Contents Foreword Preface Jesuit Foundations Gray Robes for Black 1767-68 The Archreformer Backs Down 1768-72 Tumacácori or Troy? 1772-74 The Course of Empire 1774-76 The Promise and Default of the Provincias Internas 1776-81 The Challenge of a Reforming Bishop 1781-95 A Quarrel Among Friars 1795-1808 "Corruption Has Come Among Us" 1808-20 A Trampled Guarantee 1820-28 Hanging On 1828-56 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

FROM 1808 until the end of Spanish rule in Mexico world events intruded in Pimería Alta more frequently and with greater impact than ever before. The frontier missionaries, far from ignorant of the upheaval set in motion by the French Revolution, kept up with the news, much as it pained them. Back in 1795 Fray Francisco Iturralde had reacted emotionally at Tubutama to word that French armies had invaded Spanish soil: "I believe that the greatest sorrow I have felt in my life was upon receiving news of the misfortunes heaped upon my country by the French!" [1] Reaping the consequences of years of intrigue, compromise, and incompetence, Spain's ruling classes found themselves by 1808 unwilling hosts to a hundred thousand French troops, bereft of their monarchs Charles IV and Ferdinand VII, and faced with the imposition of Napoleon's brother Joseph as king. In New Spain the shocking chain of events aroused conflicting sentiments. To many of the criollos, the American-born Spaniards profoundly resentful of their peninsular "betters," here finally was the chance to cast out Spanish governors, Spanish army officers, and Spanish bishops. Since the Bourbon monarchy had toppled, they owed no allegiance to Spain, now a mere province of France. They favored, with varying intensity and commitment, an independent Mexico. Opposing them stood the powerful peninsulares who still ruled in government, army, and church. As Spanish patriots and royalists, to whom authority from anywhere but Spain was unthinkable, they looked to the resistance government and to restoration of the rightful king Ferdinand. With Commandant General Salcedo, they swore to give up their lives rather than submit to French domination. In May, 1809, the same month the friars of Pimería Alta dedicated the glorious new church at Caborca, another "solemn and joyous" ceremony took place in the capital of Arizpe. At 8:00 A.M. on the 28th an official party gathered in the main salon of the intendant-governor's residence to witness don Alejo García Conde swear allegiance to the Suprema Junta Central—the resistance government in Spain—and to Ferdinand VII, their king in exile. Afterward in his oration don Alejo urged on everyone a singular austerity for the duration. All must sacrifice. All must demonstrate their patriotism by contributing to the monies being collected for the war effort. Bells pealed, a triple volley of musketry was fired, and all joined in vivas to junta and king. A solemn Mass with Te Deum consummated the event. Five hundred and fifty miles farther south in Culiacán, where he had finally fixed the see of his diocese, Fray Francisco Rouset de Jesús, fourth bishop of Sonora, insisted on calm while echoing the intendant-governor's plea for contributions to drive the godless French invader from Spanish soil. The friars too would be expected to contribute. How under these circumstances was Narciso Gutiérrez ever to finish his church? [2] The Suprema Junta Central, fleeing before the French to Isla de León on the bay of Cádiz, yielded to a five-man regency which in desperation summoned the long-defunct Spanish parliament, the Cortes. With all due pomp and demonstration in Arizpe, García Conde acknowledged the regency and arranged for the election of a delegate from Sonora. That honor fell in the summer of 1810 to Licenciado don Manuel María Moreno, who as Bishop Rouset's deputy thirteen years before had come to Tumacácori on an official visitation later declared illegal. [3] But on September 16, 1810—a day that lives on in Mexico—before don Manuel María could book passage for Spain, all hell broke loose. From the time Napoleon upset the Spanish monarchy, criollo and peninsular had been jockeying for power. The intrigue in Mexico City, where two viceroys rose and fell by coup in rapid succession, was reflected in the provinces. A whole network of criollo cabals worked for independence. On the night of September 13 local authorities in Querétaro sought to break the back of one such group. Warned at the last minute, the leaders eluded capture and came together at the town of Dolores, sixty miles northwest. There in the early morning hours of September 16 the visionary parish priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla raised the grito de Dolores. Inflamed by his rhetoric, the Indians and mestizos of his parish chanted the new slogans: Viva la Independencia! Viva la Virgen de Guadalupe! But what they really took to heart was Death to the Spaniards! From the first confused and conflicting reports that reached them in their frontier missions, the friars of Pimería Alta feared that their college would be overrun by the rabble, their brethren butchered, and the building ransacked. All that happened and worse, but not in Querétaro. The insurgent band, grown into a great multitude of frenzied rural and urban downtrodden, armed with anything that would kill, had flowed west out of control. Taking Guanajuato, they slaughtered like hogs in a pen the hundreds of peninsulares, men, women, and children, who cowered with their possessions inside the public granary. For months rebel hordes hacked bloody paths across Mexico as their leaders vainly sought to harness their pent-up urge to kill. With the capital seemingly within his grasp a disillusioned Hidalgo steered his following west to Guadalajara. The ill-organized government put General Félix Calleja into the field. When he gained the upper hand, his carnage in retaliation matched the insurgents'. A year after the first grito Fray Ángel Alonso de Prado, guardian of the Querétaro college, detailed for the Franciscan commissary general in Spain the friars' glorious actions in support of God and king. The original plot uncovered in Querétaro, said Prado, had called for slitting the throats of all the friars without exception. Sensing the subsequent unrest in the city, the guardian had sent the entire household, save lay brothers and the ill, into the streets and plazas to preach the Gospel against the rebellion, against Freemasonry, against Napoleon and atheism, doctrines "so clearly false and even ridiculous that they could seduce only fools, which Hidalgo and his followers were." Rebel sympathizers, "sowing darnel among the pure grain of God's word," had spread rumors among the people that the friars were opposed to the insurrection only because they were Spaniards, only because they were being paid handsomely for their efforts. The grayrobes were said to be "heretics, Jews, etc." It seemed incredible to Prado how the people's warm appreciation of the college for a hundred and thirty years could change in an instant to voracious hatred. Reluctantly, he had taken the friars off the streets for their own safety. Thank God he could proclaim that no member of the college had gone over to the insurgent party. Queretaran friars served mainly with royalist forces. They had helped set up and maintain a troop hospital in Querétaro. They had inspired the city's defenders during the rebels' October 30 assault, when mortars lobbed a hundred stones into the college, into the friars' very cells. As chaplains they had shared the glory and the hell of battle. New Spain, Prado assured his superior, recognized the college's singular contribution to the royalist cause, not only in preventing strategic Querétaro from falling to the insurgents but also on the field of battle. For all this the friars had charged nothing. One Queretaran emerged from the insurrection with a national reputation. He was Diego Miguel Bringas, born in Mexico but intensely loyal to Spain and the king. He had been working at the college's Pames Indian mission of Arnedo, some seventy miles north of Querétaro, when General Calleja marched through. The zealous, articulate Bringas joined the Regiment of San Carlos as chaplain. For more than a year he served with Calleja, sharing all the general's victories, "preaching, exhorting, and freeing the faithful of so many errors with indefatigable zeal." He also published patriotic tracts. [4] As a reward for Bringas' "incalculable" services, General Calleja, who became viceroy in 1813, secured for the Queretaran the titles of honorary chaplain and preacher of the king. His fiery royalist sermons made Father Bringas the viceroyalty's best-known preacher. When Intendant-Governor García Conde of Sonora suggested splitting the enormous diocese of Sonora in two he could think of no better candidate for the new see than Diego Miguel Bringas. He would make, García Conde believed, "a wise and virtuous prelate of surpassing patriotism." [5] Not all the friars proclaimed the royalist doctrine with Bringas' ardor. Still, the missionaries in Pimería Alta rejoiced at the news that García Conde had routed the rebel force of José María González de Hermosillo at Piaxtla in February, 1811. The service records of all who saw action that day, including hundreds of presidials ordered south to meet the rebel invasion, henceforth contained a proud description of their deeds. From the service record of Tubac's pockmarked veteran Sergeant Ambrosio Sambrano:

What worried the friars was that Sergeant Sambrano and many other frontier troops remained on duty in the interior for years, presumably to keep the province safe from insurgents. Later in 1811 they had learned that Hidalgo had been captured and shot. Everywhere, reported the government press, royalist forces had taken the offensive and were mopping up the rabble. Mean while the Provincias Internas suffered. The military dislocation of frontier troops left the presidios undermanned. The interruption of commerce and agriculture in central New Spain had resulted in widespread shortages. And who knew when or where the race war and carnage would erupt again? [7] While the early, ghastly stages of the war for Mexican independence ran their course—terrifying everyone of property, criollo and peninsular alike—and Englishmen joined Spaniards to battle the French in Spain, liberals from both sides of the Atlantic sitting in the Cortes at Cádiz had reshaped the empire in parliamentary debate. Not content merely to lend unified support to the war effort against Napoleon, as their absolutist king in exile wished, they proclaimed a limited constitutional monarchy, an elected parliament, and equality of criollo and peninsular. As the beleaguered empire fought for its life, the Cortes in Cádiz gave to the world the Spanish constitution of 1812. Displaying their well-known tenacity, as well as exceedingly poor timing, the friars had entered into another round with the commandant general. At base the issues at odds remained the same—propagation of the Faith and imperial security. In 1799 Pedro de Nava had denied Father Bringas' request to found new missions on the Pimería Alta frontier, largely because they would have sat exposed beyond the presidial cordon. After that, the friars had bided their time. Father Llorens had kept ministering to the heathens as best he could from San Xavier del Bac. By 1805 the college had decided on the site of its first Pápago mission, Santa Ana de Cuiquiburitac, less than fifty miles northwest of the presidio of Tucson. Then in 1809, with the allegedly pro-missionary Suprema Junta Central governing in Spain, the college tried again. They found Nemesio Salcedo no more amenable than Nava. [8] To carry their colors the friars of the college had chosen stubborn, round-faced Fray Juan Bautista de Cevallos, a sixty-year-old ex-guardian whom they had recently named comisario prefecto of missions. The new job gave Cevallos overall supervision of the Queretaran missions, outranking Father President Moyano in the field, and charged him to manage mission affairs with the governments of Sonora and the Provincias Internas. He did not hesitate. Opening with a petition to Commandant General Salcedo in October, 1809, Cevallos had asked permission to found a missionary hospice in Sonora and new missions on the Pimería Alta frontier. Salcedo put the friar off. He wanted opinions from Bishop Rouset and Intendant-Governor García Conde. Confident of favorable replies from bishop and intendant, Father Cevallos had gone off to Mexico City to raise money. By early December he was exultant. Already, he reported to Salcedo, he had enough pious funds for three new missions. If the commandant in his capacity as vice patron of the church would merely issue the license to found these missions, and provide the necessary mission guards, the college could begin at once. That set the commandant general raving. He had better things to do. Since Napoleon's sale of Louisiana to the United States, Salcedo had been hard pressed to hold back the encroaching North Americans. The recent affair of Zebulon Montgomery Pike was but a single case. This matter of Pápago Indian missions had gone far enough. Founding missions beyond the presidial line was folly. Had Cevallos forgotten what had happened on the Río Colorado, even with mission guards? Salcedo offered an alternative, a safer way for the college of Querétaro to expend its Christian zeal and its patrons' money. Why not join with the short handed college of Zacatecas to carry the Faith to the poor Tarahumaras and Tepehuanes deep in the Sierra Madre? That was impossible, Cevallos retorted. The king had assigned the Sonora frontier to the Querétaro college and had forbidden one college to work in another's sphere. Besides, the Pápagos were not dangerous. If the Pápagos were not dangerous, asked Salcedo late in March, 1810, why bother with mission guards at all? At this juncture, the commandant appealed to Bishop Rouset, himself an ex-member of the college of Zacatecas and an ex-missionary to the Tarahumaras. [9] Father Cevallos did not back down. By mid-summer 1810 he had threatened to take the matter over Salcedo's head to the authorities in Spain. Then, writing from Querétaro on September 17, 1810, the day after Hidalgo's grito de Dolores, the friar accused the commandant of deliberate delay. The college had raised funds for not one but a whole series of heathen missions. Salcedo did not have to wait for the bishop's reply: he had the authority himself to found missions. When the bishop did reply two days later, he suggested only that another friar be assigned to San Xavier del Bac to allow Father Llorens time to further examine possible mission sites in the Papagueria. Salcedo was delighted. That ought to hold the pesky Franciscan. When Cevallos' bitter and accusing letter of September 17, 1810, delayed a year by the insurrection, finally reached Salcedo the commandant exploded. How dare he? Would these importuning, impractical friars never learn? They had not solved any of the problems of a Pápago mission. What about water, he chided. The wells and tanks suggested by Father Moyano would not only take most of their money but would also make the government that approved them look bad. What if the Pápagos decided to throw in with the insurgents? There had been rumors. Then he would lose minister, funds, and guard all at once. The commandant trusted that with the extra friar suggested by the bishop the comisario prefecto's ardor for converting the Pápagos—no less, averred Salcedo, than his own concern for souls, circumstances permitting—would cool and leave him free to do his job. "I am convinced that instead of meditating on petitions to Europe, you ought to get on with it, by assigning another missionary." [10] The clamor of the Hidalgo revolt had drowned any reply from Cevallos. The friar waited. Meanwhile, Father Llorens used oxen from San Xavier to haul timber and supplies out to Cuiquiburitac where he and the Pápagos built a chapel, house, and shelters for the escort that accompanied him. [11] Then in December, 1812, more than a year after he had fired off what he hoped was the coup de grace, Salcedo heard again from Cevallos. The testy grayrobe was headed for Chihuahua. With five missionaries and twenty-one mule loads of supplies for the missions, Father Cevallos had set out from Querétaro on November 30. Face to face he would discuss with Salcedo, and with the bishop, new missions and a hospice, then proceed to a visitation of Pimería Alta. He reached Chihuahua on January 22, 1813. Nothing had changed. He still threatened to appeal to Spain. He even went so far as to suggest that he himself would, with Salcedo's approval, recruit volunteers from among retired soldiers as a guard for the first mission. Then Fray Juan Bautista de Cevallos, O.F.M., "Father of the Provinces of Michoacán and Jalisco and of the College of San Fernando de México, Commissary of the Holy Tribunal of the Inquisition, ex-Lector, ex-Guardian, and present Commissary Prefect of the missions of the College of la Santa Cruz de Querétaro," drew himself up to his full height and all but dared the commandant general to deny him. Salcedo did. Not only did the commandant challenge the friar's credentials as comisario prefecto, but he questioned the legality of any innovation whatever in the missions. Were not the friars themselves now resurrecting, at least in part, the very custodies Father Barbastro had labored so ceaselessly to kill? The king's cedulas abrogating the custody of San Carlos had decreed continuance and support of the missions en la forma anligua. Salcedo was unaware that the royal will had changed one whit. Therefore he revoked Father Cevallos' pass to proceed any farther. The friar had been outmaneuvered, for the moment. He had no alternative. He had to turn back to Querétaro. Both men appealed to Spain. The friar had a brother at court. [12] Times were bad, at least unsettled, for everyone. The absolutes of the past seemed bent on crashing down and the future held nothing but uncertainty. For the Querétaro college, allied firmly with Spain's rule in Mexico but estranged from the commandant general, the best prospect for security lay in fraternal unity and integrity. There could hardly have been a worse time for dissension and scandal in the community. The college had sent a recruiter to Spain in 1796. He had dallied. Wars, blockades, and bureaucratic inefficiency hampered his efforts. Not till 1803 did he dispatch the first fifteen friars. Eleven more had followed in 1805. Several of them were soon at work in Pimería Alta without fanfare. The next mission was something else. As Cevallos confided to Father Bringas, "Friend, these new gachupines. . . come with the very latest ideas in religious devotion." [13] Enlisted during the trying three years between 1810 and 1813 when French armies occupied much of the peninsula, the friars of this most recent mission had sailed piecemeal on six different ships. Their colectador, Fray Francisco Núñez, did not depart Cádiz with the last half-dozen until July, 1813. Of the thirty-seven recruits he managed to embark, fully half proved utterly unsuitable. [14] In the winter of 1812-1813 five of the new arrivals had ridden north in the train of Father Cevallos. At Durángo he sent three ahead to Culiacán with a letter for Bishop Rouset. The other two he took with him to Chihuahua to meet Commandant General Salcedo. Although Salcedo forced the unrelenting Cevallos to go back the way he had come, he let the five missionaries pass. By early June, 1813, under the eye of the old guard, they had taken up their ministry, Miguel Montes at Tubutama, Matías Creo at Oquitoa, Pedro Ruiz at San Ignacio, Francisco Fontbona at Cocóspera, and Francisco Pérez at Tumacácori as compañero to Narciso Gutiérrez. Only Miguel Montes lasted. [15] Fray Pedro Ruiz, a chronic complainer, had begged the viceroy from Mexico City, even before he had seen the college, to let him go back to Spain where he could be more suitably employed "or defending with the sword our beloved religion as I had done before for a year and a half." Father Núñez, he claimed, had misrepresented the situation in New Spain. "He told me that I did not know the character of this people, that they very much wanted us, and even should the insurgents prevail the convents would remain in existence. He told me that by the time we arrived here this would have quieted down. What has happened is just the opposite." Besides, his stomach ached. [16] At Tumacácori the thirty-year-old Francisco Pérez decided he would rather be a presidial chaplain than a missionary to Indians. Born in the villa of Rubielos de Mora a long day east and south of Teruel, he had entered the order on November 23, 1800, and sailed for America September 6, 1811. Pérez and his fellow Aragónes Pedro Ruiz had given Father Cevallos a hard time on the road north from Querétaro with their little attention to the daily offices. When the superior threatened to send them back to the college they humbled themselves half-heartedly. He decided right then, as much to get rid of them as to use their services, that they and Matías Creó should carry the letter to Culiacán for the bishop. [17] Fathers Gutiérrez and Pérez did not see eye to eye, which may not have been all Pérez' fault. The older, entrenched Gutiérrez had been painfully afflicted by what sounded like a severe case of the shingles. "For two years now," Father President Moyano wrote in September, 1813, "Father Narciso has suffered from sores over almost all his body. Some clear up and others follow, and thus afflicted he continues coming and going without ceasing his ministry but not fully cured of them even though he has tried various remedies." That cannot have brightened his disposition. Evidently Gutiérrez turned over to his irreverent new compañero the spiritual care of Tubac. That proved a mistake. [18] Meanwhile back at the college, the headstrong Father Cevallos savored the news that Nemesio Salcedo had retired. No one would stop him now from performing his duties as comisario prefecto of missions. Another of the periodic reorganizations had split the Provincias Internas into eastern and western divisions. In November, 1813, Cevallos applied to the elderly don Bernardo de Bonavia y Zapata, commandant general of the west with headquarters in Durango, for permission to carry out his delayed visitation. Bonavia consented, and by the following spring the indomitable old Franciscan was in Sonora. After a visit to Arizpe he decided that his pet project, the missionary hospice, should be located not there in the capital but in Ures. Soon Commandant General Bonavia began getting petitions from interested citizen groups. He had given this friar a license to conduct a visitation, not run around soliciting support for a hospice. That matter would be decided in Spain. Annoyed, Bonavia dictated a letter to the acting governor of Sonora. "If these petitions persist, interrupting the important affairs of this office, I shall find it necessary to order Father Cevallos' return to his convent whether or not he has concluded his visitation." [19] On the matter of missions for the heathens the new commandant general blew hot and cold. "It is not possible at present," he had written in January, 1814, "to provide the aid requested for founding the missions proposed on the Gila River and at the place called Santa Ana." Still, he wanted to know what preliminary measures might be taken to insure a fruitful reception of Christianity among these Indians. He pondered technical assistance, settlers joining with the heathens in farming and ranching operations thereby starting them along the road to civilization. [20] A crisis had developed at San Xavier del Bac where Father Llorens had been working with and encouraging the heathens for more than twenty years. Some of them, evidently provoked by gente de razón from Tucson, had rebelled. Utterly dejected, Llorens was asking for his superiors' permission to join the province of Jalisco.

At the same time Indian delegations from the Gila trooped all the way south to Arizpe to demonstrate before provincial authorities their desire for missions. A Cocomaricopa chief with nineteen of his tribesmen showed up toward the end of January representing four pueblos. In late March a large Gila Pima embassy stopped by the presidio of Tucson for a pass to the capital. These Indians admitted that the drying up of the river in 1813 and resultant crop failure—in which they claimed to see the hand of God—had motivated them. When word of these heathen demonstrations reached Commandant General Bonavia in Durango, he asked for an informed opinion. [22] Captain Antonio Narbona, seasoned commander of Fronteras, hero of the great Spanish victory over the Navajos in 1805, and temporarily directing operations from Tucson against the Apaches, had no use for the Cocomaricopas. They and the faithless Yumas were one and the same; they had tried to kill the people he had licensed to trade with them; they could not be trusted.

The Gila Pimas, who had not ceased their pleading for baptism, were different, said Narbona. They deserved missions. But they would also have to have a presidio, to ward off nearby Tonto and Pinaleño Apaches. Captain Narbona knew how this could be provided without additional expense. The settlers at Tubac and along the middle Santa Cruz, together with the Indians of Tumacácori, could defend themselves. The Pima company of Tubac, now under the acting command of Ensign Juan Bautista Romero, could thus be moved to the Gila. [23] Again Father Garcés would have smiled. The Spanish constitution of 1812 and the visitation of Fray Juan Bautista de Cevallos converged in Pimería Alta in 1814 to the extreme discomfort of Narciso Gutiérrez and most of his fellows. If Cevallos was not, like Reyes, a reformer at heart, he had at least resolved to go along with the new constitutional regime. In the missions, that meant the election of alcaldes nacionales; the payment of wages to any Indian for any job from herder to catechist not done for his own sustenance; and the allotment of farm land, first to mission Indians, next to the recently converted, and last to settlers. All this had the ring of the 1767 Croix-Gálvez instructions to the missionaries. The issue had not changed: it was still a question of how much authority the missionary should exercise over his Indians. The traditionalists argued in favor of absolute paternalism, for the poor Indians' own good. The reformers called it despotism. In the opinion of most of the friars in the field, Cevallos had gone over to the side of the misguided liberals. Arriving on May 14, 1814, at Cocóspera, the Father Commissary Prefect was pleased to find that Fray Francisco Fontbona had already complied with the new regulations. Moreover, the mission appeared prosperous, both physically and spiritually. Fontbona had served Cevallos as secretary in 1813 on the road from Querétaro to Chihuahua. The superior admired the young catalan's precision and his willingness to obey the new law. Again he recruited Father Francisco as his secretary. Later Fontbona would claim that because he had assisted Cevallos during the visitation, he had incurred the undying hatred of many of his brethren, from Father President Moyano on down. [24] When Cevallos and Fontbona dismounted at Tumacácori in late June they had already inspected six of the missions. They had tried to explain to the Indians what the constitution of 1812 meant to them, and they had counseled unwilling friars to obey the law. Though there had been grumbling, Father Cevallos felt confident that he was firmly instituting the new order. Like Father Visitor Bringas twenty years before, Cevallos took a dislike to Narciso Gutiérrez. He had heard rumors about the long-time Tumacácori missionary's un-Franciscan commercial activities and temporal irregularities. If a suitable replacement could be found, he recommended the removal of Father Narciso. [25] On paper the 147 Indians and mixed-breeds of Tumacácori were per capita the richest mission residents in all Pimería Alta, though according to Cevallos they lived in poverty. He noted that Tumacácori possessed 5,000 cattle, 2,700 sheep and goats, 750 horses and mules, and 5,654 pesos, surely what was owed the mission, not cash on hand. Only San Xavier del Bac, with the visita of Tucson and a combined population of 578, had more cattle (8,797) and more money (6,293 pesos). The Father Prefect did not comment on Tumacácori's unfinished church. [26]

Before Cevallos rode on to San Xavier, last of the missions, he had a long talk with Fray Francisco Pérez. The young compañero charged by Gutiérrez to look after the presidio had done more than that. He had got in a fight with Tubac's alcalde nacional "from which arose many scandals." The aggrieved official had twice appealed to the Father Prefect to punish the wild friar, threatening that if he did not receive satisfaction he would have recourse to the government. "Seeing no other way to quash the scandals that had occurred already and avoid other worse ones that threatened," Cevallos wrote to Father Guardian Bringas, "I persuaded Father Pérez to ask me for a license to return to the college." That satisfied the alcalde, and on June 28 Francisco Pérez left Tumacácori. [27] But the independent friar had other ideas. Instead of taking the shortest route to Querétaro, as he was supposed to, he traveled around looking for an opening as a presidial chaplain. When that failed he talked his way into an interim vicariate of an Indian pueblo in the diocese of Mesquital. Later Cevallos discussed the case with the commandant general and the episcopal deputy. Both agreed to suspend Pérez and order him to comply with his superior's dictum. At that point Pérez dropped from sight. [28] Hardly had the Father Prefect concluded his visitation when momentous news arrived from Europe. The French had been driven from Spain. Napoleon had set Ferdinand VII free. And in May of 1814 the Spanish king had reasserted himself, suspending the constitution of 1812 and all the laws of the constitutional regime. One such law awaiting action in Mexico City called for the immediate secularization of all Indian missions over ten years old "without any excuse or pretext." Now a bureaucrat simply made the notation: "Suspended . . . because it is a resolution of the Cortes, pending what our Sovereign don Fernando VII pleases to resolve in the matter." [29] Most of the missionaries rejoiced and shouted with the crowd Viva el Rey! When he looked back on the visitation nearly four discouraging years later Father Cevallos painted a dismal picture for the viceroy. In all the Pimería he had found only two friars with any understanding of the Indians' language. This sad lack might have been mitigated by teaching the Indians Spanish, but there was in the missions not a single elementary teacher. And because the missionaries did not exercise proper supervision over the madores, or Indian catechists, much of what these helpers taught was utter gibberish. It would be good, thought Cevallos, to settle gente de razón of solid character in the missions, but some friars would not concede them the means to make a living. In these missions, over a century old, he had found natives ignorant of Christian doctrine and Spanish but well schooled in "superstitions of heathendom." Every one of the missions, Cevallos alleged, could afford to provide decently for the Indians. Yet he noted "that the ministers of the richest missions were the most at fault." Almost everywhere he had seen the Indians poorly housed in adobe hovels "where men, women, sons, and daughters all slept together." Their diet and clothing too he judged substandard. [30] The veteran missionaries concurred. Matters went from bad to worse after the Cevallos visitation. It had served for no other purpose, Gutiérrez asserted in the spring of 1815, than "to make the Indians insolent and give them freedom for drunks and sinful living." Morale was at a low ebb. "I think there must be few among the old-timers who want to continue in the missions." When Father Narciso's license to retire to the college arrived at Oquitoa, a tired and disconsolate Father President Moyano hid it so that he would remain at Tumacácori. But Gutiérrez knew and rode over to inquire. The old superior begged him to stay on. At San Xavier del Bac, Juan Bautista Llorens still asked to be released to the Jalisco province. He would stay in Pimería Alta if the superiors would transfer him to Tumacácori with Gutiérrez. But the contempt and aversion of his Pápagos at San Xavier was too much for him to take—"from Indians I had brought with my sweat from the desert to a knowledge of God and supported them in their needs with more love than if they had been my own children." [31] They hated the new permissiveness, the scandalous abandon of the recent arrivals, and the jokes being told at the presidios by "the coarse and ignorant." "Corruption has come among us with this last shipment," wrote Gutiérrez, "the cause that fills us old ones with grief while the new ones are very cocky." Father President Moyano was desperate, literally afraid for his life. During the past Christmas season he had attempted to correct fraternally his compañero Fray Matías Creó. Instead of humbly accepting his superior's counsel, Creó "called him damned, vile, shit, and other things that cause horror." Seeing murder in the young friar's eye, the Father President departed for Ati. The whole incredible and sordid affair came to a head a few days later when the psychotic Creó attacked Moyano at Ati with a knife before a large crowd. Disarmed and tied up, he continued to spout blasphemy, even as they hauled him away. The shame of it all made Father Gutiérrez want to sneak away in the night, "for what the eyes do not see the heart does not lament." The scandals of 1815 were too sensational to contain in Pimería Alta. Father Matías Creó filed charges with the commandant general against the lieutenant who had dragged him away from Ati. Father Francisco Fontbona denounced don Fernando Bustamante, commanding officer at Santa Cruz, and as a result the commandant general removed that officer. In the judicial review that followed Bustamante's partisans had no trouble dredging up scandal about Fontbona and his buddy Fray Pedro Ruiz. "In this day," lamented Gutiérrez "our habit will not escape becoming the broom of the General Command." [32] In desperation the superiors at Querétaro appealed to the controversial trio—Creó, Fontbona, and Ruiz—to return voluntarily to the college. They refused. When Fray Ángel Alonso de Prado took over once again as Father Guardian from Fray Diego Bringas in 1815, he ordered indictments drawn up in Pimería Alta against the three. He then sent Bringas to Durango to treat with Commandant General Bonavia. Just as soon as the indictments reached Father Bringas he was to present them to the commandant general and beg that the offending friars be exiled to Spain via the port of Altamira, two hundred and fifty miles north of Veracruz, and not be allowed to set foot in the college. "They are," wrote Prado, "arrogant, insubordinate, and in my opinion capable of any offense." [33] The college asked a friar of the Jalisco province, Father Fernando Madueño of Cucurpe, to act as judge in preparing the indictments. In December of 1815 and January of 1816 he heard a succession of witnesses recount the Creó-Moyano confrontation and the loose living of Fontbona and Ruiz. The chaplain of the Altar garrison described how the latter two Fathers had led a whole crowd of men and women on horseback out into the countryside on a wild picnic. They drank, sang, and had a generally gay, goyesque time of it. Fontbona sang the verses of Amor, Amor "with gesticulations." Don Francisco Redondo, who could not believe such dissipation in Franciscan Fathers, left in disgust. That night the revelers went by his house to chide him, "telling him that he was a Jesuit." A corporal from Altar testified under oath how Fontbona loved fandangos, boleras, and brandy. A barrel of aguardiente did not last him a month! Every one knew of his affair with the woman Luz Durán alias Sastra, and his notorious drunken brawl with "el zapatero tapatío." All day Thursday, Friday, and Saturday of holy week the friar had shut himself up with a few soldiers and settlers and gambled at cards. The wife of a Santa Cruz corporal away since the outbreak of the insurrection lived in the Father's house at Cocóspera. Scandal begat scandal. [34] None of the accused was apprised of the charges against him or permitted to testify in his own defense, but they knew what was going on. Pedro Ruiz fled. Embarking on a China ship at Guaymas on Christmas Day, 1815, he traveled to Acapulco, from there to Querétaro, and then let himself be sent back to Spain. Fontbona and Creó held their ground for more than a year. While the indictments against them were being considered successively by the commandant general in Durango, the audiencia in Guadalajara, and the viceroy in Mexico City, they appealed. "If there are new laws," Fontbona wrote to the viceroy from Cocóspera, "that condemn men without hearing them, that convey them to execution without telling them for what crimes, then my Father Guardian has inflicted them on me to the letter." He lashed out at his brothers, his "rivals," "the dominant group that has plotted against me as a means of revenge." Their conduct, he alleged, was worse than his. Father Narciso Gutiérrez of Tumacácori, whom Fontbona wrongly suspected as his accuser, had earned a reputation "as the friar userer of this province and much more by his acts of lewdness." As proof he submitted an unsigned document, allegedly in the hand of Fray Gregorio Ruiz who had served at Tumacácori with Gutiérrez and then at Cocóspera. Its author lamented the excesses of the missionaries. As an example of their blatant commercialism, he told how on Christmas Day of 1808 the pack train of Father Gutiérrez had passed through Cocóspera loaded down with everything from spurs to chilies on the way to trade in Ópata country. Far from preventing this and other abuses, the Father President railed at those who dared criticize. One young friar had been badly mistreated by his seniors for bringing up to Father Joseph Pérez at San Ignacio the rule against allowing women in the friars' quarters. Pérez, it seemed, had hired as cook an extremely beautiful young woman "whose glance alone can prejudice the virtue of chastity." [35] Though Fontbona and Creó failed to save themselves from exile, they did a thorough job of sullying the reputation of the college. They forced the superiors at Querétaro to deny their charges. When the viceroy forwarded to the college copies of Fontbona's slanderous attack, Guardian Prado felt obliged to answer point by point. As for Father Narciso Gutiérrez, he had taken no part in the proceedings against Fontbona.

Late in May, 1817, after the homicidal Creó had threatened the new Commissary Prefect Joseph Pérez with a knife, he and Fontbona took off under cover of darkness. Arrested at Guajoquilla south of Chihuahua, they were taken under guard, protesting and appealing all the way, to Durango and from there to San Luis Potosí. Finally on January 21, 1818, Viceroy Juan Ruiz de Apodaca, ordered them sent "with the appropriate security and decorum" to Altamira for shipment to Spain. The same day he admonished the Father Guardian of the college at Querétaro to send to Pimería Alta in the future only the most exemplary, virtuous, and prudent friars. The case was closed. [37] At Ures, ex-commissary prefect Juan Bautista de Cevallos had all but given up. Though the restored Ferdinand VII had authorized his missionary hospice and the three new missions—since they were to cost the crown nothing—Cevallos had no more to show than an extensive, hollow foundation. His benefactors had closed their purses. His brethren opposed him, even denounced him to the commandant general. Narciso Gutiérrez, for one, branded the hospice a useless extravagance. Santa Ana de Cuiquiburitac had been scrapped as a mission site allegedly for lack of water. No volunteers could be found to serve as guards in new missions. They feared a repeat of the Yuma massacre. In the spring of 1818 a dejected Cevallos informed the viceroy that he had turned over all the pertinent documentation to his successor. He wanted the viceroy to know, in hopes that some contribution might still be made "to the service of both Majesties, the welfare of these provinces, the conversion of heathens, and the defense of the honor of this poor religious, so old and persecuted, who now can do no more." [38] Father Cevallos did not give up on the hospicio. In February, 1826, nine months before the old friar died, an Englishman visiting Ures noticed a church with a building attached. The only resident was Cevallos, tall, still erect, his beard and hair white, who explained that the building was "a Hospicio, or receptacle for aged and infirm friars" and invited the foreigner in. His guest had no reason to doubt that the Franciscan was "upwards of ninety" for he "wore upon the whole a very venerable appearance." They talked about Sonora. The friar maintained that progress would have been more rapid had the Spanish government never expelled the Jesuits. Cevallos impressed the visitor as well educated and extremely understanding of the local people. The Englishman did not want to take his leave, rather he wished he could have "spent a day with this living chronicle of olden times." [39] The monthly post returns from Tubac for 1817 and 1818 belied the government's boast that the insurrection was dead. Of the Pima infantry company's sixty-three officers and men shown on January 1, 1817, twenty were still on duty in the south:

The troops who remained on duty against the insurgents received, in addition to specific bonuses, double service time on their records, as per the royal decree of April 20, 1815, "which was extended for the troops of this province." The other forty-three members of the garrison were disposed as follows:

Carried on the rolls in addition were thirteen inválidos, retired soldiers settled at the presidio and on call for emergency duty. All of them were present. One soldier, Antonio Trejo, had deserted on Christmas Eve, 1816. [40] Lieutenant Ignacio Elías González, forty-two, born in Chinapa of a prominent Sonora family, was not present once for muster at Tubac during 1817 or 1818. He spent most of his time at Arizpe. Named commander of the Pima company on December 20, 1814, at seven hundred pesos a year, he had served previously as soldier at Fronteras, cadet at Altar, ensign at Buenavista, and lieutenant at Santa Fe in New Mexico. Alejo García Conde, who replaced Bonavia as commandant general late in 1817, evaluated Elías as an officer of proven valor, sufficient application, sufficient capacity, average conduct, and married. "He has been a regular officer, but at present he is being prosecuted in the bankruptcy of the paymaster's office of the Santa Fe company." The acting post commander, sixty-three-year-old Ensign Juan Bautista Romero, had been born at Tubac on San Juan's Day Eve, June 23, 1754, and baptized a week later by the Jesuit missionary of Guevavi. His parents, don Nicolás Romero and dona María Efigenía Perea, owned the Buenavista ranch. Don Juan's entire military career, forty-two years, had been spent in Hispanic Arizona at Tubac and Tucson. He retired in August, 1818. Up to the end of 1817 he had taken part in twenty-eight campaigns, twenty-five forays, and the defense of Tucson against "the principal attacks" of the Apaches. García Conde rated his qualities: valor, known; application, little; capacity, scant; conduct, good; marital status, widower—in sum, "regular in his class." [41] José Rosario and Inocencio Soto, addressed as don in the manner of gentlemen and officers, were classified as oficiales de naturales. As such they enjoyed a certain social mobility. On February 2, 1818, Fray Narciso Gutiérrez married don José, "Lieutenant of the Pima nation," to doña Manuela Sotelo, daughter of the deceased don Ignacio Sotelo, evidently a "Spaniard." Soto, an Ópata, had enlisted at Tubac twenty-four years before, in 1793, when he was described as 5' 3", with "black hair, broad forehead, and Roman nose, pock-marked, swarthy, and beardless." [42]

In January, 1817, Ensign Romero enlisted a Tumacácori Indian. The entry in the Pima company's register was standard:

Romero then certified that the Indian had signed up voluntarily with full knowledge of the penalties for desertion and surrender. [43] Another native of Tumacácori, Juan Antonio Crespo, dark-skinned, beardless, with black hair, black eyes, a broad nose, and a scar over his left eyebrow, was able to enlist in the better-paying cavalry company at Tucson in May, 1819, probably because he was by then thoroughly hispanicized. His mother, María Gertrudis Brixio, had been listed as either a Yaqui or an Ópata; his father, Juan Antonio senior, as a Pima, killed outside the walls of Tumacácori in June, 1801, a manos de los Apaches. [44] Father Joseph Pérez, Cevallos' successor as comisario prefecto, was an unrelenting pessimist. Surrounded by ignorance, sickness, and want, he saw little hope for progress, spiritual or material, in Pimería Alta. Writing from San Ignacio in 1817, one hundred and thirty years after the Jesuit Eusebio Francisco Kino first spoke of the Christian God in that place, Pérez lamented the Indians' failure to accept Him:

When heathens came into the missions to be catechized, said Pérez, hardly did they receive baptism before they got sick, their women went barren, or their children died. In one of his pueblos, he asserted, not a single child reached maturity in eleven years! In August of 1816 a terrible peste epidemia had ravaged the missions. He and two other priests worked ceaselessly administering the sacraments in the pueblos of San Ignacio until they themselves fell ill. The epidemic spread north slowly. Not till mid-October were its fatal effects felt at Tumacácori. Then in the next two months Narciso Gutiérrez entered twenty-five names in the mission book of burials, fifteen of them children's. [46] The college had sent not a habit in four years. "We are dressed," wrote Pérez, "in poor coarse cloth and wrapped in blankets." The government had ceased paying the annual mission stipend three years before. At the same time the troops demanded provisions, cattle, and horses. "They make forced loans from us continually." At least the mission sacristies were well supplied and the churches decent "except for Tumacácori's which years ago was begun of stone and brick. Construction is halted perhaps because of the ill effect of the insurrection." [47] The next year, 1818, Tumacácori produced only 150 fanegas of wheat, none of maize, 40 of beans, and 2 of garbanzos. The population stood at 105 Indians and 35 Spaniards and half-breeds. Bread then was scarce. Twenty years earlier, when the total mission population numbered just over one hundred, 200 fanegas of wheat was considered minimal. Meat remained plentiful. Tumacácori still had an estimated 5,000 head of cattle, 2,500 sheep, 600 horses, 89 mules, and 15 donkeys, making it overall the richest of the missions in stock. But there was no market. "Because of this and the lack of water," Father Pérez explained in his annual report for 1818, "the stock has left the environs and limits of the missions: to round it up is expensive and the products do not cover the cost." All over the Provincias Internas during the insurrection years people suffered in the economic crisis. Specie went out of circulation. In Pimería Alta clothes and goods served as money. The sales tax imposed throughout the Provincias Internas, and for the first time applied to mission Indians, added to the woes of the poor. Mission industry foundered for want of cash to pay skilled labor and buy tools. Even the gifts customarily given to the heathens had been discontinued. Little wonder work on Father Narciso's church had stalled. [48] Nor did politics or Indian relations give cause for optimism. At the provincial level the government seemed helpless to cope. Some criollos spoke openly of Mexican independence. They were heartened by news that a handful of seaborne Argentine insurgents had captured the capital of Alta California late in 1818. The government worried that communications from Guaymas in Sonora across the Gulf of California to Loreto would be severed. When a detachment of Ópata auxiliaries was ordered to embark at Guaymas as an escort for the mail the Indians refused and were arrested. In protest their brothers at the presidio of Bavispe mutinied and held the post for more than a week. A courier passed through Tumacácori in February, 1819, carrying word that the Apache warrior Chilitipagé and ninety-two of his band had presented themselves at the presidio of Tucson and asked for peace. Two months later Father Narciso buried in the Tumacácori cemetery forty-year-old José Miguel Borboa, killed by Apaches. [49] From the time Narciso Gutiérrez buried his predecessor in 1795—during the troubled reign of Carlos IV and the second administration of George Washington—until he took to his bed for the last time in November of 1820—the year of the liberal revolt in Spain and the Missouri Compromise in the United States—Tumacácori's most enduring friar, his temporary replacements, and his companeros recorded in the mission books some 255 baptisms, the same number of burials, and 97 marriages. [50] Long since devoid of the human pathos that surrounded these events, the bare facts still serve. For the first time in half a century a Tumacácori missionary ended his tenure having baptized as many persons as he buried. Father Narciso neither lowered the mortality rate nor attracted appreciably more heathens. His even ratio resulted from an influx of population, mainly non-Indian or at least non-Pima and Pápago. Gente de razón entered the valley in increasing numbers during the first two decades of the nineteenth century, not at a constant rate but when conditions dictated. Some settled at the mission in preference to Tubac, which also grew during these years. No matter how poor, they wanted servants, and Gutiérrez baptized for this purpose more Apaches and Yumas than ever before. Yaquis, fleeing oppression in their pueblos to the south, also came to work for the mission and the settlers. Just before he died in 1820, Gutiérrez listed Tumacácori's population at 121 Indians and 75 Spaniards and persons of mixed blood. [51] After Father Narciso had secured the mission lands by title in 1807 he encouraged settlement. By 1808 several gente de razón families had reoccupied Calabazas, which Gutiérrez called thereafter the mission rancho. Evidently they did some restoration, for on May 5, 1818, the friar celebrated a marriage in the Calabazas church. Farther south at Guevavi a sizable mining operation, employing Yaqui labor, had commenced in 1814. From the number of baptisms, marriages, and burials he performed for "Yaquis de Guevavi," there must have been dozens of them. There had been gold mining there sixty-five years earlier, and there would be thirty-five years later. [52] Doubtless Father Narciso saw that the mission got a share of the yield. Of the 255 persons whose burials he entered in the mission book, 65 were infants under age two, 50 were children two to fifteen, and 140 were adults from sixteen to "one hundred or more." That ratio had changed little. Three of the four persons Father Narciso claimed were centenarians, the censuses rejuvenated by thirty to forty years. When his entries are compared with those of other friars who served at Tumacácori, it appears that Narciso Gutiérrez was unusually reluctant to administer viaticum, or final communion, to dying Indians. Either they did not summon him in time, or they were choking or vomiting. Some friars more than others plainly doubted the Indians' capacity. Narciso Gutiérrez talked of going home to Spain, even of making a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, but he never did. [53] He had endured more than double the compulsory ten years. Still he chose not to use his license for the college. In deference to Father President Moyano, who never really recovered from his ordeals with the new liberal generation, Gutiérrez did not abandon the Pimería. The older men were dying off. Juan Bautista Llorens, who looked back at glorious San Xavier del Bac with a broken heart, had died on the road at the presidio of Santa Cruz in 1815. Little over a year later Narciso Gutiérrez buried Fray Gregorio Ruiz, Llorens' successor at San Xavier. In 1817 word came from the college that former Father President Francisco Iturralde had expired on Easter eve, three days short of his seventy-fourth birthday. Moyano himself followed nine months later. When Gutiérrez' time came, Wednesday, December 13, 1820, the blue-eyed friar with the long nose died alone and unprepared, without the holy sacraments. He was not ancient, only fifty-five, twenty years younger than Pedro Arriquibar, whom he survived by less than three months. They carried the body of Narciso Gutiérrez in a wooden box past the open walls of the temple he had begun nearly two decades before and into the narrow little adobe the Jesuits had built before he was born. On Friday morning they put the box into a hole dug "beneath the steps of the main altar on the Epistle side." They did not even record the burial. Father Narciso's successor could take care of that. [54] Narciso Gutiérrez was spared the trauma of Mexican independence, but just barely. On his deathbed he could recall the bishop of Sonora's admonition to his clergy: Jesus Christ had taught, and the holy scriptures reiterated over and over, the obedience owed to a legitimate sovereign. And Ferdinand VII was legitimate sovereign of all the Americas. Gutiérrez knew that Intendant-Governor Antonio Cordero had taken personal command of government forces at Rosario in southern Sinaloa, and that by late 1820 he had finally harried the insurgents out of the rugged green mountains and barrancas in the area. [55] But the Spanish friar also knew before he died that Ferdinand VII was in serious trouble at home. A liberal revolt had forced him to restore the constitution. He was practically a prisoner in his own palace, with atheists and Freemasons dictating policy through a radical Cortes. Dutifully, the bishop and the intendant-governor of Sonora had obeyed the royal instructions requiring an oath to the constitution, knowing full well that they did not reflect the royal will. One of Gutiérrez' last acts was to sign in a wobbly hand the episcopal circular proclaiming anew the Spanish constitution. He did not live to see the result. [56] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

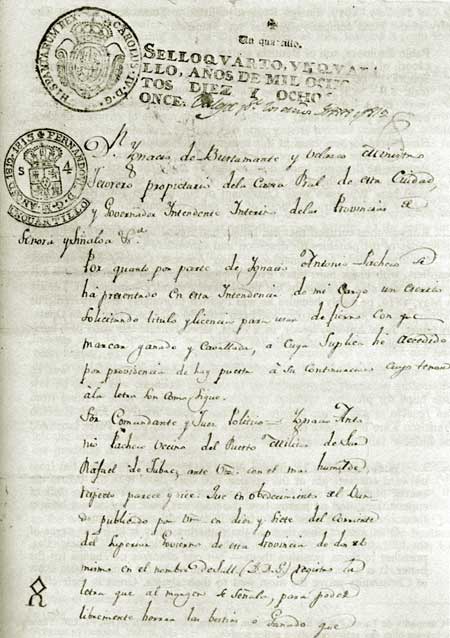

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||