Contents Foreword Preface Jesuit Foundations Gray Robes for Black 1767-68 The Archreformer Backs Down 1768-72 Tumacácori or Troy? 1772-74 The Course of Empire 1774-76 The Promise and Default of the Provincias Internas 1776-81 The Challenge of a Reforming Bishop 1781-95 A Quarrel Among Friars 1795-1808 "Corruption Has Come Among Us" 1808-20 A Trampled Guarantee 1820-28 Hanging On 1828-56 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

ON THE FEAST of Saint John the Baptist, June 24, tradition said, it would rain in Sonora. All over New Spain, rain or not, the populace celebrated with great gusto, with drinking, fireworks, and horse racing. Someone always got hurt. "Many fall from their horses, careless children are injured, and brawls and murderous deeds are always the consequence of betting." An arthritic German Jesuit, Father Joseph Och, whose worsening condition had forced him to give up his mission in Pimería Alta, would never forget the Día de San Juan of 1767, the day "our fortunes changed." Och and his brother Jesuits were enjoying a cool drink in the cloister garden of the Colegio Máximo de San Pedro y San Pablo, the order's principal house in Mexico City. About three in the afternoon a captain whom they knew strode into the garden. Grim-faced and nervous, he spoke to no one. He seemed to be looking for something. Then he left. That night, Och recalled, "all of us retired without any cares or worries, nay without even the slightest thought or suspicion of imminent misfortune." After a hectic noisy holiday, the whole city slept—except for the garrison. Silently hundreds of soldiers had taken up positions in the streets. Cavalry sat their horses in front of the viceroy's palace. Small fieldpieces aimed down the deserted streets. It rained.

A commotion in the hall outside his room awakened Father Och. It was still dark. Soldiers with fixed bayonets were everywhere. They had cut the bell ropes so that no alarm could be rung. All the Jesuits, some only half-dressed, were being herded into the chapel. At half past four, the king's minister extraordinary to New Spain, tense, square-jawed Visitor General José de Gálvez entered the chapel with the father superior. After a roll call, all present were ordered to surrender their keys. When they had done so, "a quivering and weeping secretary" read the tersely worded royal decree:

Late in July, after the summer rains had already begun in Sonora and the gnats swarmed, a detachment of soldiers from the Altar presidio rode into the mission pueblo of Guevavi, twelve hundred miles northwest of Mexico City. They had come unannounced. They demanded to see Father Custodio Ximeno. When the tall, dark-skinned young Jesuit appeared, the officer in charge thrust a vaguely worded summons at him. He told him to hand over his keys. The missionary was to speak to no one, least of all to his bewildered Pimas. While the soldiers locked the church valuables in the sacristy and arranged with the mission foreman to provide rations for the Indians, Father Custodio hastily packed a few personal belongings for a journey he must have known boded ill. Then they mounted up and led him away. [2] The sudden destruction of the Jesuits' northwest missionary empire left an immense sector of the frontier economically, socially, and defensively disoriented. As a corporation the Jesuits had dominated the agricultural production and Indian affairs of entire provinces. On the local scene they had often been the only priests and the only purveyors of health, education, and welfare. Yet some of their former neighbors were glad to be rid of the acquisitive black-robes. Others saw their banishment as a disaster. Father Custodio Ximeno's neighbor at Tubac, Captain Juan Bautista de Anza, baptized, taught, and married by Jesuits, accepted his part in the expulsion stoically. "After all, the king commands it and there may be more to it than we realize. The thoughts of men differ as much as the distance from earth to heaven." [3] Weeks before the presidials removed Ximeno from Guevavi, high-level negotiators in Mexico City had hammered out a plan for replacements. In a complex series of moves and countermoves they shifted available resources until they had filled the void, at least on paper. These reform-minded functionaries of Charles III—whose overriding concern was increasing revenue from the empire—would have preferred to secularize all the ex-Jesuit missions straightaway, to transform long-dependent mission Indians into productive, tax-paying free peasants. But few secular priests wanted, or were available, to minister to semi-heathens who could pay only in chickens and squash if at all. Although the king's social planners hoped to speed up the transition from frontier mission to parish, they did recognize in the summer of 1767 the immediate need for more missionaries.

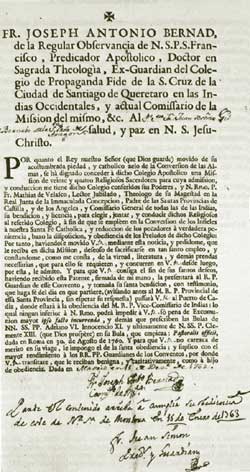

After several meetings with tough-minded Señor Gálvez and the viceroy's nephew Teodoro de Croix, Fray Manuel de Nájera, Franciscan vice commissary general for New Spain, agreed to accept the burden of the northwest missions. Viceroy the Marqués de Croix professed to favor the Franciscan missionary colleges whose friars were already at work on the frontier east of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Nájera checked the rosters. The colleges could supply fifty-one men. The rest of the replacements would have to come from the Franciscan provinces. In mid-July couriers rode northwest out of the capital with letters from the viceroy and from Nájera for the Father Guardian of the Colegio de la Santa Cruz de Querétaro. [4] The college, a sprawling gray-stone complex on a hill not far from Querétaro's famed aqueduct, had maintained its reputation for discipline and zeal even at a time when laxity among mendicant friars was the object of vulgar satire. During the previous century there had been a critical shortage of missionaries for work on New Spain's heathen frontiers. The Jesuits had responded by importing Germans, Italians, and Flemings. The Franciscans in 1683 had founded the college of Querétaro, the first New World training school to supply missionaries to faithful and heathen alike. From the beginning small bands of Queretaran friars, whose gray habits of undyed wool were intended to remind them of the poverty, self-denial, and discipline of Saint Francis, had traveled the length and breadth of New Spain preaching soul-stirring home mission to sinning Christians. In the wake of the LaSalle scare, they had reached out to the non-Christian Indians of east Texas. They had joined the bold and strutting Diego de Vargas in his reconquest of New Mexico where one of them died a martyr in the Pueblo revolt of 1696. They had taken cuttings from the stock of the original vine and had planted new colleges in Guatemala, Zacatecas, and Mexico City. In the summer of 1767 the mother college administered heathen missions in northern Coahuila and in Texas around San Antonio. The superiors had just pulled back their apostolic workers from a barren field. Not even Saint Paul could convert the Lipan Apaches. Within the administrative framework of the Order of Friars Minor, the New World missionary colleges enjoyed a privileged if ill-defined autonomy in relation to the broad units known as provinces, some of which maintained missions of their own. The colleges were governed internally by a Father Guardian and his advisory council, or discretory, elected for three-year terms by the community in chapter. They answered directly to the Franciscan commissary general of the Indies at Madrid through his vice commissary for New Spain. At times rivalry between the grayrobes of the colleges and the bluerobes of the provinces resulted in wholesome competition, at times in unbrotherly dissension. The Querétaro college did not offer formal graduate courses in missionary technique, arts, or crafts, but rather a severe, self-denying existence designed to build apostles. It provided a disciplined atmosphere for prayer and recollection, an emphasis on moral theology and preaching, and the opportunity to practice by giving home missions. It served as a base of operations for missionaries, from which they went forth full of zeal and to which they retired for rest and recuperation. Only a few criollos, Spaniards born in America, gained entrance to the college. Most of the friars came directly from Spain at royal expense in groups called "missions" which were recruited periodically to maintain a set quota of active members. Ten years' service in the missions was required before a Spaniard could petition to return home. Most spent the rest of their lives in Spanish America, either staying on as members of the college or joining one of the Mexican provinces. [5] Late in 1763 twenty-three Spanish recruits had arrived at the college. After four years of home missions some fairly begged to try their hand entre infieles. The viceroy wanted at least twelve, preferably fourteen, replacements from the college of Querétaro for the vacant missions of Sonora. They must leave as soon as possible, travel to the Pacific coast, and there board the ships that carried south the expelled Jesuits. Once they reached the missions they were to be paid, at least for the time being, an annual 360-peso sínodo, or royal allowance. The viceroy's instructions to the Queretaran friars left no doubt that the government meant to depart drastically from traditional missionary policy. The viceroy made it clear that theirs was to be a spiritual ministry only: government agents would manage the temporal business of the missions, and hopefully show a profit. At the same time the reformers would instantly raise the status of the downtrodden mission Indian. "Under no circumstances," the viceroy ordered, "are Indians to be deprived of civil intercourse, communication, commerce, or residence with Spaniards, no less the possession in individual and private domain of their property, goods, and the fruits of their labor." [6] The friars were stunned. The reformers were asking them to take over the vacant missions of Sonora and at the same time denying them the authority to administer them. Stewardship of mission produce and paternal discipline of mission Indians lay at the heart of the system. If he did not give them their daily bread and a set of rules to regulate their relations with non-Indians and to protect them from the advances of greedy Spaniards and half-breeds, how could a missionary hope to guide his neophytes toward spiritual and civil betterment? He simply could not, said the veterans. Commissary General Nájera stressed the urgency of the replacement operation. There was no time for debate. Fourteen friars must be named and outfitted without delay. Fifteen volunteered. That left the college so understaffed that it had to refuse requests for home missions. When the local treasury official told the superiors that he had no orders from Gálvez or the viceroy to provision the replacements or to pay their travel expenses as far as Guadalajara, the college had to dip into its monies from Masses and donations. [7] At the hour of prime, about five thirty in the morning, on August 5, 1767, the entire household of the college assembled in the church for a moving farewell service. Just before their departure the fifteen gathered in the refectory to hear over their breakfast chocolate the viceroy's letter and an eight-point set of instructions from their superiors. In Sonora the substitute missionaries would (1) treat their charges with paternal love; (2) report accurately on their new physical and human surroundings and suggest means of expanding the missions and incorporating heathens; (3) submit these reports through the Father President, their superior in the field, and write nothing secret or damning about anything or anyone, unless absolutely unavoidable, and only then with the utmost discretion; (4) under no circumstances prevent civil intercourse between their Indians and Spaniards; (5) confine themselves to spiritual administration only, encouraging the Indians to become self-sufficient in temporal matters; (6) see that the Indians learned and spoke only Spanish and, ideally, sponsor a school in each mission; (7) receive by formal inventory the furnishings of church and Padre's quarters noting in particular that baptismal, marriage, and burial books were in order, and compile a detailed census of mission residents; and (8) exercise the ecclesiastical faculties granted them directly by their prefect apostolic on authority from Rome, and in the event of opposition from a representative of the bishop avoid a showdown and report to the Father President. The friars had complied, but to them these instructions were clearly provisional, to serve only until on-site experience dictated a wiser, more realistic course. Tough old Fray Mariano Antonio Buena y Alcalde, veteran of the Texas missions, led the Queretaran replacements as Father President. He was also prefect apostolic for all the Franciscan colleges in America, a position which invested him with broad ecclesiastical authority from the Sacred Congregation of the Propagation of the Faith in Rome, authority usually reserved to bishops. [8] Taking the highway west out of Querétaro the fifteen grayrobes made for Guadalajara, a pleasant journey of two hundred miles. After a short layover they hired a guide and animals and pushed on. At Magdalena one of them fell ill and had to be treated. On through towering green mountains they rode, finally dropping down August 26 into the bustling, rowdy town of Tepic, still high enough above the steaming tropical coast to be comfortable. The streets and cantinas were jammed. Everywhere they looked were soldiers, hundreds of them, units of Colonel Domingo Elizondo's touted expeditionary force bound for Sonora to humble once and for all the wild Seri Indians and their rebel Pima allies. [9] The friars sought out the Franciscan hospice of Santa Cruz de Zacate where they would stay until told to go down to the sea. It was packed, too. Father Junípero Serra and a dozen others from the college of San Fernando in Mexico City waited for orders and ships to sail for Baja California. Blue-robes from the Jalisco province of Santiago, to which the hospice belonged, also checked in. They too would take over some of the ex-Jesuit missions of Sonora and those of Nayarit. By the middle of September forty-seven friars destined for the missions had crowded into the hospice. [10] Through no fault of their own, the replacements would be delayed in Tepic for months, hearing confessions, doing their spiritual exercises, preaching, and counting the days. Meanwhile, seven hundred miles to the north, soldiers stood guard outside the squat, century-old church at Matape. Inside, some fifty Jesuits, the ex-missionaries of Sonora, heard the decree of expulsion read formally. Behind them in the missions, hungry neighbors, Spaniards and mixed bloods, convinced that a Jesuit monopoly of land and labor had kept them poor for generations, set about looting what they could get away with. Mission Indians joined in. The Indians were confused. For as long as they could remember black-robed Jesuits had represented authority; neither soldier nor settler had got the better of them. Now in village plazas all over the province Indians were congregated and told to forget the Jesuits, the king would protect them. That they had heard before. But now he was promising them a new deal—freedom, civil rights, and education—the Enlightenment by decree on the Sonora frontier. [11] Henceforth no Indian had to work for a missionary or anyone else without a fair day's pay. That they could understand: they did not have to work. Henceforth they were desegregated. Indians might come and go as they chose, treat, do business, or even live with non-Indians, as if all were brothers. There seemed to be no end to the promises—private property, village schools, parish priests. The vision of these former wards of the Jesuits, newly independent, working their own milpas, speaking Spanish, and enjoying the right—and paying the taxes—of full citizens was a satisfying and progressive one. But it was only a vision. The reformers, betraying from the start a notable lack of faith in the Indians they sought to elevate, now designated temporary royal managers to look after the temporalities, that is, the common fields, herds, and other assets of the missions; to collect accounts receivable and pay debts; and to hold in trust what really belonged to the natives. Recruited from the ruling but often destitute citizen-soldier stratum of frontier society, most of these lay comisarios acted predictably. They cheated the Indians, whom they looked upon as fit only to serve. They sold off, appropriated, or let deteriorate the property of the missions, which they considered ill-gotten in the first place. And the most boorish of them toasted their health with sacramental wine. [12] Captain Bernardo de Urrea of Altar, reluctant overseer of the Jesuit expulsion in Pimería Alta, named don Andrés Grijalva comisario for the three vacant missions of Soamca, Guevavi, and San Xavier del Bac. A civilian resident at the presidio of Terrenate, Grijalva had worked for Urrea on the captain's estancia northwest of Tubac at least as early as the 1740s. His brother Juan had run stock in the San Luis Valley south of Guevavi until chased out by Apaches in 1764. [13] Don Andrés knew well the missions and Indians whose temporal master he became in the summer of 1767. Perhaps genuinely imbued with the spirit of the Enlightenment, or perhaps just to see what would happen, Comisario Grijalva rode to Guevavi and proclaimed to the natives that they were now absolute owners of the mission's property. It was theirs to dispose of however they wished. He handed them the keys to the granaries. What resulted at Tumacácori, Guevavi's northernmost visita, did not amuse Captain Juan Bautista de Anza. "In but a few days," Anza reported to the governor of Sonora early in September,

Captain Anza had reason to be annoyed. With the whole province girding for war against the Seris and rebel Pimas to the south, he simply could not sit back and let Tumacácori's gluttonous Indians eat up all available provisions. Thanks to his quick action, Anza assured the governor, he could still meet his quota of pinole, meat, and up to a hundred native auxiliaries from Soamca, Guevavi, and San Xavier. [14] During their interlude without a missionary, the people of Guevavi and its three visitas cannot have noticed much improvement in their lot. They still had to work, for a comisario instead of a Padre. Somehow they never saw that fair day's pay. The new deal, they were told, required sacrifice. They could do their part by producing a surplus of food. Meanwhile their smiling new brothers traded them tawdry merchandise for staples. As a result some went hungry. Some abandoned their families and wandered from pueblo to pueblo, abusing their new liberty and committing depredations of their own. Private property meant nothing: they no longer had the keys. Their spiritual life, such as it was, degenerated. Only occasionally did anyone preach to them. For all Pimería Alta, fifty thousand square miles, there were only a couple of circuit-riding parish priests, young Miguel El&ieacute;as González and veteran Joseph Nicolás de Mesa, sometime curate at the presidio of Altar a hundred miles southwest, "a zealous minister, a good moralist, with no other fault than fondness for gambling." [15] As if the abuse of their neighbors and the hunger in the pit of their stomachs were not enough, the mission Indians lived in mounting anticipation of Apache attack. When Captain Anza arrived at Guevavi to harangue and sign up warriors for the southern campaign, the rest knew what could happen. They knew as well as Anza did that the Apaches would wait till most of the forces of Sonora were committed to the Seri offensive, then strike. A captive who had escaped from the hostiles warned Anza that it looked bad for the coming winter. Because they expected handouts, a condition of peace treaties proposed by the Spaniards, the Apaches had planted nothing. Thus when rumors of Spanish treachery wrecked the chance for peace, the ill-provisioned Indians were more determined than ever to take what they could by force. "Never," Anza admitted to the governor, "have the missions been worse cared for than they are now." [16] Early that winter they struck. A screaming Apache war party rode down on the horse herd belonging to the presidio of Terrenate, killing one soldier and taking captive a soldier and a settler. Like the frontier cavalry, the attackers wore protective leather coats and wielded lances. Pursued by troops, the Apaches slew the two captives and wheeled around to fight. The presidials lost heart and withdrew. Swinging to the northwest the hostiles made for Guevavi, where on November 2, All Souls' Day, the already alerted mission Indians fortified themselves in the convento. The Apaches rode off, this time without causing damage or loss of life. [17] Far to the south in Tepic the Queretarans still waited. So did the soldiers. Because José de Gálvez had resolved that Elizondo's entire expeditionary force, including the missionary replacements, should move north by sea rather than land, everyone waited on ships. At the overcrowded hospice of Santa Cruz de Zacate a crisis developed. The viceroy had juggled missionary assignments. Bluerobes from the Jalisco province were to proceed to Baja California instead of Sonora, ostensibly because they and the grayrobes of the Querétaro college could not get along together. Father President Buena, offended by the allegation that his men had quarreled with the Jaliscans, took testimony to the contrary. Father Serra's band made it known that if denied California they would rather return to their college. The change, it appeared, was political. For an explanation Serra sent two friars inland to confer with the powerful Gálvez. Meanwhile the Jaliscans sailed. In mid-November, thanks to Gálvez, they were called back and the original assignments restored. [18] Finally, after months of frustration, the Queretarans received orders to sail. On January 17, 1768, thirteen of them left the hospice in Tepic and journeyed the forty miles down to the port of San Blas, part of the way through towering jungle forest. One stayed behind to serve as chaplain on a ship sailing later. Another would travel overland with Colonel Elizondo and his dragoons. The rest of the friars and most of the troops crowded aboard two coastal packet-boats, the newly built San Carlos and the puny Lauretana, for a nightmarish voyage none would ever forget. [19] Beating up the treacherous Gulf of California, alternately becalmed and caught in sudden furious chubascos, taxed crews and ships alike. It often meant several false starts. Colonel Elizondo had only decided to ride north on terra firma after enduring a miserable voyage and a shattered mainmast aboard the San Carlos, only to find himself back at San Blas. [20] Again on January 20 the refitted San Carlos weighed anchor for the port of Guaymas with its cargo of friars and soldiers, and again, after forty days of "frightful experiences, fears, and hardships" at sea, she limped back to San Bias. As Father Serra and his contingent prepared to embark for Baja California in March they consoled a dejected but still determined Father Buena and five other Queretarans. The Lauretana meanwhile lay in the harbor at Mazatlan with one friar standing by. The remaining six, terribly sick and exhausted, preferred to walk the last five hundred miles. [21] First to reach Sonora was Colonel Elizondo's chaplain, tall, blond and balding, long-faced Fray Antonio María de los Reyes. Urbane and ambitious, Fray Antonio got on well with people of high station, so well in fact that fifteen years hence he would be consecrated Sonora's first bishop. He had ingratiated himself with the colonel, who later wrote the governor requesting that Reyes be assigned to the mission nearest the expedition's theater of operations. [22]

At Guaymas when Reyes met Governor Juan Claudio de Pineda, the fat catalán who had managed the Jesuit expulsion so efficiently, he urged that the Queretarans be given the missions most recently established, those adjacent to heathen peoples. They had come, said the friar, to propagate the faith among heathens, not to fill in as "forced vicars of the secular clergy." [23] In the matter of who should get which missions Governor Pineda had already heard from the famed bishop of Durango, Dr. Pedro Tamarón y Romeral. The bishop, whose immense diocese sprawled north a thousand miles to take in New Mexico and Sonora, volunteered to fill all the vacant missions of Sonora with parish priests, though he never made clear just where he would get so many. Even after the viceroy notified him that dozens of friars were on their way, Tamarón insisted that he could recruit thirty or forty seculars and install them himself. "I do not know how my letters have been interpreted at the viceregal court," he complained to Pineda. [24] As a courtesy, Father President Buena had formally requested the general faculties for him and his fourteen friars to function as priests in the diocese. Bishop Tamarón granted them promptly. But friars or no friars, the bishop still wanted Governor Pineda to save at least some of the most productive and desirable missions for his clergy. The governor agreed. By the time the Franciscans began arriving, Pineda had decided where to place them. To avoid disputes he would separate the grayrobes of the Querétaro college from the bluerobes of the Jalisco province and both from the secular clergy. Each group would work in a defined geographical and cultural region. He could negotiate the specifics with Bishop Tamarón later. [25] The six put ashore at Mazatlan made it to Sonora early in the spring of 1768. Because their coming coincided with a raging epidemic, they traveled from pueblo to pueblo offering what consolation they could. [26] Governor Pineda, on his way north from Guaymas in late March, ran into three of the grayrobes at Buenavista on the Río Yaqui. Not waiting for Father President Buena, he tentatively assigned the early arrivals to missions. "I provided them with the necessary horses and mules so that they could get themselves to the places I designated, those where missionaries are most needed." [27] Seven weeks later, in May, Father Buena and the others stumbled onto the beach at Guaymas. Though the Father President suffered from painful hemorrhoids and a urinary disorder picked up during the voyage he insisted after only four days' rest that they push on to the presidial town of San Miguel de Horcasitas, residence of Governor Pineda. Because the Seri stronghold lay due north of Guaymas, the friars detoured southeast, then followed the Río Yaqui north. Passing through the populous Yaqui missions Father President Buena happily assumed that their own mission assignments would be similar. Yet as they proceeded upriver the scene changed. The missions looked desolate. "I began to be disenchanted," wrote Buena. "The ones that have been given to us are the least populous, the poorest and most painful, located in the only unhealthful climate in all these vast provinces." While six of his band provisioned themselves at the sprawling, dilapidated mission of Ures, long a travelers' haven at one of Sonora's major crossroads, the Father President presented his credentials to the governor at Horcasitas. The ailing Franciscan pleaded that all of the Queretarans be assigned to missions farther on, nearer heathens. But the obese governor had made up his mind. He had already dispatched some of the friars himself. Buena could see that it was no use. Besides, the Father President did not want it said "that our College was seeking after plenty and ease by refusing to shoulder a heavier cross." [28] The grayrobes from Querétaro had drawn all eight missions of Pimería Alta, the most northerly and heathen of all, which suited them. The other six, some of which they had already seen, strung out for two hundred miles along a north-south axis through the heart of Sonora in what was loosely termed Pimería Baja. Longer established, hopelessly mixed racially, and run-down, these they would willingly have given to Bishop Tamarón. Pairing men with missions the Father President and the governor came up with the following complete roster:

After only four days at San Ignacio, southernmost of the Pimería Alta missions, Father President Buena decided to move his headquarters closer to the heathen nations. He rode northwest to Tubutama on the Río Altar where the last Jesuit superior had lived. From Tubutama the President wrote to Fray Juan Crisóstomo Gil de Bernabé confirming his ministry at Guevavi, its three visitas—Sonoita, Calabazas, and Tumacácori—and the presidio of Tubac. By late June, 1768, when Fray Francisco Garcés reached San Xavier del Bac near Tucson, all the Queretaran replacements had taken up their respective crosses. Governor Pineda sent word to Andrés Grijalva and the other comisarios to surrender to the Franciscans by formal inventory the churches, sacristies, and Padres' quarters, along with what furnishings they contained, but no more. [29] Certainly there was no love lost between Jesuits and Franciscans. Some elitist Jesuits looked only with disdain on members of the mendicant orders. One Spanish Jesuit, a decade before the expulsion, had written a novel satirizing the preaching of ignorant friars. Yet the plight of the Jesuit expulsos of Sonora moved the Franciscans to pity. Not until mid-May 1768, after more than nine months of mean confinement, were the fifty haggard blackrobes embarked at Guaymas on their via dolorosa south. Twenty-four days later their ship, badly battered by consistently adverse winds, put in to the port of Loreto in Baja California for repairs, food, and water. When Fray Junípero Serra heard the news, he hastened down to the beach. There in the searing sun he tried to console the wretched, half-crazed sons of Saint Ignatius. [30] In Pimería Alta, northernmost extension of the Jesuits' fallen missionary empire, the replacement operation was complete. The reformers had traded black robes for gray. In the process they had thrown the mission frontier into disorder. Almost to a man the Franciscans were appalled at what they found. Fray Juan Crisóstomo Gil de Bernabé at Guevavi suffered as the rest. He bore an additional burden—the prophecy that he would die in Sonora. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||