Contents Foreword Preface Jesuit Foundations Gray Robes for Black 1767-68 The Archreformer Backs Down 1768-72 Tumacácori or Troy? 1772-74 The Course of Empire 1774-76 The Promise and Default of the Provincias Internas 1776-81 The Challenge of a Reforming Bishop 1781-95 A Quarrel Among Friars 1795-1808 "Corruption Has Come Among Us" 1808-20 A Trampled Guarantee 1820-28 Hanging On 1828-56 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

EARLY IN JANUARY, 1768, while the friars bound for Sonora still bided their time in Tepic, Father Guardian Romualdo Cartagena had led a small delegation of their brethren from the college of Querétaro four or five blocks downtown to the massive gray Convento de San Francisco to see a man about replacements. They had an appointment with Fray Manuel de Nájera, the order's commissary general for New Spain. Nájera, at the insistence of José de Gálvez and the Marqués de Croix, had planned the substitute Franciscan ministry to the Jesuit northwest. In terms of manpower, expelling the Jesuits from New Spain all but depleted the Franciscans. Suddenly called upon to provide scores of missionaries, the friars had hurried every available man into the field. Spokesmen for the missionary colleges, where only the aged and infirm were left rattling about, begged for reinforcements from Spain. Because of the distance and the slow-moving government bureaucracy, the process took years. Father Nájera agreed that the college of Querétaro should apply to the viceroy for permission to send forty-eight-year-old Juan Domingo Arricivita, a Mexican-born veteran of the Texas missions, to Spain as a recruiter. Six weeks later the Marqués de Croix wrote to the minister of the Indies in the college's behalf, just as he had done several months earlier for the college of San Fernando in Mexico City. In June the Council of the Indies, sitting in Madrid, approved, and Arricivita, having secured the clearance of the Inquisition to take along his servant Gregorio de Acosta, boarded a ship at Veracruz. At the court of Madrid in October the native of Toluca formally petitioned the king for authority to recruit, equip, and transport to Querétaro at royal expense a mission of forty friars. In October the matter was taken up routinely by the Council of the Indies and submitted for an opinion to the fiscal, or crown attorney. The fiscal found several things wrong. First, Arricivita had failed to stipulate how many of the forty were to be priests. Furthermore, Law I, Title 14, Book I of the Recopilación de Indias required recruiters to document the need for missionary recruits with reports from the viceroy, the audiencia or governor of the district, and the local bishop. Fray Juan had nothing from the audiencia of Guadalajara, the archbishop of Mexico, or the bishop of Durango. In Arricivita's case the fiscal recognized certain extenuating circumstances. The college had only recently taken on the burden of the Sonora missions, sending its last fifteen able-bodied friars to the frontier. More were needed. "Canon and royal law, as well as the constitutions of the Franciscan order," required that the friars not live alone. In Sonora where a missionary could get lost or killed between mission pueblos, this rule took on added urgency. When a friar fell ill he should have a companion to nurse him and to prevent his neophytes from backsliding. Though the Council chose to overlook the irregularities this time, it admonished the Franciscan commissary general of the Indies. Henceforth, recruiters would be expected to comply with the law. The royal order authorizing forty Franciscan priests for the Querétaro college, dated November 7, 1768, was three weeks old by the time it reached Arricivita. The friar began recruiting at once. Two and a half months later, on February 20, 1769, he again made application to the king. Even though he had "sent out into the provinces the licenses or summons to awaken the religious such a momentous opportunity," he had succeeded in getting commitments from only twenty suitable priests. Spain, it seemed, was overrun by recruiters from America. If he could enlist seminarians, subdeacons and deacons who had completed or nearly completed their studies, and a lay brother or two, Arricivita knew he could fill his quota. Not only would the younger men pick up Indian languages more readily and respond more favorably to discipline, but they could serve longer. Although the request circulated only within the court at Madrid, favorable action on it required a month—from the king to Minister of the Indies Julián de Arriaga, to the Council, to the fiscal, and then back up the line. By June, 1769, Fray Juan had his forty. The list he submitted for approval included thirty-two priests, six deacons and subdeacons, and two lay brothers. They had already assembled in a rented house at Puerto de Santa María just across the bay from Cádiz. Since no further irregularities showed up, Arricivita could now prepare to sail. [1] That took five months. Certification of travel expenses, per diem, supplies; clearance from the Inquisition; booking passage and compiling the passenger lists—there were a thousand details. All the while Fray Juan tried to maintain harmony in a group of forty impatient men. Had they been permitted to talk to the ex-Jesuit missionaries from Sonora being held under house arrest in the same town, the friars' months of waiting might have been more productively spent. A few of them sickened and had second thoughts. Eventually thirty-eight sailed. Their ship, the San Francisco de Paula alias Matamoros, a brand new seventy-four-gun man-of-war constructed in Havana, stood out to sea November 25, 1769. After ninety-five interminable days, including a howling storm within sight of shore, she raised tropical, pestilence-ridden Veracruz. [2] One friar died there. The others traveled up to Mexico City and then northwest to Querétaro where they were welcomed April 4, 1770, on the feast of Saint Isidore of Seville. Fray Juan Domingo Arricivita, best known to history as the chronicler of the college, was exhausted. The mission of 1769 proved a disappointment. After only six months, five of the priests petitioned the Father Guardian to release them. They simply could not, they said, "endure or conform to the regular and rigid life led in this college both day and night." They were willing to be scattered about the provinces and to suffer punishment for having left a missionary college before their ten years expired. To keep peace in the community, the discretory sorrow fully let them go. The following year, 1771, one priest died. Another was disaffiliated when a doctor testified that he would go out of his mind if he stayed, as was one of the lay brothers who claimed to be "utterly depressed." [3]

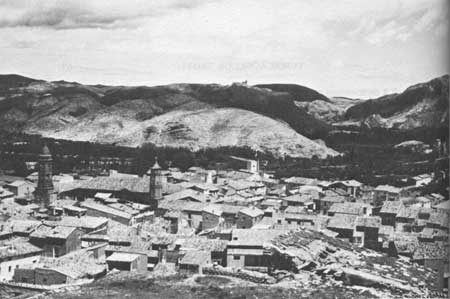

Twenty-nine members of the mission of 1769 stayed. In mid-1772 fourteen still resided at the college, nine were in the missions of Sonora, and six in the Coahuila and Texas establishments. [4] Over the years eight of them would serve at Tumacácori. [5] Francisco Sánchez Zúñiga who had substituted for Fray Juan Gil in the summer of 1771 was the first. The second, a swarthy thirty-year-old of average height with a mole on his cheek, arrived a year later. [6] During those first muggy hot days when the sweat ran down his face and the gnats got in his eyes and ears, Fray Bartolomé Ximeno may have remembered the summer breeze in the hills south of Zaragoza, those hills dotted with pin and turkey oak and full of the smell of Spanish broom, furze, and rosemary. His village, Santa Cruz de Tobed on the Río Grio, was nothing to boast about, just a poor farming community described by a later traveler as composed of "fifty ill-constructed houses." The climate was somewhat cold but healthful. Still, some of the residents "suffered pneumonia and intermittent fevers." [7] Even if Ximeno was not of a nostalgic bent, his reunion with Father Garcés in the summer of 1772 probably set the two grayrobes reminiscing. Morata del Conde, Garcés' hometown, lay no more than a short morning's walk from Ximeno's. As teenagers both of them, Garcés in 1754 and Ximeno five years later, had entered the Franciscan order at the same place, the castle-like convento of San Cristóbal de Alpartir. They had met in the city of Calatayud: while Garcés studied theology, Ximeno made his novitiate. [8] Now eight thousand miles from home the two sons of Aragón were neighbors once again. While Bartolomé Ximeno took the measure of the Pimas and Pápagos of Tumacácori for himself, Fray Antonio María de los Reyes in Mexico City wound up an eighty-two-page description of the Sonora missions. Reyes, like former Father President Buena, disparaged these Indians of Pimería Alta. "They are," he wrote,

From their correspondence it is obvious that the friars held a variety of opinions about their native charges. Almost all viewed the mission Indians as children. The missionary, said Father Guardian Cartagena, must have all the qualities of the paterfamilias: solicitude, affability, firmness. Some of them, like Buena, seemed to doubt their children's capacity to grow, to achieve cultural and spiritual maturity, considering the Indian almost less than human. Their feelings manifested themselves in various ways, such as a reluctance to administer to Indians the sacrament of the Eucharist. Other friars, like Francisco Garcés, saw Indians as earthy and deprived, but human and capable. Fray Francisco Antonio Barbastro, soon to arrive on the Sonora frontier, would become a champion of Indian aptitude. If they did not learn, it was not their fault, he maintained, but their teachers'. They possessed, in his opinion, "at least as much talent, I would say more, than these gente de razón." [10] Whatever their individual feelings about the Indians, all of the missionaries were committed to instructing them in the Christian faith. At Tumacácori and elsewhere they relied on a proven daily routine. Father Reyes described it:

To excite the interest and attention of their neophytes the friars used music, processions, and feasts, bringing into play at once all the natives' senses. They were enjoined by their superiors to make a particular display of exultation at the baptism of an adult, at marriages, and at the burial of baptized infants, God's angelitos. All these occasions served as object lessons. Their superiors also affirmed the desirability of knowing the Indian language, but admitted that many of the friars did not. Instead they relied on interpreters, some of whom were sadly deficient in both languages. Reyes said that the younger Indians, and some of the older people as well, had taken to confessing in Spanish, which few of them understood. Moreover, because the concept of confession was so foreign to their own way of thinking, they often told the priest whatever they thought he wanted to hear. Or they tried to shock him: "Mujeres . . . si, Padre, tengo tres." The missionaries attempted to draw the line between what they considered wholesome Christian rejoicing and anything that suggested paganism. On some feast days, according to Reyes, "proper dances, amusements, or games are permitted. But because the missionaries try to prohibit and keep the Indians from their superstitious dances, and their scalp dances, they have had to endure bitter opposition from the authorities of those provinces who for their own entertainment and amusement want and encourage the Indians to persist in these inane ways." [11] With the troopers and settlers at Tubac to egg them on, Father Ximeno's charges doubtless exceeded at times what he judged fitting and proper. Life for the mission Indian was intended to be a continuous civilizing experience. The friars stressed externals—personal hygiene, trousers, houses with doors, civil forms of address. "In our missions," Father Cartagena wrote, "they are instructed in the respect they should show one another, removing their hat, greeting one another with the gentle words 'Hail Mary!' Those greeted respond, 'Conceived in grace!'" [12] Sixteenth-century missionaries and civil authorities had planted "civilized" Tlaxcalans as teachers and inspirations among the wild Chichimecas. As the Jesuits moved up the west coast in the following century, they had employed the same technique, settling in their missions a few families of more advanced or acculturated Indians. In Pimería Alta they used Ópatas or Yaquis, whom the Franciscans inherited. The friars, already familiar with the system from their Coahuila and Texas missions, encouraged these model families to enter into ceremonial kinship with the neophytes, serving as godparents and becoming compadres. It helped stabilize the community. In each mission there existed a standard form of local government dominated traditionally by the missionary. Through it he ordered the daily life of the community. In 1767, with the expulsion of the Jesuits, the reformers had told the Indian to govern himself. Then they brought in more missionaries. Once Gálvez returned the management of mission economics to the friars, they too began to exercise de facto the old paternalism, while at the same time pressing their case with Viceroy Bucareli for legal sanction. The annual mission "election" was never intended to be free and open. The missionary provided close supervision, seeing to it that indios ladinos, the most hispanicized of his neophytes, were chosen. At Tumacácori cooperative Indians were elected over and over. As mission justicias, they maintained order and assisted the Father in his relations with the people. In turn they learned something of how civilized men governed themselves. "The missionaries must . . . teach and make the justicias understand the obligation, love, and veneration they owe our beloved Sovereign, and that in his name they must punish the bad in moderation and serve as protectors of the good." [13] A native governor, alcalde, alguacil, and topil served in each cabecera and visita. Apparently the old mador, or herald, and the "fiscales," who assisted the missionary as catechists, were not elected but like the interpreters, sacristans, tortilla makers, cooks, house boys, foremen, vaqueros, shepherds, ox and goatherds, orchard keepers, and the like, part of the mission's specialized work force. To elevate the justicias the Father granted them certain prerogatives: in church, for example, they seated themselves on a bench while the rest of the congregation stood or sat on the floor. [14] By trial and error Father Ximeno learned to get things done around Tumacácori through Governor Miguel Antonio Becerra, Alcalde Joseph, and the others. Joseph the cook knew enough Spanish to help him with the thousand and one petty crises around the house—the disappearance of the book of sermons the Father was reading or the entire supply of lard; the chicken droppings on the Father's table; the broken decanter or dirty dishes or the plague of mice. In his dealings with his charges, Fray Bartolomé found himself relying heavily on the mission's paid interpreter, Juan Joseph Ramírez, a young español de la tierra who had grown up in the valley. A son of Juan Crisóstomo Ramírez and Bartola de la Peña, both of Tubac, Juan Joseph later married Francisca Manuela Sosa at Tumacácori and began raising a family at the mission while serving a succession of missionaries. [15] Back at the college the Father Guardian did not know where Bartolomé Ximeno was. In listing for the viceroy his friars and their duty stations, as he did annually, the Franciscan superior admitted that he had received no word about the five who left the college the previous year for the missions of Sonora: Pedro Muth, Juan Gorgoll, Bartolomé Ximeno, Matías Gallo, and Gaspar Francisco de Clemente. By November 1772 Clemente had joined Ximeno at Tumacácori. For the first time the mission had two friars, but still only one stipend. [16] The youthful Father Clemente stood more than two varas tall, probably 5'8" or 9". His face was ruddy, his hair chestnut. He came from the far north, the villa of Pancorvo whose red tile roofs huddled at the foot of a great tiered granite cliff. Through Pancorvo passed the highway from Burgos to Vitoria. In 1764 Clemente had taken that highway and the habit of a Franciscan in the order's convento in Vitoria. Five years later while a deacon at Santander on the north coast, he enlisted in the mission of 1769. [17] Of all the friars who served at Tumacácori over the years, Gaspar de Clemente, just turned twenty-seven, was the youngest. Together the two missionaries set about improving living conditions at Tumacácori. Makeshift mud and brush huts with no doors, no partitions between families, nothing but the dirt floor on which to sleep were to their way of thinking conducive only to barbarism. Some animals lived better. So they began tearing down the hovels and building proper adobe dwellings. Father Gil de Bernabé may have initiated the renewal project; Ximeno and Clemente evidently carried on. They or their successors refurbished the incommodious Tumacácori church. Around the entire complex they built a wall and hoped it would dissuade Apache marauders. At Calabazas they roofed and put into service the church and consecrated a cemetery. [18] While Ximeno and Clemente shared the burdens at Tumacácori, Father President Juan Cris&ocaute;stomo Gil fought to maintain his saintly composure. As the superior of twenty-odd missionaries in the field, the penitential Gil found it difficult to discipline others. Evidently he allowed some of the friars to take advantage of him. He was beset by unbrotherly factionalism. "It was the friars," Francisco Garcés observed several years later, "more than the Indians, who crucified and martyred him." [19] A friar's call for help could drag the Father President into profane disputes with laymen. Take the case of Fray Francisco Roche, Gil's former shipmate and neighbor. Ever since that frightful day when the Apaches sacked Soamca, Roche had lived in constant dread that the same thing would happen at Cocóspera. A near-fatal ambush heightened his fear. Now in 1772 the imperious, hot-headed Captain Joseph Antonio de Vildósola of nearby Terrenate, who had quarreled with the presidio's chaplain, was demanding that Roche take over spiritual responsibility for the entire garrison and all the settlers in the area. Moreover, some of the locals who were abusing Indians had tried to intimidate the friar. Roche complained to his Father President. Gil considered the matter so critical that he wrote directly to Viceroy Bucareli. When Captain Vildósola asked that Father Roche be assigned as chaplain, Gil refused, and, apparently reminding the officer of his own shortcomings, told him to leave the poor friar alone. That made Vildósola mad. In a most intemperate reply he all but called the Father President a liar and blackmailer. Scandalized, Gil presented the captain's letter to Governor Mateo Sastre. He wanted a formal apology. Finally, in November, 1772, Viceroy Bucareli ordered Vildósola to press the chaplain back into service and to stop bullying the missionary at Cocóspera. [20] Though he resided at Ures, Father Gil was a familiar figure on the dirt streets of San Miguel de Horcasitas, Sonora's uncourtly adobe capital. Almost everyone knew him. On his frequent visits he waged a one-man campaign against sin, and the motley mixed-blood populace flocked to the presidial chapel to hear him. He spent long afternoons hearing confessions. The sacristan recalled some years later how the Father President would sit unperturbed for hours as he and his helpers chased about the church with long poles knocking down bats, some of which fell on the friar. When he was in town Fray Juan Gil stayed at the home of don Manuel Bernardo de Monteagudo, business agent for the Franciscans. By chance one day don Manuel found in the friar's room some blood-soaked cilicios, bands of bristles or sharp netted wire worn in mortification of the flesh. "Without mortification," Gil told him, "there is no salvation." [21] As Father President, Gil had to work closely with Governor Sastre, a man of limp moral fiber. Their strained relationship became a favorite topic in the cantinas. Once when Sastre invited Gil to lodge in the governor's house, don Mateo's conduct so offended the scrupulous Franciscan that he walked out in disgust. [22] Still, Gil had to carry on negotiations with the governor. Father Garcés had requested permission through the Father President to return to the Colorado River "to see if communication can be opened between Pimería Alta and Monterey." The friars needed the support of Sastre and the Bucareli administration for the three Pápago and five Gila River missions they still hoped to found. [23] But no issue weighed heavier, or generated more controversy, than the Seri question. The big offensives of 1768 and 1769 had failed to exterminate the Seris. The war had degenerated into a harrying, search-and-destroy, guerrilla operation. In the enemy's camps it turned on hunger, smallpox, and timely offers of government rations. By the summer of 1771 a couple of hundred Seri refugees had been interned in a concentration camp at Pitic, within the bounds of modern Hermosillo. Colonel Elizondo and his veterans had already with drawn. The government had begun an irrigation project at the site. Citing the Seris' total aversion to work, their lack of respect for property, and their casual sex, as well as the government's obligation to build a church, Father Buena, Gil's predecessor, had refused to send a missionary to Pitic. Now, in the fall of 1772, as the irrigation canal neared Seri fields, the pressure was on Father President Gil. Negotiations with Governor Sastre resulted in no immediate aid, so Gil made the rounds begging. In mid-November he went to Pitic, forty miles down-river from Horcasitas. There with the governor in attendance he founded a mission, entrusting it to a thin-faced young friar named Matias Gallo. He himself had a harsher commitment. The Tiburones, a Seri subgroup who lived on and opposite jagged Tiburón Island, had asked for a missionary—in their own territory. Gil, always the penitent, always the ascetic, had promised to come. It was a risk he never should have taken. Late in November at Carrizal, an isolated and meager desert waterhole surrounded by sand, he dignified a small cluster of brush huts as Mission Dulcísimo Nombre de Jesús. He hoped to develop a salt works and fishing as mission industries, but the supplies he requested never came. He said he was content laboring alone for the Lord among the least of his creatures. All he wanted, he wrote in a letter to Governor Sastre, was to die among the Tiburones. Early in the spring of 1773 that wish and the nearly forgotten prophecy of the woman of Querétaro came together in tragedy on the barren sands of Carrizal. [24] Meanwhile, the jesuitical Antonio María de los Reyes, who had had his fill of the missionary's life, sought a higher station. No one ever accused Fray Antonio of lacking ambition. The tall, fair Franciscan had deliberately kept his name before governors, colonels, and especially José de Gálvez. In Sonora he had corresponded with the visitor general. He knew of Gálvez' plan to create a new bishopric in the northwest. When the college of Querétaro named Father Reyes its procurador, its resident agent and lobbyist at the court of México, the high-flying religious rejoiced. By the spring of 1772 he had begun the political maneuvering that would within a decade bring him a miter and staff, and cause his brothers at the college to rue the day they ever heard his name. Viceroy Bucareli was no fool. He knew that because of the great distance between Mexico City and Horcasitas "the facts regularly arrive distorted." [25] Therefore he sought the advice of persons at court who had been to the frontier. Fray Antonio de los Reyes had just returned from three years in the missions of Sonora. In April, 1772, Reyes was willing, even eager, to report to the viceroy on frontier conditions. He was no fool either. Here was his chance. "One may say without hyperbole," the friar began, "that all Sonora's terrain is one continuous mine of silver and fields of gold commonly called placers." As a promoter, Reyes ranks with New Mexico's Fray Alonso de Benavides. Having set before the viceroy the potential value of Sonora, Fray Antonio went on to describe the pitiful current state of the province. "But," he asked, "why the disparity?" God had not abandoned Sonora; nor had the Spaniard lost his courage, zeal, or spirit; rather, "by current mission and presidio policy, we have adulterated and altered completely the system of our forebears." Two great consequences had resulted. These explained the decadence of Sonora's mission frontier—the failure to stem Indian hostility and the transience of the population. Reyes, friar-turned-reformer, offered a solution, a blueprint dividing the human resources of Sonora into units in three categories: heathen missions, established Indian towns, and Spanish villas. [26] He elaborated on each, but left a number of questions unanswered. It was all too neat. How, for example, were a hundred vagabond families settled in a villa to be kept from dispersing when the next gold strike occurred over the hill? Such practical considerations never seemed to bother Reyes. With social planners like him, and like Gálvez, the plan was the important thing, not people. As procurador of the Querétaro college, Father Reyes was supposed to be working at court on the college's business, namely the withdrawal from Pimería Baja. From the beginning the friars had wanted to get rid of these establishments. Queretaran missionaries should not be relegated to administering "pueblos without heathens." Viceroy Bucareli was not so sure. He denied the college's bid to withdraw on the grounds that not enough information about the spiritual and temporal state of the Pimería Baja missions was available. [27] That gave Reyes another opening. This time in the letter transmitting his damning eighty-two-page report of July 6, 1772, Reyes the reformer called for nothing less than

Who could oppose such worthy goals? Just how he would attain them, Father Reyes did not say. Instead, by dwelling in his report on the alleged wretched state of the missions, he aimed to demonstrate at one stroke the need for change. Reyes' apparent candor pleased the viceroy. It shocked his superiors. They had their own plan. Straightaway they wrote Bucareli protesting and disavowing certain offensive passages "as foreign to our way of thinking and purpose as they are to the authority and instructions this discretory conferred upon the said Father." The irrepressible friar had clearly exceeded his authority. The superiors at Querétaro could not condone Reyes' blatant attacks on the bishops of Durango or on His Majesty's officials. It was the bishops' fault, Reyes had written, that "the churches and faithful of Sonora are in a worse state than the churches of Greece." "It would seem," he claimed elsewhere, "that the lawmakers of Sonora wanted to emulate in civil administration the confusion and disorder of the spiritual." If the viceroy would please return the report, the friars at the college would expunge the slander; if not, they asked that their protest be appended to it. Bucareli smiled. He appreciated the friars' demonstration of respect for episcopal dignity. He also appreciated Reyes' frankness. He would append the college's statement. For Fray Antonio, recalled to Querétaro, the gamble had paid off. [29] Evidently Father Reyes had access to Crown Attorney José Antonio de Areche. One week after the friar signed his report, Areche endorsed it without reservation. He recommended that Bucareli "listen with the utmost regard" to Reyes' plea. To formulate the new method he suggested that the guardian of the Querétaro college, and all other superiors with missionaries in the field, consult their most experienced men. They must consider "everything necessary for proper administration of the Indians, for instilling in them good, rational, and decent habits, a knowledge of right, humanity, society, and whatever requisite virtues should comprise or open the way to religion and enable them to confess and love God as our civilized and Catholic provinces confess and know him." On September 2, 1772, Bucareli sent Areche's statement to nine religious superiors and twenty-five governors, captains, and other officials: let there be in the missions a new method. [30] On Friday evening, March 5, 1773, Bartolomé Ximeno sat at the table in his quarters at Tumacácori writing furiously. He would tell them back at the college how it was in the missions; he would give them his comments on a new method. He was beside himself. That very morning about ten o'clock Apaches had ridden right up to the edge of the pueblo and driven off nine of the mission's eleven mares, crippling another with a lance thrust. "We were grateful they spared us our lives." Unless something were done to stop the Apaches, all the new methods in the world could not save the missions.

Tumacácori or Troy? To Father Ximeno it was as clear as that. For his superiors' benefit he reiterated how the Sobáipuris to the east in the San Pedro Valley once held back marauding Apaches, how their removal had opened the flood gates. He damned the military. "I think that on these frontiers gunpowder has lost all the power and effectiveness the Author of Nature bestowed upon it. In so many murders, robberies, and atrocities committed by Apaches since I have been at this mission, I have never heard it said that our men killed a single Apache." [31] The presidials could not even protect their own horses. At noon on October 16, 1772, Apaches had hit the Tubac herd, run off more than a hundred head, and left one soldier dead. The pursuit party caught up, but could neither take back the horses nor do the enemy appreciable harm. Several weeks later Apaches had fallen on Terrenate's caballada "under the nose" of Captain Joseph Antonio Vildósola. Killing a soldier, they got away with 257 head. The presidials who gave chase succeeded only in losing seven more horses fully saddled. [32]

No wonder the Pápagos were afraid to settle in the missions. On their own they scored an occasional impressive victory over the hated Apache enemies. The previous October a Pápago governor had presented to Captain Bernardo de Urrea of Altar "in the name of all the governors of the Pápago nation" a tally-stick on which were recorded the deaths of ten Apache men and twenty-one women. His people had captured six little girls as well. Yet they considered "the greatest triumph of their victory having killed the two parrots the Apaches had with them." [33] In the missions, said the Pápagos, the Apaches kill us. As for the state of his own mission, Ximeno told it like it was. His cabecera, Tumacácori, had twenty-three families. Even though water from the river, which they shared with the residents of Tubac, was less than abundant, at least the people of Tumacácori had their fields close at hand. At the three visitas the fields lay a league or more away and workers ran the risk of surprise attack. Eighteen families lived at Calabazas. Only nine hung on at Guevavi. The twenty-six families at Sonoita included only eleven women, so many had been killed by Apaches. The mission had hardly any livestock left: two mares of the twenty-five to thirty bands it once owned; eight horses "including lame and mistreated ones"; forty-six head of cattle of a herd that had numbered two thousand. "As for sheep and goats ... I no longer take account . . . they are at Calabazas where the miserable inhabitants who have not a bite of meat to eat are finishing them off one after the other." With the mission's population scattered as it was, not even two missionaries "though we worked indefatigably to cultivate these neophytes . . . could give them the instruction and teaching they need." When a minister sent word to one of his visitas that he would be there on a certain day, the people answered that he might as well not waste his time: they would be busy in their fields on that particular day plowing or hoeing or harvesting. They customarily moved to where their work was, "carrying their chickens and all the poor furnishings from their huts." If the friar followed he might be killed. After all, he could hardly be expected in event of Apache attack to do as his charges did—beat it into the chaparral. Ximeno suggested consolidation. The natives of distant and defenseless Guevavi and Sonoita could be brought in to form a larger pueblo at a place called Agua Fría, some six miles south of Tumacácori on the river flats. "Permanent and abundant water" made the site a natural. If the mission were reduced to only two pueblos, the people of Guevavi and Calabazas could be relocated at Agua Fría, while Sonoita's mostly male population could move to Tumacácori. Since, according to Ximeno, seventy-five percent of all those then living in the visitas were "recently converted" Pápagos—a candid statement of how far the process of replacing the dying river Pimas with Pápagos had gone by 1773—closer congregation would make it less difficult to instruct them in the faith. The question of friars managing the business end of mission administration confounded Fray Bartolomé, and he said so. Certainly temporal involvement caused "distraction and plenty of headaches." Yet what alternative was there? If the mission Indians saw that the Father had nothing to give them, they quickly lost interest. The natives themselves were incapable of taking over. "Surely in their hands nothing will bear fruit." Agents appointed from the gente de razón abused the Indians and made them work for nothing. "I simply do not have it in me to resolve the matter," admitted Ximeno. He concluded with a prayer. "May God in His infinite goodness and mercy move the hearts of those who can remedy so much adversity." [34] Later that March, Ximeno and Clemente received shocking news. Father President Juan Gil was dead. He had died violently among the Tiburones. On his last day, Saturday, March 6, Fray Juan Gil had led his neophytes away from Carrizal. The opposition, it seemed, had planted the rumor that a band of rebel Pimas was on the way to kill everyone in the mission. That night from a distance they saw Carrizal burn. Next morning Gil and his young acolyte started for the charred ruins. Four renegade Tiburón youths blocked their path. Gil yelled at his helper to run. A rock hit the friar in the chest, knocking him to his knees. The acolyte watched helplessly. The assailants kept pounding the body even after the Father was dead. When soldiers arrived they found that the people of Carrizal had buried the missionary and set up an army surplus tent over the grave. They had cut off the heads of two of the murderers and captured the alleged ringleader. They wept for the Father. Said Viceroy Bucareli in his letter of condolence to the college: Fray Juan Gil, "tenderly filled with love for his neophytes, was resolved to end his days among them. . . . Our realization of this will not lay to rest the sadness we feel as human beings at his loss, only our submission at the same time to the will of God." [35] The friars had their first Sonora martyr. Even those who had criticized him most bitterly as a superior now joined in eulogy. Fray Joseph Antonio Caxa, named to succeed Gil as Father President, designated March 8, 1774, as a day to honor the memory of his slain predecessor. Eight missionaries assembled at Ures for the solemn rite. A year later Gil's bones were exhumed and carried back to the college in a box. Fray Francisco Antonio Barbastro kept as relics the former presidente's rosary, medals, and the broken crucifix he had been wearing the day they stoned him to death. [36] His brethren gathered together his writings, removing them from the archives of the missions, the college, and elsewhere. [37] They began documenting his reputation for saintliness. The interpreter who had served him at Tumacácori confessed outright that Fray Juan Cris&ocaute;stomo was a saint. The people at Tubac reportedly wept at the mere mention of his name. Stories of an alleged miracle began to circulate. The flaccid Governor Mateo Sastre had died a few days after Gil. As he neared the end he was seized with fear for his soul. He ranted about Father Gil coming to absolve him. Deliriums, his attendants had said. Then, in the light of the friar's glorious death, they changed their minds—the martyr on his way to Heaven had indeed appeared to console his dying adversary. [38] In 1782 Father Barbastro formally opened in Sonora Gil's cause for canonization. On September 22 an announcement was read from the pulpit in Horcasitas urging those who could testify to the buen olor of Padre Gil to appear Mondays, Thursdays, or Saturdays in the morning. "Almighty God," intoned the minister,

Though witnesses did come forward, somewhere between Horcasitas and Rome the cause of Father Gil, the compassionate, self-denying Franciscan protomartyr of Sonora, was lost in the process. [40] Father Bartolomé Ximeno left Tumacácori late in the summer of 1773 after little over a year. From mid-1774 until mid-1776 he labored at the frustrating, precarious mission of Pitic where he and his compañero "found their hands tied, without authority to punish, reprimand, or even say anything to the Seris, because that was the way the government chiefs and superiors had recommended, almost commanded, they do it." [41] On a 1775 list of Querétaro friars, someone later wrote accidentado, afflicted, next to Ximeno's name. He was back at the college during the late seventies, but not listed in 1781. [42] He had served his ten years. Father Clemente stayed on at Tumacácori. By October he had a new compañero, Fray Joseph Matías Moreno, about 5' 6", pallid, pock-marked, and very eager. A year older than Clemente, Moreno was almost three years his senior as a Franciscan. He too came from the north of Spain. Born in the village of Almarza on the Río Tera, four hours' walk north of Soria, Moreno apparently considered himself a native of Logroño. His parents, Matías Moreno and María Catalina Gil, had moved to that city, where on June 21, 1761, seventeen-year-old Joseph Matías entered the Franciscan order. He excelled in his studies and could have had a university career. Instead, when the appeal from recruiter Juan Domingo Arricivita reached the convento in Burgos where he was living, "the flame leapt in Fray Joseph Matías' heart" and he joined the mission of 1769. From Madrid he wrote his devoted and pious sister exulting in his call to the college:

Moreno seemed almost obsessed with martyrdom. Eight years hence he would win his crown. The Yumas would strike off his head with an ax. The call for a new method in the missions had generated more smoke than fire. The friars in the field blamed their tribulations on the Apaches, the ineffective military, epidemics, plagues of low-life traders and vagabonds, lack of financial support, and a dozen other factors—not the old system. Some of Father Reyes' fellow missionaries accused him of arrantly deceiving the fiscal and the viceroy. It simply was not true, for example, that the Indians of Pimería Alta were still living wild and insubordinate in their native rancherías. [44] The governors and captains responded with a miscellany of diverse views. Some of them evaded the issue, making instead bland observations or suggestions, like settling the natives in formal pueblos with streets, teaching them respect for law and order, and instilling in them love of country. [45] A few, like Captain Bernardo de Urrea of Altar, had the courage to laud the friars and their method. [46] Others, taking their cue from the negative tone of the fiscal's opinion, attacked the mission system head on, but none more vehemently than Juan Bautista de Anza. [47] Anza, baptized, taught, and married by Jesuits and a lay affiliate of the Franciscans, had observed missions and missionaries all his life. He knew his subject well. But why did he damn the system with such gusto? Perhaps he had taken to heart the Enlightenment proclaimings of the reformers: perhaps he had more faith in the Indians than their missionaries did. More likely he resented the friars' hold over such a large part of the frontier labor force. Whatever his other motives, the able and ambitious career officer saw an opportunity to ingratiate himself at court. Two months earlier Fiscal Areche had whole heartedly recommended Anza's proposed overland trek to California. [48] The captain of Tubac was repaying the favor. The Indians of Pimería Alta "who used to number thousands," Anza alleged, had been reduced in the missions to a few hundred.

At the heart of the problem, as Captain Anza saw it, lay the "excessive domination and work these people are subjected to from the time they are reduced, men by their nature roving and disinclined to work they do not do of their own will." Not only did this oppressive system cause a drastic decline in native population and periodic revolts against God and king, but it scared off the heathens. Anza recalled the case of the Sobáipuris of the San Pedro Valley who had asked for missionaries in 1756.

The present system, said Anza, should be abolished. Never would the mission Indian be drawn into the mainstream of imperial life if kept in "a corner of their wretched pueblos." Furthermore these pueblos and rancherías, many pathetically small, were strewn over the countryside making proper administration and defense impossible. The king had decreed that these Indians enjoy their rightful civil liberties, and that they speak Spanish. Therefore schools must be established for the children and the adults encouraged to mingle, trade, and work with the Spaniards. "It is well known," Anza went on, "how much the contact of certain peoples with others advances them no matter how stupid they are. . . . By means of this commerce they will become Spanish-speaking and will aspire to imitate us in everything." The Indians must not be made to work long hours for the community or the traditional three days a week for the mission—a practice the captain had seen sadly abused. [50] They should instead work for themselves, experience the profit motive, and earn a stake in the community. "When they realize that they have real property, we shall be free of uprisings or fears of them." Under the new system the Indians would contribute voluntarily to the maintenance of church and priest. The friars would lay down the burden of temporal affairs. Rich missions would share with poor. Instead of a multitude of scattered villages, formal towns would rise, each with eighty to one hundred families. Fewer missionaries would be needed; and the surplus could advance into heathendom "to win countless souls for God and King." [51] Fiscal Areche was confused. There simply was no way to construct a logical program of mission reform from the farrago of conflicting reports piling up in his office. That gave the friars of the Querétaro college another chance. Fray Diego Ximénez, a twenty-year veteran of the missions distinguished by the scar of an old wound on the left side of his forehead, had replaced the scheming Reyes as procurador at court. He had successfully negotiated the transfer of the college's four Texas missions to the missionary college of Zacatecas and its two on the Río Grande in Coahuila to the Jalisco province. Now the Queretarans could devote full attention to Sonora—to getting rid of Pimería Baja, to gaining internal control of the eight missions in Pimería Alta, and to pushing on to the Río Gila and the Colorado. [52] On March 30, 1773, Ximénez presented to Viceroy Bucareli a thirteen-point plan for the missions of Sonora. Citing the decrees of previous viceroys, law codes, and the resolutions of church councils, the Franciscan sought to show how the woes of Sonora could be overcome not by innovations or reforms but by traditional methods proven in Texas. First, a guard of two or three soldiers, chosen by the missionaries but paid by the military, should be assigned to every mission. Because it took time to learn to handle Indians, these soldiers must serve on a long-term basis. They would escort the missionary on his rounds; pursue up to twenty leagues and return, but not punish, Indian runaways; oblige attendance at catechism and services; and oversee farm work, herding, and carting of building materials. Under no circumstances were the soldiers to traffic with the Indians without the expressed consent of the missionary. Father Ximénez bid next to reinstate the missionary as master of his own house. As the Indians' spiritual and temporal father the missionary must have authority to punish them. For transgressions against the church this paternal discipline should be meted out by the mission fiscales, otherwise by the pueblo's elected native officials, always under the missionary's supervision. Serious offenses should be taken before a presidial captain or the governor of the province. Speaking of captains, Ximénez added, these officials had made life miserable for the missionaries in Sonora by encouraging disrespect and insubordination among mission Indians. The Sonora missionary must have the authority, as he did in Texas and Coahuila, to supervise the work of his Indians. No one must be allowed to take Indian laborers from the missions. How, asked the friar, were churches and houses to be built and the missions maintained if the Indians were scattered over the province working for others? Work in the missions when divided among many was not oppressive, he asserted. In Texas the missionaries had also encouraged the Indians to work for themselves and to trade with Spaniards, thereby learning Spanish, respect for others, and self-reliance. All such intercourse, Ximénez was quick to add, must be overseen by the missionary: if not, the Spaniard cheated the Indian. Spaniards must not live with mission Indians. Integration before the latter were thoroughly Christianized and civilized resulted in grave consequences. Consolidation of cabeceras and visitas on the most suitable sites, with Spaniards settling the unoccupied lands—as Viceroy Bucareli had suggested—was in the opinion of Father Ximénez a worthy goal. At least then the missionary would have all his charges in view every day. Again Ximénez begged that the government provide stipends for two missionaries in every mission. He requested that captains not be permitted to influence the election of native officials. To avoid disputes over land and water he urged that each mission be granted what the law stipulated. If this were not enough, additional grants should be made, the boundaries marked, and deeds issued. Lastly, the Querétaro procurador asked that captains be forbidden to use Indian auxiliaries and scouts for extra duty as though they were unpaid soldiers or lackeys. If it pleased the viceroy to grant these requests the friars would serve God and king as both intended. [53] Fiscal Areche objected to only two of the thirteen points, the two that would cost the government money. Mission guards were unnecessary, he held, because the presidios could take care of any emergency, and two missionaries should only be provided for in missions so far apart that the missionaries could not get together with some frequency. As for the rest of what Father Ximénez wanted—sandwiched, perhaps by design, between the two costly items—Areche saw no objections. Thus Bucareli decreed on August 14, 1773. [54] The friars had won. It had taken six years but their initial burden, the instructions dictated by the Marqués de Croix in 1767, the hopeful Enlightenment reforms meant to liberate and elevate the Indian—at the same time stripping the missionary of his traditional authority—had finally been lifted by decree of Bucareli. The Queretaran friars could rule their Sonora missions in the old way, with the viceroy's sanction. The reformers be damned. Again the Jesuits would have smiled. Pleased as he must have been with his victory, Father Ximénez was of no mind to concede the guards or two missionaries permission without appeal. He asked for a copy of Areche's opinion, studied it, and on September 18 petitioned the viceroy again. The great distances between missions, which the friar gave one by one, in an enormous province harassed by Apaches certainly dictated the doubling of missionaries. To drive home the need for mission guards the friar stressed at length the ineffectiveness of the presidios, citing the reports of Reyes and that of Father Ximeno from Tumacácori. Not only would the guard serve to rally mission Indians against hostiles but also to protect the missionary from both. Soldiers at Carrizal, for example, might have prevented the murder of Father Gil. The presidial reforms set forth in the new Reglamento of 1772, Ximénez pointed out, would take years. In the meantime, if soldiers—"the missionaries' spur"—were not stationed in the missions, the Indians would "continue in the unhappy state that has prevailed till now, with the resultant miscarriage of their souls." [55] Areche would have none of it. He advised Bucareli that no simple listing of distances shed enough light on conditions in Sonora to justify the expenditure. Therefore the Querétaro college should conduct an on-site inspection, a visitation of the missions to determine 1) which ones could be consolidated or suppressed, 2) their populations and racial makeup, 3) the distances between them, and 4) whatever else seemed pertinent. With the familiar "As the fiscal says," the viceroy decreed the visita. The college had to comply. [56] The last months of 1773 Father Ximénez spent on details: a military escort for the Father Visitor and his secretary; authority for provincial officials to move a mission, found a town of gente de razón or a mission of heathens, and provide the necessary land, missionary, and soldiers. Late in November the college nominated Ximénez himself visitor and begged Bucareli to help with the expenses of the long trip. Ximénez left the capital for Querétaro. At the college he suffered severe pain, diagnosed as rheumatism, and collapsed. In his stead the friars chose a man already on the scene, the tall, slender, eagle-faced Fray Antonio Ramos, a veteran of the Texas missions who had just been named Father President of both Pimerías. [57] Hot and dusty, Father President Ramos and his escort reined up at Tumacácori early in June, 1774. For weeks they had known he was coming. In mid-April he had sent out a circular letter from Tubutama announcing the visitation. Later that month he had begun his formal inspection at Caborca, proceeding then to Ati, Tubutama, Sáric, San Ignacio, and Cocóspera, spending several days at each. At Cocóspera Fray Manuel Carrasco, secretary of the visita, must have sickened. When the visitor reached Tumacácori, he deputized Father Moreno. On the third they got down to business. The inspection began when Ramos formally ordered Father Clemente, under holy obligation, to comply with the following five demands: 1) Present a census (exhibiting the Indians so that the visitor can verify the numbers) with a breakdown of neophytes, Christians, and heathens, their tribes, marital status, and sex. 2) Give the rank or racial makeup of non-Indians. 3) State the distance to the nearest mission and presidio and to the pueblos de visita; and if the country is dangerous or not. 4) If there is any obstacle to joining the pueblos de visita to the cabecera, or the entire mission to another, as the viceroy orders for economy's sake, state it. 5) Declare whatever more may be pertinent. With Moreno as witness, Clemente bound himself to do so. [58] The 1774 Tumacácori census told a sad story—how in a year's time the mission had been forced by the Apaches to contract. Only two of the four pueblos remained. Guevavi and Sonoita lay deserted. Among the Indians at Tumacácori and Calabazas were refugees "born in pueblos that have been abandoned." Father Clemente made no distinction between Pimas and Pápagos. Ninety-eight Pimas "baptized in childhood" lived in Tumacácori (21 married couples, 5 widowers, 7 widows, 14 boys twelve and older, and 21 boys and 9 girls under twelve). On June 4 Father Ramos verified a total of one hundred thirty-eight "Pimas" at Calabazas "baptized in childhood, except for two or three" (34 married couples, 17 widowers, 4 widows, 18 boys twelve and over, 17 younger boys, 4 girls twelve and over, and 10 younger). The only non-Indians, five families (nineteen individuals) listed as "Spaniards," lived at Tumacácori, enjoyed the use of mission lands, and boasted no more assets than a single horse. [59] Still, Tumacácori's meager total of 236 Indians and 19 Spaniards made it the third most populous mission in Pimería Alta, after Caborca (535 and 33) and San Xavier del Bac (399 and 0). [60] Clemente estimated the distance to San Xavier at seventeen leagues and stressed the extreme danger of the road because of the heathen Apaches. The four leagues, more or less, south to Calabazas were no safer. A league from Tumacácori stood the presidio of Tubac, for all the good it did. As for joining Calabazas and Tumacácori, two obstacles stood in the way—the Indians' reluctance to move, and the lack at either place of sufficient irrigated land. At Tumacácori, the friar admitted, enough land could be cleared and irrigated to support the mission's entire population, were it not for "the continuous hostility of the Apache." He had nothing further to add. The Father Visitor must have noticed that most of the refugees were camped at Calabazas. They had not moved in with Calabazas families but instead maintained their old pueblo identities, the people from Guevavi in one ranchería and those of Sonoita in another, each with its own officials. Evidently they hoped to return home one day. [61] In the meantime the mission's three visitas were one, not by design but of necessity. When he had satisfied himself at Tumacácori, Father Ramos departed for San Xavier, along with Moreno and an escort. A week later they were back. The visitor had inspected the eight missions of Pimería Alta. But he could not go on. Afflicted and hardly able to ride, he called in Fray Juan Díaz, who two weeks earlier had returned to Tubac from California with Captain Anza. Then and there he named Fray Juan acting president of the missions in Pimería Baja and commissioned him to continue the visitation. In two months Díaz, having made legal copies for the college and for the archivo de las misiones, turned over the entire record to Sonora Governor Francisco Antonio Crespo at Horcasitas. The governor forwarded it to Viceroy Bucareli with comments. Crespo had little charity for the friars. Only four problem missions in Pimería Baja deserved temporary double stipends: a single síodo was enough to support missionaries in each of the rest, and actually superfluous in some. Since they had not asked him for mission guards he did not think they really needed them. On only one point did Governor Crespo concur with the missionaries—consolidation of mission pueblos, no matter how economical, was not feasible. [62] As one sympathetic friar had observed the year before:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||