Contents Foreword Preface Jesuit Foundations Gray Robes for Black 1767-68 The Archreformer Backs Down 1768-72 Tumacácori or Troy? 1772-74 The Course of Empire 1774-76 The Promise and Default of the Provincias Internas 1776-81 The Challenge of a Reforming Bishop 1781-95 A Quarrel Among Friars 1795-1808 "Corruption Has Come Among Us" 1808-20 A Trampled Guarantee 1820-28 Hanging On 1828-56 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

FOR SEVERAL WEEKS after the others had departed, the lonely twenty-seven-year-old Fray José María Pérez Llera stayed at Ures feeling sorry for himself.

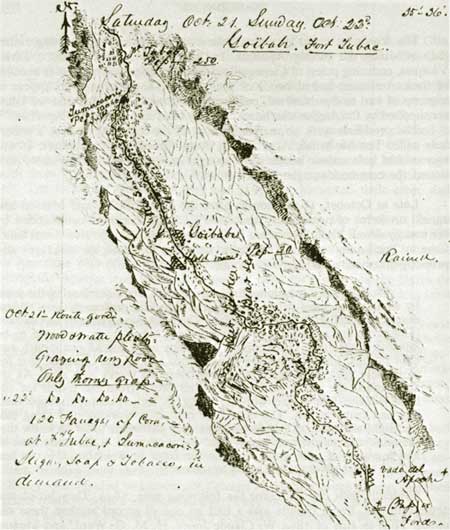

By mid-July, the worst time of year to travel because of the summer rains, he had got hold of himself. To fulfill his superior's parting commission Father Pérez Llera intended to visit the missions and get back to Ures as quickly as he could. At San Ignacio a revelation struck him, changing his fear to confidence. "God Our Lord would not forsake me so long as I dedicated myself to the good of these poor souls." In a few days Fray Rafael Díaz joined him, having secured a permit to remain in Mexico. Now there were two of them. From the perspective of San Ignacio the missions and settlements of Pimería Alta divided naturally into two sectors: those to the west and those to the north. Pérez Llera took San Ignacio and the west—Tubutama, Oquitoa, and Caborca, with all their visitas. Sáric, abandoned in 1827 because of the Apaches, he left off the list. Díaz took the north—Cocóspera, Tumacácori, and his old mission of San Xavier del Bac, plus the presidios of Santa Cruz, Tubac, and Tucson. Never again would the missions be fully manned. The day of the resident missionary-protector had passed. Yet inertia, the disarray of their opponents, and the presence of the last few grayrobes kept the missions alive, if barely, long beyond their time. [1] Father Díaz was none too certain about his new status as a naturalized Mexican, even though he had resided in the country for at least a decade. Born October 24, 1794, in the wine-making center of Jerez de la Frontera just north of Cádiz, he may have emigrated to New Spain with his family during the prolonged French troubles. He had entered the order in the province of Michoacán two days before his twenty-fourth birthday. In 1820 he transferred to the college of Querétaro and four years later found himself assigned to its farthest mission, San Xavier del Bac. From 1824 until the expulsion in 1828 Rafael Díaz had done double duty as missionary at Bac and as interim chaplain of the Tucson garrison. Now late in the summer of 1828 he decided for his own good to return to Tucson until the frenzied prejudice against Spaniards subsided. "As a result," reflected Pérez Llera, "I was again alone, with almost all the pueblos." [2] The circling vultures moved in to pick the missions' bones almost immediately, to hear Father Pérez Llera tell it. Reports of graft and mismanagement, by or in spite of the hastily chosen mission overseers, piled up on the governor's desk. As a result Vice Governor José María Almada charged the repentant alcalde of Altar, Santiago Redondo, and one don Fernando Grande to visit the missions and report fully on the state of their economic affairs. Debtors and creditors were clamoring. The vice governor ordered don Manuel Escalante y Arvizu, jefe político of the department of Arizpe, to confiscate the more than three thousand pesos "collected by don Ignacio Elías and other individuals by order of the expelled Spanish religious." Fray Rafael Díaz tried to compile a list of persons who owed debts to the missions. Don Leonardo Escalante of Bacoachi claimed that Tumacácori owed him three hundred head of cattle. Fray Ramón Liberós had given a colt to the commandant at Tucson, presumably Pedro Villaescusa: it and fourteen purchased she-asses had been reclaimed. The officer demanded justice. [3] To straighten out accounts, take inventory, and assess the mission's future, don Fernando Grande came to Tumacácori late in the summer of 1828. Ramón Pamplona, despite "his lack of instruction in accounts and the management of these affairs," had done a creditable job. He had paid off some of the 1,115 pesos in debts resulting from church construction. The various creditors who had received payment, including the Ortiz brothers Tomás and Ignacio, owners of the Arivaca and La Canoa grants, were obliged to submit an accounting to the state government: any payment not approved they had to return. At the time of his rude separation from Tumacácori, Father Liberós had given gifts—technically not his to give—to some of the Indians who had served him well: a mare, a horse, a cow, or clothing. The total value, Fernando Grande estimated, cannot have exceeded a hundred or a hundred and fifty pesos. To avoid stirring up resentment among the recipients, Grande decided to write off these gifts. Besides, "being Indians and poor" all had eaten, sold, or traded the animals for things they needed more. The mission's assets from supply contracts made by Father Liberós with the presidios of Tubac, Tucson, and Santa Cruz amounted to 1,516 pesos, plus an additional three hundred pesos' worth of wheat for Tubac. At this time a fanega of wheat and a cow on the range were on a parity, each worth three pesos. Two of Tumacácori's four wheat fields were leased to don Ignacio Ortiz at the rate of one fourth the yield. Like everything else, this was now subject to government approval. In his report Grande praised the way the Indian Ramón Pamplona had administered Tumacácori. But, according to Grande, Pamplona refused to remain in office "even though I tried hard to persuade him . . . offering to assign him a salary." Don Tomás Ortiz stepped forward. He would oversee mission temporalities for forty pesos per month, the equivalent of a hundred and sixty cattle a year. In the presence of Grande and the alcalde of Tubac, Ortiz signed the inventories making himself accountable. His business concluded, Fernando Grande rode south to Cocóspera where he deposed Nicolás Martínez, the Indian left in charge there by Father Francisco Solano García. It was no secret that Grande wanted to be general administrator of mission temporalities for all Pimería Alta. After he had inspected Tumacácori, Cocóspera, and San Ignacio, he made three observations to the government: (1) The missions must be preserved as economic entities in order to civilize and educate the Indians to the new order. (2) If the missions, which the Indians understand to be theirs, are suppressed, these long-loyal peoples, full of resentment, will rock the frontier with violent upheavals. (3) The state will benefit to the greatest degree by establishing a general mission administration, imposing annually a sum to be paid into the treasury, and permitting the missions to supply presidios and settlers as in the past. He did not mean to laud the ex-missionaries' economic regime—they had their own propagandists—only to stress the reality of the situation. [4] Father Pérez Llera resented it when General Administrator Grande moved in with him at San Ignacio. The friar soon found himself reduced to a single room in the convento and driven half crazy by the children's ruckus. He was dependent on the administrator for meat, flour, and practically every thing else, though he did manage to win control of the missions' kitchen gardens. It galled him that Grande was drawing a one-hundred-peso-a-month salary plus expenses, and that the administrator's chosen subordinates enjoyed proportionate salaries. The disgruntled Franciscan put up with the arrangement for several months, "until I saw that everything was being exhausted at a rapid rate and that the Indians would be more responsive to us if we were in charge of everything and could protect them from the injustices being done them by the settlers." He petitioned the government to turn the temporalities back over to him, Díaz, and the other friars they hoped would soon join them. [5] At Tumacácori something went wrong. Jefe Político Manuel Escalante y Arvizu admonished don Tomás Ortiz to share with him whatever bright ideas he had regarding the mission. He also told the Tumacácori administrator to remedy certain inequities immediately. For whatever reason, Ortiz was replaced in 1829 by a Grande appointee, Buenaventura López. During November and December that year the volatile Escalante y Arvizu visited the missions for himself. He was shocked. He listened to the Indians complaints and saw their deplorable condition. Under the friars the Indians had at least benefited from the sweat of their brows: they had been fed, clothed, and housed. Now they benefited not at all. As a result, noted the jefe, they were leaving the missions and wandering about, trading oppression for the freedom of vagabonds. Escalante y Arvizu supported Father Pérez Llera one hundred percent. There were now four missionaries in the Pimería: Pérez Llera, named Father President by the college, at San Ignacio; Rafael Díaz residing currently at Cocóspera and ministering to Tumacácori, San Xavier, and the presidios of Santa Cruz, Tubac, and Tucson; Juan Maldonado who had returned to Pimería Alta after an absence and was serving Oquitoa and Tubutama; and Faustino González, "a very ill Spaniard," at Caborca. "American-born religious," Escalante y Arvizu asserted, "are no less capable than Spaniards: the latter, with hand out and with less interest in our happiness, had in their charge the management of the economic affairs of these missions; why should not the former?" If not returned to the friars immediately, everything the missions owned would end up in the hands of others. The Apaches would finish off the livestock. And likely the Pimas would rebel. [6] A creature of the oppressive Gaxiola-Paredes administration, Fernando Grande fell shortly after it did. The proposal of Father Pérez Llera and Jefe Político Escalante y Arvizu found favor with the new government, and on January 22, 1830, the mission properties reverted to the friars' care. That spring Grande and Pérez Llera made the rounds together effecting the transfer of what was left at each mission. On May 4 the Mexican Father President signed a receipt for Tumacácori 'with its books and accounts." Grande's appointee Buenaventura López had been sharing local administration with Ramón Pamplona. Tumacácori, at latitude 31°47' and longitude 33°42' west of the meridian of Washington (not far off the actual lat. 31°34' and long. 111°3' west of Greenwich), wrote Grande in his final report, "has some Indian families, though their number is not great, and some settlers supported by the temporalities as day-laborers because of the shortage of hands." [7] The temporalities Pérez Llera signed for at Tumacácori in 1830 reflected a drastic decline in what Liberós had left two years before. Whether greedy settlers or Apaches were more to blame was difficult to assess. Many of the mission's estimated four hundred remaining cattle ran wild because the people of Calabazas who herded them had been chased from their homes by Apaches. The mission still claimed some eight hundred head of sheep. The few horses had all gone wild. Much of the wheat-growing land was unplanted because of the Apache peril and a lack of demand. The church the friar described as "good, new, and well enough supplied," and the convento "likewise." [8] During the nine months Fernando Grande functioned as general administrator, the insecure Franciscans did not dare indict him for the rape of the missions. Besides, no one had enough to pay them back anyway. But once Grande had departed, Pérez Llera unburdened himself to the governor.

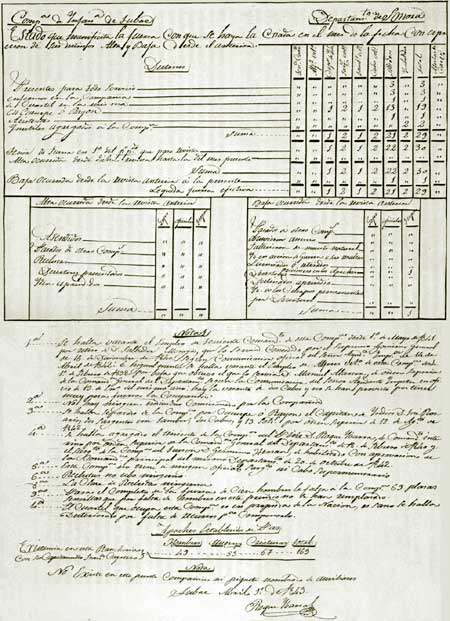

In his reminiscences the friar told what had happened at San Ignacio. When Grande arrived there had been six hundred pesos in cash, plus crops and livestock. When Grande left "I received not a half-real of it, but instead debts and eleven cattle that were so old and skinny no one wanted them. And because there had been takers not even the wooden chairs in the quarters had escaped." The moral wreckage, according to the Father President, was even worse than the physical. Mission Indians had been abused and corrupted. They had got used to license and vice. Some had run away, back to their heathen relations. Venal officials encouraged the dissipation. Such, wrote Pérez Llera, "is the sickness of our Babylon." He begged for the governor's support. [10] Evidently Grande did have something to hide. When don Leonardo Escalante, provisional governor of separated Sonora, reported in August, 1831, to the minister of justice and ecclesiastical affairs in Mexico City, he explained that the documents setting forth the state of the missions during their civil administration had been carried off to Durango. His appeals had brought not even a reply. The governor admitted a staggering debt owed to the missions by individuals, presidios, and the government. He was confident that they would not lose any more under the direction of Father President Pérez Llera, "whose honesty and integrity are well known to the entire state," except to the barbarous Apaches. He closed with an appeal for priests and a prophecy of hope.

The Father President himself would not have gone so far. But he did share some of Governor Escalante's hope for better times. He had ridden to Pitic, since 1828 called Hermosillo. In audiences with the governor and with members of the state legislature his suggestions for reform of the missions had been well received. At his urging they had passed a law setting the clock back in the missions to before the expulsion of 1828. Henceforth the Indians of the missions were subject to their missionaries, just as before. Henceforth heathens were forbidden to wander around corrupting and being corrupted in the established settlements. But it would take more than a law. [12] The prospects for Sonora did seem brighter in 1831. The federal congress had approved the division of the Estado de Occidente into the two separate states of Sinaloa and Sonora. With that disruptive issue resolved and a constitution of their own, the leaders of Sonora could presumably get on with developing the potential of their state. On May 1, 1832, don Manuel Escalante y Arvizu, ex-jefe político of Arizpe, took office as the first constitutionally elected governor and proceeded to the feat of serving a full four-year term. Arizpe, because of foreboding pressure brought to bear by the military under Comandante Simón Elías González, won the honor as state capital. But not all was well. Open fights between political factions, barrack revolts in support of the latest national uprising of Santa Anna, appeals to the Indian tribes by all sides, a fresh outbreak among the Yaquis, and the resultant lawlessness, confusion, and poverty made the statement of ex-governor Leonardo Escalante a travesty. Even without hostile Apaches there would have been little hope of a renaissance in Pimería Alta. With the Apaches, there was none. Even though the energetic, thrill-seeking Governor Escalante y Arvizu, who spent much of his term dashing from one crisis to the next, campaigned against them as far as the Río Gila and the Sierra de Mogollón, the Apaches continued to come and go almost at will. The tide of their depredations was again in full flow: it would not turn for a generation, until well after the abandonment of Tumacácori by the last Indians. [13] Even as Father Ramón Liberós had made his final hurried arrangements at Tumacácori in mid-April, 1828, an Apache war party attacked and massacred seven settlers at the placers just to the west "in the sierrita" between the rancho of Arivaca and the presidio of Tubac. [14] No one was safe on the roads or in the fields without an armed escort. They learned to live with the peril. In December, 1829, Buenaventura López had told Fernando Grande what it was like at Tumacácori. Early the morning of the seventh an Indian reported that he had noticed a commotion and heard yelling as he passed the place called Agua Fría, six miles south of Tumacácori. Near there the mission's horses had been grazing. All who could assembled and went to investigate. Soldiers, settlers, and Apaches mansos from Tubac followed. The horses were gone and no one could find vaquero Leonardo Ochoa. While one party searched for the missing Ochoa another pursued the herd south over the mesas, recovering all but a dozen or so animals. Around four that afternoon Ignacio Orosco came in with a grisly trophy and a grislier story. He had found two corpses on the mesa opposite Agua Fría. The fresh scalp he had taken from one of them the tame Apaches identified as that of Nagayé, capitancillo and feared warrior. Ochoa had managed to cut the ties Nagayé had bound him with and had stabbed the Apache to death with a hunting knife. He would have got away had the other hostiles not surprised him just then. So thoroughly had they mutilated Ochoa's body that it could not be brought in to Tumacácori for burial. Nagayé the tame Apaches "hung on a stake, as they say." Because of the signs of hostiles all round, López ordered a corral built inside the mission. On moonlit nights the horses would be driven in to protect them from the marauders. In closing he told how a settler on his way from San Ignacio had run into two Apaches. "If he had not been on a good animal he too would have perished at their hands." [15] In less than a month, on January 5, 1830, Apaches attacked the mission vaqueros at Calabazas. Just then the detail carrying the monthly mail from the presidio of Tucson rode up. Together soldiers and vaqueros fought off the hostiles and retreated with the horse herd to Tumacácori. Denied a single horse, the Apaches returned to Calabazas where "they set afire its buildings and chapel, carrying off all of the sacred vessels and vestments from the latter." [16] Though they continued to run stock in the area, no one felt safe anymore at Calabazas. But for the presidio of Tubac, the declining mission of Tumacácori would surely not have survived. More than five hundred persons still lived in and around Tubac. A census of settlers, apparently compiled in the 1830s, showed 201 adults and 105 children, not counting members of the garrison or their dependents. Second-generation tubaquense don Atanasio Otero and his family led off the list, followed by several other families whose heads deserved to be addressed as don and doña: José Sosa, Tomás Ortiz, Pedro Quijada, and doña Reyes Peña, widow of don Agustín Ortiz. Though people still called the Tubac garrison the Compañía de Pimas it probably by now included more mixed-breeds than Pimas. Carried on the rolls at headquarters in the late 1820s with three officers and eighty-one men, they rarely mustered at full strength. [17] For a time in 1832 in fact it seemed as though Tubac would be abandoned. The military had been using every means available to wage a defensive war against the Apaches: forced levies of Indian auxiliaries, confiscation of animals and stores, volunteer companies of settlers, appeals to patriotism, semi-private treaties with willing Apache bands. They had divided the embattled frontier into two sections, the first composed of the companies of Fronteras, Bavispe, and Bacoachi; and the second of Santa Cruz, Tubac, and Tucson. Still the enemy ran wild. In May, 1832, all the officials of nine "patriotic pueblos"—Cucurpe, Tuape, San Ignacio, Magdalena, Ímuris, Cocóspera, Tumacácori, San Xavier del Bac, and Tucson—gathered as guests of Fray Rafael Díaz at Cocóspera to form a third section, La Sección Patriótica. First they elected don Ignacio Elías to preside over the meeting, then named don Joaquín Vicente Elías chief of the organization and drew up articles. Father Díaz signed the pact "for himself and for Francisco Carros, 'Lieutenant General of the Pima Nation.'" They would march for Tucson the next day to rendezvous for a campaign. They would kill some Apaches. [18] At four in the afternoon on May 23 the irregular column marched into Tubac. There Jefe Joaquín Elías saluted Lieutenant Antonio Comadurán of Tucson, commander of the Second Section, who had just that morning attacked the enemy in the Sierra de Santa Rita. Because of spent horses Comadurán had given up the chase. Elías volunteered. Commanding fifty horsemen and as many on foot he departed at once and for several long days kept on the trail. When it became obvious that the Apaches were in full flight, he returned to Tucson for the rendezvous. There a note from Commandant General José María Elías González called into question certain of the Sección Patriótica's basic articles. It was too late. They had resolved to act. At the head of some two hundred motley volunteers, Elías set out again, this time destined for combat. Operating fifty miles or so northeast of Tucson on June 4, 1832, the Secció Patriótica trapped a large gathering of Apaches, mostly runaways from the peace camps at Tucson and Santa Cruz, come together to celebrate an alliance with Capitancillo Chiquito and twenty-five of his braves. After a four-hour battle in the Cajón de Arivaipa the jubilant Mexicans claimed a count of seventy one braves killed, thirteen children taken captive, and 216 horses and mules seized. Elías let those who caught them keep the Apache children. The branded animals he returned to their owners, the rest he distributed among his men, except for the three mules he gave to the widow of Roque Somosa, the only Mexican killed. Twelve suffered wounds. Reporting his triumph to the commandant general, Jefe Elías begged him to forgive the Sección Patriótic a for going ahead. If they had done wrong, it was all because of his ignorance of military procedure. [19]

News of the signal victory of Joaquín Vicente Elías and his irregulars evoked mixed responses. Many feared bloody Apache retaliation. "Now we'll have them in our homes," wrote San Ignacio's justice of the peace, imploring Governor Escalante y Arvizu to send twenty-five muskets and ammunition. The governor dispatched word of the triumph, "in a nutshell for time does not permit more," to his counterpart in Chihuahua where it was published. Sonora's governor said he had taken what measures he could to head off retaliation by the barbarians: he suggested that the governor of Chihuahua do the same. [20] Officers of the regular military, who had of late fired more rounds at one another than at the enemy, understandably resented the success of a bunch of farmers and breeds. Something else worried Antonio Comadurán:

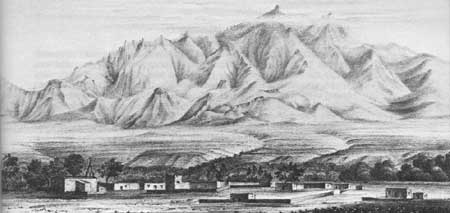

He feared an alliance with the enemy. [21] One officer and politician, don Ignacio Zúñiga, native of Tucson and son of its former captain José de Zúñiga, delighted in the Elías victory. In his Rápida ojeada, published in 1835, he wrote:

He cited other victories by the citizens of Tucson and by the Gila Pimas. For the regular frontier military Zúñiga had nothing but scorn. [22] Now and again over the next quarter-century there would be occasional Mexican victories like Elías' to relieve the dreary reports of Apache depredation and killing. More typical of life in Hispanic Arizona during the 1830s and 1840s was the gnawing fear and the pressure of constant guerrilla warfare. Just six days after the patriots' triumph, Tubac Justice of the Peace Trinidad Irigoyen lamented the condition to which they had to return. Tubac that summer was as usual virtually unmanned. The garrison had been called to duty in the south where a series of barracks revolts had further split Sonora's military. The settlers were terrified and many had fled. Told to requisition ten men from Ímuris, Tubac commandant José María Villaescusa, younger brother of Pedro, got a note in reply saying that no one in Ímuris had a horse or weapons. "I am being left alone," he complained, "with the three retired soldiers and one aide, and with the soldiers' families." The rest of the settlers, who had remained only to look after their wheat, were on the verge of abandoning their homes. As evidence of his plight Villaescusa sent the letter of Trinidad Irigoyen on to headquarters. "Today," Irigoyen had written,

Within a month a ragtag militia company of twenty-four "cívicos auxiliares" from Oposura, recruited for short-term service at Tucson, arrived instead at Tubac with their sergeant Juli&aacut;en Zubía. Comadurán figured that depopulated Tubac needed them more than Tucson.

Seven deserted almost immediately. The rest of these poor, unpaid, demoralized men, still at Tubac in October, wanted more than anything else to go home. "These people," wrote Zubía, "are unfit to render any service active or passive because of the nakedness they suffer." [24] Headquarters recognized the need to restore a regular garrison to Tubac and to relieve the unfortunate reserves. In 1833, with the Yaquis and the insurgents more or less under control to the south, the soldiers returned and with them some of the settlers. A year later, on the fourth of July 1834, Juan Bautista Elías, Tubac's justice of the peace, pleaded with the governor. Things were as bad as ever. Worse. A note to Tubac commandant Salvador Moraga, written in Tucson the day before, warned of an impending Apache onslaught. According to a woman captive, who had just escaped from the Sierra de Chiricahua on a fast horse, the barbarians' immediate target was Tubac. If they came, said Elías, it would take them only a few hours to utterly destroy the place.

There was not a single piece of artillery at Tubac. The few settlers were poorly armed. The garrison, if the paymaster got back in time, could hardly muster ten or a dozen men. Unlike Tucson or Santa Cruz—with their walls, artillery, hundreds of settlers, and regular forces of troops—isolated, defenseless Tubac lay at the Apaches' mercy. As poor men, the settlers of Tubac had to go out themselves every day to work their fields and tend their animals. In doing so they took their lives, and those of their families, in their hands. Elías begged the governor to intercede with the commandant general. They had asked before. If additional troops were not assigned to Tubac, the settlers were again resolved to evacuate the place, "even though the little we possess is lost." Life was dearer. [25] Fray Rafael Díaz had had it with Pimería Alta. He wanted a transfer to New Mexico. When that failed, he resigned himself. Obviously he could not be everywhere at once. He chose to reside at Cocóspera and ride the circuit down the river from the presidio of Santa Cruz to the presidio of Tucson, a hundred mile stretch along which any clump of mesquite trees or any arroyo might conceal an ambush. Whenever he was well and could get an escort, coming and going, he stopped at Tumacácori. Because the lands belonged to them, and because it was home, some Indian families hung on at the mission despite drought, famine, and Apaches. Father Díaz had described their plight to the vice governor on November 1, 1832. The drought of that year, the friar averred, was "so complete that we have not raised a grain from a single seed." Most of the Indians had no stores to fall back on, so they sought jobs away from the pueblo, at which they earned only two reales a day—barely enough to feed themselves—while their families "are subject to perish without the least help." Starvation was only one problem. "There is more," Díaz lamented. The defense of Cocóspera and Tumacácori sorely perplexed the Franciscan. The presidial forces of Santa Cruz and Tucson had ignored their urgent calls for help. Three Apaches alone had stolen seven bunches of horses from Tumacácori. "Help was requested but it was refused us." When Apaches murdered two women and two little girls and abducted three other girls only half a league from Cocóspera, a plea to the commander at Santa Cruz had brought not even the courtesy of a reply. "Is it possible," the friar asked, "that they will order us to dismember the slim force we depend on so that our people must look after the garrison of Tubac?" He prayed God that the government would not order what the two pueblos could not possibly obey. To discourage the plan, he appended lists of the twenty-nine males of Cocóspera and the eighteen at Tumacácori.

"These reasons," the missionary concluded, "and the impotence to which we are reduced seem to us sufficient to exempt us from a burden that is intolerable to us. Nevertheless, if Your Excellency does not consider them sufficient, let us know whatever your superior pleasure is and we shall give it our serious consideration." [26] To oversee what mission temporalities were left at Tumacácori, Father Díaz commissioned don José Sosa of Tubac. Sosa's father, the long-deceased Ensign José María Sosa, had served at the presidios of Tubac and Tucson. When young José had asked for the hand of Gregoria Luz Núñez back in 1811 he had to obtain a dispensation from the bishop: he had known his intended's sister carnally before he proposed. [27] Twenty years later don José and doña Gregoria presided over a large family at Tubac. But to the Indians of Tumacácori, Sosa was a no-good white. In 1833 they accused him of embezzlement and of "other offenses no less serious" and carried their complaints to the governor. Because Tumacácori was subject to its neighbor in civil matters the governor's office charged the Tubac authorities newly elected in January, 1834, to hear testimony regarding the bad or good conduct of don José Sosa. Justice of the Peace Juan Bautista Elías complied. As scribe he named José Grijalva and as corroborating witnesses Pablo Contreras and Nicolás Herreros, son and heir to León Herreros. He called six witnesses, none of them Indians. Only two knew how to sign. Their testimony, though not conclusive in the matter of José Sosa, did expose the strained relations between the Indians of Tumacácori and local settlers. The first witness, José Antonio Figueroa, resident at Tumacácori, appeared before Elías on Friday, January 24, 1834. Forty-four years old, illiterate, listed on the Tubac census with his wife and three children, Figueroa said he did not know whether Sosa's conduct had been bad or good. Asked if Sosa had misappropriated anything belonging to the mission, or if because of him some of the Indians had fled to the villages of the heathens, he again claimed ignorance. He did know that certain Tumacácori Indians had disappeared from the pueblo, but he had no idea why. Four of them had broken out of the Tubac jail where they were being held for indictment in the murder of a soldier. When one of the suspects had dug up the body from where they had buried it, Figueroa and two soldiers took custody of it and returned it to Tubac. Had Sosa or any member of his family insulted or harmed the mission Indians? That Figueroa did not know either. The same day Elías called Tiburcio Campa, married and the father of five. In his opinion don José Sosa was an honest man. "Of the six Indians whom the agents of the accused had charged," said Campa, the four who killed the soldier had fled jail. He mentioned two others who left Tumacácori, for what reason he did not know. The question of abuse of the Indians by Sosa he answered indirectly. A compadre of his, one Guadalupe Canelo, had related an incident at the rancho of Calabazas involving Sosa and Ignacio Pamplona, son of Ramón. The mission administrator had evidently given the Indian a severe tongue-lashing. Pamplona had said not a word in reply, just took the reins of his mule and returned to Tumacácori. That was all Campa could say. He signed his name. To get to the bottom of the incident at Calabazas, Judge Elías summoned Guadalupe Canelo, thirty-five years old and illiterate. He had been present. Pamplona had arrived at Calabazas to brand some animals belonging to the mission. Sosa did not give him a chance. The Indian suffered the administrator's abuse without a word and went back to Tumacácori. As for the six Indians who fled, Canelo thought Father Díaz' report would clarify the matter. Thirty-four-year-old Julián Osorio, a resident of Tumacácori, began by affirming the honesty of the accused, then proceeded to cast aspersions. Sosa had at pasture a flock of a hundred sheep, most of them marked with his brand but vented with the mission's. The witness did not know how Sosa had come by them, unless he had taken them as payment for his work. He had heard Sosa say to don Esteban Velos, who had the wool weaving concession at Tumacácori, that with what was wasted at the convento through carelessness alone a man could support himself. When asked if Sosa abused the Indians, Osorio responded "that the Indians themselves had told him so." And he believed it, especially after Sosa mentioned his quarrel with Pamplona. In closing Osorio told how a delegation of Indians had called on don Ignacio Ortiz and noticed in his house a trunk belonging to the mission. Don Ignacio explained that Sosa had sent it. When Ortiz asked if they wished to take it, they had demurred. With that, Osorio made his mark and stepped down. The fifth witness, don Esteban Velos, age fifty-five, denied categorically as a Catholic Christian the conversation alleged by Osorio. Literate, thirty-three-year-old don Ignacio Ortiz, sixth and final witness, did not deny the presence of the trunk. The Indians had suspected that his brother don Tomás had removed it from Tumacácori during his term as administrator. But don Ignacio disabused them, explaining that his compadre Sosa had merely left it with him for safekeeping. That concluded the testimony, which Justice of the Peace Elías duly submitted to Arizpe. The verdict, if any, is missing. [28] A couple of years later Sosa appeared before Justice of the Peace Atanasio Otero to press his right to more water: the mission fields and diversions upriver were taking it all. He petitioned Otero or persons designated by him to come look at his wheat field. On investigation deputy Pablo Contreras noted that Tumacácori's wheat needed irrigation more than Sosa's. "It was from laziness not a lack of water that there were dry places that had not tasted a drop since planting." When a flash flood, unusual in May, washed down the river, there was suddenly an abundance of water. After the mission's wheat and that of an individual Indian had been irrigated, Sosa would get his share. [29] Conditions in the moribund missions of Pimería Alta did not improve. Settlers opposed Father President Pérez Llera at every turn. First they put some Indians of Caborca up to asking the governor for full citizenship, distribution of mission lands, and an end to the friars' paternalistic rule. The governor, fearing an uprising if he denied them, consented, in vague terms, thereby overturning the law Pérez Llera had secured in 1831 and confusing the status of Indians and friars alike. Everyone could see the weakness of the government and how little laws mattered. When the Father President despaired of ever receiving the traditional mission subsidy and tried to collect from every settler on mission lands a minimal annual tribute of one fanega of wheat or a calf, even a peso and a half or two—a system used previously at San Xavier and Sáric—they almost threw him out. "Already considering themselves owners of the lands, even this trifle seemed to them intolerable." In 1832 the four Franciscans—Pérez Llera, Díaz, Maldonado, and Faustino González—had met at Magdalena to discuss strategy and to dedicate the church that Pérez Llera had built. Obviously they had to have help. If they recruited a few more friars perhaps they could then set up a school to train youths to assist them. In hopes, Pérez Llera built three additional rooms at Magdalena and asked for government aid. Then in 1833 he had made the long journey to Querétaro to enlist more missionaries. He found few of his brethren inclined, qualified, and healthy enough. Only two, Fray Ángel de la Concepción Arroyo and Fray Antonio González, returned with him. At San Ignacio he had an answer from the government: the treasury was bare. So he assigned the two new arrivals, evidently Arroyo to Caborca and Antonio González to San Xavier, and busied himself with church building at Ímuris and Santa Ana. "But while I was trying to build, the government was doing nothing but tearing down. With the change of systems and regimes, decrees were issued one after another, sometimes contradictory, and without repealing the conflicting sections of earlier ones." The Father President was torn, "sick of being a sorrowful spectator of turmoil I could do nothing about." He wanted to get out. He had served his decade in the missions, he had suffered more abuse than he thought he could stand, and he knew now that neither the government of Sonora nor his own college could help. Yet how could he abandon these wretched souls? He would make one last effort. Leaving sealed instructions for old Faustino González to take over as president, Pérez Llera sneaked away from San Ignacio one day in January, 1837. A strong, conservative, pro-Church faction had come to power in Mexico City. By the new constitution of 1836 this regime sought to save Mexico from federalism by an abrupt return to centralism. It decreed an end to the chaotic, nearly autonomous state governments and substituted a system of departments whose governors were appointed from Mexico City. Father Pérez Llera would carry an appeal to the president of Mexico. After only a few days' rest at the college, which he reached in June, 1837, Pérez Llera rode on to the capital. President Anastasio Bustamante granted him an audience, as much to learn what the friar had to say about politics in the Department of Sonora as to hear him out on frontier missions. Father Pérez proposed to the president that a board of experienced missionaries be named to advise the government on means of preserving and advancing the missions. While in Mexico City the Franciscan also called on the bishop-elect of Sonora, Doctor Lázaro de la Garza y Ballesteros. He wanted to brief the prelate on missionary matters and make certain recommendations. Soon after Pérez Llera returned to Querétaro, bad news reached him from Sonora. [30] Two days after Christmas, 1837, Comandante Militar José Urrea, son of don Mariano and native of Tucson, who began his military career at Tubac in 1809, had pronounced against the central government and called for a return to federalism. A week later the wily criollo lawyer appointed by President Bustamante governor of the Department, don Manuel María Gándara, cast his lot with Urrea and the revolt. When centralist forces did not disperse promptly, Gándara switched sides again. Henceforth for a generation the factions of the opportunist Gándara and his opponents would keep Sonora embroiled in brutal, internecine civil wars. In the fighting would die all hope for the missions. [31] In 1836, just before the furtive departure of Father President Pérez Llera, the missionary roster apparently looked like this:

Within five years only two were left. Juan Maldonado soon took his leave of the Altar Valley to rejoin the Jalisco province, laboring on in central Sonora until they buried him there in the church at Opodepe June 13, 1852. To replace him, Antonio González transferred down to Oquitoa late in 1837, presumably from San Xavier-Tucson. That same year Rafael Díaz had moved southwest from Cocóspera to San Ignacio to fill in for Pérez Llera, who never returned to the frontier. From 1837 until his death in 1841, Father Díaz was pastor to the entire northern Pimería, from the mission of San Ignacio to the presidio of Tucson, which meant that the poor remnant of Pimas and Pápagos at Tumacácori rarely saw a priest. [32] Time was running out for the Queretaran friars. In 1839, the year before he died, the venerable Fray Faustino González, Father President and comisario prefecto of missions, wrote one last plea to the government, to Governor Gándara. Much of what he said, Father President Mariano Buena y Alcalde had said seventy years before. Because of the circumstances of these unsettled times, wrote González, the remaining mission Indians wallowed in misery, vice, and ignorance of God, utterly insubordinate to their ministers. Mission property existed in name only, in "hopeless disorder, for everything pertaining to the fields and lands is up for grabs to all." Thus the economic base of the missionaries' spiritual ministry had crumbled. Father Pérez Llera had struggled for years to restore traditional administration in the missions. He had carried his cause to Mexico City. Just when it appeared that the national government would set everything right, the Urrea revolt threw the pueblos into worse confusion. The Father President had a plan for the times. The college obviously could no longer cope with the situation in most of Pimería Alta. Of the four missionaries in the field, he himself because of illness and age counted for naught, and two of the others begged for licenses to return to Querétaro. The Indians, since 1812 denied the benefit of the true and apostolic way in the missions, had dispersed. "In these past ten years that they have lived unrestrained," González asserted, "many have died because they left that more ordered life, others are now married to gente de razón, while still others are drifting about or in the employ of gente de razón." Even the Pápagos who had been congregating in the western missions, since the discovery in the mid-1830s of gold placers near Quitovac and elsewhere in the Papaguería, were now mixed with gente de razón. Given these conditions, there was no hope of turning back the clock. Instead, Father President González wanted to hand over to the bishop all the missions but San Xavier del Bac. He had already figured out how to arrange the parishes: (1) Caborca and the placers; (2) Altar and all the settlements upriver to Tubutama; and (3) the San Ignacio district and Coóspera, with an assistant for Santa Cruz, Tumacácori, and Tubac. He would also name competent and trustworthy citizens as sort of economic overseers of the Indians, one at Caborca and one at Altar. Freed of this tremendous burden the remaining Queretarans could go back to propagating the faith. With a friar at San Xavier, "I believe," González ventured, "that Father Guardian José María [Pérez Llera] will come with another zealous Father and found a mission on the Gila." Even the fierce Apache and the Yuma of the Colorado might then be induced to come in and settle down to the civilized life. [33] It was the friars' last offer. Meanwhile, five hundred miles south, Bishop Lázaro de la Garza had settled into the episcopal palace in Culiacán. He was a rigid prelate and, in Father Pérez Llera's opinion, not sufficiently informed about the missions or distant Pimería Alta. When someone reported to him that Queretaran missionary Antonio González had allegedly abused the privilege of administering confirmation, the bishop forthwith retracted "the faculties of dispensing impediments to marriage, of administering the sacrament of confirmation, and all the faculties of missionaries, reserving them only to the Father President." [34] That precipitated a crisis and gave the college an excuse to get out of the missions. The long-suffering Faustino González died at Pitiquito in 1840. At the college Father Pérez Llera, elected guardian by his few remaining brothers, wrote a four-page eulogy in the death register. He recounted how González had been sent to the missions in 1805, how he had finished the grand church and convento at Caborca, how the people of Cieneguilla had refused to let him be expelled in 1828. He praised Fray Faustino's heroic deeds, the remarkable fruits of his ministry, his chastity, and his exemplary and utter poverty. Padre Faustino had used the same saddle for thirty years. [35]

Pérez Llera named Fray Rafael Díaz, senior man in the field, the new Father President, a hollow honor at this stage. In a wobbly hand Díaz announced his appointment to Antonio González at Oquitoa and to Ángel Arroyo at Caborca, and at the same time informed them that the bishop had stripped them of their faculties. But Father Díaz, the last Spaniard, had taken to his bed. Not yet forty-seven, he died in the summer of 1841. Temporarily González and Arroyo put themselves under obedience to Fray Antonio Flores of the Jalisco province, resident at Opodepe, sixty miles south of San Ignacio. González moved over from Oquitoa to live at San Ignacio, and Arroyo left Caborca for the Altar Valley. Now they were only two: Arroyo for the western Pimería, González for the north. [36] A native of Salamanca in the state of Guanajuato, Fray Antonio González had put on the Franciscan habit at the college in February, 1823, just after Santa Anna pronounced against Emperor Agustín de Iturbide. In the late summer or early fall of 1841 he rode down the Santa Cruz Valley with his escort taking possession at each settlement by formal inventory. He called Tumacácori not San José, its patron for nearly ninety years, but rather La Purísima Concepción, from an image of the Virgin over the main altar. For all that it mattered, Antonio González was now missionary of Tumacácori in absentia and trustee of its lands. [37] In November, 1841, before the surveyor began measuring the so-called Los Nogales de Elías grant, south and west of Tumacácori, he notified Father González. The friar delegated don Marcelo Bonillas to act in the matter and make certain that the new grant did not encroach on the mission's. Bonillas in turn summoned the native governor, Ignacio Pamplona, to point out to the survey crew the landmarks of the mission estancia. Later don Francisco González of Ímuris, one of the Los Nogales grantees, asked Pamplona to loan him the Tumacácori land documents so he could "learn the boundaries." That was the last the Indians ever saw of them. [38] Bishop Lázaro did not want the missions of Pimería Alta, at least not just yet. He had explained to Father Guardian Pérez Llera why he had taken back the missionaries' faculties: it was a matter of maintaining the purity of the sacraments. He did not want the missionaries to leave. In fact he had told the government that the diocese could not possibly take over the missions immediately. The bishop had not a priest to spare. He begged the Father Guardian to keep his friars in the field for four to six years more. By then the bishop would have ordained some graduates of the seminary he had founded in Culiacan. Then, he told the Franciscan, "I shall grant you, if it pleases God, the favor you desire." [39] Father Pérez Llera would have none of it. He had made up his mind. At this point he did not want the dying missions either. The recommendations he had made in 1837 had been ignored and his dire predictions realized—the missions were ruined. Though he deeply regretted giving up Pimería Alta at a time when the diocese was suffering a shortage of secular priests, the college had no alternative. The Father Guardian feared for the pitifully undermanned college. Reduced to a mere handful of friars, a target for suppression by the anti-clerical element, the college could no longer hope to maintain a missionary field. Since there was now no chance of sending compañeros to the last two missionaries, Pérez Llera intended to consolidate the community at the college. "I can do nothing," he wrote to the bishop late in December 1841, "but proceed with my decision that they be recalled." [40] Sometime in mid-1842 González and Arroyo left Pimería Alta. After seventy-five years, the missionary college of La Santa Cruz de Querétaro had terminated its ministry to the Pimas and Pápagos. The two friars did not retreat to Querétaro immediately. They reported to Jaliscan Fray Antonio Flores at Opodepe. Behind them, the settlers on the Río Magdalena, some of whom had taken every advantage of the missionaries in their recent troubles, cried out for the grayrobes to come back. The justice of the peace of Magdalena, speaking for at least four other justices, begged Flores to let González return. He bewailed

Fray Antonio González did come back to San Ignacio, a son not of the college of Querétaro but of the Jalisco province. Now his assignment was even more hopeless. During 1843 he rode not only the northern circuit but the Altar Valley as well. So vast was his territory that he appealed to the bishop to relax the required announcement of the marriage banns at Mass on three successive feast days: most of the Pimería was now without Mass. Their fear of roaming Apaches and their poverty made it impossible for the people to get to San Ignacio. On his occasional visits to the scattered sheep of his flock Padre Antonio had to marry, baptize, sign the burial entries since the last time, and move on. Because of hostile Indians and bandits the friar always took an escort, as many men as he could muster. Whenever he could he joined columns of soldiers. On February 7, 1843, he reined up at Tubac en route from Tucson with Captain Antonio Comadurán, a corporal and eight soldiers, four Apache auxiliaries, and the four settlers serving as his personal bodyguard. The entire party departed the following day. [42] Little had changed at Tubac. Monthly reports from the garrison amounted to routine composites of woe. On November 1, 1842, the one-hundred-man infantry company had mustered sixty-six soldiers and one corporal short, "for lack of men in this district." Of the thirty-three on the rolls only three were available for immediate duty. The rest were accounted for as follows:

The garrison had not a single pack mule.

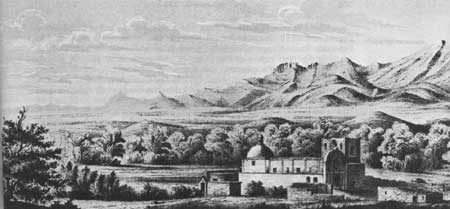

Few officers put in for duty at Tubac. Since the retirement of Lieutenant Salvador Moraga on May 1, 1841, the office of post commander had remained vacant. Lieutenant Roque Ibarra of the Pitic garrison, off on an Apache campaign, commanded ad interim. The position of Ensign Manuel Alarcón, a casualty on February 1, 1838, had still not been filled. Sergeant Jerónimo Errán of Tucson, breveted to ensign, filled in and acted as paymaster. The reports routinely described the presidial barracks as "the property of the Nation, healthful, and deteriorating for want of resources to repair them." The only thing that saved Tubac was the presence outside the presidio of an encampment of Apaches de paz—49 men, 53 women, and 67 children—under Capitancillo Francisco Coyotero. [43] At Tumacácori the physical plant was crumbling. On April 3, 1843, the Tubac justice of the peace filed a report on the sad state of the neighboring mission. He had been ordered to describe in detail any former Jesuit properties, their current status, and the revenue they produced. With Santa Anna ruling as dictator in Mexico City, there was talk, incredible as it must have seemed, of bringing back the Jesuits to restore the frontier. The Society of Jesus had operated no estates in conjunction with Tumacácori, the Tubac official assured his superiors. The buildings of the mission convento, which he dated 1821, were in 1843 "for the most part fallen down and the rest threatening ruin." Only the church held up. The mission's two former communal fields, immediately south of the pueblo and half a league away across the river, since 1828 had lain "unfenced and abandoned, full of mesquite and other bushes." Because of a shortage of water in the river, the few Indians who remained irrigated only their own small fields. Calabazas, Guevavi, and Sonoita were in ruins with neither buildings nor anything else of value: only a few stray cattle roamed the hills. The subprefect of San Ignacio transmitted the justice's report to the proper authorities in Guaymas. [44]

No one knew what would happen on the Sonora frontier in the early 1840s, but most everyone predicted disaster. There seemed to be no way of containing the Apaches. The frontier military could not even wage an effective defensive war. Constantly undermanned, short of everything from lances to saddles, torn by allegiance to one faction or another in the Sonoran civil wars, the presidial garrisons barely survived. The gandaristas appealed to the Indian tribes to fight on their side, which threatened to turn the internal conflict into a race war. Captain Comadurán feared that the aroused Pápagos would attack Tucson. [45] After decades of thrusts, passionately parried by the friars, secularization finally overcame the missions of Pimería Alta, not by any scheme of the reformers, not by the orderly process set forth in the Spanish Laws of the Indies, not by the Mexican decree of April 16, 1834, which was waived on the Sonora frontier, but by default. The Queretarans, protested Bishop Lázaro de la Garza, simply abandoned them, "against my will and without conveying to me the pueblos they were serving." [46] After 1843 the signature of Fray Antonio González, the last of the Franciscans, ceased to appear in the mission registers. In the spring of 1844 don Francisco Javier Vázquez, venerable parish priest at Cieneguilla, compiled for the bishop a brief report on the churches of Pimería Alta. He had visited, reclaimed the priest's quarters, and appointed sacristans in the ex-mission pueblos of the west and those of San Ignacio and Cocóspera. He had ventured no farther north into the territory "occupied by the carnivorous Apaches, sacrilegious murders of Father Andrés [?] and other Fathers." He had heard of "a pueblito called Tumacácori," but he seemed to confuse it with San Xavier. [47] Others too had heard of Tumacácori. They wanted its virtually unpeopled lands for speculation. The Apaches had chased away all but a poor remnant of ignorant Indians who no longer even had possession of their title papers. No missionary would intercede in their behalf. On April 18, 1844, without the Indians' knowledge, the entire Tumacácori grant—fundo legal, estancia, and other lands—was sold at public auction in Guaymas for five hundred pesos. The lone bidder, don Francisco Alejandro Aguilar, just happened to be the brother-in-law and agent of Manuel María Gándara. Based on article 73 of the law of April 17, 1837, and on the decree of February 10, 1842, unclaimed mission lands, whose value did not exceed five hundred pesos, could be sold to help out the impoverished public treasury. The Tumacácori lands had been declared abandoned and valued at five hundred pesos. [48] No matter that Ignacio Pamplona and a few of his kin still lived there. The new owner was in no hurry to evict them. Soon enough the Apaches would take care of that. Once or twice a year between 1844 and 1848 the parish priest from San Ignacio, Bachiller don Trinidad García Rojas, heavily escorted, rode circuit down the Santa Cruz Valley. In the massive church at Tumacácori, beset now at ground level by an army of thirsty mesquite, he celebrated baptisms and marriages for the impoverished Indian remnant. The record of these services, which he entered in the books at San Ignacio, gave the lie to the Aguilar-Gándara claim that the mission was despoblado. No matter. No one consulted Padre García. [49] At Tubac Sergeant Jerónimo Errán, breveted to ensign, took command of the pathetic garrison. He evidently was a son of don Nicolás de la Errán, who had originally moved the Pima infantry company to Tubac in 1787. Although don Jerónimo labored under the most adverse conditions in his first command, no one doubted his personal bravery. Errán happened to be at Tucson in early September, 1844, when Apache scouts reported the fresh tracks of hostile Apaches nearby. Within three hours Comandante Antonio Comadurán swung into the saddle at the head of seventy men—soldiers, settlers, Apaches de paz, and Pimas. Ensign Errán, with the commandant's permission, rode with them. The column skirmished with the enemy and alerted the countryside. Comadurán, in his report, praised "the determination and valor" of Errán, who "grabbing a brave by the hair, freed an Apache manso and killed [the former] with lance thrusts." [50] While their countrymen in Ures, Guaymas, Horcasitas, Hermosillo, and Arizpe denounced and shot at one another, the frontier commanders struggled to maintain some kind of war against hostile Apaches. Late in November, 1845, Comadurán led a force of 155, including a sergeant, a corporal, and twenty-one infantrymen from Tubac, to the Gila. After one sharp engagement with the enemy, in which the Mexicans killed six braves and wounded three, he had to order a retreat because of the uselessness of the cavalry's horses. The hostiles had been killing off the skinny, broken-down, presidial horses. Despite his precautions, Comadurán predicted that few would survive. From tracks along the Gila the Tucson commander concluded that the whole Apacheria was gathering closeby, in the sierras of La Arivaipa, Cerro del Mescal, Pinal, and Agua Caliente. He feared the result, "especially with us reduced to the purely defensive, without being able to pursue them on their incursions, for want of horses." Writing to his superior, friend, and relative José María Elías González, Comadurán spoke for the entire forsaken population of the valley. "I shall be infinitely glad when you are able to pacify the revolution and turn your view toward the frontier." [51] Sonora's treasury was bare. Frontier commanders found themselves without funds to ration their troops. Who could blame hungry men for rioting or deserting? At Tucson, Comadurán called the settlers together and wrung from them a pledge of one hundred fanegas of wheat. They scarcely had more. He appealed to his superiors to deliver the money, two pesos per fanega, at Tucson on time. If not, the people would sell at a better price to merchants from the placers in the Papagueria. No funds arrived. Yet Comadurán had to pay for the garrison's twice-a month wheat ration somehow. He called on don Teodoro Ramírez, local administrator of the government tobacco monopoly. "To prevent disorders" don Teodoro agreed. With money from the monopoly and with cigarettes he paid for eighty-eight fanegas, enough for distribution on December 15, 1845, and January 1, 1846. He was willing, Comadurán reported to his superior, to purchase the remaining twelve fanegas with cigarettes. [52] Ever since New Year's Eve of 1826 when the first three American trappers showed up in Tucson, stray citizens of the United States had been trespassing in Hispanic Arizona. They trapped and traded with the Indians on the Gila, or followed the Gila route back and forth to California. By the mid-1830s they were making Mexican officials nervous. Testifying in Arizpe, Teodoro Ramírez of Tucson had described a fortified settlement built by americanos on the Gila. The first reports had come from Pinal Apaches in July, 1836. To verify it the commandant at Tucson had sent a couple of Apaches de paz. They returned in early August. They claimed to have counted some forty Americans "tending a field of maize." "The casa fortificada was a redoubt where they had positioned a cannon they had brought with them." While the Apaches watched, the foreigners had packed up and left. The following November they had returned, harvested their crop, and disappeared. [53] Mexican officials suspected Americans, men like the infamous James Kirker, of trafficking with Apaches in arms and ammunition. Evidently in 1836 Governor Manuel Escalante y Arvizu had made a deal with one John Johnson, an American who operated on the fringe of the Santa Fe trade in Oposura, to betray the Apache leader Juan José and his band for a price. In the Sierra de las Animas in April, 1836, Johnson invited the unsuspecting Apaches to a feast and blasted them with a concealed cannon full of iron fragments. [54] A few Americans settled down in Pimería Alta. A Señor Money had come to Oquitoa and married a local girl in 1837. During the 1840s his anti-Catholic attitude and his propagation of "the false doctrines of the Protestant philosophers" made him unwelcome. He left for California in 1849. [55] Other Americans, adventurers and cutthroats, the likes of "Captain" John Joel Glanton, turned a handsome profit harvesting Apaches' scalps, not always from Apache heads, for the bounty offered by Sonora. In 1846 the Protestants' armies invaded Mexico. The United States had declared war. New Mexico yielded meekly. General Stephen Watts Kearny and his Army of the West rode on down the Gila in November bound for California, passing only three days north of Tucson. The battalion of Mormon infantry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, marched farther south to open a wagon road west. They meant to see Tucson.

In an effort to avoid unnecessary hostilities, and because he was outnumbered, Commandant Comadurán sent an appeal to Cooke asking that the Americans detour around Tucson. Cooke refused, and on December 17, 1846, the Mormons entered the presidio unopposed. Comadurán, the garrison, and most of the people had withdrawn a safe distance. Before moving on, Cooke wrote a letter to Governor Gándara. Sonora's destiny lay with the United States. Such a union, he claimed, "is necessary effectually to subdue these Parthian Apaches." [56] The Yankees, most Mexicans believed, were intent on enlisting rather than subduing the bloody Apaches. In April, 1847, don Francisco Javier Vázques, enduring priest of Cieneguilla, told how dangerous travel was because of these American-incited bands of predators. "They are wont to appear in a group of two to five hundred, outfitted and armed with rifles that we know are supplied by the Anglos who have definitely been seen among the Apaches." [57] The presidials were no match. In May of the following year at a water-hole called Las Mesteñas, Apaches cut down fifteen Tucson soldiers. It was two months before their bodies were brought in for burial. Their widows petitioned the commandant general for relief. [58] Late in October, 1848, months after the United States and Mexico had agreed on terms of peace, a column of U.S. Army dragoons commanded by the usually drunk Major Lawrence P. Graham rode down the river from Santa Cruz to Tucson en route to California. Lt. Cave J. Couts, an observant and proper gentleman, noted his impressions.

Evidently their day did come the following year, 1849. They broke and never returned. For a decade and a half no one of record worked these old mines. Then in July of 1864 W. Claude Jones, H. M. C. Ward, and Manuel Gándara filed notice in the First Judical District, Territory of Arizona, that they had "reopened the old Gold Mines of Huevavi... lying in the mountains one half a mile more or less south of the ancient mission." They desired to run arrastras and to work "both the old shafts of the Yaqui Mine and the Huevavi Mine to which end they pray that the same may be registered and denounced to their use and benefit in accordance with the Ordinances de Minería in force in Arizona as said mine has been wholly abandoned since the year 1849." Only days before, Gándara had conveyed the Guevavi lands to attorney Jones as his fee for pressing the Mexican's claim to Tumacácori and Calabazas. On August I, 1864, Jones bid alone for

As the U.S. dragoons proceeded up the valley that October of 1848 Lieutenant Couts studied the countryside. Feed for the horses was scarce. The maize the battalion had bought at Santa Cruz saved the day. A month earlier, Couts reckoned, the grazing would have been good as far as Guevavi, but frost had destroyed it. "From Goibabi to Tucson it is never good, being mesquite growth and chapparal [sic]." He commented on the pumpkins "of a most elegant quality and size" and the not-so-good melons, on the river's sandy bottom, and its disappearance near Tubac.

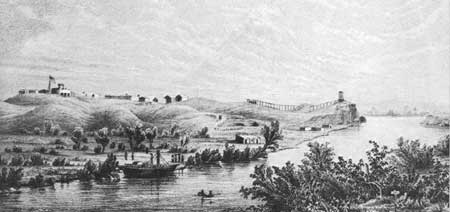

At Tubac, where a recent census had the population at 248, Lieutenant Couts enjoyed a harangue by an Apache "general."

Two months later, in December, 1848, Apaches of a different persuasion devastated Tubac. They plundered and burned and killed, intent on making good earlier boasts. This time they were after more than livestock. And they would be back. The stunned survivors, convinced that they could not hold out and scared for their families, packed what they could, formed up a ragged refugee train, and headed north to Tucson. The Indians at Tumacácori no more than twenty-five or thirty, took down the santos from their niches in the church, bundled up vestments and sacred vessels, and followed the retreating settlers down the road to San Xavier. To add to their suffering that winter, it was colder than any of them could remember and snow blew across the desert. Come spring they hoped to return. To the south a delegate rose in the state legislature and proposed that an urgent appeal be addressed to the national, government setting forth "the condition of the state because of the depredations of the barbarous Apache" and imploring "the most energetic and forceful measures to put a prompt end to so many outrages." In support of his motion the delegate read from recent dispatches sent by the military commandant to the minister of war "telling of the low morale of the troops of his command, of the depopulation suffered by the presidio of Tubac and other pueblos of the state because of the latter's present lack of resources." [62] By the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, everything—including Apaches—north of the Gila now belonged to the United States. Article XI bound the new owners to control Indian raids into Mexican territory, an utterly impossible provision. If anything, the raiding intensified. In April, 1849, the same month the United States appointed a subagent for the Gila tribes, the legislature of Sonora considered a plea by the residents of the Santa Cruz Valley for protection. The deputies, displaying all the confidence of the treaty makers, authorized the prompt dispatch of fifty muskets with ammunition "so that the citizens of Santa Cruz, Tubac [abandoned], and Tucson might arm themselves proportionately and see to their defense against the enemy Apaches." [63] At the same time thousands of sonorenses left for the gold fields of California, "not so much," said one official, "in hopes of bettering their lot, but in search of the security they lack here." [64] As each potential defender abandoned his jacal or rancho the Apache peril grew in proportion. By February, 1849, the towns of the western Pimería were reduced to families of women. The deplorable desolation of Cieneguilla, along with "the frequent incursions of the carnivorous Apaches," convinced old Father Francisco Javier Vázques in May that he should move over to Altar. Unfortunately he did not move fast enough. [65] Others preyed on the desolation. Early Sunday morning, June 3, a hell-bent party of American transients, estimated at forty, burst into sleeping Cieneguilla. Dragging the elderly Padre Vázquez from his home, they put a rope around his neck, led him about like a dog, and nearly killed him. They locked up the rest of the people and proceeded to sack the all-but-deserted town. When they rode off they abducted the priest's sister. [66] Tens of thousands of forty-niners traveled Cooke's wagon road across Mexican territory to California, reinforcing the idea that this strip of northern Chihuahua and Sonora must become the property of the United States and the route of a transcontinental railroad. Instead of bearing north along the San Pedro as Cooke had, party after party chose to ride on to Santa Cruz for provisions, then north down the deserted Santa Cruz Valley to Tucson and the Gila beyond. [67] Some of the argonauts ate peaches in the orchard at Tumacácori, some carved their initials in the picturesque, crumbling church, some sketched it or wrote about it. H. M. T. Powell, who both sketched and described the deserted mission as it looked in October, 1849, was sure that in its heyday "the monks or priests had every accommodation to make life comfortable, as they usually contrive to do." A couple of months later another traveler commented on the melancholy desolation of the place. By then the church roof had fallen in.

Tubac, wrote Powell, "is a mere pile of tumble-down adobe houses. The church has no roof.. . . It was not worth the trouble of sketching. We found some old military papers in one of the houses. I took 2 or 3 of them and put them into my portfolio as a 'souvenir'" [68] On February 6, 1850, when Antonio Comadurán and nine other citizens of Tucson put their signatures to a petition for a priest, they had not even seen one for a year. For more than a decade there had been no resident clergy man in the Santa Cruz Valley. So dangerous were the roads that the Padre from San Ignacio needed an escort of twenty-five or thirty men to visit them. Bachiller Lorenzo Vázquez of Altar, acting for Vicar Forane Francisco Javier Vázquez, had made a visitation of the valley in January, 1849, just after the refugees had left Tumacácori and Tubac. At Tucson and San Xavier the people had lined up for baptisms, confirmations, confessions, and marriages. [69] In their petition the Tucsonans described the doleful consequences of having no Padre. It was especially bad for the Indians:

The prefect of San Ignacio endorsed the petition and passed it on to Governor José de Aguilar, who also recommended favorable action, forwarding the document to Bishop Garza in Culiacán. [70] The bishop was still bitter. He had not forgiven the Franciscans of the Querétaro college for abandoning Pimería Alta. The province of Jalisco had denied his request for friars. The few remaining Jaliscans were dying off. "Thus it is that almost overnight innumerable pueblos have fallen to me that previously were not the burden of the diocese." Although he recognized the plight of orphaned Tucson and San Xavier he had no priests to send. He counseled patience. The few ministers in the field would simply have to continue riding the circuit as circumstances permitted. [71] At the college of Querétaro they had just buried Fray José María Pérez Llera, "a victim of his ardent zeal." More than any other individual he had fought to maintain the missions of Pimería Alta after the expulsion of the Spaniards. But in the end he had lost. Reluctantly, he had withdrawn the last two Queretarans in 1842, against the bishop's will. Pérez had ended his days a missionary in the Sierra Gorda northeast of Querétaro. The eulogist at the college remembered particularly his years in Pimería Alta, where he had labored "with such great success that I do not hesitate to call him the Apostle of Sonora." [72] In the summer of 1850 when the Commission to Arrange Parishes in Sonora reported back to Bishop Garza, they recommended five for Pimería Alta: San Ignacio, Santa Cruz, Tucson, Altar, and Caborca. Santa Cruz was to include Cocóspera and Tumacácori, described as pueblos with convento, kitchen garden, and mission lands; the haciendas of San Lázaro, Santa Bárbara, Buenavista, San Pedro, Ciénega de Heredia, and Babocómari; the rancho of Cuitaca; the mine of Candelaria; and the tumbled-down presidio of Tubac. The commission estimated the distance from seat of the parish to farthest point at twenty leagues, more than fifty miles; the total population at 1,500 souls. The parish of Tucson, with about a thousand persons, would take in the pueblo of San Agustín de Tucson and the pueblo of San Xavier del Bac "with convento, kitchen garden, extensive lands, and a magnificent church." But still the bishop had no priests. [73] No one wanted to admit that the Sonora mission frontier had died. There was talk of inviting the Franciscan missionary colleges of San Fernando de México or Zacatecas to take up the work left undone by the Queretarans. As late as the spring of 1851 Governor José de Aguilar proclaimed that friars of the Zacatecas college were standing by not only to reoccupy the missions of Pimería Alta but also to found new ones in the Papaguería, on the Gila, and on the Colorado. "These settlements," Aguilar claimed, "would attract many colonists and provide security to that border." [74] Fray Francisco Garcés had said the same thing eighty years before, and Father Kino eighty years before him. It was no secret that the United States wanted all or a great part of Pimería Alta, the territory traversed by Cooke's wagon road. To retain it Mexico grasped at straws. Sonora conceded to a single combine of mining and land speculators, the so-called Compañía Restauradora de las Minas de Arizona, all vacant lands and mines in the state from the thirtieth parallel north to the Gila, an area of 60,000 square miles! Although the national government declared this giant giveaway unconstitutional, it and dozens of other schemes to colonize and develop the region under the Mexican aegis attracted an international potpourri of adventurers and filibusters—Frenchmen, Germans, Swiss, Americans—many on the rebound from California. [75] On paper Mexico dotted her vulnerable northern borderlands with military colonies. [76] By 1851 Tucson and Santa Cruz wore the designation but had little else to show. In May a lone Franciscan, one Fray Bernardino Pacheco, received from the vicar forane of Hermosillo his appointment as chaplain of the military colony at Santa Cruz. In addition to soldiers he was empowered to minister to the civilians of Cocóspera, Tumacácori, Tubac, San Xavier del Bac, and Tucson. [77] But even nature conspired against the colonizers. The same month a ghastly plague of cholera, "the black vomit," raced through Sonora, killing in four weeks in the parish of Altar alone 1,116 persons. [78] That summer Lieutenant Colonel José María Flores, commandant general of Sonora, personally led the forces of the military colonies and the National Guard—apparently the same old presidials and settlers under new names—to the Gila where they saw action against both Apaches and Americans. Flores yielded command to General Miguel Blanco de Estrada, whom United States Boundary Commissioner John Russell Bartlett met at Tucson in July, 1852. Although Bartlett could comment then on the depopulation of the valley between Santa Cruz and Tucson, eight or ten months later both Tubac and Calabazas revived. Plans were already afoot.

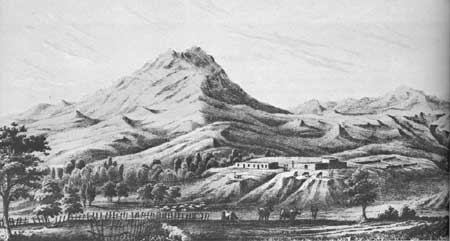

At his hacienda of Topahue in December, 1852—the same month the sixty-five-foot stern-wheeler Uncle Sam steamed up the Colorado River to Fort Yuma—Manuel María Gándara entered into a contract with a group of European expatriates. For a half-interest in "the land called 'Calabazas' situated in the State of Sonora near Tubac" Messrs. Payeken, Hundhausen & Co. agreed to set up and manage a large-scale sheep operation. Gándara further bound himself to stock the land in March and April, 1853, with 5,000 sheep, 1,000 goats, and various other animals at prices stipulated in the contract. Gándara was risking his capital, the managers their lives. [79] Descending Sonoita Creek in April, 1853, surveyor Andrew B. Gray and party reached the fortified hacienda of Calabazas just in time to witness a bloody battle. Sixty mounted presidial lancers and forty Apaches de paz, under Antonio Comadurán and Hilarión García of Tucson, charged into an estimated two hundred Apache hostiles. "The carnage," Peter R. Brady recalled, "was awful." The Mexicans won, as the mutilated enemy head and a string of Apache ears soon testified. Brady at first mistook the ears for dried apples. [80] Under the direction of foreman Friedrich Hulsemann and another German, evidently Karl Hundhausen, laborers had converted the old visita and mission rancho of Calabazas into an extensive walled hacienda. Renovated and partitioned, the ex-Franciscan church became the ranch house. There the two foreigners presided over "their numerous retinue of Mexicans, Pima Indians, and 'tame' Apaches," shared with notable visitors a bottle of mescal, and "kept an awful old 'bachelor hall'." [81]