Contents Foreword Preface Jesuit Foundations Gray Robes for Black 1767-68 The Archreformer Backs Down 1768-72 Tumacácori or Troy? 1772-74 The Course of Empire 1774-76 The Promise and Default of the Provincias Internas 1776-81 The Challenge of a Reforming Bishop 1781-95 A Quarrel Among Friars 1795-1808 "Corruption Has Come Among Us" 1808-20 A Trampled Guarantee 1820-28 Hanging On 1828-56 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

HIS LOOSE-FITTING GRAY SACKCLOTH habit made him appear bigger than he really was. A healthy ruddiness colored his fair skin. Of medium build, blue-eyed with sandy hair, Narciso Gutiérrez always looked as though he had been out in the sun. His beard was light and he had a long nose. He was, as one might have guessed, from the north of Spain, from the ancient city of Calahorra, birthplace of the Roman Quintilian. [1] In the fall of 1765, when Gutiérrez was born, the Jesuits still administered the missions of Sonora: in the summer of their expulsion he had barely begun to walk. About the time the Yumas revolted and put to death four friars on the Río Colorado, Spanish Franciscans of the province of Burgos invested sixteen-year-old Narciso Gutiérrez with the habit of Saint Francis in the venerable Convento de San Julián at Ágreda, a couple of days south of Calahorra. A village of several hundred houses on both banks of the northward-flowing Río Queiles, Ágreda looked up to the great rounded mountain called Moncayo. The climate was clear, fresh, and healthful, the soil fertile, and, in the opinion of at least one traveler, the artichokes were "without equal." [2] Even then Ágreda had a tie a century and a half old with the northern frontier of New Spain. Young Narciso knew the story. A talented and mystical Franciscan nun, María de Jesús, youthful abbess of a local convent, had made a series of miraculous visits in the 1620s to preach the Gospel to the Indians of New Mexico and the Plains. Fray Alonso de Benavides, missionary propagandist par excellence, had interviewed beautiful Mother María in Ágreda and had used the story for all it was worth to promote his order's missions in New Mexico. By Gutiérrez' day the Franciscans had been urging the canonization of Sor María de Jesús for more than a century. If not yet in the eyes of Rome (her cause was still pending in 1973), to any agredeño she was a saint. It was her famous book, La Mística Ciudad de Dios, that Fray Juan Crisóstomo Gil de Bernabé had with him as a companion at lonely Carrizal. The Seris buried the book with their missionary's broken body. [3] While Father Barbastro and Bishop Reyes were vying for control of the Sonora missions, the college of Querétaro had fallen on hard times. Unceremoniously divested of their eight heathen missions, the superiors had moved to intensify the college's ministry to the faithful. In 1785 twenty-three friar recruits collected in Spain by Father Roque Hernández joined the effort. In 1786 fourteen of them died, most while ministering day and night to the victims of the famine and "universal epidemic" of that year, a disease complex that evidently "included at least typhoid, dysentery, pneumonia, and influenza." [4] A roll call at the college in December showed a total of thirty-eight surviving priests, but precisely half were "unfit for missionary duty because they are ill, incapacitated, or too old." [5] Supported by a ringing plea from the grateful city government of Querétaro, the college secured from the audiencia of México—ruling ad interim after the death of Viceroy Bernardo de Gálvez—and from the archbishop approval to send another recruiter to Spain. Gaunt, long-nosed Fray Juan Sarobe, veteran of the Júpiter's 1763 crossing and one of the original fifteen in Sonora, now sailed back across the Atlantic. In Madrid in August, 1787, he petitioned the king for a mission of twenty-five priests and two lay brothers. To dramatize the urgency of his request he told how the Yumas had massacred their friars, how the college was bound to loan eight missionaries to the custody of San Carlos, and how the epidemic of 1786 had practically wiped out the last contingent from Spain. On September 26 the Council of the Indies reported in favor. The business of recruiting would take Sarobe two years. While he was in Spain Charles III died and Charles IV ascended the throne, the French stormed the Bastille, and the United States ratified a federal constitution. On a 165-day swing through the conventos of northern Spain he managed to sign up eight solid candidates and to interest others. Then, while the bureaucracy debated whether or not he should embark his mission piecemeal, Sarobe saw his recruits despair. Finally, in April, 1789, he put five aboard the frigate San Juan Nepomuceno at Cádiz and bid them Buen viaje. They sailed on the 17th, and he went back to work. The announcements he had sent out began to pay off. Four friars were en route from Mallorca, one was coming down from Galicia, others were on the roads from Burgos, Palencia, and Zamora. Narciso Gutiérrez, three months shy of twenty-four and not yet ordained, received his patente at the magnificent Franciscan convento in Santo Domingo de la Calzada, rebuilt in 1571 after a plan supplied by Juan de Herrera. Cádiz lay more than five hundred miles south. Fray Narciso set out in early July, made good time, and checked into the government hospice at the Puerto de Santa María across the Bay of Cádiz on August 2. A dozen recruits greeted him. Another eight arrived in the following weeks. Father Sarobe, who had not been well, would sail in December, 1789, with twenty-one friars, one short of his full quota. Meanwhile he had to see to their outfitting. Because the government underwrote the recruiting, maintenance, and travel of the friars, Father Sarobe painstakingly recorded his own and his recruits' every expense. Each man signed a statement of his travel expenses en route to the Puerto de Santa María, in the case of Narciso Gutiérrez from La Calzada via Madrid, 699 reales. The padre colectador kept track of charges for laundry, lamp oil, shaves, printing of patentes, and postage. Just before they sailed each recruit acknowledged receipt of

Sundries included bandages for bloodletting, razors, combs, pens, penknives, inkwells, paper, scissors, 2 tin-plated biscuit crates, Mallorca biscuits, 2 liquor crates, brandy, rota wine, Pedro Jiménez wine, lemon syrup, grape verjuice syrup, and one pair of wool stockings for a sick friar. The port authorities permitted the ailing Father Sarobe to take along a servant to look after him and the other indisposed religious. When the private merchantman El Dragón put to sea December 8 they and all their gear were aboard. [6] Sarobe's condition worsened. Off the coast of Yucatan the veteran missionary died. They buried him at sea. [7] On March 23, 1790, without their colectador, the Spanish recruits reached the college and fell on their knees in thanksgiving. Their arrival doubled the number of able-bodied workers. While the moribund Custodia de San Carlos lingered in Sonora they devoted themselves to home missions. By the summer of 1794 the ruddy Narciso Gutiérrez, still not twenty-nine, was ministering to heathens at poor Tumacácori. If only the friars of Ágreda could see him now. The dissolution of the custody did not bring on the millennium. The king's decree of 1791, as usual, was only provisional: the missionaries of Pimería Alta should indeed return to the tested pre-Reyes method, but only till a better one came along. The reformers, it seemed, never slept. This time the threat came from the commandant general, once again independent of the viceroy. As part of his campaign to improve government in the Provincias Internas, Canary Islander Pedro de Nava ordered that the missionaries surrender all control over temporal affairs, that they be supported instead by an annual tribute of half a fanega of maize or twelve reales from each Indian head of family, and that their missions be turned into doctrinas, sort of half-way houses of new Christians on the road to secularization. To the Queretaran friars it was as if the clock had been set back to 1767. Father President Barbastro appealed. Perhaps such measures would serve to improve conditions in the moribund non-missions farther south, but they would surely ruin the active missions, the conversiones vivas, of Pimería Alta. Once again the Father President reiterated the need for a missionary to be both spiritual and temporal master of his mission and warned of prematurely emasculating the father of unprepared Indian children. Nava took note and suspended the order in Pimería Alta, for the time being. [8] Plainly the college of Querétaro had to shore up relations with the commandant general and convince him that the friars knew what was best for their missions. The threat from without was only half the problem. Ever since the dissolution of the custody the superiors at the college had been hearing distressing reports of misconduct by their missionaries in the field. Barbastro, it was alleged, had let matters get out of hand. Not only did he reside far from Pimería Alta at Aconchi, where he was preoccupied and oblivious to the widespread abuses of his men, but also during the custody fight he had conditioned himself to look the other way in the case of friars who supported him. Some of the new arrivals complained that the entrenched old guard treated them like peons. Stories of undisciplined friars mixing with money, commerce, and women were too frequent to ignore. [9] When the college master of novices, Fray Antonio Bertrán, returned from a home mission in Sinaloa, he confirmed the worst. He had interviewed a number of upright Christian gentlemen who had seen with their own eyes examples of the laxity prevailing in the missions of Sonora. One wealthy merchant of Sinaloa alleged "that all was evil, dissolute, and fraught with licentiousness, and other ugly pieces of news." Bertrán singled out several individual friars, about whom he had heard specifics, among them Fray Narciso Gutiérrez of Tumacácori. Gutiérrez, compañero to old Baltazar Carrillo, had written to another of the new young missionaries a most unfraternal, indiscreet, and serious letter. [10] It was time to act. To negotiate with the commandant general, to clean house in the missions, and to rekindle zeal for converting the heathen, the guardian and discretory of the college commissioned a Father Visitor. They chose carefully. Thirty-five-year-old Fray Diego Miguel Bringas de Manzaneda y Encinas, the college's procurador, forceful, courtly when circumstances demanded, widely read in mission administration but never a missionary entre infieles, had ties with no faction. A criollo born in Sonora, he could presumably maintain impartiality in dealing with both los viejos—the veterans, mainly members of the mission of 1769—and los nuevos—the new arrivals, most of the mission of 1789—and with cliques of Spanish paisanos. Furthermore Fray Diego Miguel, a graduate of the University of Mexico, had already published several moral tracts and sermons. Fully briefed, he left the college April 16, 1795, with nine friars assigned to serve internships in Pimería Alta, enough finally to put two religious in every mission. [11] Late in May, Bringas held preliminary talks with Commandant General Nava, who received him civilly in the villa of Valle de San Bartolomé. Their conversation touched on almost everything that interested the college of Querétaro: the status and financing of the present missions, the founding of new missions, the need for military support, Father Bringas' proposed visit to the Gila River Pimas, the possibility of Queretaran friars doubling at Tucson, Janos, and Bacoachi as presidial chaplains and ministers to the Apaches of the neighboring peace camps, and even the defensive strategy—suggested by the Jesuits thirty years earlier—of moving Pápagos into the deserted San Pedro Valley. [12] Later, when he had completed his visitation and seen the frontier for himself, Father Bringas would report back to the commandant general and make proposals. In Pimería Alta the friars awaited the visitor's coming with uneasy excitement. They knew he had the authority to discipline, transfer, or return any of them to the college. He carried a patente naming a new Father President: some questioned whether the rugged Barbastro, after nearly twenty years as superior in the field, would yield gracefully. For his part, Barbastro tried to put the Father Visitor at ease, writing him that the visitation would not be as trying as some would have him believe. Still, the old missionary could not resist lecturing Bringas on the virtue of experience. As any good doctor knew, it was better to hold off prescribing medicine until one had determined the nature of the disease. [13] When the visitor finally reached Aconchi in September, Barbastro made him welcome. The two grayrobes discussed Barbastro's important work with the Indians of Aconchi, his nurture of a chapter of the lay Third Order of St. Francis, and the desirability of a missionary superior who lived in Pimería Alta, not a hundred miles south. Father Barbastro approved of the college's selection, Fray Francisco Iturralde of Tubutama, enduring veteran of eighteen years in Pimería Alta and Barbastro's unofficial resident deputy in those missions. Father Visitor Bringas notified Iturralde immediately. Taking leave of the deposed Barbastro, he summoned his courage and rode on to Pimería Alta. He remembered the Father Guardian's admonition: that he compose the friars' differences discreetly and restore fraternal peace among them, at the same time making clear to them that "they are the crown of this our college." [14] From Tubutama Father President Iturralde, feeling stronger after an illness, wrote that he would meet the visitor at Tumacácori. There, the first week in October, the two superiors conferred in private about the full range of mission crises. One involved Narciso Gutiérrez, already accused of conduct unbefitting a friar. Tumacácori's long-time missionary Baltazar Carrillo might not last the month. Young Gutiérrez, the visitor warned, must not be permitted to succeed Carrillo or anyone else: he was not suited for the missions. Perhaps the best solution in the event of Carrillo's death would be to transfer him to Tubutama as Iturralde's compañero. There the Father President could keep an eye on him. After their talks Iturralde returned to Tubutama and Bringas rode north to San Xavier del Bac and to the Río Gila beyond. Even though symptoms of Spain's flagging strength in North America—her inglorious withdrawals before England in the Pacific Northwest and before the United States in the Mississippi Valley—were perfectly evident to imperial observers by 1795, the college of Querétaro looked the other way. It was as if the friars still lived in the late 1760s and the 1770s, the last great era of expansion, the years in New Spain of José de Gálvez and Viceroy Bucareli. Stubbornly, they clung to their proposal to found new missions among the Pápagos, Gila Pimas, and Cocomaricopas, Indians whom the general command considered non-strategic in the 1790s. As he rode north from Tumacácori down the semi-arid Santa Cruz Valley, still green in early October, 1795, Father Visitor Bringas felt confident that he could bring about a renaissance of missionary expansion in Pimería Alta. He had reason. Commandant General Nava had granted him permission to personally reconnoiter the Gila River. At San Xavier del Bac swarthy, bushy browed Fray Juan Bautista Llorens had been wooing native delegations from the Gila and working with the Pápagos who flocked in to his mission seasonally, from October to February and from May to the end of July. [15] The new captain at Tucson, a vigorous forty-year-old frontier veteran, agreed with Father Bringas. Don José de Zúñiga, former captain at San Diego in Alta California, enjoyed the distinction of having got on well even with Father Serra. He was all for expansion. The previous spring in fact he had led the long-delayed initial expedition from Tucson to New Mexico and back. [16] A force of a hundred and fifty men, presidials and Indian auxiliaries from half a dozen garrisons, had rendezvoused April 9 at deserted Santa Cruz in the San Pedro Valley. Twenty-five were Pima foot soldiers from Tubac. More or less following the route of Captain Echeagaray seven years before, the column struck northeastward for the Gila and Río de San Francisco. In three weeks, thanks to his Apache scouts and a copy of Echeagaray's journal, Captain Zúñiga entered the pueblo of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Zuñi to considerable fanfare. He wrote the governor of New Mexico, waited a week for a reply that did not come, and returned to Tucson. Zúñiga apologized to Commandant General Nava for his failure to kill more than five Apaches en route. Nava suggested that he go back again and more fully identify the trail. That would make it safer for pack trains traveling between Tucson and Santa Fe, a journey that should take no more than five weeks. But the scheme was unrealistic. The military could not possibly police a difficult new trail through hostile territory. Nor was it worth the risk to merchants of either province. No one used the Zúñiga trail. [17]

The captain provided Father Bringas and party with an escort for their October excursion to the Gila Pimas. Following the traders' desert highway northwest from Tucson, the wide-eyed Father Visitor, Llorens, and Fray Andrés Garaygorta passed by jagged Picacho, explored and sketched the Casa Grande, and, like the Jesuit Kino a century earlier, greeted throngs of heathens in river-bank rancherías near present Sacaton. Bringas was elated. These Indians were clamoring for missionaries, missions, and baptism on the spot. He "personally counted" 1,500 of both sexes, a third of them men capable of bearing arms. He made notes on their way of life, the terrain, the flora and fauna, as well as neighboring tribes for a presentation to Commandant General Nava.

With all the facts he needed to convince the commandant general, Bringas the apostle and imperial strategist rode back jubilantly to San Xavier. From there he cut south across the eastern Papagueria to resume at Sáric the unpleas ant business of his visitation. [18] The untoward spectacle of friars at one another's throats may have had a demoralizing effect on some of the mission Indians and settlers: others surely enjoyed it. It all began when Father President Iturralde attempted to fill the vacancy created by the death of old Baltazar Carrillo at Tumacácori and unsuspectingly touched off among the religious an open display of what he himself politely termed "human frailty." During the two years following Carrillo's death, the people of Tumacácori and Tubac saw a succession of five missionaries, not one of whom, except Narciso Gutiérrez, was happy at the mission. The first, well-built, eagle-faced, fifty-five-year-old Florencio Ibáñez, the Father President assigned out of spite. "This is a Father," Iturralde had confided to Bringas, "whom the Lord has placed here to exercise the Old Man [Barbastro] and also the rest of us, particularly those who are closest." This friar had continually nagged Barbastro to let him return to the college, but when the opportunity came he would not hear of it. He was, in Iturralde's opinion, not fit to be alone in the missions or in anyone's company. But since he did not now want to retire to the college, Iturralde was stuck with him. [19] A born troublemaker according to Iturralde, Ibáñez was also a musician, an artist, and a poet. Like Fray Pedro de Arriquibar, he had reached America in the mission of 1770 to the college of San Fernando, where he excelled in the choir and in painting choir books. From 1774 to 1781, he served as a choirmaster and Latin teacher in the Franciscan province of Michoacán. Joining the college of Querétaro, he had come to the Pimería by 1783. Most of the time since then he had spent at Sáric, twenty miles up the Altar from Tubutama and Iturralde. He had built a church there, and he had quarreled with his brethren. By December of 1795, Ibáñez was minister at Tumacácori. [20] Because Fray Narciso Gutiérrez had not been well, the Father President still had not removed him. Besides, Ibáñez and Gutiérrez deserved each other. Relations between the two friars were anything but cordial. Five months earlier Ibáñez had roasted Gutiérrez in a letter to the college. So materialistic was the new young friar, claimed Ibáñez, that "he would abandon a guest in mid-sentence to prevent a half-real from escaping him." Shortly after Gutiérrez had arrived at Tumacácori, he had convinced Father Carrillo to fire the mission mayordomo for dishonesty. He himself had then taken charge of economic affairs, keeping "all the keys...but those for the livestock," and the sick old Carrillo had let him have his way. Evidently Gutiérrez wanted to build the new church so long overdue at Tumacácori. When former Father President Barbastro avoided the issue—allegedly to spare Carrillo the strain—and told Fray Narciso to concentrate on learning Piman, the impatient young friar had fretted and talked of leaving. [21] His objectionable behavior, Ibáñez hinted, had driven Carrillo to the grave. [22] At Tumacácori, Gutiérrez prepared "a bed of fleas" for Ibáñez. Even before the older friar arrived, Fray Narciso had prejudiced the mission Indians against him. Afterwards, alleged Ibáñez, he put four of them, including Tumacácori Governor Luis Arriola, up to fleeing to Father Visitor Bringas in protest. The new Father had pillaged the mission, they told the visitor. Furthermore, he made them get up at the crack of dawn for Mass on work days. In his own defense, Father Florencio pointed out in another letter to the college that he was only following Bringas' instructions. Ordered to pay a thousand pesos each to San Xavier and Cocóspera, he had found in the Tumacácori storehouse a great surplus of clothing, which he sold at cost plus costs to those two missions and to Sáric. As for the other complaint, Bringas had told him to teach the Indians to pray. The only time, while they were working their fields, was the early morning, when he would gather them after Mass around a bonfire under the ramada for an hour or less. Ibáñez and Gutiérrez did not have to suffer each other's company for long. Father Visitor Bringas decided to banish Florencio Ibáñez to the college. Yet when Ibáñez humbled himself before Bringas at Arizpe, the visitor commuted Fray Florencio's destination to Caborca, where two of the newly arrived interns, Fray Mariano Bordoy and Fray Ángel Alonso de Prado, received him with raised eyebrows, "as if they were saying, 'So this is the mischievous one, the gossiper, the spy of los viejos come to check on our behavior.'" [23] While Ibáñez endured the contempt of tyro missionaries and plotted his return to Sáric, Father Iturralde was having his troubles prying Gutiérrez away from Tumacácori. The presidente had determined to send two interns, Bordoy and Fray Ramón López, to relieve the stubborn and supposedly ailing aragónes. When they reached Tumacácori in mid-February 1796 they presented Gutiérrez with Iturralde's order summoning him to Tubutama. Still he balked. Only two weeks before, Gutiérrez had informed the Father President that his condition was improved, "that only his skin had not yet healed over." Suddenly he was crippled. He wrote asking for permission to travel south to Arizpe for treatment. Iturralde, on Bringas' admonition from Arizpe, denied the request, but three weeks later relented. He had heard from Tubac Commander Errán that poor Gutiérrez was getting worse. If he sat or lay down he could not rise unless someone else helped him up. It seemed only right, reasoned the Father President, to send him a pass to Arizpe where there was a government doctor, "for in the missions there are no other doctors than some old women who are wont by a fluke to hit the mark once in a while." [24] By early May, Iturralde had lost patience. Gutiérrez had not left for Arizpe. In fact, thinking the president's letter contained another summons, he had not even opened it. He was faking. He was saying, reported Father López from Tumacácori, that he would remain sick until Father Bringas departed Sonora for the college, and that then he would manage to stay on at Tumacácori because the western missions were injurious to his health and the others did not suit him. He had prevailed on Lieutenant Errán to appeal in his behalf. According to López, he had Tumacácori and Tubac in an uproar as he mocked his superiors. Now, in answer to the Father President's latest summons, Gutiérrez responded that he could not possibly take the road for Tubutama—he could not even hold the reins of his horse. That did it. Iturralde ordered him by holy obedience, which no friar could refuse without breaking his solemn vows. Even if someone had to ride behind him and hold him on the horse, Gutiérrez was to come to Tubutama instantly. He came. And no one had to hold him on the horse. Once at Tubutama, however, he appeared crippled again. But at times, noted Iturralde, he forgot and straightened up. Soon two Tumacácori Indians arrived to beg "in the name of the entire pueblo" for Gutiérrez' return. The Father President was not fooled.

Back at Tumacácori, Gutiérrez' successors tried to live down his tumultuous legacy, endure a drought, and get along with each other. Fray Mariano Bordoy, of medium build, light complexion, brown eyes, and black hair, came from the island of Mallorca. Born November 30, 1764, in the villa of Felanitx, where the red clay grew good grapes and the windmills provided "a graceful vista," he was not yet sixteen when he left home and took the highway leading west to the city of Palma. There in the historic convento grande de San Francisco, where Father Junípero Serra had studied and taught a generation before, Bordoy was invested with the habit on September 4, 1780. After the novitiate, his vows, three years of philosophy, three of scholastic theology, and ordination, Father Mariano had answered the call to the college of Querétaro [26] Bordoy's compañero at Tumacácori was a city boy born and raised in Madrid, perhaps at court, which apparently he never let anyone forget. Ramón López had studied three years of philosophy and two of theology before he entered the order in Toledo at age nineteen and a half. Still a deacon in 1789, he had joined the mission to Querétaro from the convento in Alcalá de Henares, the famous university town. As he embarked with the others, the port authorities described Fray Ramón as "small, swarthy, black hair and beard, smooth-chinned, blue eyes, the left one somewhat divergent." Thirty years old in 1796, the diminutive, walleyed López was two years Bordoy's junior. [27] When they had been at Tumacácori not quite seven months the two friars received instructions through channels—from the court of Charles IV to Commandant General Nava to the bishop-designate of Sonora, Fray Francisco Rouset de Jesús, to Father President Iturralde—that they take a census of the mission. The Conde de Revillagigedo's 1793 general report on the missions was being updated. For their poor mission they listed 102 names, the marital status of each person, his ethnic or tribal group, and his age. About a third were Pimas; they seemed to be the core of the community, older, more stable, and, like Governor Luis Arriola and Alcalde Francisco Romo, more often the pueblo justicias. As a group the Pápagos, about half the total population, were younger, many of them born of heathen parents, and more likely to flee back to the desert, as Luisa Miranda, thirty, had just done. Under the heading vecindario the friars entered the names of half a dozen families, mostly Yaqui. These, described in the mission books as peones, evidently composed the craftsman-worker corps who supervised and showed the others how. Bordoy added a note. Not since he and López had been at Tumacácori had a single heathen asked to join the community. He had heard that five Pápago families, who had come to work in the mission the previous year, wanted to, but when their leader balked they went away. "Moreover, an Indian told me that when this mission summons Pápagos (for few come of their own will) to come and work, only the men come. They do not bring their women for fear that some will stay. Nevertheless, I have told them that always when they come they are to bring them." From the number of Pima men shown on the census married to Pápago women, their fears were justified. "As for the church structure," Bordoy continued,

In mid-February, 1797, when fellow missionary Bartolomé Socies, like Bordoy a mallorquín, stopped over for a few days at Tumacácori on his way to San Xavier, he found Fathers Mariano and Ramón at odds. They had been getting on each other's nerves. Bordoy enjoyed reasonable health and could eat almost anything. In the opinion of Socies he showed all the signs of becoming a good missionary. He was much involved in teaching the Indians to pray and to sing; and he had the children in school. "When he has gained more experience and knows the Indians and settlers more, he will be better." Poor López, raised at the court of Madrid, had a delicate stomach. He hated the mission food, particularly when he was sick. So he hardly ate, and that made him weak, ill-tempered, and more susceptible to sickness. Father Socies sensed the two friars' incompatibility, but he counseled them to put aside "those trifles." Then he spoke to his paisano in private. Could not Father Mariano improve the mission cooking? As in other missions the cook cooked "from the head, without a book since he does not know how to read, and things never come out the way they are supposed to." Bordoy had tried. He had gone out and hired a gente de razón woman. In one week López had fired her "because she did not please him." The little madrileño wanted to get away from Bordoy. He resented Socies' assignment to San Xavier and told him so. Why did Socies not stay at Tumacácori with his paisano and let him go to San Xavier, López wanted to know. That, Socies told him, was not what the superiors had ordered and for that reason he did not expect to hear any more about it. [29] Ramón López left Tumacácori without regrets on May 29. Father President Iturralde explained why. During the year and three months López had been there he had suffered almost continual fevers. "I believe," wrote Iturralde, "that because the Father is very delicate, raised at court, and the cooks are very gross, he eats with repugnance and his stomach turns over and produces pernicious humors." Iturralde had ordered him to Ati, one of two Pimería Alta missions the presidente considered healthful. But the dark little friar from Madrid did not improve. In October, 1798, his superior moved him to the other "healthful" mission, Caborca. [30] Soon after, Ramón López asked for permission to return to the college. It was granted. He left Caborca in 1800. He had suffered enough. A healthy friar took López' place at Tumacácori, but he too hated the mission. Tall, fair-skinned, with brown hair, brown eyes, and a long face, Fray Angel Alonso de Prado was yet another of the ill-suited interns who came with Father Visitor Bringas. He had been at Caborca. He was older than Bordoy by nearly five years but not as long a Franciscan. A traveler in the nineteenth century would describe Prado's birthplace, the villa of Bentretea in the archdiocese of Burgos, as "forty-three houses of a single story, offering little comfort but solidly built, forming a few dirty and unpaved streets." Most of the men were muleteers. On March 1, 1782, a day past his twenty-third birthday, Ángel Prado had committed himself to the Franciscan novitiate at La Cabrera, thirty miles north of Madrid. Like Ramón López a resident of the convento in Alcalá de Henares in 1789, he too had volunteered for overseas missions. [31] He now knew it had been a mistake. Writing to the Father Guardian of the college on May 30, 1797, after only one week at Tumacácori, Fray Alonso poured out his bitter cup.

He went on to describe the dire state of the mission and to explain some of his dilemmas. He asked that the procurador send to Tumacácori only what was specifically requested on the friars' annual orders, or memorias, nothing extra. Because of the continuing drought, the mission had been reduced to buying food. That year they would harvest only forty of the needed two hundred fanegas of wheat. He and Bordoy would use their spare habits and tunics to bury dead Indians for no one could afford shrouds. Trade had ceased. What money the mission had was "in the possession of good friends." If God continued to withhold the rain, the mission would be done for. Because an unordered canister of snuff had arrived, Prado added ironically, he was fixed for tobacco for two years, if they did not take pity and recall him sooner. Father President Iturralde had made Father Ángel responsible for Tubac. He had written to Bishop Francisco Rouset asking that the faculties of interim chaplain previously conferred on Ramón López be granted to Prado. [33] This sorely exercised the tall, already disquieted grayrobe. Exactly what was his obligation? Was he formally bound as a parish priest or was it merely a matter of charity? "This," he wrote, "is a centipede," a problem with a hundred legs and a bite which only the wisest heads at the college could resolve. The wiles of the Indian women who hung around the presidio scared him. Some friars were actually accepting fees, ten pesos for a marriage and a peso for other services. In conscience he could not reconcile this, even under the most extenuating circumstances, with his vow of poverty.

But everywhere Father Ángel looked he found another "centipede." The dilemmas he described had perplexed Christian missionaries from the time of Saint Paul. He applied them to the Pápagos, many of whom had been baptized—in pueblos since destroyed, or in danger of death, or as children—but who now for one reason or another lived among their heathen relatives. If two of these "Christians" married more gentilico, without benefit of clergy, was the marriage valid? In the case of just ecclesiastical impediment was it valid? Was it valid if the couple were from one of those pueblos formerly in the possession of the king and Church but since laid waste? What about a baptized woman and a heathen man? What about a Christian captive among the Apaches or other heathens who had never acknowledged the Church? In the case of a Pápago who claimed to have been baptized previously, was the friar to take the Indian at his word, or rebaptize him to make sure? Prado thought that many Indians could not be trusted in this regard. In the case of heresy or of formal apostasy among mission Indians, whose responsibility was it to punish them, the friars or the bishop? In closing, Fray Ángel begged again to be withdrawn. "If not, send me two pairs of sandals." [34] When the Father President conducted his official visitation at Tumacácori on September 30, Ángel Prado was still there. He, Bordoy, and Iturralde began the day with Mass in the church at which "most of the Indians" were present. The superior noted that the Fathers preached through an interpreter and that daily one or the other led the neophytes in prayer and examined them in the catechism. After he had heard the Indians of Tumacácori pray in Spanish and Piman, he judged that they knew how "moderately well." He then addressed the Indians alone with a prepared statement in their own language. Was there anything, he asked them, that they wished to report about either of their Fathers? They must not lie, but they need not fear. He would take action if they would but speak up. None did. In conclusion, "I exhorted them to comply with the law of God and with the precepts of the holy Church, to work and go about their business as civilized persons, neat and clean, and that they all obey their justicias and their Fathers,. . ." Evidently Bordoy and Prado had seen to patching up the church. No longer was it "split in two." Iturralde described the structure as very small, with adobe walls and fiat, viga roof, but decent. The adjoining sacristy was well supplied with excellent vestments, properly kept along with the sacred vessels in chests. The Father President inspected holy oils, baptismal font, and books of administration, of baptisms, marriages, burials, and patentes—circulars, orders, statements of compliance, notices of visitas, and other such things. All conformed to Roman ritual. Since the Bringas visitation of 1795, Iturralde counted nine baptisms of mission Indians and two of heathens, three marriages, and twenty-one burials. He put down the population of Tumacácori as sixty-seven, very low, perhaps because he listed only mission Indians, hijos de la misión, or perhaps because the fall influx of Pápagos had not yet taken place. The three missionaries discussed the current economic crisis. Ironically, Iturralde suggested, the missions had been better off in the days of widespread Apache raiding. Many of the mines in the province, prime consumers of mission produce, had played out. Miners had turned to raising crops in competition with the missions. For the same reasons, and because the check imposed by Apache raiding had been largely removed, livestock had multiplied to the point of glutting the market. Both San Xavier del Bac and Cocóspera, whose new churches were nearing completion, owed money to Tumacácori. But the biggest debt was owed by San Ignacio to hacendado José de los Heros. "If this land were as it was before, it would not take long to pay it off or, better said, it would already have been paid." [35] As relations among missionary brothers in Pimería Alta festered, Father President Iturralde sought comfort in Psalm 133: "Behold, how goodly and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!" In 1797, in the wake of Bringas' house cleaning, at least half the friars were unhappy with their assignments or their companeros. The tempestuous Florencio Ibáñez was back at Sáric, newly embroiled in disputes with the Father at Caborca and with Iturralde at Tubutama. Narciso Gutiérrez still resented his removal from Tumacácori and his surveillance by Iturralde. That Easter season Ibáñez ad Gutiérrez had performed their annual spiritual exercises together at Sáric and had emerged allies. Iturralde braced himself. During the months that followed, as notes, gossip, charge, and counter-charge flew back and forth among the mission conventos of Pimería Alta, the fight had become obscene. The Father President, convinced that Gutiérrez and his "confidant, counselor, and confessor" Ibáñez were out to blacken his name and have him removed from the missions, had fought dirt with dirt. When Ibáñez pointed out that the children of Iturralde's cook were suspiciously light skinned, Iturralde countered that the wife of Ibáñez' mayordomo, who had easier access to that friar than his cook had to him, was mother to a similarly fair brood. Furthermore, far fewer improprieties took place in the Tubutama kitchen than among the unsavory bunch of syphilitic boys who hung around Sáric's. On his visitation in September and October, the Father President had sought to pour oil on the troubled waters, at least to reestablish community with the other friars. When he approached his quarters in Tubutama after this five-week absence he could scarcely believe his eyes. There in the anteroom, with the door wide open, lay his compañero Father Narciso "stretched out ... like a Pápago indecently unveiled to the thighs." He made no effort to welcome his superior. He just lay there. Iturralde entered, said good morning, and asked what ailed him. A fever, he had a fever, grunted Gutiérrez. "I told him, 'It is no good here Your Reverence, especially in that position. Pray go to your room and go to bed.'" Without another word Gutiérrez obeyed. "What seemed strange to me," Iturralde wrote later on, "was that he was happier without my company, but afterwards I learned why." [36] Gutiérrez had written to the college, "not out of spite," he claimed, "or for any other such reason, but obliged by my confessors." The principal charge against Iturralde concerned the woman Gertrudis, who while entitled "cook" had "grown fat at the mission's cost." To the scandal of the rest of the people she had amassed large herds of stock, allegedly because of the Father President's patronage. Rumors had spread all over the Pimería. The mayordomo of San Xavier carried them to Tubac. The friars had become the subject of dirty jokes. [37] Early in December, Iturralde answered his accusers in a twenty-page letter to the Father Guardian, enclosing as exhibits more than thirty documents. He charged Ibáñez and Gutiérrez with numerous unbrotherly acts and indiscretions and characterized them as insubordinate gossipmongers. Ibáñez, on whom the Father President vented more of his wrath, was so unstable that when things went against him he frequently talked of hanging himself from a mesquite tree. [38] The college upheld the Father President. When Ibáñez, claiming cruel persecution by Iturralde, begged for the second time to return to Querétaro, the superiors granted his request. After sixteen years in Pimería Alta, he left Sáric in the company of a merchant on August 12, 1798, to all appearances ignominiously finished as a missionary. Yet three years later he landed at the port of Monterey in Alta California, age sixty, ready to renew his career. He had quit the Querétaro college and rejoined San Fernando. For seventeen more years Florencio Ibáñez lived the life of a missionary. Finally he died at Soledad, November 26, 1818, at the age of seventy-eight. In California he is remembered as a musician and the author of nativity plays. [39] Fray Narciso Gutiérrez had evidently made his peace with Iturralde post haste. In January, 1798, just a month after the president's sordid report to the college, Gutiérrez was back at Tumacácori. Ángel Alonso de Prado, whose self-righteous rigidity suited him more for the college than the missions, had departed or was preparing to, causing the Father President to lament the loss of a healthy friar. Back at the college Prado would be elected Father Guardian three times before his death on December 28, 1824. [40] As for Gutiérrez, who shared Tumacácori with Mariano Bordoy during 1798 and 1799, he had come home to stay. The presence of Father Visitor Diego Bringas in the missions of Pimería Alta had stirred up a nest of hornets in habits. After three years of unfraternal strife Father President Iturralde, who suffered physically from a bladder disorder "and many other parasitic pests," [41] had managed to impose order if not harmony, the letter of Psalm 133 if not its spirit. During the last five years of the eighteenth century the Queretaran friars pleaded on all levels, local, provincial, and national, for missionary expansion, and were frustrated consistently. Wars in Europe and threats to the Spanish empire in America reduced the question of salvation for the Pápago Indians to low priority. But the friars conceded nothing. With the visitation of Pimería Alta and his reconnaissance of the Río Gila behind him, Father Bringas had got his notes together, conferred at length with Father Barbastro, and in mid-March of 1796 resumed talks with Commandant General Nava at Chihuahua. In the matter of the Pápago Indians the friar described the success of Fray Juan Bautista Llorens in attracting heathen Pápagos to settle in the pueblos of mission San Xavier. He cited an order of Nava himself to Captain Zúñiga granting the Pápagos of the ranchería of Aquituni certain privileges if they would join the mission visita at Tucson. Early in 1796, suffering from the drought, they had come in with Lieutenant Mariano de Urrea, 134 of them. Fifty-one had been baptized. But there had been trouble. The Hispanic community, soldiers and settlers from the presidio of Tucson across the river, had diverted what water there was to their fields, leaving the Indians hardly a trickle. They had let their thirsty stock trample and browse Indian fields. Bringas appealed to the commandant general to enforce the land and water regulations for presidio and pueblo and recompense the injured parties; to provide the newly arrived heathens with oxen and tools; to reimburse Father Llorens for the food and clothing he had given them; and to authorize a second sínodo for San Xavier. On the recommendation of his legal adviser, Asesor Pedro Galindo Navarro, the commandant general turned down the friar flatly. [42] The Pápagos of Aquituni meanwhile fled back to the desert, "perhaps," observed Father President Iturralde, "because of the perverse counsel of the old Christians." Father Llorens went after them and persuaded them to return. But when Captain Zúñiga reported the affair to Nava, the commandant general decreed that no more heathens be added to mission San Xavier del Bac, a shocking and unchristian measure in the eyes of the missionaries. Father Bringas had all but promised the Gila Pimas the benefit of missions. Despite all his evidence of their desire for baptism, their industry, and their loyalty, he could wring no commitment from Commandant General Nava. It was incredible, lamented Father Iturralde, that in a hundred years the Spanish frontier had not expanded one step toward the Gila. The Gileños were more than willing, friars were available—only the government stood in the way. [43] Everything Bringas proposed Nava and Galindo Navarro quashed. Back in Querétaro after a year in the field, the friar presented himself before the guardian and discretory empty-handed. There was nothing left but a direct appeal to the king. "Without a commandant general who is zealous for the honor of God and king," proclaimed the semi-retired Father Barbastro from Aconchi, "neither the missionaries nor the bishop can accomplish a thing." [44] Bringas argued the college's case in a long, heavily documented representation to the crown finally submitted in 1797. The Queretaran archivist labeled the file copy "Report to the king concerning the missions of Pimería Alta, new foundations, the perverse measures of the [General] Command, the ill-founded peace with the Apaches, and many other important matters." If His Majesty would but approve the several proposals contained therein, three important benefits would result: 1) the spiritual well-being of non-Indians along the entire west coast from Jalisco to the presidio of Tucson, 2) continued propagation of the Faith in the eight Indian missions of Pimería Alta, and 3) the conversion of more than 25,000 heathens. To prove that the Pimería Alta missions had not gone stale, that they deserved continued royal support as conversiones vivas, Bringas appended lists of nearly a thousand heathens, of a dozen different tribes, baptized in these missions since 1768. He reiterated the settling of the Pápagos of Aquituni at Tucson and the Gila Pimas' exuberant desire for missions. Carefully demonstrating how royal expenditures might be kept to a minimum, he proposed the founding of six new missions, two each for the Pápagos, Gila Pimas, and Cocomaricopas; two new Indian presidios; and Queretaran hospices at Sinaloa and Pitic, the first to support far-ranging home missions, the second for Indian missions. Again he asked for two missionaries permission and more friars from Spain, resurrecting all the arguments of the 1770s. And finally the friar pleaded for the love of God that Pimería Alta be detached from the Provincias Internas, like Alta California, and restored to the viceroy's rule. [45] While Bringas' report to the king was held up in the mails by a British naval blockade, the king approved Commandant General Nava's "measures for good government," including civilian management of mission economics. Nava sent a copy of the cedula to Father President Iturralde in November, 1797, with instructions for converting the missions into "doctrinas." The Queretaran friars would be relegated to a spiritual ministry only and supported by Indian tribute. All this they had heard before. [46] "The good government they propose," Iturralde wrote to the college, experience has shown clearly is that under which churches crumble, the communal properties are exhausted, and the Indians are oppressed without relief." Bringas had written pages and pages to the king, citing laws and precedents, to show why the pueblos of the active Pimería Alta frontier must remain traditional missions, subject in everything to their missionaries. He had detailed the ruin of the Yaqui and Mayo pueblos under the doctrina system and predicted the same fate for Pimería Alta if Nava's orders were allowed to stand. [47] More bad news almost made the Father President laugh. Now Intendant-Governor Alejo García Conde was demanding that the Queretaran friars pay the tithe on mission produce. In response Iturralde wrote to Barbastro and asked the dean of the missionaries to go over to Arizpe and reason with the intendant-governor. The missions of Pimería Alta had always been exempt from paying the tithe. [48] Although the friars went about their ministry in Pimería Alta as they had for the past thirty years, the shadow of the general command hung over them like a heavy desert thunderhead. Much of the blame they laid to Asesor Pedro Galindo Navarro. They never had forgiven him for designing Croix's bastard Yuma settlements eighteen years before. This official, in Iturralde's words, "is not only anti-friar but also Antichrist since he opposes new missions contrary to what the king has ordered in the laws of the Indies. As long as he remains, we can hope for nothing favorable." [49] By November, 1798, Iturralde had all but given up hope. "In these provinces things are so critical with regard to the faith that it appears headed for nothing short of total subversion." [50] He was wrong. Together he and Barbastro brought Intendant-Governor García Conde, "a good man and of good intentions," around to their way of thinking on the tithe. Commandant General Nava, more concerned with matters of defense, did not press his proposal to make the missions of Pimería Alta into doctrinas. But neither did he offer the friars the least support for expansion of their missions to the Gila. At Tumacácori, Narciso Gutiérrez had resolved to build a proper church. In his favor he would have the Apache "peace," such as it was, and a decade of relative prosperity; against him Napoleon in Europe and unrest in New Spain. He lost Mariano Bordoy in 1799. Evidently the brown-eyed mallorquin was not as tough as he thought he was. In January, Father President Iturralde had seconded Bordoy's request for retirement to the college. He did not leave Tumacácori until after the summer, and then he did not retire. Somewhat restored, he decided to stay on in Sonora. Between 1802 and 1805 he served as compañero at Aconchi, where the grand old man Barbastro had died on June 22, 1800. By 1806 Bordoy was back in Pimería Alta, assisting at Tubutama. When finally he did return to the college his health was broken. Until his death on October 6, 1819, at the age of fifty-four, he did what he could around the college, playing the organ and hearing confessions. [51] Narciso Gutiérrez had no illusions about the Apache peace. What kind of a peace was it, Father Visitor Bringas had asked, that allowed a partially conquered enemy to retain his freedom of movement, his weapons, his Christian captives, his thieving ways, and his polygamy, all the while feeding his belly at government expense? The Apaches mansos, the tame ones, who lined up outside the walls at Tucson and several other presidios to claim their weekly rations of maize, meat, tobacco, and sweets, had become another source of friction between the Queretaran friars and the commandant general. Only half-hearted measures had been taken for their spiritual welfare. Their pagan vices had been tolerated and malevolent Christians had bequeathed some of their own—an integral part of the Bernardo de Gálvez policy—gambling, dancing, swearing, concubinage, and the like. When the friars suggested subjecting these Apaches to a mission-like environment, Pedro de Nava had ignored them. [52] At best the Apache peace was a relative thing, at worst a sham. When it suited their purposes to raid and kill, some of them still did, as at Tumacácori one hot Friday, June 5, 1801. Three men died. They had been tending the flocks: Juan Antonio Crespo, forty to fifty years old, a Pima raised at Caborca, husband of María Gertrudis Brixio listed variously as a Yaqui or an Ópata, and father of three young children; José María Pajarito, twenty; and Félix Hurtado, fifteen. Their bodies lay outside the wall. The people inside knew it but they could do nothing. How many Apaches there were no one dared say. This was no hit-and-run raid for stock. The Apaches were still out there, waiting, hoping to draw the people into the open. They stayed all night and were there next morning. Finally, Saturday afternoon all the settlers and Pima troops from Tubac who could be rounded up during the two days arrived to relieve the mission. The Apaches withdrew. Only then could the bodies be brought in for burial and the damage assessed. The attackers had wantonly slaughtered "more than 1360 sheep." [53] After two fatiguing three-year terms as Father President, the unwell Francisco Iturralde resigned in 1801. He finished out the year at Tubutama then quit Pimería Alta, a twenty-five-year veteran. The college chose Iturralde's steady, non-controversial neighbor at Oquitoa, Fray Francisco Moyano, to succeed him as presidente. The well-built Moyano, with black hair, dark brown eyes, and a mole high up on his left cheek, had come to Sonora in 1783 in the train of Bishop Antonio de los Reyes. After the custody folded he affiliated himself with the college of Querétaro and stayed on in Pimería Alta. He spoke Piman well. In the tradition of Barbastro and Iturralde, Moyano would serve as Father President as long as he was able, over sixteen years. [54] Toward the end he would suffer even more grievous dissent than they had. About the time Iturralde handed the papers and the headaches of the presidency to Moyano, Bishop Rouset again asked for headcounts in the missions. At Tumacácori Narciso Gutiérrez complied on December 9, 1801, enrolling each person and noting his ethnic or tribal designation, his age, and his marital status. Heading the list was Juan Legarra, a thirty-three-year-old Pápago evidently picked as governor after the death of Luis Arriola in May, 1799. Since the census by Mariano Bordoy five years earlier, the mission's total population had increased by only five persons, from 102 to 107. But the composition had changed. The ratio of non-Indians to Indians was ascending; at the end of 1801 it stood at better than one to four. On the 1801 census Gutiérrez typed some of the Indians earlier designated Pimas as Pápagos and vice versa. Like Bordoy, he assigned the father's tribal affiliation to the children, except in the case of Pápago couples, whose children he made Pimas. He split the 1801 census somewhat differently, listing sixty-eight mission Indians, largely Pimas and Pápagos, and thirty-nine peones y agregados. The distinction, it appears, stemmed from who was and who was not entitled by membership in the community to a share of the mission's common produce. The peones, or laborers, half a dozen gente de razón families, who seemed to have replaced the Yaquis of five years earlier, were paid, likely in goods and produce rather than cash. The agregados, a few Yuma converts recently settled at Tumacácori, apparently got their keep as potential members of the mission commune. [55] When he drew up his first state-of-the-missions report in May, 1803, Father President Moyano could point to half a dozen new, brick and mortar churches built under Franciscan supervision. Most of the others had been repaired and renovated. Only two churches in all Pimería Alta did he judge substandard, those of Caborca and Tumacácori. At Caborca, Fray Andrés Sánchez was about to begin construction. At Tumacácori a church was in Moyano's words "currently being built anew." Father Narciso had already begun. Like Sánchez of Caborca, Gutiérrez took the magnificent Velderrain Llorens structure at San Xavier del Bac, built at a cost of over 30,000 pesos, as his model and his goal. Unfortunate for him, circumstances would impose a whole series of retrenchments. Perhaps he was too optimistic. He staked out the foundations some fifty feet behind the narrow little Jesuit church. The new church would be oriented north-south, and it would have the adjoining convento to the east, as at San Xavier. It would measure some one hundred feet long outside, nearly twice the length of the old church. In 1802 Father Narciso had brought in additional laborers and craftsmen. Moyano's figures for that year credit Tumacácori with a population increase of 70 percent over 1801—76 Indians and 102 "Spaniards and persons of other castes." [56] The problem for Gutiérrez now became one of economics: how to sustain a long-term construction project with no more resources than his poor pueblo could muster. He could try to raise surplus wheat, but that depended on the weather. The mission did have livestock, more than ever before. But prices had fallen off sharply. Cattle that sold just five years earlier for ten pesos a head, now brought only three and a half. The intendant-governor of the province, don Alejo García Conde, feared the price might soon drop to a peso. [57] As Father Moyano pointed out, the only industry in the missions, aside from pottery and basketry, was the weaving of blankets and sarapes from the wool of mission sheep. But unfortunately, Tumacácori's flocks had been nearly wiped out in the Apache raid of June, 1801. Because these raiders often came by way of the mission's deserted visita of Sonoita, Moyano, probably at Gutiérrez' suggestion, urged reoccupation of the site and a strong enough guard to hold it. [58] But that came to nothing. None of the friars was saddened by the news late in 1802 that Commandant General Pedro de Nava had finally stepped down. In their eyes his successor, Brigadier Nemesio Salcedo y Salcedo, could be no worse. Though he showed more interest in the missions of the Sierra Madre, closer to his capital of Chihuahua, when the time came Salcedo would support the Queretarans' bid for more religious from Spain. Fortunately, too, the first years of Salcedo's command coincided with an economic resurgence in Sonora. Mining picked up. The new commandant reported an October, 1803, strike at Noriega, not far from Altar. New placers came into production at Cieneguilla, and despite drastic fluctuations caused by too much or too little rain, epidemics, and the searing heat, the motley population had risen to 5,000 by early 1806. The intendant-governor, García Conde, talked of opening new ports along the Sonora coast. Already some merchants had begun exporting grain and hides and tallow in small schooners and sloops. [59] In the middle Santa Cruz Valley the new prosperity was evident but limited. Stock wearing the Tumacácori brand grazed the hills for twenty miles along the river, from south of Guevavi. Travelers on the valley road noticed the massive foundations of Father Narciso's church, great river boulders set in mud mortar. At Tubac senior Ensign Manuel de León, who had taken provisional command of the garrison on the death of Lieutenant Nicolas de la Errán, estimated the presidio's cattle herd at a thousand head in the summer of 1804. Down the road forty-five miles north at Tucson, Captain José de Zúñiga reported 4,000 cattle, from which the Apaches mansos were being fed, 2,600 sheep, and 1,200 horses. As industries he included cotton growing and weaving and a lime deposit being worked north of the presidio. Hides from Tucson were being sold as far south as Arizpe. [60] Still, Tumacácori was poor. Once Fray Andrés Sánchez began building at Caborca, Father Narciso could not keep up. His project lagged. When the Father President made out his second state-of-the-missions report in February, 1805, he described Tumacácori's old church as "very deteriorated and narrow." Construction of a new one had begun, but he mentioned no progress since the last report. In contrast, at Caborca Father Sánchez had the walls up and already had begun the barrel-vault roof. Tumacácori's total population—82 Indians and 82 Spaniards and other castes—was down and Caborca's up from two years before. Interestingly, Tumacácori had lost twenty Spaniards and persons of other castes while Caborca had gained thirty, an indication of how the two jobs were going. The Apaches were partly to blame. Father Moyano explained:

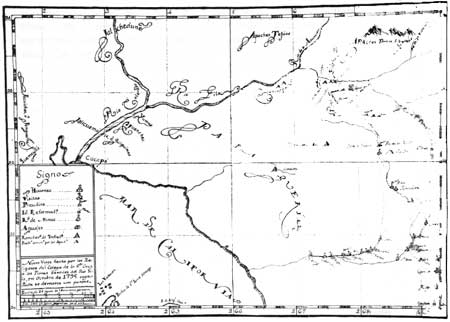

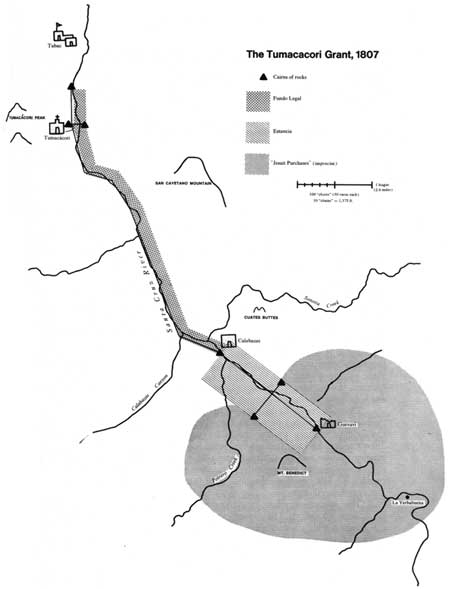

These and other outrages kept the missions of the north and east poorer than the others, retarding the growth of their herds and the activities of their people. A garrisoned settlement on the Gila would help, thought Moyano. That would have pleased Francisco Garcés. [61] For five years Father Narciso had managed pretty much on his own doing double duty as missionary and chaplain. [62] Between 1804 and 1807 Father President Moyano sent him in rapid succession three eager but luckless compañeros. Tall, thin-faced, with black hair and blue eyes, Fray Manuel Fernández Saravia was from Pola de Lena, some twenty miles south of Oviedo in Asturias. He had sailed with the smaller first wave of the 1789 mission aboard the frigate San Juan Nepomuceno. At the college he was literally struck dumb. As his superior had noted in late 1795, Fernández Saravia was "unable to practice the ministry because he is totally without a voice." Evidently he had recovered enough to set out for the missions in 1802. He had been working at Caborca with Father Sánchez. On February 19, 1804, the forty-one-year-old Fray Manuel baptized a newborn child at Tumacácori. But he did not last. Soon after mid-June, 1804, he transferred to Sáric where he died of a seizure on November 11, unable to receive viaticum. [63] Whether on business or sick leave, Gutiérrez was away from his mission during the winter of 1804-1805, between November and the following May. A devout but sickly thirty-four-year-old Mexican, who had been with Llorens at San Xavier since the summer of 1802, rode down to Tumacácori to fill in. Fray Joseph Ignacio Ramírez de Arellano, from an old family of Puebla de los Ángeles, had been invested with the Franciscan habit only six years before, on December 11, 1798, at the college. He had been a grammar and philosophy teacher at the Colegio Carolino in Puebla before that. A mature adult, he really wanted to be a Franciscan. Writing home to his mother, he described his investiture as "a ceremony which would have caused a rock to melt. By the embrace of all the fathers, I became a brother of them all. Just think what that means, to be a brother of so many. I look forward to being a servant to them." From San Xavier, Ramírez had continued writing to his mother and to a brother, Joaquin Carlos. He told of the variety of fruit in the mission garden, his heat rash, the frightful storms and winter cold, and the medicinal qualities of the jojoba. He told of the friars' frustrations. "The neglect on the part of the government, if not the calculated disregard, to work for any advance here, stupifies us." Father President Moyano had gone to Arizpe to plead with Intendant-Governor García Conde. The Gila Pimas still begged for Fathers and baptism. Ramírez had probably worried his mother with his exaggerated account of the savage Apaches. "They go about the whole area robbing and killing to get what they can," he had written. "They have nothing else to do or nothing else to think of, nor are the many presidios located here for that reason only, of any avail to restrain them." [64] Apparently at Tumacácori Ramírez was too busy to write. When Gutiérrez returned in May his haggard replacement was battling what may have been an epidemic. In a space of ten days he had buried seven persons, four of them small children. A week later Father Narciso interred a thirty-year-old Pápago he said died of "the green vomits." Ramírez rode back to San Xavier. The next letters his mother received came from Father Llorens. On September 6, the very day Father President Moyano wrote the college asking that Ramírez be recalled because of "his habitual illness," Father Joseph Ignacio was seized by a fever. It kept mounting, and on September 26, 1805, he died, attended by what the friars interpreted as a sign from Heaven. That night as the body lay in the cavernous church illuminated by flickering candles, those who kept the vigil noticed that the dead friar's face and tonsure glistened. They were moist. He was sweating. A healthy color had replaced the grayness of death, and "a most sweet and delightful odor" seemed to come from the body. Yet he was plainly dead. Father Llorens conferred with the two other religious who planned to assist at the funeral next day, apparently Gutiérrez and Fray Pedro de Arriquibar, since 1795 chaplain at Tucson. They would not bury the body as long as the miraculous phenomenon persisted, for "without doubt God wants to manifest by this means the glory His servant is enjoying." Word had spread to the presidio of Tucson and people flocked out to the mission. Hours later the sweating and the odor ceased. Only then did his brethren lay Father Joseph Ignacio to rest. [65] His third compañero in two years joined Gutiérrez late in 1805. Another Mexican, from the Franciscan province of Yucatan, Gregorio Ruiz had affiliated himself with the college on December 20, 1800, and had evidently come to the frontier with the now deceased Fernández Saravia and Ramírez. He stayed longer than the others had, through 1806 and most of 1807. He would serve later at San Xavier and die there on January 25, 1817. Gutiérrez in fact would be called from Tumacácori to attend him, but would reach his side too late, only to learn that "his death had been violent." Meanwhile a Pima died at Tumacácori without the sacraments because of Father Narciso's absence. [66] With some misgivings, Narciso Gutiérrez had watched the new settlers arriving in the valley. Tumacácori's herds, despite sporadic Apache raids, had been increasing "daily." The friar foresaw trouble over land. The poor squatters did not bother him, so long as they recognized that the land belonged to the mission—it was the ambitious potential ranchero who might file a claim on allegedly vacant lands or lands with imperfect title. The legal process was known as the denuncia. [67] Any day it could be used against the mission, particularly to the south where, if one chose to ignore mission livestock, Calabazas and Guevavi had been "abandoned" far longer than the three full and consecutive years stipulated by law. Worse, the mission possessed no legal instrument whatever setting forth its title or its boundaries. With all this in mind, Father Narciso summoned Governor Juan Legarra and the other justicias late in 1806 and suggested to them that they petition for a formal regrant of mission lands. The mission may never have held a specific, all-inclusive title to its lands. As an Indian community it was entitled by statute to all the land its people used. Because the mission existed on a semi-arid and hostile frontier, competition requiring formal adjudication between Indian and non-Indian had been less intense than in some areas. When he compiled his 1793 report on the missions of New Spain, the Conde de Revillagigedo could find no evidence that the Jesuits of harsh Baja California had ever felt the need to define legally the boundaries between their missions. In Sonora, according to Revillagigedo, the blackrobes had "augmented their [mission] properties with grants of land, which they registered and took possession of with royal titles, for the purpose of establishing stock ranches." [68] The Jesuits had indeed bought additional land south of Guevavi. There had been papers. Then too, back when Juan de Pineda was governor of Sonora (1763-1770), it had been agreed that whatever mission land the presidio of Tubac occupied to the north, the mission could make up to the south. All this, Gutiérrez told them, must be made legal and binding. Governor Juan Legarra, a Pápago in his late thirties, headed the delegation to Arizpe. Four more of Tumacácori's principales accompanied him: Felipe Mendoza, a Pima, about fifty-three; José Domingo Arriola, Pima, twenty-seven; Ramón Pamplona, the son of a Pápago father and a Yaqui mother but listed by Gutiérrez as a Pima, twenty; and Javier Ignacio Medina, Pima, not quite fifteen and recently married to one of Pamplona's cousins. [69] Presumably Father Narciso, leaving the mission in the charge of Gregorio Ruiz, went with them. In the capital he arranged for an attorney, don Ignacio Díaz del Carpio, to draw up and duly present to the intendant-governor the Indians' plea. Naming the five principales as representatives of the entire community, Díaz del Carpio proceeded to the reason for their petition. "Inasmuch as the original instruments relative to its former allotment of lands have all been lost, the terms under which it was made at that time are entirely unknown and as a consequence its legitimate and true holdings and boundaries are also unknown." They asked for a fundo legal, a standard township of four leagues, measured in the directions that afforded them the best agricultural lands, and an estancia, or stock range, to include the old cabecera of Guevavi, where Legarra claimed to have been born, as well as the mouth of Potrero Creek. They implored the intendant-governor to do the king's will, always favorable toward "his loyal vassals the poor Indians, especially those like us who find ourselves in abject misery and in a country beset by barbarous enemies." On December 17, 1806, Intendant-Governor García Conde responded favorably to the Tumacácori Indians' petition. He ordered the acting commandant and civil magistrate of Tubac, don Manuel de León, to survey the appropriate lands. As soon as León had three or four days he could devote to the commission without neglecting his military duties, he was to measure for said Indians "one league in each direction, or the four wherever it best suits them, of the best and most useful lands adjoining their pueblo, without prejudice to third parties." León should also measure an estancia of at most two sitios de ganado mayor, cattle ranges of one league each. [70] These were not square but linear leagues, measured from a central point outward in the four directions. The total length of the four measurements added up to the number of leagues allotted. If a pueblo did indeed take for its fundo legal one linear league in each direction, which in the arid north was rare, the area came to four square leagues. More often a pueblo took more in the direction that best served it, three and a half along a river for example, and the remainder on each side. While the total area was far less, the pueblo gained more of the watered river bottom. Tumacácori's six leagues, if squared, would have amounted to more than forty square miles, or 26,029.2 acres, most of them of little use. But instead when the four linear leagues for the fundo and the two for the estancia were laid out on the ground by Ensign León, the mission would claim only a fraction of that area, only about 6,770 acres. One thing bothered Father Narciso, the extreme southern reach of the mission, twenty miles away in the fertile San Luis Valley. He knew that the Jesuits had bought land in that direction with mission funds. He wanted to make certain that the Tumacácori grant included all of these purchase lands, in addition to fundo and estancia. On December 23, 1806, the friar drew up another petition, from the Indians of Tumacácori to Tubac Commandant León, the appointed surveyor. In it Juan Legarra, representing the entire community, begged that sworn testimony be taken from old residents of the area to establish: 1) that the mission's southern boundary beyond Guevavi extended as far as "the rancho of the Romeros," the old Buenavista ranch; 2) that the boundary markers still existed beyond the place known as La Yerbabuena, where there was an old corral belonging to the mission, and in the direction of the Potrero at the far end of the ciénaga grande; and 3) that the documents concerning these mission purchases, once in the possession of the civil magistrate of that jurisdiction, had been lost. The Indians had not pressed their claim to these lands arlier because they did not need them. Now, with increasing herds, they did. [71] Admitting the petition, León called the first witness on Christmas Eve. Juan Nepomuceno Apodaca, a settler of the presidio of Santa Cruz, seventy years old, illiterate, and an heir to the Buenavista ranch, testified that the boundary markers separating Tumacácori's lands and those of the ranch did indeed still exist beyond La Yerbabuena. In the direction of the Potrero he swore the mission's markers were placed above the ciénaga grande, and to the east in the cajón de Sonoita on a very flat mesa. Asked where he had obtained this information, Apodaca said he had observed mission roundups and had talked to the former missionaries (the Jesuits) and to now-deceased magistrate Manuel Fernández de la Carrera. The latter had told him that if anyone was in doubt about land ownership in the area, either the mission's or those of other claimants, the Romeros, the rancho of Santa Barbara, or anyone else, to come to his house where he had the documents. But when he left he took the documents with him. [72] León heard the next witness on January 7, 1807. He was Sergeant Juan Bautista Romero of the Tucson garrison, currently stationed at Tubac as paymaster. Son of the deceased don Nicolás Romero, who owned the Buenavista ranch, he told how as a child his father had taken him out and taught him where their property bounded the mission's. The rest of Romero's testimony corroborated Apodaca's. A third and final witness, eighty-year-old, illiterate Pedro Baes of Tucson, testified on January 9. He had grown up on the Buenavista ranch. He added a few details. Though the mission's landmarks beyond La Yerbabuena still existed, they were fallen down. Traces of the mission's corral, where the Romeros used to come at roundup time to cut out their stock, could still be seen on the boundaries of La Yerbabuena." Baes had raised the boy Eugenio, who had since served as a corporal at Tucson. The lad had used the land titles to practice his reading. Baes added that mission land extended in the direction of the Potrero as far as "El Pajarito" above the ciénaga grande. [73] The proceedings came to three folios, which Commandant León turned over to the Indians. With that matter out of the way, he could get on with the survey of fundo and estancia. The party gathered at Tumacácori on Monday, January 13. León, attended by his two corroborating witnesses Toribio de Otero and Juan Nepomuceno González, formally announced to Governor Juan Legarra and the other Tumacácori Indians present that he would proceed immediately. They assented. Then as a matter of course León asked any adjoining landowners to step forward. Informed by several long-time Tubac residents that there were none in any direction, save the presidio one league north, he moved on to the naming and swearing in of his survey crew. Lorenzo Berdugo, thirty-eight, listed with his family in the 1801 Tumacácori census among mission gente de razón but now living in Tubac, Ensign León named tallyman (contador). José Miguel Sotomayor and Juan Esteban Romero, both of Tubac, would serve as chainmen (medidores); with León Osorio of Tubac and Ramón Ríos, thirty-three-year-old gente de razón resident of the mission, as recorders (apuntadores). All swore to perform their duties "well, faithfully, and legally, without deceit, fraud, or malice." Only Sotomayor could sign. Next day in the early morning cold they began their task in the mission cemetery. Ensign León had asked the Indians to designate the center point from which to begin measuring the fundo legal. Because former Governor Pineda had ruled that they could make up in the south what they were short to the north, they pointed to the cross in the cemetery. With everyone looking on, Leon asked tallyman Berdugo to measure with a legal vara stick (33 inches) fifty varas on a "well twisted and waxed sisal cord," which the commandant had brought along for the purpose. With a wooden handle at each end this would serve as the "chain," fifty varas, or one-hundredth of a league in length. They would chain from the center in all four directions, forming in effect a great irregular cross. They would not bother to run out and mark the corners of the claim. Positioning himself at the cemetery cross with his compass, León sighted north down the valley. Then with his entire entourage, plus five armed men as an escort, the ensign began the survey. The two chainmen on horseback rode one behind the other with the chain strung out between them. When a recorder marked the position of the lead chainman and the tallyman increased his count, the chain was moved up till the rear chainman reached the recorder. Others helped straighten the chain. The second recorder and the tallyman had by then moved ahead to mark and record the next chain. Fifty chains, or half a league, they measured north down the valley, pulling up at "the eminence (divisadero) between the trail to the river flat and two very thick cottonwoods that stand outside the river bed." Because they had reached at that point—in the present-day village of Carmen—the southern boundary of the presidio, León ordered a cairn made, and the party rode back to the cemetery. Now by the same process they measured 332 chains south up the valley, working with the dark, craggy Sierra de Tumacácori on their right and tan, hump-shouldered San Cayetano to the left. That brought them to "the upper side, adjoining the cañada near the place called Calabazas," south of the confluence of Sonoita Creek and the river, which was really stretching it. Placing another pile of rocks there, they rode back again to Tumacácori.