Contents Foreword Preface Jesuit Foundations Gray Robes for Black 1767-68 The Archreformer Backs Down 1768-72 Tumacácori or Troy? 1772-74 The Course of Empire 1774-76 The Promise and Default of the Provincias Internas 1776-81 The Challenge of a Reforming Bishop 1781-95 A Quarrel Among Friars 1795-1808 "Corruption Has Come Among Us" 1808-20 A Trampled Guarantee 1820-28 Hanging On 1828-56 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

EVER SINCE 1701 when the Jesuit explorer Eusebio Francisco Kino crossed the lower Colorado in a man-sized Indian storage basket lashed to a raft and spent the night on the opposite bank, overland communication and supply between Sonora and California had been a goal of frontier promoters and imperial strategists. A generation later Captain Juan Bautista de Anza the elder pledged to explore the Colorado and beyond. In the 1740s Father Jacobo Sedelmayr had exchanged gifts with the Yumas. But not until Russians and Englishmen supplied the requisite threat did the Spanish government move. In 1768 José de Gálvez had arrived on the scene convinced that he could transform barren Baja California into a base for the occupation of Alta California. But the peninsula beat him. To nourish San Diego and Monterey would require supply by sea more than a thousand miles up the Pacific coast against prevailing currents—or a road overland from Sonora. [1] On their march north to San Diego soldiers of Gaspar de Portolá's contingent had startled some Indians. Word of the encounter, of "white men with long clothing and a wooden thing also long with iron on top," passed from tribe to tribe eastward across the desert. Anza the younger heard about it at Tubac and Father Garcés while trekking westward from San Xavier. [2] Both the captain and the friar recognized the import—by retracing the route this news had traveled one could intersect the trail of Portolá's men and link Nueva California with Sonora. The friar took the initiative. Anza thought Garcés a fool to wander alone and unprotected among the heathens. Worse, this simple rustic from Spain who had such confidence in his ability to get along with Indians could inadvertently stir up the tribes or get himself killed. Anza had enough to worry about without a roving apostle. The veteran captain of Tubac further resented the friar's constant meddling in military affairs, his recommendations concerning presidial locations and strategy. Move the Tubac and Terrenate garrisons forward, urged Garcés, carry the war to the Apaches and stop hiding behind the missions, open the Gila route to California and New México, drive off Englishman and Russian. The missionary defended himself. It was not so strange, he averred in a letter to Viceroy Bucareli, "that a poor friar should involve himself in these matters, since they all pertain to the preservation of my pueblos and to the service of both Majesties which we all should promote." The way Anza felt about the missions, or professed to feel late in 1772 when he branded them useless, prejudicial, and tyrannical, must have affected his relations with Garcés and the other friars. Even the two soldiers stationed at San Xavier proved a source of friction. Fray Francisco thought the military, not his poor mission, should provision them. Anza disagreed and threatened to recall them. Garcés complained to Bucareli. [3] At the same time, the road to California drew them together. It stirred Captain Anza's family pride and offered him a dramatic opportunity to serve the crown and win promotion. Father Garcés, by his well-publicized wanderings, had shown the way to the Colorado: the Indians on its banks were friendly, the river fordable, Monterey only days beyond. It was the lonely labor of Garcés, the Franciscans proclaimed, that inspired Anza to propose an expedition. [4] Viceroy Bucareli took a personal interest. He fussed when copies of the Garcés diaries did not reach him promptly. High-level hearings, reports, and more reports followed, and finally viceregal approval. Anza and Garcés with a small pilot expedition would attempt to open the road. [5] Anza had no trouble filling his quota of twenty volunteers from the Tubac garrison. In December, 1773, the proud, Sonora-born frontier officer rode to the mining boomtown of Cieneguilla to meet the Spaniard who had been appointed interim governor of the province, Lieutenant Colonel Francisco Antonio Crespo. To cover for the men he was taking with him Anza wanted twenty replacements, presidials, not raw recruits. Crespo complied. He had orders from the viceroy. Besides, detaching men from existing garrisons saved the crown the additional cost of recruits. [6] Even with Governor Crespo's support Captain Anza had to forage for provisions and animals—pinole, flour, beans, tools, ammunition (to be used only in self-defense), glass beads and tobacco for the heathens, 65 beef cattle, 140 riding horses, and enough pack mules. The plan was to proceed north to San Xavier and leave from there with Father Garcés and his Gila Pima friends leading the way over a route he had already traveled. It miscarried. On January 2, 1774, four days before the date set for departure, a large Apache raiding party with an unerring scent for horseflesh galloped down on the Tubac caballada. "Even though the guard defended it with the utmost vigor and courage," wrote Anza, "they could not prevent them from stealing some one hundred and thirty animals." If the friars were discreet, they kept their sarcastic observations to themselves. Anza was in no mood. The plan had to be changed. The column, mounted on what animals were left, would head southwest for the Altar Valley in hopes of recouping the lost animals on the way. [7] That, Garcés pointed out, meant a detour of fifty-two leagues, some one hundred and thirty-five miles. Saturday, January 8, swearing mingled with blessings, friars with muleteers. Dogs, children, and chickens scurried, keeping barely out from under foot. They were about to set forth. That morning all the participants jammed into the Tubac church: Anza and his twenty presidials, looking as much like regulars in His Majesty's service as they ever would, one California soldier sent by Bucareli to show the way from San Diego to Monterey, an interpreter who knew Piman, an Indian carpenter, five muleteers, two of Anza's servants, and two friars. As a companion for Garcés, Father President Ramos had chosen gritty Fray Juan Díaz, survivor of almost six years among the unruly natives of Caborca. Moreover, Díaz' hand was legible, he knew something of astronomical observation, and he could draw a map. The thirty-fourth member of the expedition, Sebastián Tarabal, an Indian runaway from San Gabriel in California, who had just made the crossing from west to east, would join them at Altar, "one of those rare occurrences that Providence bestows." Three more friars assisted at Mass that morning, Tumacácori's Clemente and Moreno, and another member of the mission of 1769, Fray Juan Gorgoll, who since 1772 had served as compañero to Díaz at Caborca. Tall, red-faced, with a small wart on his nose, Gorgoll would fill in for Garcés at San Xavier. The congregation heard the Holy Trinity and the Blessed Virgin Mary in her Immaculate Conception proclaimed as guardians of the expedition. After Mass, Tubac resembled a mob scene. By one o'clock the column had formed up. According to Father Díaz, "a vigorous volley and repeated 'Vivas' well manifested the joy at the auspicious beginning of a journey which may yield such glory to God, happiness to souls, and honor, merit, and luster to our Catholic monarch." [8] They camped that first night almost within sight of the presidio, a league north at the ford where the road to San Xavier crossed the meandering river. Next day, skirting round the craggy Tumacácoris they struck southwest for Arivaca, site of the visita destroyed in the Pima revolt of 1751. Twenty weeks later they were back. They had seen the Pacific. They had done it, linked Sonora with California overland. In Mexico City, Viceroy Bucareli exulted.

He recommended a lieutenant-colonelcy, and for "each of the soldiers who so faithfully accompanied him in this prodigious undertaking" a life-long monthly pay raise. [9] Ex-Texas governor Hugo O'Conor, "capitán colorado" the Indians called him because of his ruddy Irish face and his red hair, was not that interested in a link between Sonora and California. More important to the defense-minded comandante-inspector of all the presidios was the location of Tubac's garrison. The royal presidial Reglamento of 1772, a result of the Marqués de Rubi's general inspection of 1766-1768, called for a realignment of the cordon from the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of California. The invading barbarians—mainly Apaches—must be turned back. That task absorbed O'Conor, as well it might have, but in the opinion of expansionists it limited his vision. If he moved a presidio, it was to place it and the line in a more effective defensive posture, not to expand the empire. That he left to Viceroy Bucareli. [10] The red captain applied himself first to the central and eastern sectors of the frontier, reforming the line and chasing hostiles. [11] In 1774 from his headquarters in Chihuahua he sent an advance man to Sonora, Deputy Inspector Antonio de Bonilla, who reached Tubac in May just before Captain Anza was due in from California. Eager to get on with his business, the widely traveled young staff officer sent a half dozen Tubac soldiers to intercept Anza. At Tucson before daylight on May 26 they handed their captain an order to report immediately. What was so urgent? They could not say. So Anza, the six soldiers, and Father Díaz, who assured them that he could keep up, rode light for Tubac, fifty miles, and reined up in front of the captain's quarters at sunset. The rest of the weary caravan made its appearance amid vivas, dust, and tears next day at noon. Whether the officious Bonilla joined them in the church for a Mass of thanksgiving no one said. A spit-and-polish regular army man, Bonilla deplored the unmilitary disarray he found on the Sonora frontier. In his general report, which Governor Crespo labeled a pack of extreme exaggerations, he painted a uniformly dismal picture. He degraded the troops and depreciated the enemy. How could the ragged presidial, ill-armed, ill-trained, abused by his officers, hope to defeat the Apache? Only by discipline, subordination, and training. After all, an army was only as good as its discipline. Deployment, too, exercised the deputy inspector. Though the Reglamento left the site for Tubac's garrison open to further study, the Marqués de Rubí had suggested the valley of Arivaca, scene of Bernardo de Urrea's great victory over the Pima rebels in 1752. Bonilla disagreed. He described the valley eight leagues west of Tubac as "large but marshy and unhealthful," better for horses than men. The only advantage he saw was that the silver mines in the area, "La Longoreña, La Dura, etc.," could be worked again. On the other hand, "the Tubac settlement and the mission of Tumacácori will be utterly helpless and without a prayer, and they will be depopulated as soon as the presidio is transferred to Arivaca." Captain Anza gave Bonilla something more to think about. To protect the newly opened route to Alta California the western anchor of the presidial cordon should be set at the junction of the Colorado and Gila Rivers, well above the Rubí line. Therefore, to keep the new line from sagging, Tubac too should move north. Though Bonilla would recommend Santa Cruz, site of an abandoned Sobáipuri ranchería in the San Pedro Valley near present-day Fairbank, he left the ultimate decision to Comandante-Inspector O'Conor. [12] Anza was impatient. Bonilla's presence galled him. He knew a hero's welcome awaited him in Mexico City. While the deputy inspector counted lances and shields and muskets, Anza set Fray Juan Díaz to drawing a map, a graphic record of "what we have accomplished." He meant to present it and the diaries to Bucareli in person, as the viceroy had ordered. Finally Bonilla left. Thank God. But a few days later, a courier rode in with "an urgent and secret order" for Captain Anza. He could scarcely believe it. The inspector was summoning him to Terrenate. Now what? Taking none of his papers, Anza rode the forty-five miles to Terrenate only to find himself placed in temporary command. The unruly Joseph Antonio de Vildósola had been sacked. Bonilla instructed Anza to maintain proper military order until a replacement could be sent. Did he have any idea what the road to California meant to Viceroy Bucareli? But it was no use. On June 8, 1774, a dejected Anza wrote the viceroy from Terrenate. [13] For two months he would be stranded there. Bucareli fumed. How dare they? At once he wrote Commandant-Inspector O'Conor and the governor of Sonora. Let Captain Anza go immediately. "There is no project of greater importance in this province today than the one Anza has just executed with such care." [14] The viceroy had ordered him to Mexico City and come he would. Who did Bonilla think he was? By the end of August, at the height of the rainy season when travel was worst, Anza finally hit the road south. That same month Father Garcés had shown up at Tumacácori to ask a favor. Would Fathers Clemente and Moreno mind copying in a legible hand the last section of his diary? They agreed, dividing the task between them even though Moreno was the better penman. Garcés had problems enough trying to make out his own notes. Anza had left Garcés May 21 in a Cocomaricopa ranchería. Because the viceroy had asked the college to investigate the possibility of direct communications between New Mexico and California, Garcés intended to send a letter to the friars of New Mexico from the Gila via intervening tribes. When the Indians on the Gila who were warring with the Yavapais refused to take the letter, he had ridden alone and trusting northwest to the Halchidhomas. These people lived above the Yumas on the Colorado and maintained friendly intercourse with both Yavapais and Hopis. He ascended the river for several days, gave the letter to an old Halchidhoma, and headed back convinced that the best route to Monterey lay well north of Anza's. [15] The captain would present the diary to Bucareli. But because Garcés did not trust Anza he wrote the viceroy himself from Tumacácori, August 17, 1774. Anza had assured him in front of witnesses that he favored founding at least seven or eight new missions. What story he would tell at court though, Garcés did not know, since he says something different in different company." [16] The people of Tubac and Tumacácori could scarcely believe it. The governor of the province here? Not likely. The Seri wars, administration, and roaming Apaches had long kept the Spanish governors of Sonora in the south. But Lieutenant Colonel Francisco Antonio Crespo, career officer of the infantry regiment of Granada, was of a different stripe. He would see the northern Pimería and the Río Gila for himself. He would teach the barbaric Apaches a lesson, by God. While the redoubtable governor chased shadows to the north with half the Tubac garrison, a reported two hundred and fifty to three hundred Apaches attacked the presidial caballada at dawn November 18, 1774, taking fifty-five head and gravely wounding an Indian auxiliary. That night they came again, but to no avail. The herd had been driven inside the walls of the presidio and the twenty-six soldiers reinforced by settlers. [17] A week later, while Captain Anza belatedly relished the adulation reserved for heroes at the court of México, Governor Crespo addressed Comandante Inspector O'Conor from the crude adobe presidio of Tubac.

Father Garcés had briefed the governor thoroughly. The Tubac garrison should be transferred north a hundred miles to the confluence of the San Pedro and the Gila, near today's Winkelman, right on the Apaches' doorstep. If the hostiles tried to pass to the west, the Gila Pimas and the Pápagos would pick them up—the Gila Pima governor had in fact led a delegation to Tubac to boast of recently having killed twenty of the enemy. Terrenate should move north thirty-five miles down the San Pedro Valley to Santa Cruz, Bonilla's choice for Tubac. Fronteras, farther east, would be placed just where the Reglamento prescribed, at San Bernardino within sight of the Chiricahua Mountains. All needed bigger garrisons. Placed thus they could block three major Apache raiding trails and eventually harry the enemy out of the land. The governor felt obliged to report his thoughts to O'Conor "before the physical construction of presidios is begun." [18] At Altar in mid-December Crespo set down for Viceroy Bucareli his feelings about the second, larger overland expedition to California being planned at court. He favored the more northerly route crossing the Colorado above the Yumas and thence directly to Monterey, the route Garcés thought best. His talk with the Gila Pimas had convinced him that they should have two missions immediately. He agreed that the Yuma crossing and the port of San Francisco had to be secured, but before taking settlers. So much for the road to California opened by Juan Bautista de Anza. Governor Crespo now made his own bid for glory. From the Río Colorado, "according to reports and to conjectures of the Reverend Father Garcés," by traveling north and east one could follow the route of Indian trade goods to the Hopi pueblos and to New Mexico. "I think it desirable that on the return from Monterey these new explorations should be undertaken . . . even if the results we hope for are not realized, a great deal of knowledge of those countries will result." Soldiers, an engineer or two, a surgeon, and of course Father Garcés, should go. Though modesty prevented him from requesting command of the enterprise for himself, he made it clear to the viceroy that he, Francisco Antonio Crespo, stood ready. [19] The ruddy Gaspar de Clemente and his shorter, pale, and pock-marked compañero Joseph Matías Moreno kept up their ministry at Tumacácori and Tubac throughout the eventful year of 1774. They made do on a single three hundred and fifty-peso stipend. Fortunately the harvests were better. Between them that year they baptized twenty-nine persons—Pimas and Pápagos in the two surviving pueblos, gente de razón from Tubac, several of the Indian slaves known as Níjoras traded in the Pimería by the natives of the Gila or Colorado, even a couple of Apache children taken earlier "in just war" by Captain Anza. [20] By early 1775 both friars had left Tumacácori. Clemente, not yet thirty, had lasted two years and several months; he apparently went back to the college, his health broken. For some fifteen or sixteen years he lived the ascetic, disciplined routine within its walls, then dropped from the rolls. Moreno, also listed as accidentado at one stage, stayed in the missions. [21] He labored at Caborca, and with Fray Pedro Font built the stocky, vaulted church at San Diego de Pitiquito. [22] In 1780 he joined Fray Juan Díaz on the Río Colorado. Less than a year later he, Díaz, Garcés, and a fourth friar died in the Yuma massacre. The two young missionaries who took over at Tumacácori early in 1775 had both seen an Indian before. Fray Pedro Antonio de Arriquibar had spent a year in Baja California, Fray Tomás Eixarch about the same length of time in Texas. Almost thirty, chunky and full in the face, Arriquibar was a Basque born in the parish of Santa María Ceánuri two or three hours' ride southeast of Bilbao on the highroad to Vitoria. "The terrain . . . is hilly and broken with very sparse meadows; in general it is of poor quality and would produce little or nothing were it not for the unceasing labor of the inhabitants." [23] Dense oak growth, clear streams, wooden bridges, apples, rain and humidity, every shade of green—the scene of his youth could hardly have contrasted more with the desert Pimería where Fray Pedro was destined to spend the remainder of his life—forty-five years. Arriquibar had entered the Franciscan novitiate in Bilbao at seventeen. Seven years later in Aránzazu he volunteered for the missionary college of San Fernando in Mexico City. Since 1769 he had traveled perhaps ten thousand miles—from the north of Spain to México, from there to Baja California with delays and digressions, then in 1772 when the Dominicans took over, back to Mexico City, in 1774 by transfer to the Querétaro college, and finally to Tumacácori where he hung his broad-brimmed gray hat at least as early as February, 1775. [24] Tomás Eixarch, thirty-one, had black hair, black eyes, and a sallow complexion. He stood no more than 5 feet 2 inches. His hometown, the villa of Liria northwest of the Mediterranean port city of Valencia, reposed in a nearly flat agricultural belt. The weather was temperate and generally clear. In 1759 fifteen-year-old Tomás from "the delicious, happy, and fruitful countryside of Liria" was received into the Order of Friars Minor in Valencia. Ten years hence he sailed with the mission for the college of Querétaro. By 1772 he was in Texas, compañero to a veteran missionary at San Juan Capistrano in the San Antonio cluster. Later that year when the Queretarans gave up their Texas missions he traveled back to the college, only to set out again in 1774 for Sonora. At Tumacácori he ranked his portly Basque compañero. [25] In May, 1775, less than a year since his previous inspection, Father Visitor Antonio Ramos dismounted once again at Tumacácori. There were abrazos. Fray Antonio and Fray Tomás had been neighbors in Texas. The new Franciscan commissary general for New Spain, Fray Antonio Fernández, had called for a progress report on the missions administered by the college of Querétaro. What was their population now? Had there been any spiritual progress among the Indians since the friars took over? Any increase in temporalities? Ninety-one Indians, Pimas and Pápagos, resided at Tumacácori, down seven from the year before, as well as twenty-six gente de razón, up seven. At Calabazas there were one hundred forty-one Pimas and Pápagos. In that lone visita lived "the Indians of Guevavi and Sonoita, desolated by the furious hostility of the Apaches." According to Father Eixarch many Pápagos had been guided to the mission through the apostolic labors of the friars. All the Indians of both villages were well instructed in the Holy Mysteries. "They also recite the catechism in Spanish, though they understand little, for there is almost no comprehension of said language (except in a few cases)." Economically things could have been worse. No one denied that Apache raiding over the past seven years had caused a decline in Tumacácori's community property. Still, the livestock count, thanks to constant vigilance, now stood at about a hundred head of cattle, twelve mares and as many horses, and a thousand sheep. Enough grain and produce were grown to feed the mission. Proceeds from the sale of surplus seed went to clothe the Indians and furnish the churches. The mission's business agent, or síndico, probably Interpreter Ramírez or one of the other gente de razón, had in his possession three hundred and fifty pesos from the sale of provisions to the presidials and settlers at Tubac. That all this was true Fray Tomás swore at Tumacácori, May 12, 1775. [26] For the friars at Tumacácori, Tubac was both a blessing and a burden. A settlement of three to five hundred persons so close did serve as a deterrent to Apache annihilation and a market for mission produce. On the other hand, the settlers and soldiers, with their drinking, gambling, swearing, and wenching, set anything but a good Christian example for the neophytes. Fathers Eixarch and Arriquibar, who were supposed to be missionaries entre infieles, now ministered to more non-Indians than Indians. That year, 1775, of the eighteen baptisms they performed, fourteen were for residents of Tubac. For better or worse Tumacácori and Tubac were one community. They shared the same ministers. Families from the presidio mingled, licitly and otherwise, with the socially inferior mission Indians. Many of them had Indian god children and compadres, though by no means did that imply equality. Rather, it was a Christian duty. Tumacácori and Tubac shared the same river. When its volume dwindled Captain Anza enforced irrigation control. One week the Indians of Tumacácori diverted the flow into their acequia madre, or main ditch, the next week they let it through downstream to the presidio's dam. [27] Mission and presidial herds grazed together. When the mission sold maize, wheat, or livestock to the presidio, some small percentage of Tubac's 20,670-peso annual military payroll ended up at Tumacácori. Petty trade was almost constant, with transactions mostly in goods, not cash. Unless the missionaries intervened, to hear them tell it, the Indian nearly always got the bad end of the bargain. The specific duties of Tumacácori's minister in his capacity as military chaplain had been spelled out in the presidial Reglamento of 1772. In addition to administering the sacraments to military personnel and civilians, keeping the records, and going on campaign when requested to do so, the chaplain was to provide

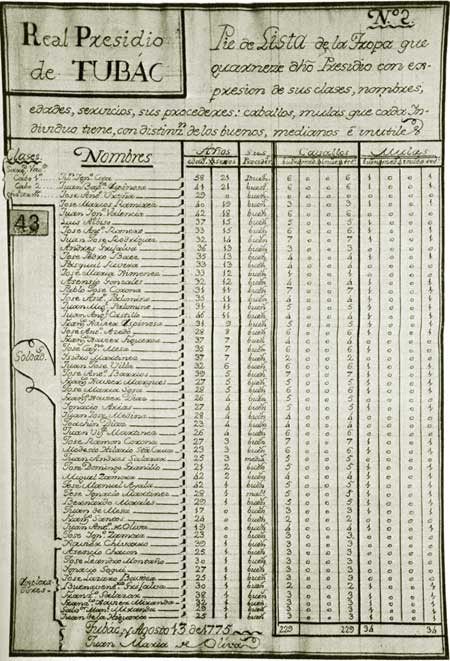

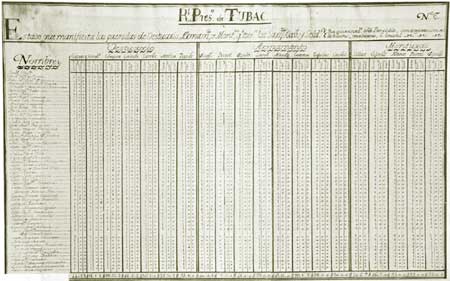

The two friars continued to bury victims of the unrestrained Apaches. That June, Lieutenant Oliva, commanding in Anza's absence, lamented three such casualties that need not have been. The presidial horses and mules had been grazing not far from Calabazas. The corporal of the detachment guarding them had orders to fall back on that pueblo at the first sign of a raid. He chose instead to be a hero. When Apaches appeared over the hill he divided his force and sent some of the men with the herd, which made Calabazas safely. He and the others would kill a few savages. But there were too many, and the corporal died for his bravado. Denied any animals, "their main objective," the Apaches took off. Near Terrenate they reappeared, killed a woman and child and later a soldier, but got no horses. They would be back. [29] In the hot, sticky month of August, 1775, Tubac was astir. As chaplains of the garrison and vitally interested members of the community, Fathers Eixarch and Arriquibar shared the anticipation. Would the government really deactivate the presidio and transfer the garrison? What provision was to be made for the protection of settlers and mission? Soon they might know. The famous capitan colorado, don Hugo O'Conor, commandant-inspector of all the presidios on the northern frontier, was on his way from Altar. For ten days O'Conor and his staff took stock of the Tubac garrison. Their verdict, like Bonilla's, was harsh.

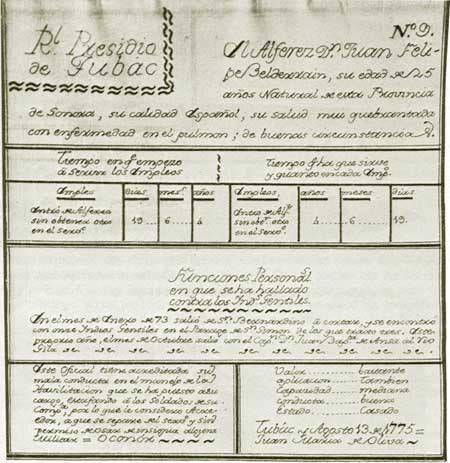

That hardly seemed fair. Perhaps had Captain Anza been present, instead of shaping up his second California expedition at Horcasitas, O'Conor might have tempered his report. The Irishman did laud sixty-year-old acting post commander Juan María de Oliva. Eighteen years in rank, many times wounded, veteran of over a hundred campaigns, the lieutenant was "a daring officer of courage and good conduct, but he does not know how to read or write." The commandant-inspector reserved his special ire for Anza's incompetent and sickly twenty-five-year-old godson, Ensign Juan Felipe Belderrain. Appointed by Anza in 1771 with no previous service, Belderrain was the son of the captain who founded Tubac in 1753 and thereby a member of Sonora's closely knit Basque community. Anza had made him supply officer. Don Felipe had proven a grafter, buying low and selling high to the troops, a practice expressly forbidden by the Reglamento. Without the captain to cover for him, the whole company complained. An audit of the books convinced O'Conor that Belderrain ought to be cashiered and forbidden ever to wear a military insignia. "In addition to his bad conduct and faint-hearted cowardice he possesses many other vices that justify his complete separation from the royal service."

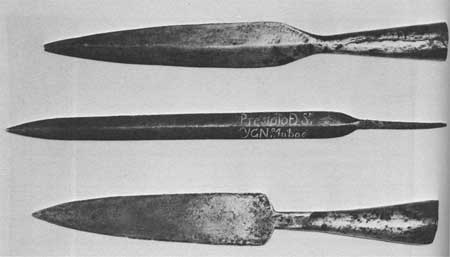

On review the Tubac troop was a sight. The full fifty-six-man company including officers consisted of a criollo captain (Anza's father was born in Spain), a "Spanish" lieutenant and ensign (that is, descended from Spaniards), a sergeant (vacant), two Spanish corporals, sixteen Spanish soldiers, fifteen coyote soldiers (offspring of mestizos and Indians), eight mulatto soldiers, one mestizo soldier, and ten Ópata Indian scouts. One trooper, twenty-eight-year-old José Antonio Azedo, a veteran of Anza's first California expedition, lay ill, completely unfit for service and "without hope of regaining health." Seven others, five of whom had made the California march, deserved honorable discharges because of fatigue and sickness. Instead of presenting a smart appearance in the uniform specified by the Reglamento—short blue jacket with red collar, blue trousers and cape, sleeveless leather cuera, cartridge-box, bandoleer with the name of the presidio, black neckerchief, hat, shoes, and leggings—the whole ragtag garrison looked to O'Conor "practically naked." Nor did their weapons measure up. The four worthless carriage-mounted cannon noted eight years earlier by the Marqués de Rubí were still there. [30] Except for a few made in Barcelona, O'Conor considered the muskets, manufactured in New Spain in a variety of calibers, all but useless. Of lances and swords there was an assortment. Since he expected an arms shipment for all the presidios of Sonora, the commandant-inspector ordered the troop to make do awhile longer. Meantime they must round up another sixty-nine horses and fourteen mules to bring the presidial herd up to seven per man. Saddles and trappings he classed as serviceable, except for the open wooden stirrups. The Reglamento stated closed wooden stirrups. Some strategists, including Rubí, expected the civilian settlers clustered around Tubac, like those of much larger El Paso del Norte on the Río Grande, to form militia units and defend themselves after the garrison was moved away. One look discouraged O'Conor.

O'Conor wanted the presidios of Sonora to fall into a neat line on his map. If he moved Tubac north to Tucson and Terrenate to Santa Cruz, they would line up with Fronteras at San Bernardino. The commandant-inspector had written off Arivaca. Not only was it too far south but its only water, he reported, was a ciénaga that all but evaporated during the dry season. [32] Taking Lieutenant Oliva and twenty of the Tubac garrison with him as an escort, O'Conor forded the river a league north of the presidio and disappeared down the trail to San Xavier. He must see Tucson for himself. Two days later he walked the ground and was pleased. Once a Pima field camp called San Agustín by the Jesuits, the site lay east of the river across from the occupied visita of Tucson. It was nearly flat, somewhat elevated, and open enough to see anyone approaching. Wood, water, and pasturage could be had nearby. A presidio here, O'Conor boasted, would result in "a perfect closing of the Apache frontier." Father Garcés, who had ridden out from San Xavier with the official party, agreed, but only because the comandante-inspector insisted. [33] O'Conor had no use for friars who meddled in military affairs. He had in fact expressed himself on this point a couple of weeks before, and thereby stuck his boot in his mouth. Earlier in the year Garcés had set out for Mexico City to brief Viceroy Bucareli firsthand on his explorations and the need for new missions. When the itinerant friar fell ill at Ures he asked his compañero Fray Juan Díaz to take down his thoughts on everything from New Mexico-California communications to presidial locations. Garcés had been begging since 1768 for a missionary for Tucson. He wanted the presidio placed another fifty miles north at the confluence of the Gila and the San Pedro. When Bucareli passed the Diaz-Garcés letter on to O'Conor for comment, the comandante inspector, instead of taking issue with specific points, impulsively attacked Father Díaz. [34]

At San Xavier that day, Father Garcés evidently won don Hugo over. They reached an accord. Writing to Bucareli, the friar laid on the blandishments. If only the gallant Irish chief had reached these frontiers years before, surely Sonora would not have fallen so low at the hand of the Apache. As for building a presidio at Tucson, that was fine with Garcés, since O'Conor had affirmed that both the Gila and the Colorado would be occupied "at no additional cost to the royal treasury." The Colorado project now seemed assured. But the friar worried about the Gila. He had submitted all the particulars to Bucareli by various channels, "especially when Anza was raising objections." [36] While the commandant-inspector reconnoitered the new sites for Terrenate and Fronteras with half the troop from Tubac, chilling word came from the Gila. Vicente Gaspar, a hispanicized Yuma who had escaped from his Apache captors, told how the hostiles were massing, waiting only for more light from the moon to sweep into the province. Their main objectives, he said, were Tubac and Terrenate, which they intended to destroy completely, and then Cieneguilla. On September 7 they struck. And this time on the first try they overran the entire Tubac caballada. From Horcasitas the furious Captain Anza had to send horses to mount the men he had summoned as an escort. The Apaches, suddenly and happily encumbered by five hundred head, forgot all about Terrenate and Cieneguilla. [37] A lookout on the hill above Calabazas Sunday morning, October 15, 1775, would have seen far below in the valley to the right the squat, gray-robed figure of Father Arriquibar and several other horsemen making for the pueblo. Soon he would have heard the bell. The friar had come to say Mass. Now to the left coming north down the road along the river he would have made out another similarly chunky Franciscan and four soldiers. They too turned off the main trail and rode up to Calabazas. This was Fray Pedro Font, "cosmographer" of the second Anza expedition, which he had left only a couple of leagues behind. Because the commander had forbidden Font to say Mass in camp for fear of an Apache raid, the impetuous friar had ridden on ahead toward Tumacácori. He and Arriquibar embraced. Before midday a dust cloud in the direction Font had come announced the approach of the whole caravan. Out in front mounted scouts scanned for signs of Apaches. Next, leading the vanguard and sitting his saddle like the returning conqueror, rode the bearded Lieutenant Colonel Anza. Then came all manner of men, women, and children, poor people from down the coast recruited to settle the port of San Francisco in California, well over a hundred, all of them outfitted "from shoes to hair ribbons." Some of the men had two and even three children up with them. Behind the rear guard twenty muleteers, most of them green hands, did their best to keep 140 loaded pack mules on the road. And last, as bunched as the vaqueros could keep them, followed all the spare mules and horses. [38] For a colonizing expedition expected to cover a thousand miles to plant a key outpost of empire, the Anza caravan seemed cursed with an inordinate number of broken-down nags. Father Font blamed the commander.

Plucky Pedro Font, sick and out of humor much of the time, would fault the commander all the way to California and back. For his part, Anza resented the barrel-shaped chaplain's ignorance of the frontier. [40] Assigned to the expedition because he could take latitudes, Font kept the adventure's most complete and most human diary. A catalán from Gerona who had crossed the Atlantic on the Júpiter with Garcés but only recently arrived in Sonora, Pedro Font was of medium height but blocky. His face was round and his black hair receding. He was musical and artistic: at the college he had sung in the choir and drawn great illuminated choir books. [41] He had left his mission of San José de Pimas in Pimería Baja in the care of Fray Joaquin Belarde. While Anza was held up a week at Tubac, crowded now with a third again as many people, Font stayed at Tumacácori, mostly in bed suffering from a stomach ailment and diarrhea. Tumacácori in fact looked like a friary. Besides Eixarch, Arriquibar, and Font, Garcés came down from San Xavier and his temporary replacement, ruddy Felix de Gamarra, rode in from Tubutama. The talk over cups of chocolate must have ranged from Spain to California. Companionship of this sort was rare in the missions. Anza had authorization to buy what provisions he could in the missions of Pimería Alta. Tumacácori cannot have offered much. Most of the 355 head of beef cattle, for example, had been driven up from the south. Chaplain Font did at least borrow a set of cruets from Tumacácori and "a supply of hosts for the whole journey." But the mission's major contribution was an individual, a member of the expedition who except for the diary he kept remained almost anonymous in the official correspondence. Father Tomás Eixarch was going. Garcés had arranged it. If it had been left to him, he himself would not have gone with Anza the second time. He and his warm ally Governor Crespo were much more interested in opening a road up the Colorado River to the Hopi pueblos and to New Mexico. The energetic, Spanish-born Crespo, bidding to upstage local hero Anza, had informed the viceroy of his readiness. [42] Garcés from his sickbed in Ures had concurred. Let Anza do no more than convey the colonists to San Francisco.

If, as the viceroy had disposed, Garcés' part in the second Anza expedition amounted to no more than sitting alone with the Yumas on the Colorado, he could add nothing to what was already known. Besides, it was the Gila Pimas and Halchidhomas, not the Yumas, who held the more northerly route he favored. [43] But like it or not Garcés was committed. Bucareli had made it clear: if the friar did not care to serve God and king on the Colorado, that part of the expedition would be scrapped. [44] Oh no, wrote Garcés, "Your Excellency supposed and very rightly that I wanted to have a part in it." He had merely wished to point out that without a companion he could not serve as effectively as he desired. Very well, responded Bucareli, let Father Garcés take a companion. In accordance Anza had outfitted Eixarch with mules, horses, and gear. [45] At Tumacácori the two friars must have reached an agreement. Tomás Eixarch would hold the Yumas' hands while Garcés struck for New Mexico. Anza sent for the friars on Saturday, October 21. During the previous expedition he had taken offense at the meddling of Garcés and Díaz in affairs he considered strictly his concern. This time it would be different. This time the friars would confine themselves to the expedition's spiritual welfare and leave command to him. When he wanted their opinions he would ask. This time, by order of the viceroy, the friars were subordinate. [46] He explained the delay. They were waiting for Sergeant Juan Pablo Grijalva, his wife, and three children to come from Terrenate. Because not enough soldiers were available to give them a strong escort, the family was traveling at night. [47] When the Grijalvas rode in safe late that afternoon, the roll was complete. It now stood at an even two hundred and forty persons—7 officers and friars, 8 veterans from other Sonora presidios, 10 Tubac soldiers making the journey for the second time, 20 recruits, 165 wives and children, and 30 assorted muleteers, vaqueros, interpreters, and servants. They would attend Mass Sunday, and set out Monday morning. Father Font asked Anza if he might use the quadrant to take the latitude of Tubac. He wanted to practice. Having to ask every time galled the friar. "It is certain that the viceroy ordered the astronomical quadrant delivered to me so that I might observe on the way. But Señor Anza, desirous of making himself the author of the observations, immediately took charge of it and did not wish to deliver it to me." [48] At Mass on Sunday Font preached to the assembled crowd. Taking his theme from the Gospel of the day—"Fear not, little flock!"—the stocky Franciscan exhorted them to persevere on the long trek ahead. They should be happy that God had chosen them for such an enterprise.

The unwieldy column began to move out behind the royal standard at eleven o'clock Monday morning, October 23, 1775. The first night, ten miles north at the place called La Canoa, the wife of Vicente Felix died in childbirth leaving him with seven children. Incredibly, considering the high incidence of illness en route, she was the expedition's only fatality. Garcés went ahead to San Xavier with the body. When the caravan reached there on Thursday, Father Eixarch baptized the new infant, while Font married three couples who could not wait till they got to California. From San Xavier they marched past Tucson, "the last Christian pueblo in this direction," and slowly left behind on the horizon the massive, blue Santa Catalinas. A month later they were on the Río Colorado surrounded by hundreds of curious Yumas. [50] The river had not yet begun its awesome seasonal rise. At a place scouted by Anza where the great silty flow divided into three shallow channels they crossed to the west bank. Father Font unsteadily astride a tall horse got wet to the knees. "Since I was ill and dizzy headed, three naked servants accompanied me, one in front guiding the horse, and one on each side holding me on so that I would not fall." The trusting Garcés "was carried over on the shoulders of three Yumas, two at his head and one at his feet, he lying stretched out face up as though he were dead." No one said how Tomás Eixarch made it across. The following day, December 1, with the cold northwest wind kicking up a fierce dust storm, Anza ordered some of the muleteers to build a shelter for Fathers Garcés and Eixarch. Font was in a foul mood. Anza had let the vestments get wet. He had not allowed the friars to distribute gifts to the Indians "for he wants all the glory himself." He still refused to give him the quadrant. Yet he had insisted that Font bring with him his psaltery, a stringed musical instrument, to entertain the Indians, even though so far he had "not even suggested that I play it." Now the chaplain wanted to know what provisions the commander was making to leave two friars among the heathens without a guard. "By this he was very much vexed, and asked me why I was quizzing him in that way, saying that he did not have to report to me." No wonder, wrote Font in his diary, that the Venerable Fray Antonio Margil de Jesús used to pray, "A militibus libera nos Domine," "Lord, deliver us from soldiers." Font and the soldiers and the caravan resumed their march December 4. Besides the two Spanish Franciscans, the little party left behind at Yuma comprised seven persons of varying ability. The three Indians listed as interpreters, who would not lift a hand to help in any other capacity, the missionaries invariably described as very poor Spanish speakers "no matter how many signs they make." The two "muleteers," California runaway Sebastián Tarabal and a young servant who chose not to go on with his soldier-colonist employer, fortunately proved more useful. Fray Tomás would thank God more than once for this nameless lad who could cook and do most anything. But no one objected when good-for-nothing Joseph María Araiza of Tubac, who had volunteered to serve Garcés, begged to go back. The seventh person, a small boy evidently from Tumacácori who came along to look after Father Eixarch's horses, served faithfully the whole time. The day after Anza left, Garcés took a supply of glass beads and tobacco, two interpreters, and Sebastián and set off downriver eager to comply with the viceroy's charge, to talk with the peoples on the lower Colorado and to see "if they were disposed and ready for religious instruction and for becoming subjects of our Sovereign." He would then return to base camp at Yuma and be off toward New Mexico. In the meantime the unsung Father Eixarch settled in. For the second time since their call to Sonora a friar of the Querétaro college had the chance to work for a time among true heathens, to preach the good news in a place where the very name of Christ had hardly been heard. The first, Fray Juan Crisóstomo Gil de Bernabé, had died a martyr. Eixarch ran the same risk.

While Eixarch kept his uncomfortable vigil on the Colorado and Garcés explored, the western Pimas, the "Piatos"—short for Pimas Altos—as they came to be called, once again threatened revolt. Notoriously inconstant, these people of the Caborca area and their relatives up the Altar Valley had run amuck in the bloody uprisings of 1695 and 1751. Some of them had joined the Seris at Cerro Prieto in the 1760s. Incidents in the missions were frequent. When Governor Ignacio Yuburigipsi of Pitiquito mocked Fray Juan Díaz late in 1772, Captain Urrea had stationed at the mission six soldiers from the presidio of Altar. [53] Rumors of an uprising persisted. Bonilla had heard them when he inspected Altar in 1774. Now in January, 1776, Urrea received an ominous letter from Fray Antonio Ramos, missionary at Sáric. His Indians were plotting with a vengeance. Word of it had reached at least as far as Tumacácori. Since the previous August 8, the day he arrived at Sáric, Father Ramos had been gathering evidence of a cabal among his wards. They had assembled unlawfully some distance from the pueblo, and then begun making bows and arrows in earnest. The night of December 10, the son of the mission mayordomo had seen a circle of Indians: in their midst lay war clubs, macanas. The next night the macanas were gone. Later the mayordomo's son accompanied Father Félix de Gamarra as far as Tumacácori. There, he claimed, Miguel Antonio, governor of Tumacácori, had said to him, "Friend, I don't know how you dare live at Sáric, because the people of Sáric have lost their heads—they mean to revolt." Already they had begun dancing in a circle with macanas and masks, "dancing whole days and part of the night." When Father Ramos left Sáric on December 28 to visit Fray Manuel Carrasco at Magdalena, the Indians danced for 24 hours and held nocturnal meetings. Ensign Felipe Belderrain halted at Sáric, January 3, 1776. While watching a dance he noticed a concealed macana fall to the ground. Two days later Ramos returned. Reading the signs, he decided to call the Indians' bluff. After the Mass of Epiphany on January 6, he suddenly let them know that he was on to their plot. His words struck them in the face. When he called in his interpreter and the justicias and got down to cases, Miguel, governor of the visita of Aquituni, confessed. It was true, they planned to rebel. Who had incited them? Manuel, ex-governor of Tubutama. Later that morning Vicente, past governor of Sáric, told who the main conspirators in the pueblo were: Ignacio the carpenter, Agustín the oxherd, and one Francisco who lived next to the Padre's house. The missionary urged the justicias to inform on the others—it would be a shame if the innocent had to pay. Ramos was playing a dangerous game. When he wrote to Urrea that afternoon he pleaded that the captain not implicate him in any way. If the Indians thought he had betrayed them, a few soldiers could not save him.

Captain Urrea, who remembered the charred ruins and mutilated bodies from the 1751 uprising, did not discount the friar's report. He wrote straight away to Governor Crespo, evidently suggesting immediate action. Crespo came in person. In a show of force meant to intimidate the Indians, the Spanish governor of Sonora ordered troops into the pueblos to round up the accused. Years later he described tersely what happened. "With the apprehension of the governor of said Pimería and a few others of the most influential Indians, the country was left in peace." [55] Out on the Colorado, Father Eixarch noted that the river had begun to rise. He was glad to be on higher ground. "I would rather take the trouble of building the house in a safe place, since Commander Anza did not do so, than find myself in sudden peril." He continued to preach peace and monogamy to the Yumas, a tribe that glorified warfare and let a man take as many women as he could handle. They brought him fish and watermelons, begged for tobacco, and learned to cross themselves and to mouth the words "Ave María." He might have been more effective had the no-account interpreters known more Spanish. Yet he said he was content. From the doorway of his house of poles and willow branches he could stand with the morning sun on his face and look down at the Colorado both to the right and to the left of the narrows at Yuma, named by Spaniards the Puerto de la Concepción. Who back in Spain had even heard of Yuma? But here he was, Tomás Eixarch, one lone friar of God amidst a throng of naked heathens. Though he must guard against pride, who had been more blessed than he with an opportunity to live Christ's dictum "Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me"? Still, he never lost sight of the practical.

He was away six weeks, crossing and recrossing the fearsome desert Camino del Diablo, to the missions of Caborca and the Altar Valley. There he confessed, spent Holy Week, and heard the latest news from men of reason. Father Manuel Carrasco had died. After inspecting the Sonora presidios, Comandante-Inspector O'Conor had launched a massive general campaign, a great pinchers movement with troops from Sonora, led by Governor Crespo himself, and from New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Coahuila, all converging on the Apaches of the upper Gila. The offensive had lasted until December. The bodycount, as released by the military, was impressive: 138 Apaches killed, 104 captured, nearly two thousand head of stock recovered. [56] When he got back to the Colorado the raft was waiting. "As soon as I entered the house it filled up with men, women, and children, who manifested the great joy they felt at my return." He gave them tobacco, and for nearly four weeks more he was their Padre. On May 11, he concluded his diary abruptly: "In the morning the weather was fair and I said Mass. Before noon Father Fray Pedro Font returned with Captain Anza and the soldiers who went from Tubac on the expedition." [57] It was over. He did not really want to leave. Orders were orders, Anza reminded him. But no one had heard from Father Garcés. A rumor had him among the Halchidhomas not far off. Reluctantly, the commander agreed to send an Indian upriver with a letter. If the friar did not present himself in three days the column would leave without him. When Garcés failed to show, Font surmised that either he had found a road to New Mexico "as he desired, or, on the other hand, had encountered some great mishap in his apostolic wanderings, since he was now traveling somewhat ill, if indeed he had not died or Indians had not killed him." [58] The indomitable Garcés was in fact at the time enjoying himself, making his way through pine and oak and spring wildflowers in the Tehachapi Mountains of California, three hundred miles northwest. He had detoured from the Colorado west to mission San Gabriel, much to the consternation of California Governor Fernando Xavier de Rivera y Moncada; explored north into the San Joaquin Valley; and was now headed for the Mohave Desert. In the weeks ahead, the roving missionary would recross the Colorado above today's Needles, descend into Havasu Canyon, and end up an unwanted guest of the Hopis at Oraibi on the fourth of July, 1776. Instead of pushing on to Zuni he would double back, to the great disappointment of the New Mexico friars, and return via the Colorado and Gila to his mission of San Xavier. [59] Though Father Eixarch would share little of the recognition and none of the glory, by his patient ministry to the Yumas the missionary of Tumacácori had made possible one of the epic journeys of North American exploration. At Caborca, Eixarch heard news that made him pale. The swaggering don Felipe Belderrain, still ensign of the Tubac garrison thanks to Anza's influence, rode in May 24 to report that nothing remained of Tumacácori. The Apaches had carried off everything. The cavalier way he described the tragedy appalled Father Font. Next morning Belderrain entered a room where the chaplain and others were talking. Without greeting Font, the cocky officer began relating the details "with great coolness, and as if boasting." All the Apaches had left to do was carry off the women. That did it. Font could contain himself no longer.

During lunch the anxious Eixarch asked Anza for some saddle horses so he could return immediately to Tumacácori. "To get rid of him," said Font, the commander consented. Fray Tomás then suggested that the lad who had stayed on the Colorado and served him so well deserved payment. Anza declined, and that set Font off again. Later in the afternoon Eixarch departed in the unpleasant company of Ensign Belderrain. Though he probably knew by then that the officer had exaggerated the attack just to bait Font, he wanted to get back to his mission. When he did, he found it and Father Arriquibar much as he had left them seven months before. The story that Tumacácori had been utterly destroyed in 1776—picked up as fact by historians using Font's diary—was Belderrain's idea of a practical joke. [60] Back at Tumacácori after a seven-month absence, Fray Tomás Eixarch stayed hardly long enough to tell Father Arriquibar all his stories of the Yumas. By late summer, 1776, he was living at the impoverished visita of San Antonio de Oquitoa and commuting as interim chaplain to the Altar garrison down-river. There he served out the remainder of his required ten years, counting his earlier stint in Texas, and in 1781 retired to the college. He did not ask to return to Spain. At a meeting in Guadalajara on January 13, 1783, the provincial and definitory of the Franciscan province of Jalisco approved the petition of Tomás Eixarch to join their province. During the mid-1780s he lived a less strenuous religious life at the convento of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción in Acaponeta on the coastal highway about half way between Tepic and Mazatlan. In 1790 his superiors named Fray Tomás, then forty-six, guardian of the friary at Amacueca, south of Guadalajara. How long he lived after that, solo Dios sabe. [61] A week after Francisco Garcés returned from his incredible two thousand mile odyssey, he sat down at Tumacácori, weary but grateful, and scrawled a letter to Fray Diego Ximénez Pérez, guardian of the college. He still feared that Anza would urge missions on the Colorado but play down the Gila. Garcés of course pled for "the spiritual welfare of both rivers and of the Pápagos as well." Don Hugo O'Conor had assured him of two presidios, one for the Colorado and one for the Gila. The friar wanted to talk again with the comandante inspector face to face: "One cainnot put everything in writing." He would gladly go to Mexico City if that would help. But changes were afoot, changes that not even the trail-wise Franciscan could foresee. [62] As Spain squared off for a New World showdown with Great Britain, her northern frontier, from the Californias to the Mississippi, appeared frightfully vulnerable. Apache and Comanche barbarians made a mockery of what imperial defenses there were. As visitor general, José de Gálvez had already suggested the solution—a unified northern command, something less than a separate viceroyalty but more than a defensive alliance of provinces. For Sonora and the northwest, the grand design included an intendancy and a bishopric. In 1776, as minister of the Indies, Gálvez followed through. | ||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||