up no irregularities. Next Estelric had called the Father President to confess him. He appeared moribund "or was pretending to be." After his confession the ex-missionary of Tumacácori defended his conduct with such detail and precision that he actually convinced González that he had been framed, that he was the victim of "malicious tongues." Filled with compassion for his maligned brother, the Father President offered to assign him as compañero at Cocóspera with spiritual responsibility for the Santa Cruz garrison. Within two days Estelric asked for the pass, saying that he would travel first to Pitic to consult a physician. Instead he went straight to Santa Cruz. Within a month the scandal was hotter than ever. Estelric had made a deal to have a woman brought to him for a price. Proceeding cautiously, Father President González verified that fact. There were further rumors of a couple of children. González put several friars on the case. They soon discovered that Estelric had stashed away in various places "in money, in gold and silver blanks, close to a thousand pesos, clothes, and superfluous things." As a temporary measure the Father President ordered the accused to retire to the mission of Sáric, there to abstain from saying Mass for twelve days and to do spiritual exercises. Instead he feigned illness and wrote to the bishop. [17] Shocked by such presumption, Bishop Espíritu Santo replied sternly. He would not under any circumstances contravene the decision of Father President González and award Estelric the chaplaincy at Santa Cruz. "Without doubt the conduct of Your Reverence is unbefitting the holy habit you wear and the apostolic ministry you exercise." [18] By November of 1824, the fall of Juan Bautista Estelric seemed complete. By "secret communique" a talebearing parish priest informed the bishop that Estelric "now has in his company his woman of the notorious scandals. He goes about without his habit, dressed like a layman." [19] Yet he survived. By affiliating himself with the Jalisco province he continued his ministry, such as it was, at Mátape, Horcasitas, Bacadéguachi, and lastly at Guásavas in east-central Sonora. Four years after most of his Spanish brethren had been exiled, Fray Juan Bautista contributed a horse and a fanega of wheat to a campaign against the Apaches. A priest to the end, Estelric died at Guasávas, suddenly and without sacraments. They buried him on December 29, 1835. He had just turned fifty-one. [20] No one pushed Ramón Liberós around. If don Ignacio Pérez hoped simply to forget his debt to the mission, he was in for a jolt. If don Ignacio Elías González thought he would have sport with the new friar from Spain, he misjudged his man. In Father Liberós, Tumacácori finally had a missionary to match the times. Thirty-three years old, tall, blue-eyed, with light complexion, sparse beard, and black hair, Fray Ramón looked like an aristocrat. He was from Aragón, born April 7, 1789, in the Villa de Mazaleón on the Río Matarraña. Though subject to the archbishop of Zaragoza, Mazaleón lay seventy miles southeast of that ancient city almost over into Catalonia, ancestral home of the Liberós family. Five weeks past Ramón's fifteenth birthday, the friars in the city of Calatayud received the devout lad into the order. Four years later French soldiers marched in the streets. Early in 1813 Father Liberós had traveled crosscountry to the Mediterranean port of Alicante, and from there booked a passage, which included thirty-one days in port because of stormy seas, south through the Straits to Cádiz. With Father Núñez and five others he had finally boarded the frigate San José alias El Comercio sailing July 16, 1813, the last and least troublesome contingent of that ill-starred mission. In Pimería Alta, Liberós became the neighbor of two of his former shipmates. The pock-marked valenciano Juan Vañó ministered at San Xavier del Bac. Late in 1820 after the demise of Father Arriquibar, he had been obliged to take over the presidio of Tucson as well. Unfortunately Vañó was not as tough as Liberós. At Cocóspera within a day's ride Fray Ramón had his friend Francisco Solano García, a cordobés, light-skinned with black hair and black eyes. [21] The debts, embezzlements, and sexual adventures of Juan Bautista Estelric put his successor at a disadvantage. He had to be above suspicion. With Father García as moral support Ramón Liberós took on Tumacácori and Tubac late in May of 1822. [22] He wasted no time.

Examining the papers in the mission archive, he came upon the cattle sale contract. He wrote immediately, addressing don Ignacio Pérez, a member of the Third Order of Saint Francis, as brother. "I greet you most warmly, and inform you that I am now in charge of this mission." He begged the would-be cattle baron to pay the overdue one thousand pesos at once and the remaining six thousand as soon as possible. "The mission," Liberós explained, "needs the money to continue its building program. It was for this reason that the cattle were sold." It was not that easy. For the next sixteen months the strong-minded Tumacácori friar dunned the wily debtor, countering his every ploy, till finally Pérez had to give up and sell part of his herd. Don Ignacio had tried selling Liberós blankets and sarapes at wholesale, had requested extensions because of alleged family and financial woes, had cajoled the friar's emissaries and had invited him to be patient until cattle prices rose. Fray Ramón would have none of it. While Pérez stalled, and was promoted twice, Agustín de Iturbide had himself proclaimed emperor of Mexico, paraded around in gold and silver braid for a year, then yielded to a potpourri of republicans, military opportunists, and the disenchanted of every stripe. No one knew how the emerging anti-clericalism or the hatred of Spaniards would affect the missions. With finance and politics in chaos, Pérez saw no reason to hurry payment. But Liberós, goaded by the pathetic sight of Tumacácori's unfinished church, refused to be put off. "I shall come to Chihuahua, Durango, Mexico City, or wherever I must if you continue deaf and oblivious to my supplications." By September, 1823, don Rafael Elías had guaranteed payment of the entire outstanding balance plus collection costs. The friar had won. [23]

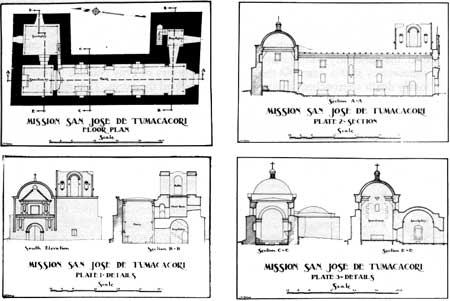

As far as Liberós was concerned, if the church at Tumacácori did not rival those of San Xavier or Caborca, by the grace of God it would serve. The insurrection, forced loans, and uncertainty about the future had rendered the original splendid plan of Narciso Gutiérrez an impossible dream. Whether by order of Gutiérrez himself, Estelric, or Liberós, the transept was closed up on both sides, leaving the nave a simple rectangle. Unfired adobes, easier and cheaper, heightened the walls course by course, with fired brick reserved for capping and other points of stress and for decoration. The hope of twin bell towers vanished: one on the right containing the baptistry at ground level would suffice. Instead of a barrel vault or a series of domes the nave walls at Tumacácori would carry a flat roof. [24] To Ramón Liberós the distasteful business of debt collecting was a lesser evil than a mission without a church. Confidently he went ahead with construction. On October 1, 1822, he blessed a large, walled cemetery immediately behind the new church. The same day in the place reserved for children he buried María Teresa González, five-year-old daughter of a Pima couple. He headed a fresh page of the burial book CEMENTERIO NUEBO and began numbering again from one. At the foot of that page Liberós noted a particularly solemn event. Despite the scaffolding and piles of brick still evident on all sides, Tumacácori's massive new church could at last be put to use. Evidently the dome over the sanctuary was finished, the nave roofed, and the planned bell tower unnecessary at this stage. As the second anniversary of Fray Narciso Gutiérrez lonely death approached, Father Liberós scheduled the event. That day, Friday the thirteenth of December, with all due ceremony he removed the remaining of Fathers Carrillo and Gutiérrez—who between them had served the mission forty years—from the old dilapidated church, and had them borne to the new one. Beneath the floor of the sanctuary on the Gospel side he reburied them. Though Narciso Gutiérrez had not entered his new church in joyful procession. at least his mortal remains now rested within the walls he had begun two decades before. And though they never would finish it, the Franciscans finally had a church. [25] As he baptized their newborn, married their lovers, and buried their dead, Ramón Liberós came to know them all, Indians, Spaniards, and half-breeds. The new friar, devout and energetic, seemed above scandal which was something of a relief. He earned their respect if not their attention to religious duty. He met and apparently did not quarrel with the recently promoted Captain Ignacio Elías González of Tubac. On the feast of Saint Francis, October 4, 1822, while Elías and his wife doña María Soledad Grijalva stood as godparents, Liberós insisted that visiting Fray Juan Vañó of San Xavier and Tucson baptize a three-year-old Apache girl, naming her Francisca Vañó. The new friar worked effectively through mission foreman José Antonio Orozco, who with his wife Gertrudis Sosa was among the community's more popular godparents. The number of gente de razón who looked to Father Ramón continued to increase as old families resettled and new ones moved in on neighboring lands. He officiated at more baptisms than last rites. From the ranchos of Buenavista, Santa Bárbara, and San Lázaro south of Guevavi, and from Arivaca to the west they came in or sent word to him. One wonders if don Francisco Perea of the Bernalillo, New Mexico, rico family was looking into old mines in the area when he died at the rancho of Arivaca late in August, 1822. Ramón Pamplona, the friar's tocayo, held the cane of office as the mission's native governor. Born at Tumacácori early in the morning on August 30, 1785, legitimate son of Miguel Antonio Pamplona, a Pápago, and Josépha Ocoboa, a Yaqui, the future governor had been baptized Raimundo next day by Fray Baltazar Carrillo. The infant's brothers and sisters died almost as fast as they were born. When he was seven his father, still only "about twenty-four," sickened and died. Eight months later his mother married Juan José Zúñiga, a Pápago widower about thirty.

On Fray Narciso Gutiérrez' 1801 census the sixteen-year-old Ramón Pamplona, listed as fourteen and a Pima, showed up with his stepfather and his mother, her only surviving child. On May 4, 1803, he married Gertrudis Medina, a Tumacácori Pima, thirteen. By her during the next eighteen years he had several children, at least two of whom died in infancy. Pamplona had been a member of the land grant delegation to Arizpe late in 1806. In June, 1821, Fray Juan Bautista Estelric buried his first wife and seven weeks later married him to his second, María Leocadia Castillo of Tucson. Liberós baptized the couple's first child, Ignacio, on August 1, 1822, and buried him eighteen days later. [26] Father Liberós learned to live with the uncertainties of the times. Still, he must have pondered the bishop's reason in 1822 for requesting an inventory of all the silver objects in the mission churches of Pimería Alta. Forced loan? Secularization? At the bidding of Father President González the friars complied, listing each item and its weight. The total came to 489 marks four ounces. Sáric was by far the poorest in silver, with just under twenty marks. Surprisingly, San Xavier del Bac, with its grand church and its visita of Tucson, ranked next poorest with thirty-five marks. Richest in silver was Tubutama which possessed a single magnificent altar lamp weighing forty-five marks. Tumácacori's church silver as itemized by Liberós added up to thirty-five marks three ounces and included monstrance, chalice with paten, censer and incensory, image (paz), small plate and altar bell, cross, six medium-sized candlesticks, medium-sized cross and the base of another, baptismal shell, small box with cruets and chrismatories. By the end of the year Bishop Espíritu Santo had the figures. [27] As stewards of their missions' temporal estates, Ramón Liberós and his fellow friars were expected to take the Indians' part in land litigation, to defend the integrity of mission grants against a growing number of non-Indian claimants. In September, 1820, the Arivaca heirs, don Tomás and don Ignacio Ortiz, had petitioned the intendant-governor for a new estancia grant twice as large north of Tubac. They wanted four sitios, of one league each, centering on the place called La Canoa. Nine months later the authorities in Arizpe admitted the petition and ordered Commander Elías of Tubac to proceed in the matter. Swearing in his survey team—Lieutenant Manuel de León, surveyor of the Tumacácori grant fourteen years before, José Antonio Figueroa, Juan José Orosco, and Manuel Castro—Elías had supervised the laying out of the grant in July 1821 and its appraisal at thirty pesos a sitio, or one hundred and twenty pesos for the entire claim. Back at Tubac he formally announced the initial auction as required by law. For thirty consecutive days, from July 14 through August 12, the drums were beaten in the Tubac plaza and Reyes Cruz cried the four sitios in favor of the Ortiz brothers at thirty pesos a sitio. Not until the final day did a rival bidder appear. It was Fray Juan Vañó of San Xavier. As surveyed, the Canoa grant for about ten miles bounded on the west the mission lands of San Xavier. Father Vañó, pressured by gente de razón in the Tucson area, hoped to acquire La Canoa as an additional estancia for the mission's thousands of head of stock. Representing Javier Ignacio Sánchez and Francisco Flores, who accompanied him, and all the other people of San Xavier del Bac, Fray Juan began bidding against the Ortiz brothers. Apparently they did not expect him to stay beyond fifty pesos a sitio. When he bid 52-1/2, they dropped out. After Elías had heard the testimony of three witnesses vouching for Fray Juan's ability to stock the grant, he forwarded the proceedings to Arizpe. The final three-day auction was set in the capital for December 13, 14, and 15, 1821. On the third day the agent of the Ortiz brothers reopened the bidding against the agent of Father Vanó. This time, when the bid reached 62-1/2 pesos per sitio, the Franciscan's agent dropped out. Four days later Tomás and Ignacio Ortiz owned the Canoa grant. Juan Vanó had tried. [28]

At Tumacácori the "phlegmatic" Father Estelric, who sold off most of the mission's cattle, had evidently paid little attention when don León Herreros of Tubac laid claim by denuncia to the abandoned lands of Sonoita, until 1773 a visita of Tumacácori. Comandante Elías in June, 1821, had surveyed one and three-quarters sitios along Sonoita Creek, appraised because of available water at sixty pesos a sitio. Herreros had closed the deal in November. The following year the mission Indians complained to their new friar, the tall, blue-eyed Liberós. Herreros' stock was invading their fields in the lower canyon of Sonoita Creek southeast of Tumacácori. Father Liberós prepared their case. He presented documentation to show that former Intendant-Governor García Conde had granted the mission community not only fundo and estancia as surveyed in 1807, but additional lands both to the east and to the south, the old Jesuit purchases. Confronted by Liberós, don León Herreros assured the forceful Franciscan that he had not meant to encroach. When measuring the claim the surveyors had descended the canyon from the ruins of Sonoita as far as the two small hills called Los Cuates, today Twin Buttes. Observing the boundaries of the mission's fundo and estancia, but unaware of the additional lands, they "believed that far from encroaching on the Tumacácori grant there existed between an unclaimed void of about a league more or less." Father Liberós and don León settled out of court. Appearing before Captain Elías and witnesses at Tubac on January 10, 1823, they agreed to draw the dividing line at the hill known as the Loma de las Cruces. Herreros retained the right to run stock downcanyon, guaranteeing in turn the Indians' exclusive right to farm the arable land in the lower canyon. Four years later the same parties would appear before Judge Trinidad Irigoyen to attest the transfer of "the rancho of Sonoita" to the mission. But because the deal was never recorded in Arizpe, and because Liberós and the other Spanish friars were expelled in 1828, don León would retain title and sell the grant again in 1831 to Joaquín Vicente Elías for two hundred fanegas of wheat. [29] By the spring of 1823 Father Ramón's motley flock, what with mission, presidio, and scattered ranchos, must have numbered some six or seven hundred souls. He could handle the hardest of them when it came to debts or land encroachments, but spiritually some of them tried him almost beyond endurance. Their inattention even to annual confession and communion made the friar want to cry out for deliverance from this Babylon. "I have not ceased," he professed to the bishop in despair, "insofar as it has been possible for me, to guide them along the path of salvation. Yet some, unmindful of the end for which God Our Lord created them, live as if they were not Christians and scorn the precepts of Our Holy Mother Church." From the pulpit and in private he had admonished them. "And the result has been scorn, babbling, and a reluctance to confess." There were those, he blurted out, who had not confessed for seven or eight years! [30] The bishop answered promptly. He had little patience with knowing transgressors. Father Liberós must formally admonish at Mass on three feast days all who had not fulfilled their annual obligations, giving them two months to comply. If that failed to move them, he was to excommunicate them and post their names on the doors of the church. "If even then they do not submit obediently to the mandates of Our Holy Mother Church you will intensify and reintensify the censure to the point of anathema." Although the Third Mexican Council had denied parish priests the faculty of absolving the contrite and repentant of anathema, the bishop conceded it to Liberós for the time being. [31] But then Bishop Espíritu Santo did not have to live with these people. Twice early in 1824 Liberós left Tumacácori, and twice an unfortunate soul died without the sacraments. During February, with a license from Father President González, he may have traveled to Arizpe on business. He had given don Rafael Elías until May 14 to pay the balance—6,366 pesos four reales—owing for the mission cattle. Then during Lent, Fray Ramón rode north to San Xavier del Bac to confess and do his annual spiritual exercises with his neighbor Juan Vanó. By mid-June a helper had come to Tumacácori, Liberós' first and last compañero. Only twenty-eight, Fray Juan Maldonado had the advantage of being Mexican. A native of Querétaro, born November 24, 1795, Maldonado had joined the order at the convento of Nuestra Señora del Pueblito in 1812 and four years later, at the height of the scandals, transferred to the college. He stayed at Tumacácori only about six months. [32] Every muleteer brought word of new crises. The liberator and ex-emperor Agustín de Iturbide, ill-served by his advisers, had returned from exile and died in front of a firing squad, but his legacy of military coup, opportunism, and disregard for law lived on in the hearts of his countrymen. A liberal congress had pasted together a federalist constitution which reversed overnight three hundred years of centralist rule. Sonora had no sooner been joined to more populous Sinaloa in the Estado Libre de Occidente when Sonorans began espousing separatism and self-destiny. Behind closed doors, in homes, shops, offices, wherever the upper and informed classes met, the same issues were argued: King or president? Centralism or localism? The one true faith or religious toleration? Abide the Spaniards or expel them? Confiscate the missions or let them be? Though the 1825 constitution of the Estado de Occidente declared Apostolic Roman Catholicism the only acceptable religion, it made no mention of the missions. They simply did not fit the liberal, egalitarian mold. As vestiges of Spanish colonialism, manned largely by Spaniards, no longer protected by Spanish law and tradition, they were more vulnerable now than ever. They survived only by the grace of inertia. Spain had chosen not to recognize the independence of her erstwhile colony. In retaliation Mexicans trampled Iturbide's pragmatic guarantee of equality for Spaniards, designed to enlist their support in consummating independence. It had served. Many peninsulares fled persecution in Mexico taking their skills and their wealth with them. The republic passed repressive laws against those who remained. As the tide of hispanophobia rose, the missions more covetous neighbors began to help themselves. When Juan Vanó moved down from San Xavier to San Ignacio to assume the job of Father President in 1824, he found himself practically engulfed. With no more than a few dozen mission Indians in the midst of 1,500 gente de razón, he was helpless to prevent encroachment. The settlers treated him with contempt, moving in to peddle their vices—aguardiente, gambling, whoring, and mockery of law and order. Early in 1825 the vice governor of the state, having heard about conditions in Pimería Alta, took it upon himself to lecture the constitutional alcaldes, and the missionaries, on the responsibilities of liberty. "It is not libertinism or a relaxation of custom. . . . I urge very especially the Reverend Father Missionaries to punish and correct public scandals and to insure that subordination and respect due their station." How, Father President Vanó wanted to know. [33] Some government officials kept on paying lip service to the missions, but certainly no money. As if to set accounts straight, someone in the treasury office in Arizpe went to the trouble of adding up what the Mexican republic, as heir to the Spanish crown, owed the missions of Pimería Alta as of January 1, 1825. It came to 33,642 pesos, two reales, six granos. The figure did not include the cost of provisions supplied to the presidios and the army by the missions, of which there was no record. Tumacácori had not received the 350-peso annual subsidy for eleven years, or its share of the 8,000 pesos deposited for the college in the treasury back in 1813. A forced purchase of lottery tickets in the spring of 1817 added another 120 pesos. When a three-percent tax levied in support of the Mexican Church Council was deducted, the treasury admitted a debt to Tumacácori on paper of over 4,400 pesos. But Father Liberós never saw one peso of it. [34] The college suffered too. Fray Ángel Alonso de Prado, the last Queretaran recruiter sent by the superiors to Spain, had secured on December 20, 1819, royal approval to collect a mission of thirty priests and two lay brothers. But before he had half a dozen signed up, the Spanish liberal revolt of 1820 threw the country into chaos. The next year Mexico cast off from troubled Spain. When Prado returned to Querétaro late in 1822 he brought with him only four recruits "who served little or not at all in the ministry." In 1823 the community elected Prado Father Guardian for the third time. He died in office. The next regularly elected guardian, ex-Father Prefect Francisco Núñez, was forced to retire after only three months by a Mexican decree against Spaniards holding office. That precipitated a crisis from which the mother college never fully recovered. Because Núñez had been elected canonically and deposed by civil authority of the Mexican government, the friars, at least the Spanish majority, refused to recognize his dismissal. That irked the criollo minority. When the Spaniards chose old Fray Diego Bringas, the college's most illustrious American-born son, as Father President—not guardian—the criollos boiled. In sentiment Bringas was more Spanish than the king. The criollos felt cheated—and on their own soil. They counted up the number of Mexican-born candidates who had been refused admission, and charged discrimination. Outside the walls the people had begun shouting slogans against all Spaniards. Inside, when three criollo friars roughed up Father Bringas in his own cell, the Spanish friars, and Bringas, began thinking of home. The community had broken asunder. [35] The friars in the missions knew what was going on. Even before the Mexicans deposed Guardian Núñez, Ramón Liberós had threatened to quit. Writing late in 1825 to an unnamed fellow missionary, probably Miguel Montes of Oquitoa, he confided his discontent.

Father Ramón had another complaint. The Apaches, after a generation of relative calm, seemed to have again taken the offensive. Not that all of them had ever observed the peace or accepted welfare, but enough had to lower the intensity of the war from its peak in the 1770s and 1780s. Enlisting the "tame Apaches" as auxiliaries and scouts, the presidial garrisons, who never ceased campaigning, had held the hostiles pretty much at bay. But in the welter of insurrection and independence, the dole reached the Apache peace camps less regularly and sometimes not at all. Some warriors shook off the effects of wardship and returned to the mountains. Others tried to play it both ways, to be Apaches de paz one week and Apaches de guerra the next. As ranchers like Ignacio Pérez moved their herds out onto sprawling new grants and closer to hostile territory, depredations mounted. When Apaches ran off a bunch of Tumacácori horses on All Saints' Day, November 1, 1824, Father Ramón had no illusions of swift retaliation. As chaplain at Tubac he knew all too well the sorry state of the garrison. The Pimas of the pueblo had taken off in pursuit without waiting for acting post commander Teodoro Aros to marshal the presidio. When he did, the force amounted to three soldiers and four civilians. The local alcalde said there were no horses on which to mount the citizens. "I could not force them to go afoot," fumed Aros. It made him mad, the whole thing. Only Lieutenant José Rosario, besides he himself, was fit to lead. And they had no one to lead. What did his superiors expect? With his dander up, Aros wrote Commandant General Mariano de Urrea. The presidial horse herd would be next. Who was supposed to command the guard detail? "I have it for life since the carabineer cannot be trusted . . . because he is so negligent and so dense that even when the most exact orders are given to him and precautions taken to assure the fulfillment of his duties, it amounts to nothing." Again the Tubac garrison was scattered all over the place. Sergeant Antonio Ramírez had helped quell an Ópata uprising in September. Ensign Rafael Arriola and eighteen infantrymen were in Arizpe about to join a campaign against the Coyotero Apaches. "Unless Your Lordship releases the officers of this company who are in the capital, I think that in no time we will have no horse herd at all." In conclusion Aros told what had almost happened—but for divine providence—when the dunderheaded carabineer was guarding the horses.

A couple of months later Chief Antuna and twenty-seven of his Apaches de paz of Tucson relieved some enemy Apaches of seventeen animals stolen from don León Herreros' Sonoita ranch. But when a hungry band allegedly from the same camp came upon a vaquero from Arivaca with a couple of cattle tied together horn to horn, they appropriated the animals, slaughtered them on the spot, and carried the meat to their rancherías. [38] Naturally Liberós was concerned. "You may know by now," he told his friend, "that on Thursday night [November 17, 1825] the Apaches attacked Santa Bárbara," south of Guevavi. Because there happened to be plenty of people around at the time, the marauders did no more damage than wound a vaquero, kill a horse, and steal a couple of trunks of clothing belonging to some travelers. The same night about twenty approached Tumacácori and stole a little thrashed wheat left in the fields by the Pimas. But on Saturday the commandant at Tubac had warned Liberós that two large war parties were in the area. One was headed their way. "Who knows what will happen?" [39] For all the old reasons—territorial expansion, supply and trade, defense against hostile Indians and foreign interlopers, even conversion of the heathen—the rulers of independent Mexico fancied a highway between Sonora and California. Diplomacy with the tribes of the Gila and Colorado Rivers again took on all the urgency of Garcés' and Anza's day. In the spring of 1823 a Dominican missionary of Baja California, Father Félix Caballero, had crossed the lower Colorado in Cócopa territory and reported to Antonio Narbona in Arizpe. A squad of eleven men under Brevet Captain José Romero left Tucson in the searing heat of June to escort the friar back and to reopen the way to Monterey. Skirting the formidable Yumas and relying on their enemies, the party had crossed downriver and made it to California, where Romero found himself detained for two and a half years. Back at Tucson a rumor had it that all hands had been killed by the Yumas. [40]

The Gila Pimas had watched Romero pass. A visit from Father Prefect Francisco Núñez in 1823 had stirred in them the old hopes of whatever benefits baptism might bring. "Battered by the enemy Apaches," they were clamoring again. From Tucson Pedro Ríos, who had served as interpreter not only for Núñez but also for Father Bringas in 1795, informed Commandant General Urrea that these Gileños wanted to know why, after so many promises, no missionaries had come to live with them and to baptize their children. Ríos himself claimed to have baptized many in danger of death. He appealed to Urrea to pass on the Gileños' pleas to the proper authorities, and in the meantime to send them the dozen hoes they had asked for. [41] Urrea agreed. He saw the Gileños as the key to northwestward expansion. They were friends of the Cocomaricopas and Halchidhomas and enemies of Apaches to the east and Yumas to the west. If the Mexicans could arrange a peace with the Yumas and unite all the tribes of the Gila and Colorado against the Apaches, colonization and the road to California would be assured. Straightaway he summoned native leaders to Arizpe to make the necessary treaties. Twenty-seven Gileños showed, but not one Yuma. The commandant had nothing but praise for the Gila Pimas. They had consistently sought conversion. They lived in fixed rancherías. They irrigated their wheat, maize, beans, and cotton "by means of their check dam of staked logs that the flood of the river carries down to them each year." He stressed their trade with Tucson, Tubac, and the rest of the frontier. A ready market existed for their cotton cloth, skillfully woven on horizontal stake looms, for their beautiful cat-claw baskets, and for the deerskins they prepared. With modern tools and technical training, Urrea believed, their production and trade could be greatly increased. But most of all they must be brought to a knowledge of God. Receiving the visiting Gileño principales graciously, Urrea confirmed them in office as justicias and gave them provisions. They asked for canes of office, and he promised to send them along later. He did not have the money to buy them, he told the vice governor. For the benefit of the government the commandant listed the Gila Pimas according to rancherías, padding the total with some Pápagos and Cocomaricopas: [42]

Politics, the tumultuous internal power struggle that gripped Sonora for most of the nineteenth century, now burst the expansionists' bubble. Mariano de Urrea, who had twice in 1824 defied orders from Mexico City to surrender his dual military and political chieftanship in Sonora and Sinaloa, yielded civil authority to the new Estado de Occidente but refused to step down as the state's commandant general. In true caudillo style he ordered his officers to pronounce against the national government and to resist General José de Figueroa, dispatched to remove him. But Figueroa proved more than a match for Urrea. By the summer of 1825 don Mariano was on the road to Mexico City under guard, charged with defiance of the federal government, inciting the Indians, and attempting to set himself up as an independent "King of Sonora." [43]

Figueroa tried to pick up the Gila Pimas, the Yumas, and the road to California where Urrea had dropped them. Writing to the authorities in Mexico City, the general assured them in August that they could "count on the friendship of the Gileños, Cocomaricopas, and Yumas because for many years they have lived in peace without committing hostilities on our frontiers. They are of a peaceful character and most inclined to live in society." A liberal, Figueroa saw the salvation of these "wretched beings" not in baptism but in education. He would, however, do all he could to support new missions when missionaries were assigned. The outlander identified certain requisites to regular intercourse between Sonora and Alta California: (1) a chain of military posts along a two-hundred-league stretch of desert frontier; (2) the acquisition of a thorough preliminary knowledge of terrain and Indians on the route, recognizing that many, especially the fearsome, numerous, and unregenerate Apaches, were hostile; and (3) protection for new missions. At the same time he criticized his predecessor for not waging active war against the Apaches; vowed to fight the traffic in Indian captives; and proposed "a formal and respectable expedition" to escort José Romero back from Alta California, reconnoiter the route, and make peace between the tribes. [44] To the south at Fuerte, temporary capital of the Estado de Occidente, Governor Simón Elías González was proposing for the Gila Pimas "a new system of missions in this part of the United Mexican States where the one adopted by the Spanish government caused the tragedy of the Río Colorado and still feeds the backwardness of Pimería Alta." His eleven-point reform, a curious mixture of experience and naiveté, presupposed conditions that did not exist. The government was not solvent, nor the friars eager. The Gileños were not conveniently isolated or free of the Yumas' "greed." Besides, no two politicos could agree on any eleven points. First, taking a page from Francisco Garcés, Elías urged a gradual approach to the Gileños. Two Queretaran priests and two lay brothers should be assigned to mission San Xavier del Bac. There in the company of the resident friar they would learn the language, work with Gileño children, and at opportune times of the year visit the rest of the tribe. They must go alone, unaccompanied by soldiers or settlers or interpreters, in the true manner of apostles. Then, among those who accepted them, they would build a small but sturdy settlement, the embodiment of religion and civil society, and move in. Communal property and communal labor were strictly forbidden—they must instead find better means of generating funds and a new name for the work required to build the chapel, school, and other structures. The government, according to the Elías plan, was to provide all necessary aid—tools, gifts, and the annual stipend, which the missionaries in Pimería Alta had not seen in years—as well as close supervision. The state would assist in appointing qualified friars, provide them with regulations and forms for periodic reports, and determine when and what the "mission" was to become after the missionaries' job was done. During their tenure the friars must encourage arts and trades, "carpentry, iron working, weaving, ceramics, and the rest." Under no circumstances were the friars to get mixed up in the wars of their charges. [45] In mid-November 1825, General Figueroa met the Yumas on their own ground. He had marched out from Tucson at the head of a respectable expedition of four hundred men. Now the Mexican force faced "4,000" menacing Yumas across the Río Colorado. Figueroa sent emissaries. The principal, Carga Muchachas (He Molests Girls), and a large following crossed over to parley. In exchange for gifts he gladly made peace and agreed to deliver dispatches to Romero who was finally on the way from California. Just then bad news reached the general. The Yaquis had rebelled. Again the internal convulsions of Sonora wrecked the expansionists' plans. Instead of awaiting Romero on the Colorado, Figueroa marched back double time the way he had come. [46] Ramón Liberós took the events of 1825 in stride. He was not one to panic. After he had described for his unnamed friend the Apache menace the rest of his letter was almost breezy. He went on about stolen and strayed horses and mentioned a trip he planned to take, "God willing, this coming year after Epiphany." He knew about the Yaqui revolt and Figueroa's retreat from the Río Colorado. "Now that they say the troops are coming from the Colorado, my Pimas have not a care in the world. They are dancing vigorously and practicing for the matachines. Already they do it well, especially your compadre Cayetano." Father Ramón invited his friend to come to Tumacácori and preach, and he offered to send an escort. After a final slap at Father Faustino González, Liberós initialed the personal note and gave it to an Indian to deliver. [47] Liberós already had one house guest. Fray Rafael Díaz, Juan Vañó's replacement at San Xavier and Tucson in 1824, had been carried to Tumacácori desperately ill. While he lay abed three women of the Tucson presidio died without the sacraments. Fearing that he might be charged unjustly with neglecting his duties, Díaz asked three of the community's leading citizens to testify in his behalf. The week of November 20, 1825, acting commandant Brevet Captain Manuel de León, surveyor of the Tumacácori grant in 1807, don Teodoro Ramírez, and Alcalde Constitucional José León all signed identical statements for the bishop praising Rafael Díaz as a pastor. Willingly he risked his life, coming out from San Xavier "at all hours of the night" to hear a confession. Once when he was totally paralyzed he had insisted that they carry him in a sedan chair to the side of a sick woman. As for the three who had died while Díaz lay indisposed at Tumacácori, death had claimed one suddenly and the other two had been remiss in not summoning Liberós. In other words, their dying without the sacraments was not Díaz' fault. [48] In 1826 another of the periodic "universal" epidemics swept Pimería Alta, ten years after the last one. Identified as measles, it ravaged the missions, killing off "a large part" of the neophytes. At Tumacácori Ramón Liberós emerged with only eighteen families plus a few children whom he cared for in the convento. [49] Later that year Father Ramón heard a rumor that was soon confirmed. Americanos had descended the Gila as far as the Gileño and Cocomaricopa rancherías. A Gila Pima governor had told Captain León of Tucson. León had dispatched Brevet Lieutenant Antonio Comadurán with a small party, including Tucson Alcalde Ignacio Pacheco. On the Gila Pacheco called a council of the principales. The Indians said that the sixteen armed foreigners, three of whom spoke Spanish, had come only to investigate the possibilities of beaver hunting and trade. They had done no harm. They had given the Indians gifts. They had departed after four days. They had claimed to have the permission of Antonio Narbona, now governor of New Mexico. That fact the Mexicans were able to verify, thanks to the Cocomaricopas' theft of a valise belonging to the American "captain." It contained a passport issued by Narbona in Santa Fe, August 29, 1826, to S. W. "Old Bill" Williams, Ceran St. Vrain, and thirty-five others. [50] The following December a couple of Indians came down from the Gila to Tucson to report two more companies of American trappers. Because of threats from the Cocomaricopas, the Americans had gone back the way they had come in. But now there was bad blood between the Cocomaricopas, who wanted to kill the foreigners, and the Pápagos who refused to let them. The two Indian emissaries asked the Mexican authorities at Tucson to forbid any more Americans to enter. In response Captain León gave them a paper ordering any and all foreigners to proceed no farther but to present themselves in Tucson. Almost immediately the order brought results. On the last day of 1826 three unidentified americanos showed up at Tucson, the first recorded visit of United States citizens to Hispanic Arizona. They had been shown the captain's order by some Pápagos. They had come to present their passports. Although León likely explained to them that they were unwelcome in the Estado de Occidente, he evidently did not prevent them from returning to New Mexico. [51] It was difficult to see manifest destiny in this trio. Still, Anglo-American penetration had begun. From 1826 on, a drifting array of trappers and traders, bounty hunters and filibusters wandered in and out of the Santa Cruz Valley. Thirty years later the United States Army would raise the stars and stripes over Tucson. Of more immediate concern to Mexican residents of the valley in 1827 was the Yaqui scare. A dispatch from the commandant of Tubac in "La Canatua" and warnings from the Apache leaders Antuna and José de Santa Cruz had the people of Tucson worried. Yaqui rebels were reported ready to attack the post. If they should win over as allies Pápagos, Yumas, and the Coyotero Apaches "who attack us most months," there would be no stopping them. Most of the garrison had gone south to fight Yaquis. Hastily, "in harmony and in patriotism," the citizens of Tucson rallied to repair the presidial wall. The attack never came. The Yaquis surrendered to General Figueroa three hundred and fifty miles away. [52] With what he could scrape together Father Liberós kept working on the Tumacácori church. But to him and to the other Spanish friars it now seemed only a matter of time. Their college, rent from within, offered them no support. The politicos of the Estado de Occidente, intent on their own intrigues, could not agree on what to do with the missions, to tolerate them as buffers against hostile Apaches or to suppress them and enjoy the fruits of their Indians. Spain still refused to recognize independent Mexico. It was rumored in fact that Ferdinand VII, restored again to his absolutist throne by foreign intervention, had resolved to reconquer New Spain. When the currents of sentiment against Spaniards and against the missions flowed together, the Queretaran friars of Pimería Alta were sure to drown in the flood. Five days before Christmas of 1827 the federal congress passed the expected law expelling Spaniards from Mexico. The states followed suit. Though most of the Spanish friars residing at the college in Querétaro would have qualified as exceptions because of age, poor health, or useful vocation, they had decided "with profound regret" to leave. Most in fact had anticipated the decree and made for Vera Cruz several months before. Fray Diego Bringas, known as an irreconcilable royalist from California to Tehuantepec, went with them. Hardly had the overcrowded British frigate cleared port with its motley cargo of rich merchants and poor clerks, shopkeepers, artisans, soldiers, and friars, than Father Bringas had gathered around him a circle of eager persons who believed that Spain could reconquer Mexico. They considered Bringas a saint, in the words of one, "the Saint Francis Xavier of this century." In New Orleans and later in Havana Fray Diego preached and plotted for the cause, the return of wayward Mexico to her rightful sovereign. When Isidro Barradas' quixotic invasion force put out from Havana in 1829, the fervent Diego Bringas accompanied it as chaplain. Its pathetic defeat on the coast of Tampico all but dashed the royalists' dream. [53] Meanwhile, in conformity with the national act, the Estado de Occidente enacted its version of the law expelling Spaniards, but rumor traveled faster. Excited crowds gathered in the towns of northern Sonora and demanded action of one sort or another from officials who had not received copies of national or state law. In Arizpe the city fathers convened in January, 1828, to draft a patriotic and uncompromising decree of expulsion for consideration by the state legislature. As late as March officials of the department of Arizpe, comprising the districts of Arizpe, Oposura, and Altar, had made no move to expel the Spanish friars of Pimería Alta. Who would administer the sacraments when they left? At this juncture the state's military chief, Comandante de Armas Mariano Paredes Arrillaga, intervened. [54] Paredes, it seemed, had "reliable reports," one from the commander at Tubac, that the missionaries were preaching sedition to the Indians, urging them to resist if anyone should try to expel their Padres. The natives of Tumacácori and San Xavier were said to be on the verge of revolt. This was a matter for the military. He acted accordingly, issuing orders to the commandant of Tucson, Captain Pedro Villaescusa, son or nephew of the officer who had raised the San Rafael Company of Pimas forty-five years before. Villaescusa may have considered his commission unjust or prejudicial, as the friars claimed, but he complied. Orders were orders. [55] Sixty-one years earlier Captain Juan Bautista de Anza reportedly wept when he announced the Jesuit expulsion to Father Visitor Carlos de Roxas, the old priest who had baptized and married him. Now, according to a Franciscan account, in 1828 during holy week Captain Pedro Villaescusa stood outside the convento of San Ignacio, ashamed to go in, the bearer of similar sad tidings for his friend Fray Juan Vanó, the Father President. Vanó appeared. He looked relieved. Finally it was out in the open. He consoled the captain. As a soldier he must do his duty. All things considered, it was probably for the best. The second week in April Captain Villaescusa came to Tumacácori to expel Fray Ramón Liberós. Paredes' summary decree gave the Spanish gray-robe only three days to arrange his affairs and hit the road south. What about the mission's property, the livestock, stores, and tools, Liberós protested. Frankly, Villaescusa could not say: the comandante de armas had ordered the removal of the missionaries, no more no less. As a tentative measure Father Liberós named long-time native governor Ramón Pamplona mission administrator and charged him to pay off the debts still owing for work on the church. The friar wanted to leave the mission's rightful owners in charge, not gente de razón. Captain Villaescusa was supposed to explain to the Indians the reason for the government's action and impress upon them the punishment for resistance. They must remain calm. [56] After six trying years at Tumacácori it was all over for Ramón Liberós. He had been a good steward. Physically the mission had never looked better. The bell tower, still embraced by wooden scaffolding, lacked only a few courses of brick and the dome to be finished. The circular mortuary chapel in the new cemetery also needed a dome. Given a few more months, he might have completed the job. All in all the long-labored Franciscan church, despite a certain heaviness of proportion, was impressive, outside with its facade of tiered double columns and painted statue niches, its red roof-to-ground rainwater ducts and the dappled pattern in the stucco, the high clerestory windows, and the dome with steps up to the lantern. Inside, where earth reds, oranges, and pinks predominated, the nave appeared somewhat cluttered with four side altars protruding from the walls. Yet when one stood at the back of the church under the choir loft looking toward the raised sanctuary and main altar, the expanse from floor to roof vigas seemed very great. The wall designs, floral, geometric, scrollwork, wrought with straightedge, compass, and stencils, were plainly European not Indian. East of the church the large enclosed convento, with granary, kitchen, living quarters, shops, and storerooms, even in ruin, would give later travelers the impression that the friars of Tumacácori never lacked for anything. Before he rode out of Tumacácori for the last time, he took a fresh sheet of paper—later bound upside-down at the front of the surviving baptismal, marriage, and burial records—and hurriedly composed this note:

He did not look back. By the time Liberós reached San Ignacio, Father President Vanó had already left. The locals, who had made Vañó's life so miserable, now crowded around Father Liberós. They had a favor to ask. They wanted him to officiate at several weddings. No telling how long they would be without a priest. Recognizing their plight, the friar dispensed with the banns and on April 17 and 18 married in the eyes of the Church a half dozen couples. He united two more couples at Santa Ana, twenty miles farther south. A week later when Fray Rafael Díaz of San Xavier passed through, there were more waiting. [57] Meanwhile to the west an attempt to halt the expulsion aborted. On Easter Sunday, April 6, Comandante de Armas Paredes had written to don Juan José Tovar, temporarily in command at the presidio of Altar, informing him what Captain Villaescusa was doing and urging him to keep the public peace. On the eighth Tovar passed the word to the Altar town council. Next day a troubled Father Faustino González wrote from Caborca. He had received an order directly from Paredes telling him to vacate his mission immediately and without excuses. He could scarcely believe it. He had not preached revolution to his Indians. "The fact is that during the Yaqui revolt and every crisis I have endeavored to sustain peace and the present system."

The Altar council considered the matter. Why was the military chief judging the missionaries and invoking a law of expulsion which had not yet been promulgated in Pimería Alta by the civil authorities? He had plainly violated the federal constitution's guarantees against trial by mandate and retroactive laws. But what could they do? Displaying far more gumption than one would expect from a local politico, Alcalde Santiago Redondo openly challenged the comandante de armas. Directing an urgent appeal to the governor of the Estado de Occidente—at the moment don José María Gaxiola, political ally of Paredes—Citizen Redondo impugned the comandante's authority to expel the missionaries. That same day, April 9, the crusading alcalde tried to stop Captain Villaescusa. Since what his chief had ordered was plainly the prerogative of the state's governor, Redondo admonished Villaescusa to suspend the unconstitutional expulsion till the governor had spoken, or suffer whatever consequences might result. He assured the captain that calm prevailed in all the pueblos of his district: even if the Indians of Tumacácori and San Xavier did try to incite a rebellion, they would find no followers in the west. If on the other hand, once the law of expulsion was legally promulgated, any Indian dared take up arms in resistance, that beyond a doubt would be a matter for the military. [58] Captain Villaescusa, who did not answer Redondo's blast until April 22, refused flatly. Obviously his chief feared for the public safety: he had acted to preserve the peace, entirely within his authority, even to invoking the already decreed law of expulsion against the Spanish friars. "I must obey the orders of my chief, in spite of whatever charges you care to lodge against me. Such charges may well redound upon you should you continue obstructing the public safety and compliance with said law. This will serve for your guidance and as an answer to your communique." [59] The governor's reply was even tougher. Indeed the comandante de armas did have the authority to maintain the peace and enforce laws both federal and local. The reports against the missionaries of Pimería Alta were precise and documented. Furthermore, alleged the governor, the friars, fearing that the expulsion law would be executed, had been busy alienating and destroying mission property, and the town council of Altar had lifted not a finger to prevent it. Gaxiola reproached the councilmen severely for their unpatriotic attitude and sent them a new supply of the law for posting. [60] While the ayuntamiento of Altar abased itself before Governor Gaxiola, the expelled missionaries gathered at the makeshift hospice in Ures, all but Fray Faustino González. Even though Captain Villaescusa gave the fifty-six-year-old friar his three days to prepare for the journey, González had set out "with no more baggage than a blanket tied to his saddle and with nothing for sustenance but the breviary in his saddlebags." When he reached the mining camp of Cieneguilla the people would not let him proceed. They insisted that they would intercede with the authorities in his behalf. So he stayed, living on the alms he got for Masses and encouraged by don Francisco Javier Vázquez, the parish priest who had informed on Estelric four years earlier. Even though González' respiratory ailment should have exempted him to begin with, nearly two years passed before the authorities allowed him to return to Caborca. [61] The others found themselves detained at Ures during May 1828 subsisting on charity. Father García wrote to discourage the children of Cocóspera who wanted to visit him: he simply had nothing to give them. Most of the friars had resigned themselves to leaving, but not without a hearing. The charges of sedition against them they imputed to one of their avaricious neighbors in the Pimería, "a person ungodly since his earliest years." They knew that their opponents had trumped up the charges to discredit them, and that they had welcomed the law of expulsion as a means of removing them. Since the beginning there had been persons who coveted mission lands and Indian labor. It now seemed that they had won. Still, the charge of fomenting revolution galled them. One of their number, they decided, must travel to Álamos and appear before the governor to vindicate them, to request passports for the Puerto de Refugio, and to pick up the sum stipulated by the law of expulsion for religious and other Spaniards who could not afford the cost of travel. The job required confidence, persuasiveness, and above all an ability to deal with the politicos. They chose Ramón Liberós. [62] He failed to get the money. But he did apparently make a favorable impression on Governor Gaxiola. Because of the shortage of priests in the department of Álamos the friars were welcome to stay on there. Father President Vanó answered for the majority. "Seeing himself free now (without having requested it) of the responsibility that had weighed upon him so heavily, he spoke of nothing but leaving." Only two stayed, young Mexican-born Fray José María Pérez Llera and the Spaniard Fray Rafael Díaz who had friends in Arizpe. Pérez Llera intended to leave with his brothers. He was scared. If the government had banished Spaniards he feared that it might soon move against religious born in Mexico. The college of Querétaro would likely cease to exist as a separate entity, either stranding him or forcing him to join the Jalisco province. So he had asked for his passport. But when he began to feel "somewhat worse than usual," he had second thoughts and changed his mind. As Vanó and the others set out from Ures, the Father President commissioned Pérez Llera to make a visitation of the missions, to comfort those poor souls, baptize the newborn, and confess the sick. [63] Left alone, he was more scared than ever. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||