Contents Foreword Preface Jesuit Foundations Gray Robes for Black 1767-68 The Archreformer Backs Down 1768-72 Tumacácori or Troy? 1772-74 The Course of Empire 1774-76 The Promise and Default of the Provincias Internas 1776-81 The Challenge of a Reforming Bishop 1781-95 A Quarrel Among Friars 1795-1808 "Corruption Has Come Among Us" 1808-20 A Trampled Guarantee 1820-28 Hanging On 1828-56 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

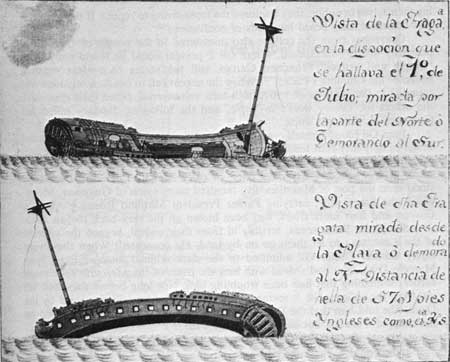

THE LITTLE TWENTY-GUN FRIGATE, Mercurio, from stem to sternpost no more than ninety feet, drifted placidly with the current in the warm sun somewhere southwest of Cuba. The voyagers aboard almost forgot the hell that lay behind—the dark, close quarters sloshing with bilge; the foul, suffocating stench of vomit; cold, worm-infested food; the terrible shuddering; and the wild ceaseless rolling and pitching. Separated from Júpiter, her twin and consort, Mercurio had ridden out the storm and made Havana for repairs. Her overbearing captain, don Florencio Romero, had insisted that she sail on as soon as able, despite the autumnal equinox and the warning of Cuban officials. Now on October 9, 1763, seventy days out of Cádiz, the Mercurio was becalmed. Passengers lounged on deck. Fray Juan Crisóstomo Gil de Bernabé and the other ten friars aboard prayed for their brethren on Júpiter, not knowing that they were safely ashore on Puerto Rico, where their captain had wisely chosen to wait out the equinox. That night Mercurio's watches, lulled by the apparent motionlessness of their ship, came to only with the sudden jolt and awful scraping as she ground onto a reef and rolled over on her starboard side. [1] During the weeks that followed the castaways experienced another kind of hell—exposure, hunger and thirst, and disease on an uninhabited beach. The wreck lay a mile and a half offshore, just what shore no one knew. Captain Romero set some of his crew to collecting the crates and barrels washing up on the beach; others he sent scouting for help. All hands had survived, but now a burning fever descended upon them. According to his brothers, one of the Franciscans, Fray Juan Gil, fought off the disease and selflessly ministered to the sick and dying. There on the beach in cluttered shelters of crates, drift wood, and canvas, he proved his calling. [2] Later the chronicler of the missionary college at Querétaro would portray Fray Juan Gil as "of handsome and manly countenance, pleasing and melodious voice, gentle yet vigorous disposition, natural and forceful persuasiveness, and a fitting and honest keenness of mind that enhanced these gifts with holy erudition and perfect moderation, permitting him to propound Christian doctrine with solid reasoning and no other end than the glory of God and the well-being of souls." [3] The port authorities of Cádiz had seen the friar in a harder light: "tall, slender, round-faced, swarthy, with heavy black beard, curly hair of the same color, and small eyes." [4] At age thirty-five the oldest member of the mission of 1763, Father Gil was from Aragón, from the Villa de Alfambra, a cluster of tile-roofed rock houses set against bare red hills a long day's walk north of Teruel. [5] He had moved early in life north over the mountains to the venerable city of Zaragoza, perhaps to live with relatives. [6] There in 1746 at the age of seventeen or eighteen he entered the Franciscan seminary of Nuestra Señora de Jesús. [7] Predisposed to things of the spirit, and thoroughly convinced of the weakness of the flesh, the lanky lad from Alfambra embraced the life of a religious with his whole being. "I met him when his Reverence was studying theology in the convento where I was a novice," recalled another friar some years later.

Sometime after his ordination Gil had abandoned the comforts of the big-city convento. Seeking a more austere environment and a stricter life of prayer and penance, he set out for one of his order's mountaintop retreats north of Zaragoza. At the outskirts of the Villa de Luna he turned east as pilgrims had for centuries, crossed a weathered Roman bridge, and climbed the lone mountain called Monlora. The view from above was breathtaking. Below on every side stretched the area known locally as the Cinco Villas, a gently rolling, complex patchwork of wheat fields, orchards, and pastures radiating from miniature villages whose buildings blended together except for the churches.

In the severe, fortress-like stone monastery atop Monlora, the grayrobes of a Franciscan recollect community lived their ordered, meditative lives and cared for one of the countless Spanish statues of the Virgin revealed to shepherd boys during the Christian Reconquista. Here where a crucifix reportedly bled and spoke to a brother, Fray Juan Gil, the missionary-to-be, had prayed, mortified his body, and nurtured his soul. [9] Late in 1762 word from Mexico intruded. A pair of friars from the missionary college of Querétaro, one of them a former professor of theology at the University of Zaragoza, were traveling from convento to convento recruiting. With letters they reached even Monlora. They told of the scrupulous communal life within the college and of the staggering challenge outside—throngs of believers wallowing in sin, whole heathen nations utterly ignorant of their Redeemer. [10] Juan Gil begged to go. On January 15, 1763, he strode down the mountain, his travel order for Cádiz tucked in the folds of his habit. [11] Two days south of Zaragoza he picked up another friar bound for the missions. Aside from the bonds of their mutual estate, the two men had little in common. Gil, sophisticated, eloquent, effusive, insisted on witnessing to the beauty of his calling at every convento where they stopped for the night. Instead of taking in the sights of Madrid he devoted himself to spiritual exercises. In contrast, his young, newly ordained companion betrayed at every turn his down-to-earth peasant origin. Plain, taciturn, unrefined, Fray Francisco Garcés preferred the company of simple people. Yet in the missions Gil and Garcés would be neighbors. [12] The government had granted to the college of Querétaro a mission of twenty-four priests and two lay brothers. As was customary, the royal treasury paid for their recruitment, outfitting, and travel. After several months' wait the group had sailed from Cádiz on August 1, 1763, four priests short of the quota, bound for Veracruz. Father Garcés, eleven other recruits, and the padre colectador, Fray Joseph Antonio Bernad, had passage on the Júpiter. Juan Gil and nine others, shepherded by Bernad's ruddy-faced little assistant, Fray Miguel Ramón Pinilla, rode with the ill-fated Mercurio. [13] Ten days after the wreck of the Mercurio, the feeble Captain Romero learned their location, a beach called Petempich on the windward shore of Yucatan. At once he and his purser wrote urgent pleas to the officials at the port of Campeche requesting boats, gear, ship's carpenters, caulkers, and divers for the salvage operation, and provisions for the sick, half-starved survivors. The captain then dispatched his second mate in the ship's boat and sat down to wait. [14] The arrival of Mercurio's launch at Campeche set off a well-rehearsed operation. Within three days five boats made for the scene of the wreck. A lieutenant, a sergeant, and twenty soldiers were dispatched. The governor in Merida alerted coastal villages to send canoes and men. By mid-November the beach resembled a bustling town. The major objective, short of floating the disabled frigate, was getting to shore a thousand containers of the king's quicksilver. [15] Captain Romero and the purser, who both died on the beach, were charged posthumously with smuggling when certain barrels labeled almonds, a cask marked vermicelli, and even the captain's mattress were found to contain cinnamon, playing cards, silks, lace, and ladies' stockings. [16] The Franciscans along with their distinguished fellow castaway, the prosecuting attorney designate of the Mexican Inquisition; Mercurio's register; the royal mail, including the text of the final treaty with Great Britain; six hundred and sixty barrels of liquor, mostly brandy; and other salvage were put aboard the bilander Don Carlos Tercero and on December 3 safely reached Campeche. [17] Giving thanks to God for their deliverance, the fatigued friars, all of whom survived, consented to preach a home mission to the residents of that tropical port before sailing on to Veracruz. [18] Early in 1764, about the time they finally arrived in Querétaro, billows of smoke rose from the wreck of the Mercurio. Unable to float the broken hull, the salvage team had set her afire to recover the hardware. [19] The exemplary Fray Juan Gil, spared in the wreck of the Mercurio, tested himself among the faithful for three and a half years. Because of his fervor, his commanding yet humble presence, and his talent for preaching, he was a natural for home missions, those whirlwind spiritual assaults meant to put the fear of God and the love of Christ into the hearts of complacent sinners. At the request of the presiding bishop a half dozen zealous friars would set out afoot for some predetermined area, not uncommonly hundreds of miles from Querétaro. They might be gone for six months. In town after town, preaching fervorinos on street corners, singing hymns, leading processions, and scourging themselves in public, they implored the loose-living to repent. If their harvest was bountiful, they heard hundreds of confessions. [20]

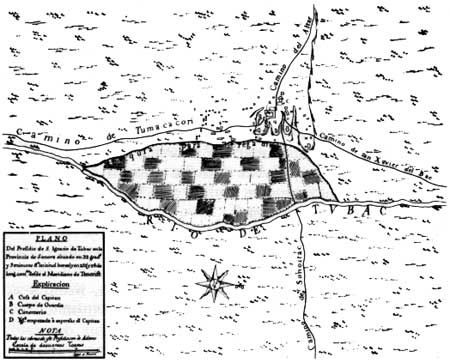

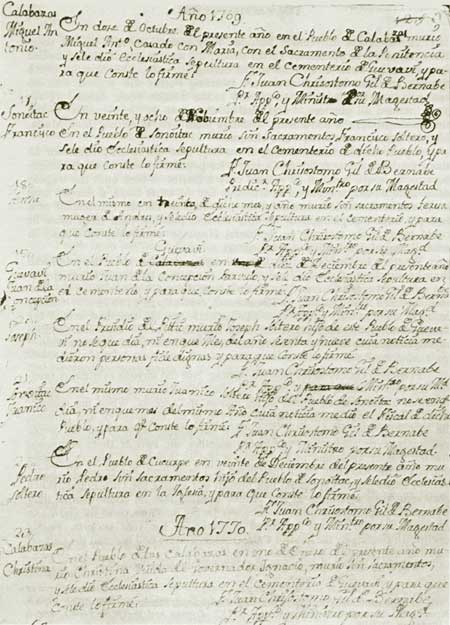

Grayrobes from the college also ministered to the people of Querétaro, primarily in the confessional, where Gil if present could be found daily. The "simple and artless" Francisco Garcés, still too young to confess women, became "the Children's Padre." [21] When the urgent call to heathen missions was sounded in the summer of 1767, both men volunteered, bided their time with the others for twenty weeks in Tepic, and the following January sailed for Guaymas on different ships. Juan Gil found himself crammed aboard the Lauretana, an ill-constructed vessel of only fifty-four tons, confiscated from the Jesuits. [22] Buffeted by furious squalls, the little ship rose and fell sickeningly. The friars threw up till their whole bodies ached. Forty days later, in early March, 1768, the Lauretana stood in at the port of Mazatlán, five hundred miles south of Guaymas. Meanwhile, the San Carlos, carrying Father President Mariano Buena y Alcalde, Garcés, and four more friars, had been blown all the way back to San Blas. Six of the Franciscans, terribly ill from their ordeal, begged the captain of the Lauretana to let them go on by land. He consented. When they were safely ashore, Father Gil admitted to the dark-skinned andaluz Fray Juan Marcelo Díaz, who had shared with him the trials of the Mercurio four years earlier, something that had been troubling him. Not long before they had set out from the college, Gil, it seemed, confessed a poor woman possessed by the Devil. She told him that the Devil had predicted his death. He had escaped on the coast of Yucatan, but in Sonora he must die. [23] If he could have studied an accurate map, Father Gil would have seen how the river later called the Santa Cruz rose in the mountains east of present day Nogales; how the watershed, like a giant horseshoe open to the south, drained into the grassy San Rafael Valley; and how from there the main stream flowed on south past mission Santa María Soamca, less than ten miles below the present international boundary. At the place known as San Lázaro the stream bent abruptly west and then northwest winding gently through a fertile valley called locally the San Luis. Some people claimed that the land in the San Luis Valley was the richest in all the province, but in 1768 its settlements—San Lázaro, Divisadero, Santa Bárbara, San Luis, Buenavista—stood crumbling and vacant for fear of the Apache. Meandering on northwest through grassy, largely unchanneled valleys, wetter and more open than today, the river passed mission Guevavi, Calabazas, Tumacácori, and the presidio of Tubac. From Tubac to mission San Xavier del Bac and Tucson it ran nearly due north then took off again north westward over a hundred miles till it joined the Río Gila just southwest of today's Phoenix. Only in a semiarid region would this meager flow be dignified as a river. In some places it stood in malarial ciénagas, or marshes, and in others north of Tubac it sank into its sandy bed and disappeared from sight completely. Yet this was the life line of the northern Pimería, of three missions and a presidio. Misión los Santos Ángeles San Gabriel y San Rafael de Guevavi was even cruder than he expected. After a year of neglect the shabby brown pueblo looked wholly unprosperous, its mud and adobe-block walls hardly rising above the surrounding mesquite, its indigent Pimas and Pápagos reduced to a few dozen. He would endure as Job the squalor, the heat and mosquitos, the sullen, indifferent neophytes, the disease and dying, and the Apache menace. Always the penitent, Fray Juan Crisóstomo Gil de Bernabé welcomed a heavier cross. His Indians would not understand, but his interpreter would call him a saint. [24] He arrived in mid-May, driest month of the year, perhaps in the company of Captain Juan Bautista de Anza who had a twenty-day leave from the southern campaign to collect provisions in the missions of Soamca, Guevavi, and San Xavier. [25] Gil, one of the early arrivals, had been provisionally assigned to Guevavi by Governor Pineda. Six weeks later he would have chunky Fray Francisco Roche, fellow castaway from the Mercurio, thirty miles southeast at Soamca and the unsophisticated Fray Francisco Garcés up the road sixty miles north at San Xavier. But for the time being the slender, zealous grayrobe was the only priest in the northern Pimería.

The principal village of his first heathen mission, the one where he would live, took up most of the clearing atop a several-acre mesilla just east of the river. Blocks of low, cluttered adobe huts housed the Indians of the pueblo proper. The modest church, oriented roughly north-south, stood at the eastern edge of the eminence, its entrance looking south on the irregular plaza. A Jesuit superior had described it in 1764 as "a very good church" but added that the sanctuary was shored up. In his opinion it could easily be repaired. Inside, Juan Gil found the church

Attached to the church and west of it was the one-story convento with all its doors facing inward on a small patio. Here Father Gil had his quarters. From Guevavi he could see brown hills, not actually as bare as they appeared, nearly all round but pressing in closest from the west. The shallow, northward-flowing river passed through a narrows at Guevavi. Giant old cottonwoods marked its course. Above the pueblo to the south the valley opened up. Here the mission Indians irrigated plots of maize. In some places on the river flats, unhealthfully close to the pueblo, the water stood in cienagas and bred mosquitos. Off to the north, down the broken, chaparral-covered valley cut by a thousand arroyos, he could see the peaks of the Sierra de Santa Rita, a hazy purple in the distance. To call on his three visitas the friar and his escort rode north downriver. The trail, described nineteen months earlier by a military engineer, kept to the river "whose banks are very grown up with cottonwoods, and the rest of the plain with many mesquites and other bushes." The closest visita, San Cayetano de Calabazas, about five miles from Guevavi, blended into a hillside east of the river and well above it. The view from the site north down the valley was impressive, Calabazas itself singularly unimpressive. The same engineer called it "a small pueblo formerly of Pimas Altos, who all perished in a severe epidemic, and repopulated with Pápagos." [27] Calabazas did not even have a church. The small adobe, reported "half built" in 1761, stood roofless. There was no cemetery. Early in 1769 when Ignacio Guíojo-muri, native governor of Calabazas, died, Fray Juan Gil would have the body carried south and buried in the church at Guevavi. Not many more than a dozen families lived at Calabazas. [28] Riding on, the party passed the mouth of Sonoita Creek, trickling into the river from the east, and by the detached and looming mountain called San Cayetano. Ten miles beyond Calabazas the Franciscan caught site of San José de Tumacácori, set back in the mesquite several hundred yards west of the river. Close behind, the dark, rocky Sierra de Tumacácori rose above tan hills forming an imposing backdrop. Here Father Gil was gratified to find both church and cemetery, and more natives than at either Guevavi or Calabazas, surely over a hundred. Like Calabazas, Tumacácori was an artificial congregation. Fifteen years before, in 1753, a garrison of frontier soldiers had preempted Tubac, only a league north on the same side of the river. They had rounded up all the Indians who had returned to this part of the valley after the uprising of 1751—families they dispossessed at Tubac, others from the pre-revolt east-bank rancheria of Tumacácori, and Pápagos—and settled them here. A Moravian Jesuit consecrated the church in 1757, a plain flat-roofed adobe building roughly sixty by twenty feet. The new pueblo's population had risen and fallen almost with the seasons as Pápagos came and went and as epidemics took their toll. But because the presidio stood so close, the Jesuits had thought of making Tumacácori a cabecera. [29] Here on May 20, 1768, in a scene that recalled the days of Father Kino, the gray-robed friar lined up and baptized nineteen Pápagos, evidently instructed beforehand. To seven of them he gave the name Isidro or Isidra in honor of the Spanish farmer saint and patron of Madrid whose feast fell earlier in the month; one he called Juan Crisóstomo [30] This was what he had left the mountaintop for, the reason he had crossed an ocean—to redeem spiritually heathen Indians, the more abject the better. But Fray Juan had come too late.

The native population of Pimería Alta was dwindling. One 1768 report put the overall decline for Guevavi and its visitas at over 80 percent, down from a peak during the Jesuit years of three hundred families to only fifty. Where six had lived now only one remained. [31] Transient Pápagos would continue to show up at planting and harvest times to work and fill their bellies in the river pueblos. Some would stay. But, as Father Gil soon learned, few of the heathens wanted to become permanent members of the mission community. In the missions people died, they said. By commission of the bishop of Durango the Jesuits of Guevavi had served as interim chaplains at Tubac. Since there was hardly ever a regular military chaplain assigned to the post, the duty in effect became permanent. In 1768 Bishop Tamarón passed it on to the friars. That gave Father Gil the chance to preach "home missions even while ministering to the heathen—for a missionary, seemingly the best of both worlds. There must have been close to five hundred persons at Tubac. Most were gente de razón, a generic term setting people culturally Hispanic but racially mixed apart from both Indians and Spaniards. In addition to the garrison of fifty-one men, including three officers and the interim chaplain, their dependents, servants, and assorted hangers-on, dozens of settlers had clustered around the presidio, many of them refugees from the abandoned ranchos upriver. A census of Tubac settlers compiled a year earlier, in the spring of 1767, showed 34 heads of family, 144 dependents, plus 26 servants and their families, for a total of well over two hundred. [32] The Sonora frontier officer corps and their families, mostly criollos born in the province, many like Juan Bautista de Anza of Basque lineage, hung together and intermarried. Along with the wealthier ranchers, miners, and merchants they were the frontier elite, the gentry. They owned the land. Anza, for example, owned or came to own frontier properties in the vicinities of Fronteras and Tubac, among them Santa Rosa de Corodéguachi, Sicurisuta, Divisadero, Santa Bárbara, Cíbuta, Sásabe, and Sópori. [33] Captain at Tubac since 1760, the vigorous thirty-one-year-old Anza had impressed even the peninsulares, those proud Spaniards born in the mother country, like Governor Pineda and Colonel Elizondo. The Marqués de Rub&ieadute;, a member of Charles III's high-ranking military mission to New Spain, had met Anza when he inspected Tubac during the Christmas season of 1766. "Because of his energy, valor, devotion, ability, and notable disinterestedness," Captain Anza was in the opinion of Rubí "a complete officer" deserving of the king's favor. As a presidial commander Anza followed in the tradition of his father, a peninsular "of singular merits," and his criollo grandfather on his mother's side. Born in the summer of 1736 at the presidio of Fronteras, a hundred miles southeast of Tubac, he was not yet four years old when his father died in an Apache ambush. As he grew he followed the prescribed course for a member of his class. He joined a garrison commanded by a relative, in his case Fronteras under his brother-in-law Gabriel Antonio de Vildósola, serving first as an unpaid teenage cadet and then moving up in rank. By the age of nineteen he had been commissioned lieutenant. An inspiring leader of men, Anza had the grit to engage in hand-to-hand combat. He had campaigned against rebel Pimas and Pápagos, against Seris, but mostly against Apaches. [34] The royal presidio of San Ignacio de Tubac was meant to keep the peace with Pimas and Pápagos and to defend the province against Apaches. If Father Gil anticipated a real frontier fortress, even a neat military enclosure or rudimentary fortifications, his first view disabused him. Low and totally constructed of adobe, it amounted to no more than a disorderly cluster of buildings with the large U-shaped casa del capitán at the center. The presidial chapel, begun at Anza's personal expense, stood just to the northwest with cemetery in front. Because the crown had invested so little in the physical plant at Tubac, and because he thought so large a concentration of settlers could defend itself, the Marqués de Rubí had recommended that the garrison be moved. [35] The pueblo of San Ignacio de Sonoita, Fray Juan Gil's third visita, lay half-hidden in the hills separating the parallel valleys of the Santa Cruz and the San Pedro. To get there he either rode east from Tubac or Tumacácori around the far side of San Cayetano Mountain or up Sonoita Creek. In either case he ran the risk of ambush. Sonoita stood directly in the path of Apaches raiding southwestward into the Santa Cruz Valley and beyond. Some of the Sobáipuris evacuated from the San Pedro Valley in 1762 had been settled here. If the military intended to hold the place, they would have to station a detachment of soldiers at Sonoita, as they had done at San Xavier del Bac. But Father Gil had already heard Anza's excuse. The captain and thirty-five Tubac regulars had been ordered south to fight Seris [36] That left the presidio with fifteen soldiers and a few dozen poor and ill-armed militiamen, hardly enough to guard the horses. Early in June five Sonoita Indians looked up from work in their fields to see an Apache war party bearing down on them. Instead of running they held their ground and fought a gallant delaying action while the women and children scrambled for the pueblo. Two of the five died. "One was a close friend of the most courageous Indian known in all the Pimería," wrote Governor Pineda,

Fray Juan Gil soon found out what the viceroy's instructions to the college meant in practical terms. The reformers had made him a guest in his own mission. When Captain Anza, provisioning his troops with wheat, maize, and beef in the missions, negotiated for Guevavi's quota, he did so not with the friar but with Comisario Andrés Grijalva. When he arranged for the pay of Guevavi Indians fighting in the southern campaign, he dealt not with the missionary but with Grijalva. Father Gil was left to record the casualties. [38] As soon as Father President Buena and the other late arrivals reached their missions, Governor Pineda ordered the comisarios to hand over the churches. Comisario Grijalva came to Guevavi for the formalities. In the presence of Fray Juan Gil, the native governor, and another Indian official, Grijalva proceeded to inventory item by item what the Jesuits had left in the church and sacristy: santos, sacred vessels, vestments, down to the last purificator for cleansing the chalice. Next they moved on to the casa del Padre in the convento. Every cup, pot, and pan, the few books, some tools, the meager furniture—everything usable and unusable was listed. When the comisario had satisfied himself that he had included it all, he asked the missionary to cosign the document. Then he rode on north to do the same for Father Francisco Garcés at San Xavier. [39] As far as the reformers were concerned, the Franciscan replacements now possessed all they needed to function spiritually as missionaries to the Pimas. How woefully wrong they were became obvious as the summer wore on. When he had been at Tubutama no more than a couple of weeks, Father President Buena confirmed his superiors' worst predictions. The new liberal way was a disaster. The king's wish that the mission Indians of Sonora not be made to work, that they be free to live and learn with non-Indians, had miscarried. "They live," wrote Buena,

Yet the Father President had cautioned Gil, Garcés, and the others to hold their tempers. For no reason were they to come down hard on their charges. Governor Pineda had made that clear. Ever since the 1751 uprising some Pimas, particularly among the so-called Piatos of the western pueblos, had refused to return to the Spanish yoke. Bands of them had joined the Seris in the wild Cerro Prieto country. On the slightest pretext, the governor believed, many more mission Indians would flock to the rebels' camps. They must not discipline the Indians, said the reformers. But that was not all. To meet mission expenses the government had consented to continue the annual subsidy, which during the last Jesuit years had amounted to 360 pesos per mission. That may have been enough for the wealthy, business-oriented Jesuits, but how, the Father President wanted to know, could a poor Franciscan maintain himself; pay a cook, houseboy, and tortilla maker; provide wine and wax for divine services; improve the mission; and offer the Indians material benefits, all on 360 pesos? After all, he pointed out, the Indians "only submit to and obey someone who gives them something, not someone who only preaches the Gospel." Governor Pineda, named by Buena the friars' business agent in Sonora, had suggested several ways of easing their economic plight. He would assign each friar some mission land to cultivate and would sell him livestock cheap, or he would immediately advance each of them one hundred pesos against their sínodos. The Father President had refused politely, saying that in such matters he had to have the approval of the college. That seemed the wisest course, since Visitor General José de Gálvez was due in August or September to review the entire situation in Sonora. Buena begged his superiors to let him know promptly by the weekly mail through Guadalajara what they wanted him to request of the Visitor General. He also asked them to consider two other perplexing problems: the supplying at a reasonable price of "clothing, footwear, chocolate, snuff, and the other things a religious cannot do without," and the crying need for two friars at each of the widely scattered Sonora missions. In the meantime he would ask the missionaries themselves to report directly to the college. [40] The protest was resounding. Their charges they described as crude, lazy, shameless, irresponsible, ill-disciplined Christians-in-name-only—docile and not beyond help, some added. The physical plants they found miserable, full of bats, and in many cases threatening ruin. To get from one mission village to the next they ran the risk of mutilation and death at the hands of the Apaches. One friar per mission simply could not cope with the many needs of such scattered flocks. The annual stipend, they predicted, would scarcely cover church expenses, let alone maintain a missionary, clothe the Indians, feed the hungry and the sick, and attract the heathen. Supplies if available at all cost a fortune. But worst of all—they were not even masters in their own missions. So long as they had no material means to awaken their neophytes' interest, and fill their bellies, no authority to mete out discipline; so long as they had to borrow seed from a comisario and stand by while Spaniards took advantage of mission Indians; so long as these conditions prevailed, the missions would remain abysmally wretched. [41] Despite the glum consensus, only a few wished to disavow their commitment. From Pimería Baja came the loudest cries. At Opodepe thin, small mouthed Fray Antonio Canals was livid. Not only were most of his neophytes half-breeds who refused to obey him, but they and their ancestors had been nominal Christians for a century and a half. By rights they should have been turned over to the secular clergy long ago. Furthermore, Fray Antonio had to spend a great deal of time in the kitchen, to supervise the dish washing, to prevent theft, and "to see that they wash the meat and remove the worms and moths; otherwise all would arrive scrambled on the plate." While the superiors decided what to do with "these curacies," Canals prayed for God's help "to get me out of this Purgatory, not to say Hell." [42] If they stayed in Pimería Baja, some of them feared, they like the Jesuits would be dragged into bitter civil-ecclesiastical clashes. [43] And from Ures pock-marked Esteban de Salazar lamented, "My job here is not apostolic missionary but glorified innkeeper," not misionero but mesonero! [44] At least in Pimería Alta they were closer to the heathen. Up the road from Guevavi at San Xavier and Tucson, Father Garcés rejoiced that he had no Spaniards in his care. "I am very content," he wrote. "There are plenty of Indians. I like them and they like me." He did like them, and he seemed to understand them. He knew full well that they only tolerated him at first because they knew that he could not force them to work as the Jesuit Fathers had. Yet for their own good, to protect them and provide for their needs, Garcés urged that the missionary's authority be restored. "Already we have seen the harm done in this kingdom," he had written to Governor Pineda, "because these people do not know the submission they owe their king, for even when they do venerate their priests and are subject, they are little short of heathens. If this is lost they will be worse." [45] At Santa María Soamca, not at all content, Father Roche admitted to his superiors that "speaking for myself I would rather live on chili and tortillas and work in a sweatshop than continue with things as they are now." [46] Governor Pineda said he wanted to help: if the missionaries would make known to him their needs he would try to supply them, evidently on account from his own store. At Soamca, Roche needed a tablecloth, napkins, and some cups and saucers. At San Xavier, Garcés needed locks and a chest to keep his vestments and sacred vessels free of vermin, another lock for his chocolate, a small box for the oils, some molds for hosts, a large kettle, an awning, a pocket inkwell for the trail, a razor case, and other such items. Reyes wanted beans to plant. [47] To provide themselves with the simple necessities, some of the friars had already bought on credit more than their first year's stipend would cover. Most believed that even five or six hundred pesos annually would not be enough unless they were given recourse to mission produce. Father Salazar of Ures commented on the buying power of the peso in Sonora. At Pineda's store he had spent 9-1/2 pesos for a half ream of paper suitable for recording baptisms, marriages, and burials at his mission, 2 pesos for two ounces of saffron, 3 pesos for two ounces of cloves, and 4 pesos for two ounces of cinnamon. Half a pound of pepper, a pair of shoes, a pair of stockings, and three varas (a vara measures about 33 inches) of Mexican baize for a skirt to cover a big Indian girl who was running around naked pushed his bill to 29 pesos, which the friar settled by saying twenty-nine Masses for the governor. He also had to buy salt, a tercio at 4 pesos. He refused to pay the 12 pesos Pineda was asking for a beef cow. Instead he bought seven on the hoof at 2-1/2 pesos each. But because the hostiles had stolen all the mission's horses he had no way to round them up, and so he was eating mutton. An arroba (25.36 pounds) of wax for candles to burn on the altar had cost him 21 pesos 7 reales at the mining town of San Antonio, seventy-five miles southeast of Ures. Wine sold that year at 1-1/2 pesos per cuartillo (.12 gallon). Butter and lard were so scarce that he was doing without. By shopping around he had bought 176 bars of soap for 11 pesos, or sixteen bars for a peso. Pineda was selling only a dozen for the same price. Salazar explained the quantity. Not only did he use soap to keep himself clean in his filthy surroundings, but also to trade to his Indians for eggs on fast days. [48] The friars wanted to control the missions of Pimería Alta as the Jesuits had, but they could not say so, not in 1768, not while the reformers still claimed credit for emancipating the Indians from Jesuit slavery. So they hedged. They pointed instead to the success of the college's missions in Texas and Coahuila. There the friars, two at each mission, managed the temporalities. There they disciplined their charges and oversaw dealings between Indian and Spaniard. There Indians worked for the missionaries and attended catechism and services. [49] Despite the burden it implied, the Franciscans in Sonora knew that they must have control over their missions' food supply. As one of the Jesuits had put it three decades earlier, "Indians do not come to Christian service when they do not see the maize pot boiling." [50] Some of the Franciscans compared Pimería Alta to Babylon. No matter how loudly they wailed they knew that things would get no better until God sent them a Cyrus. For a return to the proven way, "for the redemption of our tribulations and wants," they looked to one man, the archreformer José de Gálvez. His coming, Father Buena admitted, "we await like that of the Messiah." [51] At Guevavi the penitential Fray Juan Gil made do. He hired an interpreter and began teaching the Pimas and Pápagos of his mission pueblos to pray by rote in Spanish. Still, they seemed strangely distant. He never got to know the Indians the way Francisco Garcés did. As their spiritual father Gil felt an abiding compassion for these poor ignorant creatures. But while he was mortifying his flesh to atone for his own shortcomings—he wore a hair shirt and scourged himself—Garcés was sitting cross-legged on the ground, eating Indian cooking and learning Piman. Garcés wanted no part of "Spaniards": to Gil they were a blessing. He felt at ease at Tubac. Though the several hundred persons in and around the post, soldiers, dependents, and settlers, represented numerous racial mixtures, culturally they were Spaniards. They understood him. For Fray Juan it was back to the revival trail. "The presidio was becoming a spiritual wasteland," wrote another friar, "but the Father implored so much, preached so much, that even the deepest-rooted vices were wrested out." Father Gil put Mass on a set schedule, and instituted various devotions. [52] Certainly his impassioned preaching was a diversion from the monotonous rounds of a frontier post. The wives and mothers of the community welcomed the friar's influence. The troopers grimaced when he stopped the girls from provocatively splitting their skirts to show their petticoats. [53] While Fray Juan Gil was combating sins among Spaniards in Tubac that first summer, Garcés accepted an invitation from heathens. With no more baggage than the horse he rode, a little jerky and pinole, and a pot of sugar for the children, the trusting young minister of San Xavier, in his words,

From near the Gila Garcés wrote to Father Buena and sent the letter by a Pápago. Although the Father President admitted that had he known what Garcés was up to he would have forbidden the dangerous solo entrada, he now saw it as divinely inspired. At last he had something favorable to report to the college. These heathens had welcomed Garcés. They had begged for baptism. "They were much impressed," Buena exulted,

For Francisco Garcés this was only the beginning. The Franciscans had their Kino, and, they were quick to point out, he traveled without soldiers and was prudent with the baptismal shell. Father Gil learned of his paisano's success with the heathens firsthand, though not under the circumstances he might have wished. Soon after his return Francisco Garcés fell dreadfully ill. Struck speechless for twenty-four hours, then racked by prolonged chills, he lay utterly helpless. Gil had him carried the sixty miles south to Guevavi. There the missionary of San Xavier recovered, and the two friars talked. Meanwhile, death stalked San Xavier. [55] While the friars waited in vain for Gálvez, and while they prayed at Governor Pineda's request for victory over the Seris, the Apaches ran wild. By the mid-eighteenth century the Apache problem had come to overshadow all others on the Sonora frontier. Once they had acquired the horse, the loosely organized, seminomadic bands of Chiricahua and Western Apaches evolved a way of life dependent to a large degree on raiding and warfare. [56] Any time, but especially from fall, when harvests were in, through the cold season of winter and into the spring, raiding or war parties, ranging from a dozen men or fewer to a couple of hundred, left the mountains north and south of the Gila and made for the frontier settlements. [57] Those they raided—missionaries, farmers and ranchers, presidial soldiers, miners, Spaniards and Indians alike—learned to live with a constant state of intermittent warfare, or they fled. That fall of 1768, the new missionaries found out how vulnerable their missions were. First, on September 5, an Apache war party estimated at two hundred drove off the Terrenate garrison's entire herd of remounts, leaving one soldier dead, two wounded, and the rest with only the animals they had under them. Riding the stolen Terrenate horses, the hostiles next hit San Xavier. Garcés was still at Guevavi. "It was the providence of God to prevent the Apaches from carrying him off live or killing him." Governor Pineda described for the Viceroy Marqués de Croix what happened. Between eight and nine in the morning on October 2, someone yelled that Apaches were rounding up San Xavier's horses and cattle. The two soldiers from Tubac living in the mission as a guard shouted to the native governor to roust out some men and follow. In hot pursuit they overtook part of the cattle. They wanted the mares too. Gaining on the Apaches as they approached the "Puerto de la Cebadilla," present Redington Pass, the pursuers spurred ahead, right into an ambush. The governor of San Xavier died, and the hostiles carried off the two soldiers. Next day Apaches struck seventy-five miles southeast stealing 37 oxen and 180 head of cattle from Santa María Soamca. The few mission Indians, remembering all too well a recent Apache attack in which ten of their number died and three were abducted, let them go. The ensign at Tubac, acting post commander in Anza's absence, led the punitive patrol but found no one to punish. [58] The most frightful attack that season, the one everyone remembered for years afterward, occurred in November at Soamca. The pueblo never recovered. Fray Francisco Roche, coldly received by the Pimas of Soamca in June because of his poverty, had stuck it out there a month and a half then moved to his visita, Santiago de Cocóspera, some twenty miles south. He had been warned about Soamca. It was, Father President Buena had heard, a most unhealthful place and extremely exposed to Apache attack. [59] But for some reason, on Saturday, November 19, 1768, Roche was back. That morning about seven, a host of Apaches rode down on Soamca bent not on merely running off what little stock remained, but on utter destruction. "Now on horseback, now on foot," they took over. They set fire to the Indians' dwellings, the storerooms, and Roche's quarters.

The thirteen mission families, besieged in one room all day, fought for their lives "with lances, arrows, and guns." "I was in my room alone for something like three hours," recalled Father Roche.

But the Apaches spared him. About five in the afternoon they withdrew leaving five Pimas wounded—a remarkably light casualty count considering—and Father Roche with no more than the habit on his back. Mission Santa María Soamca was a smouldering shambles. [61] This sustained ten-hour siege by Apaches and their earlier raids in force on the Terrenate horse herd seemed to be acts of war, of retaliation for hostilities committed by Spaniards and Pimas against them. It was a vicious circle. The attackers' discipline; their alleged use of cueras, the multi-layered, sleeveless leather coats worn by the presidials; and their exchanges with Roche in Spanish suggest an indio ladino, a native leader or adviser familiar with the ways of Spaniards, perhaps a vengeful non-Apache. News of the Soamca disaster reached Governor Pineda just as he heaved his bulk onto a horse to join Colonel Elizondo in the first concerted invasion of the Seri-invested Cerro Prieto. All the governor could do was order the ensign of Tubac into the field again with twenty-six presidials and fifty Pima auxiliaries. This time his trackers succeeded, too well. Apaches were everywhere. Wheeling his column around, the acting presidio commander led a retreat back to Tubac while the hostiles harassed the rear guard. He reported two of the enemy lanced to death and others wounded. [62] On February 17, 1769, about noon a brazen party of Apaches struck at Tumacácori, almost under the nose of the Tubac garrison. They would have got away with all the stock "had not some soldiers with the help of the natives of the village stood up to them." [63] Three days later, again in broad daylight, about thirty Apaches assaulted San Xavier. While most of the attackers kept Father Garcés and the mission guard pinned down in the center of the village with a hail of arrows, others got off with most of the livestock. Before they withdrew "they shot many arrows at the door of the church." After another raid March 3, Comisario Andrés Grijalva reported the mission reduced to only forty cattle and seven horses. On the eleventh the Apaches returned to deserted Soamca. They sacked the room where a few furnishings and old tools had been stored and they finished burning the convento. It was as if they were defying the people of Soamca ever to come back. Later in March Garcés joined the ensign, ten Tubac soldiers, fifteen settlers, and forty Pima auxiliaries on a sally north down the San Pedro Valley almost to the Gila. They came upon the Apaches camped in a rugged area. Because they were outnumbered, because the auxiliaries were mostly untried boys and the settlers lacked mettle, once again the ensign ordered retreat. [64] The harassed friars knew well enough that Governor Pineda and Colonel Elizondo planned first to destroy the Seris and their Piato allies, then to march the full expeditionary force against the Apaches. They listened while interpreters informed the mission Indians of the governor's proclamation putting a bounty on Seris and Piatos:

Francisco Garcés wondered if the governor could dispose of the rebels in time. Later in the spring of 1769 escaped captives reported a massive gathering of hostiles bent on the total destruction of San Xavier del Bac. On June 14 twelve Apaches rode by Sonoita, crossed the Santa Cruz, and disappeared to the west. Twice as many soldiers and Pimas gave chase. Near Arivaca, until the revolt of 1751 a visita of Guevavi, the raiders ambushed five of their pursuers. A few days later they rode off with a big herd of Guevavi cattle. If a dozen could do that, asked Garcés, what would the rumored horde do? "As things now stand, what will become of Cocóspera, Guevavi, and this mission? I say that what happened to Santa María [Soamca] will happen to them, unless there are miracles!" [66] The man they all expected miracles from, Visitor General José de Gálvez, was coming at last. For eight months the king's brilliant, megalomaniacal minister extraordinary had been in Baja California trying to squeeze pesos out of the desert. If he had failed to make the peninsula economically productive, which he never would admit, he had succeeded in launching Father Serra and the so-called Sacred Expedition to occupy Alta California. He then turned his attention to Sonora. First he must bring the war against the Seris and their allies, Sonora's internal cancer, to a rapid and glorious conclusion. Writing to Father President Buena from La Paz, Gálvez asked the friar to undertake a dangerous secret mission, to confront the Seris with the prospect of pardon, without disclosing that the initiative had come from him. If the hostiles would lay down their arms upon the visitor general's arrival their past crimes would be forgotten. On April 19, 1769, Buena vowed to try. He moved south to Ures, close to where the action was, and displaced Father Salazar to Tubutama. Although he failed in his peace mission, and nearly lost Father Juan Sarobe in the effort, the Father President did ingratiate himself with the all-powerful Gálvez. [67] The ship carrying the visitor general put in far down the coast. After proclaiming a general amnesty for all the rebel Indians who would surrender within forty days, the king's minister proceeded inland to the mining town of Alamos. Three weeks later Father Buena arrived. The friar came right to the point. He had compiled a statement setting forth in detail the sad state of the missions and condemning the new system. [68] It simply was not practical. If the friars had neither the material means nor the authority to congregate their neophytes and keep them congregated, they had not a hope of saving their souls. Lazy, short-sighted, insensitive, and unskilled, these Indians, Buena asserted, were not ready for civil rights. Besides, with the mission population roaming about at will, the frontier lay all the more exposed. The visitor had read of the depredations. Any system that weakened the missions weakened the province. That kind of hard reasoning the visitor general understood. On June 3, 1769, presumably with Father Buena looking on, Gálvez struck down the rule of the comisarios in Pimería Alta, just as he had done in Baja California, and in southern Sonora. What was left of the mission temporalities he ordered surrendered immediately to the friars. He made it clear though that the measure was temporary, pending further investigation. [69] Two weeks later the visitor general wrote in no uncertain terms to Governor Pineda. The mission temporalities must not be thought of as confiscated goods. They had not belonged to the Jesuits, who only administered them and "profited unjustly." Rather they belonged to the Indians. Pineda had better have the books straight for every mission, plus a record of the gold and silver taken from each and a listing of supplies furnished the friars. The visitor would soon be calling on him. [70] In the missions of Pimería Alta a retreat from the Enlightenment had begun. Moreover, the archreformer himself had decreed it. Enlightenment proclaimings were not enough. Without a much larger investment than the government was prepared to make, without more vigorous action, it was hard to see how any fundamental mission reform could succeed. The Jesuits would have smiled. The semi-literate Andrés Grijalva was no businessman. In October, 1768, Governor Pineda had asked the comisarios for an itemized financial statement for each Pimería Alta mission. It was to show the original inventory at the time of the Jesuit expulsion and what remained fifteen months later. The other comisarios accounted scrupulously, if not always honestly, for every disposition—on account to the friar, distributed among the mission Indians, sold, stolen, or rotted. They listed the church furnishings and noted that all these had gone to the new missionaries. They accounted separately for each visita. Not Grijalva. He merely made two simple lists, omitting any mention of the church furnishings, and only cursorily explaining the substantial decrease. The receipts he held from Father Gil, Captain Anza, and others, he believed would cover him. The Guevavi comisario listed a varied stock of textiles (13 varas sack cloth, 62 varas baize, 19-3/4 varas Rouen, 2 bolts wide Brittany, 9-1/2 ounces silk twist); some items of clothing (2 cambric and choice linen handkerchiefs, 4 doz. gilt buttons, 1 pr. tooled half-boots, 1 pr. linen stockings, 4 ordinary hats, 11 prs. shoes); various odds and ends (1 old snuffbox); tools for farming, saddlery, carpentry, and smithing; and some weapons (12 lance shafts with sockets, 10 lbs. powder, 1 old rapier, 1 large machete, 1 musket with case, 1 leather horse breastplate with rump cover). A count of the mission's livestock showed nominal increases in some categories. The horse herd was down markedly:

Some expenditures Grijalva explained: 59 pesos in goods to Manuel Barragán of Tubac who served as helper; 74 pesos in saddle blankets and sackcloth to the muleteers; 36 fanegas of maize and 25 sheep to Captain Anza; 11 marks 5 ounces of crude silver, 13 pesos 3 reales in gold, and 21 pesos 7 reales of coined silver in the care of Captain Bernardo de Urrea; 50 cargas of wheat shipped to the headquarters of the Seri campaign; 75 fanegas of pinole made by the muleteers and 8 bulls used in carting; 100 sheep to Captain Francisco Elías Gonzáles of Terrenate; and 60 fanegas of pinole made for the auxiliaries at Anza's command. As proceeds on hand from the sale of mission goods the comisario reported 34 marks in silver. Everything Grijalva had previously turned over to Gil de Bernabé—the contents of church, house, and sacristy, plus provisions—he simply entered as "goods and effects I supplied to the Reverend Father Missionary, as are recorded on his statement." Without Gil's statement one can only surmise what items from the 1767 inventory fell to the friar: surely the desk, tables, chairs, canvas cot, wash basin, the 250 bars of soap, the 40 books, the sundial, and the guitar. [71] The rest of what remained, from meat hooks to gold galloon, Grijalva surrendered to Gil in the summer of 1769. [72] With the key to the larder in the sleeve of his habit Fray Juan was now in a position to bargain with his neophytes. Though he still lacked the authority his Jesuit predecessors had enjoyed, as custodian of the maize, beans, wheat, and livestock grown on Guevavi's common fields he, not the comisario, was the Indians' keeper. The more industrious of his wards could still plant a milpa on their own, just as they had in the days of the Jesuits. They could still trade a fanega of maize worth twelve reales for a bar of soap worth a half-real. But now whenever they were hungry they came to the Padre; they accepted a dole from the common granary; and with full bellies they learned again to pray the rosary. For the friars themselves, management of the temporalities caused considerable personal anguish. Reconciling the acquisitiveness of a businessman with the Franciscan vow of poverty put a strain on their consciences. But there was no other way. To keep from actually handling cash the missionary had it locked in a strongbox which he kept in his quarters. The key he entrusted to the native governor or to a gente de razón foreman whom he told when to make deposits and withdrawals. [73] For the good of souls, Fray Juan Gil a year after his arrival was well on the way to becoming master of Guevavi in the tradition of the Jesuits. Father President Buena meanwhile pressed his luck. Gálvez could do much more for the missions. In September, 1769, the stern, domineering visitor general finally left Álamos on a litter. An Indian revolt on the Río Fuerte and illness, a combination of tertian fever and melancholy, had thrown him behind schedule. His offer of amnesty had brought only a few dozen starving Seris down from the Cerro Prieto. Now he would humble the rest by the sword. On the way to campaign headquarters at Pitic, present-day Hermosillo, the visitor general, already showing signs of mental derangement, stopped over at Ures. When Father Buena and his secretary Fray Joseph del Río reiterated some of the missionaries' continuing problems, they found the archreformer receptive. He professed the highest regard for the Queretaran friars. Earlier the college had applied to the viceroy to have the 360-peso sínodo for each mission paid in lump sum from the treasury in Mexico City. That way its agent could take advantage of the lower prices, quantity rates, and better selection of the capital and ship the supplies to the missions in bulk loads at considerable savings. Gálvez wholeheartedly endorsed the plan, praising the Queretarans' economic management and pointing out in a letter to the viceroy that the friars did not "have recourse to the profits and commerce that enriched their predecessors." [74] As for the missionaries' complaint that the Indians and gente de razón showed them little respect, Gálvez would take care of that too. On September 29, feast of the patron at San Miguel de los Ures, he harangued a large crowd on their obligations and responsibilities to the friars. To put teeth in his words he dictated a set of orders. First, all Indians, chicos a grandes, must attend Christian instruction daily. For transgressors Gálvez had a remedy—twenty-five lashes for the first offense and fifty for the second. The same punishment applied to any Indian who lazed about when he was supposed to be at work. Gente de razón living in a mission should recognize the missionary as their proper priest. They need not apply to the parish priest to be married or for any other reason, and they owed him nothing in fees. From the beginning the friars had complained of meddling by the secular clergy, who, they alleged, did not venture forth to serve the gente de razón, but only sent agents to collect from them. Mission Indians, Gálvez further ordered, must stop thinking of themselves as relatives of heathens, but rather as hijos de la misión. He urged the use of Spanish whenever possible and the teaching of that language to all Indian children. Finally, he dictated that mission Indians give up their heathen surnames and adopt those of Spaniards. Although these on-the-spot orders of the visitor general lacked the weight of formal decrees, they gave the friars a temporary means of restoring their authority in the missions. Next day Father del Río dispatched copies to the other missionaries in the field. [75] When Gálvez suggested that the humbled Seris would need a mission, Father Buena willingly consented to accompany him on to headquarters. At Pitic, unexpectedly, the king's visitor fell almost literally into the arms of the Father President. Gálvez had been driving himself relentlessly. Doubts about the success of his grand design for the northwest had begun to haunt him. He simply could not anticipate every problem, see to every detail, and keep on cutting costs. After two weeks of strategy sessions with Pineda and Elizondo at Pitic, the visitor suddenly went berserk. At two in the morning of October 14 José de Gálvez jumped up out of bed to announce that Saint Francis of Assisi had appeared to him promising him a smashing victory over the Seris. Raving, he headed immediately for the barracks where he caused a near riot, yelling, shaking the soldiers' hands, and promising them fabulous bonuses. The fat Governor Pineda, rousted out by the commotion, shouted at the visitor's distraught staff to get him back to his quarters, which they did. There, over the next three days, Gálvez' personal physician bled him five times. The officers, convinced that what they had seen and heard resulted from something more serious than high fever, diagnosed the visitor general's malady as megalomania. At the suggestion of Father Buena they moved the patient to Ures. For the next five months the Franciscan Father President attended the most powerful man in New Spain as priest, protector, and analyst. He suffered with him through one stretch of forty days during which the visitor was completely out of his mind. The friar censored Gálvez' mail, deciding which reports he should see and which might upset him. When he chose to withhold news of the troops' inglorious failure against the Seris, he assured Governor Pineda that he would inform the visitor general at the first opportunity, "using what little prudence I possess to sweeten for him this bitter pill." [76] When Gálvez was coherent, when his fever abated, the Franciscan superior spoke of the need for two missionaries at each mission. He showed his patient the letters of Fray Francisco Garcés describing new dominions and thousands of beckoning heathens. For a moment Gálvez' pulse quickened and he vowed that he would go to the Gila himself, if only his health were better. [77] When at last they decided to move the visitor general, Father Buena accompanied him as far as Chihuahua. The following summer the friar heard from his friend in Mexico City, apparently fully recovered. "I have not forgotten your recommendations," Gálvez assured him. As a token of his appreciation he was sending by special delivery a number of jugs of oil for the altar lamp at Ures. [78] While some of those who had seen the visitor general at his worst languished in jail as a warning that the matter be forgotten, Gálvez began a propaganda campaign to promote Sonora as a land of opportunity. According to him, peace was at hand: better days lay ahead. In Pimería Alta things got worse. The year 1770 nearly proved fatal. The March epidemic which decimated the embattled Seris evidently spread north. In one week Juan Gil at Guevavi buried eight mission Indians, including Governor Eusebio of Tumacácori. Apaches killed seven from Calabazas at one blow. [79] To the west Pápagos disguised as Apaches began stealing and slaughtering stock. Several of the friars feared an uprising. The specter of the whole Pápago nation—estimated at more than three thousand—joining Seris, rebel Pimas, and Apaches threw a scare into the grossly overweight Governor Pineda, who lay in bed at Horcasitas partially paralyzed by a stroke. At once he ordered Captain Anza and sixty presidials detached from the southern offensive. They were to join Captain Bernardo de Urrea of Altar for a march in force through the Papagueria "to extinguish the uprising, punish the guilty, and assure those not involved of the good faith with which they will be treated." [80] The strategy worked. The Pápagos again professed their loyalty. Fresh from his peace-keeping swing through the desert, Anza called on Father Garcés at San Xavier. After an argument over whether or not the mission should provide free rations to the Tubac soldiers Anza assigned to guard it, the friar and the captain reviewed the crisis at hand. The people of Tucson, mostly Sobáipuri refugees from the San Pedro Valley, had threatened to abandon the place. For over a year Garcés had been urging that a resident missionary be sent to Tucson. Both men recognized the strategic importance of this "gateway to the Gila." The Indians could have cared less. Fed up with increasing Apache raids and the lack of assistance from the Spaniards, they had resolved to move north to the Gila. Anza would dissuade them. At Tucson the captain called the headmen together and listened to their complaints. Then he showed them where they could build a large earthwork corral-fortification with embrasures. He did everything he could to convince them that it was in their best interest to remain at Tucson. They would, on one condition: that a church be built for them like the ones in all the other pueblos. They claimed that the missionaries had never supplied them with provisions so that they could build a church. When Garcés promised them enough wheat, they agreed to stay and build. [81] Before he reported back to Governor Pineda, Anza struck at some Apaches, and they struck back. In a fourteen-day chase the captain's force killed two men and two women carrying bows and arrows in the guise of men. They captured seven Apache children. [82] But no sooner had the redoubtable officer withdrawn from the field when Apaches devastated Father Gil's visita of Sonoita, seemingly in retaliation. It was the bloodiest assault in the mission's history. The attackers surrounded Sonoita. They plainly intended to kill some Pimas, allies of the Spaniards. Terror-struck, the women and children crowded into the house where Fray Juan stayed during his visits. The Apaches broke through and slaughtered nineteen. A sweating Father Gil arrived with an escort to bury the dead. His terse entry in the mission book, dated July 13, 1770, named all nineteen, "who died at the hands of the Apaches . . . and therefore without the sacraments." Among them were Governor Juan María, his wife Isabel, and eleven Pima children. [83] Father Gil had been thinking of moving. Like his Jesuit predecessor he recognized the vulnerability of Guevavi. Its population was down. Its neighbors to the south had fled. It seemed only a matter of time until the tragedy of Soamca would be repeated at Guevavi. On the other hand, a musket fired at Tumacácori could be heard by the presidials at Tubac. Tumacácori now had the largest population of his four mission pueblos. And from there he could more easily minister to the sinful Hispanic community of Tubac. It seemed logical that he live at Tumacácori. Whether he decided to pack up abruptly, perhaps after the homicidal Apache attacks on Calabazas and Sonoita, or whether he simply began spending more and more time at Tumacácori, Fray Juan Gil did transfer the mission cabecera from Guevavi to Tumacácori, evidently in 1770 or 1771. Early in 1773 his successor referred to Guevavi, the pueblo that had served the Jesuits continuously for forty years, as the antigua cabecera: only nine families remained. For the next half-century and more the friars lived at Tumacácori. [84] Francisco Garcés never enjoyed writing. Nor did anyone ever enjoy reading his messy scrawl. As a result he often prevailed upon his Franciscan brethren to make clean copies of his diaries and reports. When the minister of San Xavier rode south in the fall of 1770 to see his neighbor and paisano, he had with him a bunch of incredibly unreadable notes. Juan Gil wrote painlessly, even elegantly. Presumably together the two of them composed for the Father Guardian in Querétaro a legible account of Garcés' second entrada to the Río Gila, which they dated at Tumacácori, November 23, 1770. A lethal measles epidemic had broken out among the Gila Pimas. When they sent word to Garcés at San Xavier begging that he come baptize their dying children, he responded at once. As far as he knew, José de Gálvez in Mexico City had already approved missions for the Gila peoples. Riding northwest, passing by the ancient Casa Grande, Garcés had reached the Gila on October 20. When he had baptized the sick children—most of whom, he learned later, died—and preached in the Pima rancherías, he resolved to go on downstream to the Yuman-speaking Opas. Overcoming the objections of the Gileños, who wanted him to stay with them, and leaving behind his four fearful San Xavier Indians, he took one horse and a Gila Pima guide and rode on.

The Opas he found friendly, curious, and somewhat cruder than the Pimas. They wanted to know what was under his habit, if he were man or woman, if he were married, and other things "consistent with their rudeness." Yet "it broke my heart," he admitted, "to leave those people, for some of them are dying of measles. I only baptized one child already expiring whom I found by the sound of its crying." His sympathetic description of the Indians on the middle Gila shows Garcés at his best as a pioneer eighteenth-century ethnologist.

After he had received a naked Cocomaricopa delegation from the Río Colorado, and told them he would visit them another day, Garcés headed back across the stark northern Papaguería to San Xavier, which he reached, in his words, "much improved in body for the exercise." In all he had traveled nearly two hunrded and fifty miles. [85] Father Gil had been sick before, but this time it was frightening. "Because of his great labor and little concern for his own comfort and health" he found himself in the spring of 1771 utterly incapacitated, his hands and feet paralyzed. There was nothing to do but let them carry him south one hundred and fifty miles to the hot baths near Aconchi in the Sonora Valley. A sick Jesuit, who had labeled the mission "baneful Guevavi," described a similar experience thirty-seven years earlier. Each time the party encountered rough going Spaniards would take the litter "so that the incautious though painstaking Pimas would not let me roll down into a gorge." [86] While Gil took the cure in the south Father President Buena dispatched an untried interim replacement. Twenty-eight years old, of medium height, swarthy, with a mole over his left eyebrow, Fray Francisco Sánchez Zúñiga rode into Tumacácori ahead of the summer rains. [87] A country boy from northern Extremadura, he had crossed the Atlantic with thirty-seven other recruits in 1769. After no more than a few months at the college he and some of the others had set out for Sonora to reinforce the overworked friars in the field. Tumacácori opened the new missionary's eyes. [88] That summer in the salons of Mexico City they were reading a Galvez-inspired tract entitled "Concise news of the Military Expedition to Sonora and Sinaloa, its favorable conclusion, and the advantageous state in which both provinces have been put as a result." At Tumacácori the shaken young friar read two burial entries he had just written—for five mission Indians killed by Apaches. [89] Originally Colonel Elizondo and his regulars were to have vanquished the Seris and then marched north to rout the Apaches. Instead, they had been recalled. The viceroy feared a British invasion. Though Gálvez continued to predict the early triumph of Spanish arms over the irreconcilable Apaches—and to promote a Sonora stock company—Father Zúñiga heard no such bluster from Juan Bautista de Anza, who had been fighting them for twenty of his thirty-five years. Toward the end of June the Tubac commandant wrote to interim Governor Pedro Corbalán, a Gálvez appointee who had taken over from the failing Pineda. He asked for authority to recruit Indian auxiliaries from the missions of San Ignacio and Sáric on a voluntary basis. At the same time he appealed to Father President Buena to supply provisions and animals from the missions. Virtually nothing was available in the Tubac area. Corbalán approved. Buena did not answer. [90] Despite the humidity and the swollen arroyos Anza rode out of Tubac at the head of thirty-four presidials and fifty Pima auxiliaries. It was their turn to strike. After a week's march northeast, the column approached the Gila near the Sierra Florida. On August 9 they surprised an Apache ranchería. They killed nine, took eight prisoners, and wounded others. The enemy scattered, leaving behind weapons, horses, gear, and a Spanish captive. In the fray veteran Lieutenant Juan María de Oliva, a gallant, reliable, and illiterate fifty-six-year-old officer, received yet another wound. At Tumacácori, Francisco Sánchez Zúñiga buried more mission Indians. Another epidemic. [91] By mid-September Father Gil was back. Sánchez Zúñiga departed, soon to relieve unhappy old Diego Martín Garcia at San Ignacio [92] By mid-October Gil was so ill again that chunky Fray Juan Joseph Agorreta rode over from Sáric to look after him. When Agorreta's hemorrhoids flared up and he began suffering chills and fever, Francisco Garcés had to come to the aid of both. Garcés, normally a man of few words, was full of his latest entrada. He had just returned from the Río Colorado and his first experience with the Yumas. After two months alone among the heathens he had emerged at Tubutama, in the words of Father Salazar, "sound, fat, merry, and well content, dressed in the very same clothes he took from his mission, missing not a thread, except for the cord, and that not because the Indians stole it from him, but because one night when he was alone he tied his horse with or to it. The horse with a jerk broke it in three places." Garcés was just sitting down at Tubutama with Salazar to work over the diary he had kept "only in note form and this in such miserable hand that the Father himself could hardly read it," when a rider brought news of the other friars' illness. At Tumacácori he nursed them until they recovered. [93] That winter of 1771-1772, while Father Gil lamented the deaths "in the field like beasts" of three Pápago deserters from Tumacácori; while Captain Anza and the commanders of Terrenate and Fronteras struggled to launch a joint campaign against the Apaches; and while Father Garcés made it known where he felt the frontier presidios should be placed, Father President Buena took to his bed. His hemorrhoids were excruciating. No longer could he ride a horse. After four strenuous years in office, Buena had more than earned his retirement to the college. As his successor, he recommended Fray Juan Gil of Tumacácori. [94] The office of Father President demanded at once the tough-mindedness of an administrator and the understanding of a confessor. As superior in the field, he oversaw the missionaries' temporal as well as spiritual affairs. He dealt with the governor in their behalf, he supervised the distribution of supplies sent in bulk to the missions, and he passed on by circular letter the dictates of the guardian and discretory. He encouraged the missionaries and listened to their grievances. He acted as judge in cases of conflict and reprimanded any friar whose conduct he found unseemly. He could also move or remove a friar. [95] When the warrant from the college reached him, Gil accepted. Soon after March 7, 1772, when he buried Teresa, wife of Pablo, in the cemetery at Tumacácori—one year to the day before his own violent death—the lean and ascetic friar rode south for the last time along the trail by the river. [96] A new viceroy, the able and energetic sevillano don Antonio María Bucareli y Ursúa, had taken over from the Marqués de Croix in September, 1771. Though his instructions bound him to carry on in the spirit of Croix and Gálvez, he moved cautiously at first. Reports from the north were grossly conflicting. On the one hand partisans of the previous administration dwelled on the pacification of the Seris, a touted gold strike at Cieneguilla, and the exciting prospects for northward expansion, while on the other a few daring critics labeled these claims a pack of lies. One particularly outspoken detractor, Governor Joseph de Faini of Nueva Vizcaya, had taken testimony from Fathers Canals and Reyes as the two gray-robes passed through Durango on their way back to the college. They attacked Gálvez' propaganda head on, chronicling the atrocities committed on Sonora's miserable populace by rebel Pimas, Seris, and "the ferocious Apaches." The gold strikes had been vastly exaggerated. From their report one got the impression that never had conditions in Sonora been worse. [97] To get the facts Bucareli demanded reports from almost everyone. He dispatched Colonel Hugo O'Conor, red-headed Irish wild goose, to take stock of the military situation in the north. He instructed the loose-living governor-designate of Sonora, don Mateo Sastre, to find out if the Seris were indeed pacified, if the Cieneguilla strike was a bonanza or a bust, and how significant were the wanderings of Father Garcés. The friars had mixed feelings about the new viceroy. Their planned expansion to the Gila River, which lacked only the signature of the Marqués de Croix, Bucareli shelved for further study. [98] José de Gálvez had assured Father Buena that he would not forget the friar's recommendations, but when the visitor general left the capital on February 1, 1772, he had yet to act. On the positive side, Viceroy Bucareli seemed to be more conservative, not as committed to Enlightenment reform as Croix and Gálvez. Presumably he would look more favorably on the missionaries' bid for a return to pre-1767 normalcy. They had known in 1767 that the new system would not work. As spiritual ministers only, they could not sustain ex-Jesuit missions on the Sonora frontier. For a year their Indians simply ignored them. When Gálvez saw the folly of it, the archreformer backed down. He put mission economics back in their hands. For their part they sought to bury once and for all the reformers' doctrine that mission Indians had civil rights. They also wanted a larger annual stipend, two missionaries at every mission, less interference from the secular clergy, mission guards, deliverance from Pimería Baja—all of which they would lay before Viceroy Bucareli. While they worked for a return to the traditional paternalism, convinced that it was in the Indians' best interest, a recurrent apocalyptic vision haunted them. It caused all other considerations to pale. It gave Father Roche nightmares. They could fight the reformers—even one in their own ranks—but they could not fight the Apaches. So long as God permitted this scourge to fall upon them, so long as the military failed to restrain the invaders, the specter of Soamca, of missions in utter ruin, would walk at their shoulder. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

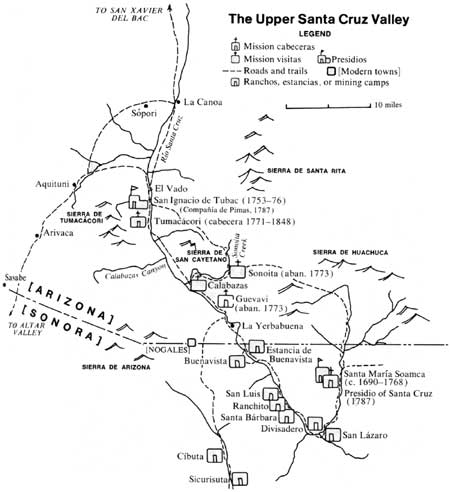

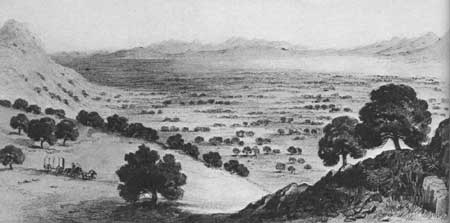

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||