|

FORT WAGNER

Although black soldiers at Port Hudson and Milliken's Bend had

demonstrated a raw courage and dash that compared with that of the very

best white troops, those fights received such scant coverage and

occurred at such a great distance from the seat of power that they did

not have the impact on the popular mind that many had predicted. Most

northerners in and out of the army needed more convincing. The Union

assault on Fort Wagner provided just such an opportunity.

|

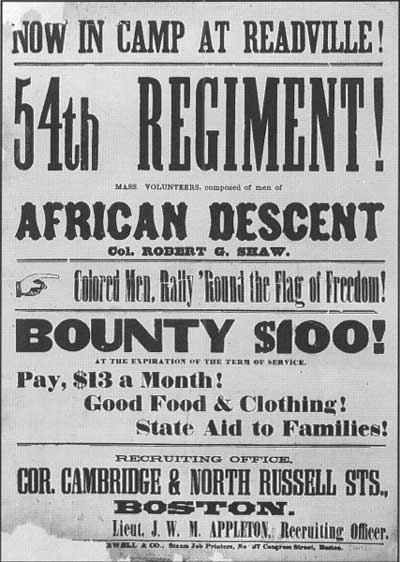

AN 1863 RECRUITMENT POSTER. (MH)

|

Few Civil War regiments attracted the interest of the Northern public

as did the 54th Massachusetts (Colored) Infantry. It was the brainchild

of Massachusetts governor John Andrew and the dream of thousands of

blacks and whites throughout the North. Although it was a state

volunteer regiment, a majority of the men in the 54th Massachusetts

actually came from other states. Prominent African Americans throughout

the North worked vigorously to fill its ranks, as the regiment attracted

some of the finest young black men the free states had to offer,

including two sons of Frederick Douglass.

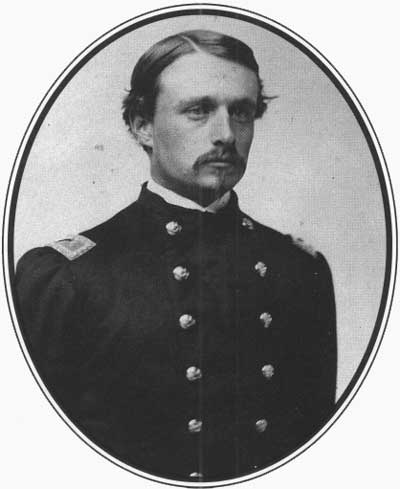

Its officer corps consisted of outstanding young white men. When

Governor Andrew cast around for individuals to command this black

regiment, prior military service and "firm anti-slavery principles" were

mandatory. To locate these men, Andrew searched the educated antislavery

society circles from the prewar years, "which next to the colored race

itself have the greatest interest in the success of this experiment."

From there he plucked Captain Robert Gould Shaw for its colonel and Ned

and Penrose Hallowell as other field officers.

|

COLONEL ROBERT G. SHAW (MH)

|

Andrew received permission to form the 54th Massachusetts at the end

of January 1863, and from that moment a mass of nearly one thousand

black civilians transformed rapidly into a regiment of soldiers. Within

a few' months the ranks filled, and by the end of April authorities

issued the men Enfield rifled muskets. They trained rigorously just

outside Boston, at Readville, and there Andrew presented the regiment

with its flags. With the troops in line and dignitaries in attendance,

Andrew announced to Colonel Shaw, "I know not, Mr. Commander, when, in

all human history, to any given thousand men in arms there has been

committed a work at once so proud, so precious, so full of hope and

glory as the work committed to you." Ten days later they paraded through

Boston as huge crowds lined the streets to cheer. Then they boarded a

steamer bound for the South Carolina coastal islands, and by early June

they were in the war zone.

Before the attack on Fort Wagner, the 54th Massachusetts had gained

limited experience. It participated in a raid on Darien, Georgia, that

resulted in the burning of the town. Even though it was an unwilling

participant in the conflagration, the affair was an embarrassment for

the entire regiment. Shortly afterward, while other Federals slipped

ashore at Morris Island in quest of the prized Fort Wagner, the 54th

Massachusetts helped to lead a feint on adjacent James Island. When

Confederates launched a night attack, men in the 54th Massachusetts held

the line long enough for soldiers in the 10th Connecticut Infantry to

retreat and for reinforcements to advance to the front. As one of the

Connecticut troops penned to his mother, "But for the bravery of three

companies of the Massachusetts Fifty-fourth (colored), our whole

regiment would have been captured. As it was, we had to double-quick in,

to avoid being cut off by the rebel cavalry. They fought like

heroes."

|

A VIEW OF THE INTERIOR OF FORT WAGNER. (MH)

|

Meanwhile, Shaw had been scheming to participate in the upcoming

fight at Fort Wagner. He wrote to Brigadier General George C. Strong, a

West Point graduate from Massachusetts, telling him how much the

officers and men desired a prominent role in the campaign against Fort

Wagner. When Strong's brigade received the assignment to lead the

assault on Fort Wagner, its commander requested the transfer of the 54th

Massachusetts, fresh from its outstanding performance on James Island,

to head the attack.

Although Strong and the officers and men of the 54th Massachusetts

regarded the offer as an honor, division commander Major General Truman

Seymour assented to the request for another reason. The black troops

were expendable. Speaking to operations commander Major General Quincy

A. Gillmore, and overheard by a journalist, Seymour confided, "Well, I

guess we will let Strong lead and put those d—d niggers from

Massachusetts in the advance; we may as well get rid of them one time as

another."

|

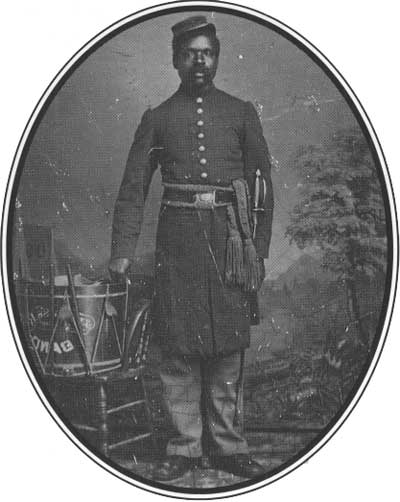

WILLIAM J. NETSON OF THE 54TH MASSACHUSETTS. (MH)

|

Fort Wagner rested near the northern tip of Morris Island. The

bastion was valuable because it protected Battery Gregg, at the very

edge of Morris Island and overlooking the entrance to Charleston Harbor.

With Battery Gregg in Federal hands, they could shell Fort Sumter in the

middle of Charleston Harbor into capitulation, which would close the

harbor completely to Confederate blockade runners and pave the way for

an attack on Charleston.

Seventeen hundred troops and seventeen artillery guns defended the

fort from all directions. They swept the southern approach superbly. For

added insurance, the Confederates had prepared a moat three feet deep

just outside the first wall and a rifle pit two hundred yards beyond

that.

Early in the evening of July 18, the 54th Massachusetts, composed of

630 officers and men, arrived at Strong's headquarters. For much of the

last two days the regiment had been in motion, and the troops had eaten

nothing since breakfast. Nevertheless, Strong merely fed them some words

of encouragement and pushed them forward.

The plan called for the black troops to strike first, succeeded by

regiments from Strong's brigade. In the event these troops did not carry

the works, Seymour had two more brigades to throw into the fight, but he

viewed them as a precaution. The Federal high command anticipated a

swift success. They greatly underestimated the strength of Fort Wagner

and the size of its garrison.

|

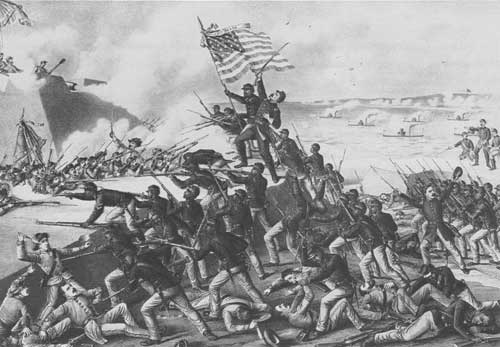

THE ATTACK ON FORT WAGNER. (LC)

|

Shaw planned to have his regiment attack in column in two waves, five

companies across his front. Once they got in position with his right

flank on the edge of the surf, approximately one mile from Fort Wagner,

he had the men lie down to give other regiments a chance to get in

position.

When it appeared that succeeding regiments were nearly in place,

Strong rode up to give some parting words. "Don't fire a musket on the

way up," he warned, "but go in and bayonet them at their guns." He then

asked who was going to carry the regimental flag if the color-bearer

fell, and Shaw, removing a cigar from his clenched teeth, replied

calmly, "I will," to the delight of the men.

As Strong galloped away, Shaw began to wander up and down the lines

and spoke briefly to his troops. In an affectionate tone that surprised

the troops, the soft-spoken commander simply called upon the soldiers of

the 54th Massachusetts that day to "prove themselves as men." Like his

troops, Shaw had a fair inkling of the hazards of the attack. Moments

earlier, he had divested himself of some personal items to a civilian

acquaintance to send to his family in the event of his death.

After a wait that seemed interminable, Shaw cried out, "Boys, are you

ready to take that fort?" Shouts of "Yes! Yes!" resounded as they began

the fateful advance. Shaw elected to lead the left wing personally and

positioned himself next to the regimental flag, while Lieutenant Colonel

Ned Hallowell directed the men on the right.

Confederate batteries on adjacent islands opened fire as soon as they

observed the advance, but the troops at Fort Wagner waited until the

black troops packed tightly into the pocket between the swamp and ocean.

Suddenly, powder flashes lit up the wall and Confederate shot and shell

tore huge gaps in the Federal columns. "Not a man flinched," wrote

survivor Sergeant Major Lewis Douglass, "though it was a trying time. A

shell would explode and clear a space of twenty feet, our men would

close up again."

All the while Confederates poured shot and shell into the rushing

Federal ranks. Yet the black soldiers pushed on intrepidly. Despite

sustaining heavy casualties, they increased speed until they were on a

dead ruin. Through the waist-deep ditch the columns swept, and in

moments the bluecoats clambered up the outer embankment. Some

Confederate troops now came out from their protection and lowered their

aim to strike down the black attackers as they mounted the first

slope.

In the race for the fort, Shaw swung past the salient in the

southeastern corner and drove directly into the center, where

Confederates blazed away at the attackers from three directions.

Positioned at the head of the assault, he miraculously reached the Rebel

works. Witnesses said he had sustained several wounds but refused to

yield. As Shaw reached the top, he urged the men forward, sword swirling

above his head. A ball then crashed into his chest and toppled him

backward dead.

|

THIS PERIOD LITHOGRAPH SHOWS THE STORMING OF FORT WAGNER AND THE FATAL

WOUNDING OF COLONEL SHAW (LC)

|

Despite the loss of the regimental commander, the color-bearer

planted the flag on the parapet and some black soldiers penetrated into

the Confederate works. Thrusting with bayonets and clubbing with rifle

butts, Shaw's troops battled the defenders hand-to-hand. They were no

match for the superior Confederate numbers. Overwhelmed from three

directions, the Federal attackers quickly exhausted their strength and

fell back outside the inner wall. There Confederates began dropping hand

grenades and lighted shells on the assailants.

On the right, Hallowell went down with a severe groin wound, but a

small portion of his men struck the fort in the southeast corner. There

some unnerved Rebels abandoned their defenses, and for a moment it

seemed that the first assault might succeed. Just as suddenly, though,

Confederate reinforcements arrived to drive back the attackers. Had Shaw

concentrated on this portion of the Confederate line, the outcome of the

battle might have been more in doubt, but the Federals here were too few

in number to make a difference.

Nor did Strong's brigade affect the outcome of the battle. His

supporting blue columns were too slow in the attack. By the time they

arrived on the scene, the Confederates had completely repulsed the

assault of the 54th Massachusetts. Their fate was similar to that of

Shaw's regiment, without such severe losses.

Those survivors in the 54th Massachusetts who were able to retreat

began to fall back across ground littered with scores of their black

comrades. The 9th Maine Infantry, whipped into a frenzy in anticipation

of the assault, began pouring lead in the direction of the fort and

felled "a great many" men in the 54th Massachusetts, according to a

black survivor. It took the intervention of some New York troops to

check the friendly fire.

Several hundred yards to the rear, a junior captain took over the

reigns as temporary regimental commander. All he could do was collect

these men and place them in rifle pits where they fired over the bodies

of comrades in support of other Union troops who joined the attack.

As night fell, some men in the 54th Massachusetts crawled away or

bolted across the open ground and managed to return to Federal lines.

One of those men was Sergeant William H. Carney, who snatched the

national flag when its bearer fell and planted it on the Confederate

works. There be sustained a wound in each leg, one in the chest, and

another in the right arm, yet Carney managed to carry the flag back in

retreat.

|

SERGEANT WILLIAM H. CARNEY RECEIVED THE MEDAL OF HONOR FOR HIS

PARTICIPATION IN THE BATTLE OF FORT WAGNER. (USAMHI)

|

|

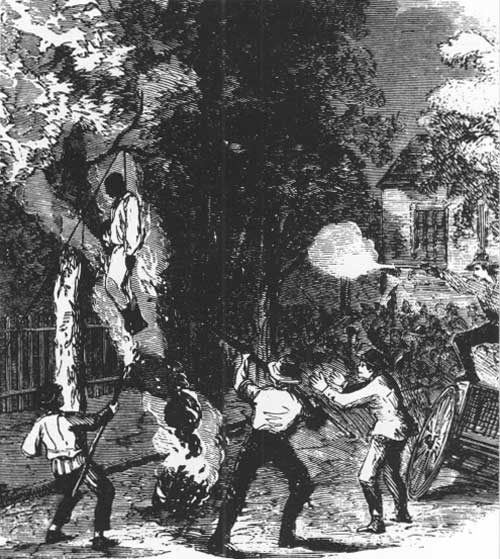

A BLACK MAN IS HANGED IN THE STREETS OF NEW YORK DURING THE DRAFT RIOTS.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

Others who refused to run the gauntlet or had suffered wounds became

prisoners of war. Among them was Sergeant Robert J. Simmons, whose arm

was shattered by a Rebel ball. Unknown to Simmons, three days earlier in

New York City a draft protest had turned into a race riot, and a mob had

terrorized his mother and sister and stoned and clubbed to death his

seven-year-old nephew. In one of the great tragedies of the war Simmons

had his arm amputated and died several weeks later in a Charleston

hospital, representing the very same people who murdered his young

nephew.

Well over 40 percent of the men in

the 54th Massachusetts were casualties in the assault on Fort Wagner. As

one soldier described it, "They mowed us down like grass."

|

Well over 40 percent of the men in the 54th Massachusetts were

casualties in the assault on Fort Wagner. As one soldier described it,

"They mowed us down like grass." Confederate officials sent the wounded

to Charleston hospitals, and after considerable indecision the prisoners

of war went to camps, where some died and others were exchanged.

The Confederates interned the bodies of two officers in separate

graves, but they laid Shaw to rest in a pit with his men. When Union

authorities tried to retrieve his remains under a flag of truce, a

Confederate hollered back indignantly, "We have buried him with his

niggers!" Clearly the Confederates had intended to insult the

sensibilities of whites; instead, it became a rallying cry across the

North and helped to immortalize Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.

One month later, when Shaw's father learned that General Gillmore was

attempting to secure the remains, he requested that his son's body lie

with his men. "We hold that a soldier's most appropriate burial-place is

on the field where he has fallen," the elder Shaw explained.

No doubt, the Battle of Fort Wagner left a lasting mark on its black

participants. Two weeks after the assault, a black sergeant wrote his

company commander, at home recuperating from a wound, "I still feel more

Eager for the struggle than I ever yet have, for I now wish to have

Revenge for our galant Curnel and the spilt blood of our Captin. We

Expect to Plant the Stars and Stripes on the Sity of Charleston." Rather

than undercut their commitment to the cause, the defeat at Fort Wagner

enhanced the desire of the men in the 54th Massachusetts to see the war

through to its successful conclusion. Two months after the valiant

effort of the 54th Massachusetts, the Confederates evacuated Fort

Wagner.

|

PRIVATE ABRAHAM F. BROWN OF THE 54TH MASSACHUSETTS. (MH)

|

In conjunction with the outstanding performance of black soldiers at

Port Hudson and Milliken's Bend, the assault on Fort Wagner challenged

contemporary racial stereotypes. Black soldiers had demonstrated a

willingness to stand up and fight against the Confederacy, something few

Northern whites had considered possible. In turn, this helped to lay the

foundation for the tremendous expansion of the number of black men in

military service over the next two years. Prejudice was too deeply

rooted for the Northern white population to cast it aside, but the

blacks' conduct in these battles impressed them enough to give serious

consideration to the widespread use of black soldiers. Slowly yet

steadily, the Northern public began to warm to the idea that black

soldiers could contribute significantly to the war effort. If the black

troops had misbehaved under fire in these three battles, the results

would have been catastrophic for the black soldiery and the black race.

Fortunately, they fought with the courage of veterans, and that opened

the door for others to serve.

Some eight months after the assault on Fort Wagner, the 20th U.S.

Colored Infantry, raised throughout New York, paraded through the

streets of New York City, the same place where a mob had murdered

Sergeant Simmons's nephew. Now, thousands of people, both white and

black, lined the avenues to cheer these men in Union blue. In part the

draft had made the enlistment of black soldiers more acceptable to

whites because blacks filled manpower quotas as did whites. But there

was more to it than that. Whites had come to realize that these one

thousand black soldiers were fighting for the same government and causes

as were white troops.

|

THE PRESENTATION OF COLORS TO THE 20TH UNITED STATES COLORED INFANTRY IN

NEW YORK CITY. (FW)

|

The change in Northern attitudes, noted the New York Times,

was startling:

Eight months ago the African race in this City were literally hunted

down like wild beasts. They were shot down in cold blood, or stoned to

death, or hung to the trees or to the lamp posts. . . . How

astonishingly has all this been changed! The same men who could not have

shown themselves in the most obscure street in the City without peril of

instant death, even though in the most suppliant attitude, now march in

solid platoons, with shouldered muskets, slung knapsacks, and buckled

cartridge boxes down through the gayest avenues and busiest

thoroughfares to the pealing strains of martial music, and everywhere

are saluted with waving handkerchiefs, with descending flowers, and with

the acclamations and plaudits of countless beholders.

|