|

CONTRIBUTIONS TO UNION VICTORY

Charleston, the hotbed of secession, fell into Union hands in early

1865. Fittingly, the 21st U.S. Colored Infantry were the first Federals

to enter the city, followed closely by two companies from the 54th

Massachusetts. Richmond, the Confederate capital, held out until April.

Again, the honor of being the first Union troops to occupy the city went

to black soldiers.

At first, they were an unexploited resource, but once the Lincoln

administration lifted the ban, African Americans pulled on the uniform

and contributed mightily to the ultimate victory. Almost 179,000 black

men served in the Union army. They fought in 41 major battles and 449

minor engagements. Sixteen received Medals of Honor for valor on the

battlefield; many more deserved them but their conduct went

unrecognized. By the war's end, almost 37,000 black soldiers gave their

lives to the restoration of the union and the destruction of

slavery.

|

THE 55TH MASSACHUSETTS COLORED REGIMENT MARCHES INTO CHARLESTON.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

Shortly after the Confederate surrender, Major Martin Delany, one of

the highest-ranking black officers in the war, announced to a black

audience, "Do you know that if it was not for the black men this war

never would have been brought to a close with success to the Union, and

the liberty of your race if it had not been for the Negro?"

These words sound bold, perhaps even overblown. But his statement

differed little from Abraham Lincoln's own assessment. As early as

mid-1863, Lincoln foresaw emancipation and black enlistment as the

policy that would eventually win the war. "I believe it is a resource

which if vigorously applied right now, will soon close out the contest,"

he predicted to Grant. One year later, Lincoln argued that any true

supporter of the Union war effort must also endorse black military

service. "And now let any Union man who complains of the measure," he

challenged, "test himself by writing down in one line that he is for

subduing the rebellion by force of arms; and in the next, that he is for

taking these hundred and thirty thousand men from the Union side, and

placing them where they would be but for the measure he condemns. If he

cannot face his case so stated, it is only because he cannot face the

truth."

|

A SKETCH OF BLACK SOLDIERS MUSTERING OUT OF SERVICE IN ARKANSAS. (LC)

|

The following month, in even blunter terms, Lincoln admitted that the

Union could not win without the aid of African Americans. "Any different

policy in regard to the colored men," he explained, "deprives us of his

help, and this is more than we can bear. We can not spare the hundred

and forty or fifty thousand now serving us as soldiers, seamen, and

laborers. This is not a question of sentiment or taste, but one of

physical force which may be measured and estimated as horsepower and

Steam-power are measured and estimated. Keep it and you can save the

Union. Throw it away, and the Union goes with it."

By the end of the war, black soldiers had won the grudging respect of

virtually all white Union troops. The bulk of white men in Union blue

knew that the USCT had contributed in real and significant ways to Union

victory. Most of them retained their prejudices, but few would dispute

the assertion that blacks made good soldiers. And while many were

reluctant to grant African Americans the right to vote at that time,

quite a number did believe that the government should single out black

soldiers and bestow on them the franchise as a reward for honorable

wartime service. In 1870, adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment to the

U.S. Constitution resolved the debate by granting black people the right

to vote.

|

MEMBERS OF THE UNITED STATES COLORED TROOPS BURIED AT STONES RIVER

NATIONAL CEMETERY. (PHOTO BY LOU SMITH)

|

Many of the black units remained on active service long after

Appomattox, performing occupation duty in the Southern states and

serving in the West. But by 1867, the government had mustered them all

out of service. The USCT was no more. Six black Regular Army regiments,

later cut to four—24th and 25th Infantry Regiments and 9th and 10th

Cavalry Regiments—when Congress reduced the size of the army, stood

as its legacy.

Once they reached home, black soldiers were local heroes for the

important part they played in winning freedom for their race. Many of

them assumed leadership roles in the black community. Numerous black

politicians served in the USCT, while other black veterans occupied

positions of central importance outside the political arena. Elijah

Marrs, for example, rose to become a prominent clergyman in the postwar

world.

Returning soldiers had other advantages as well. Perhaps a half or

more learned to read and write in military service, which placed them in

a better position to succeed in freedom. With the pay and enlistment

bounties, black veterans were able to buy land, invest in businesses, or

finance more schooling, some of them even earning college degrees.

|

AFTER SERVING BRAVELY IN THE CIVIL WAR, AFRICAN AMERICANS WON THEIR

FREEDOM BUT NOT EQUALITY IN THE EYES OF MANY. (FW)

|

While many black soldiers benefited from their time in the Union

army, others struggled in their postwar years. If they returned to the

secessionist states, local whites made them feel unwelcome. They and

their families endured harassment, physical abuse, and economic

discrimination.

Some men had marched off to war in prime condition and returned as

physical wrecks. Veterans suffered debilitating wounds or illnesses and

were incapable of performing manual labor. They eked out meager

existences for the remainder of their lives, often dependent on a small

army pension as the source of their subsistence.

Saddest of all, though, with the passing of each decade, the white

population forgot more and more about black military service in the war.

And by the time of the First World War, black Americans had to fight all

the same stereotypes that their Civil War ancestors had battled half a

century before.

|

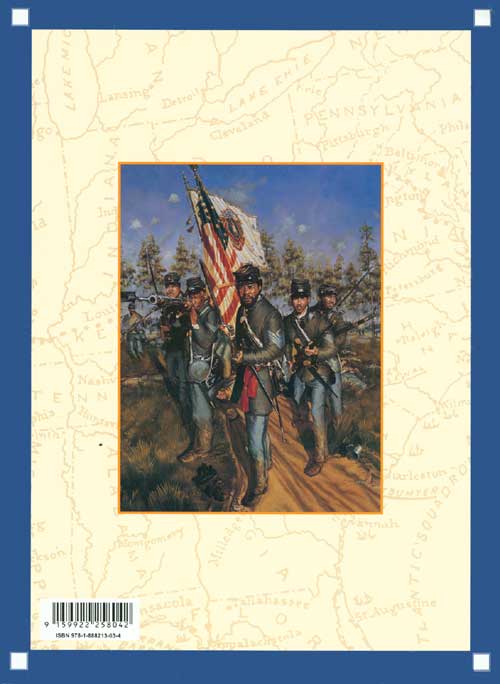

BACK COVER: 54TH MASSACHUSETTS VOLUNTEER INFRANTRY, BATTLE

OF OLUSTEE, FLORIDA, BY TODD HASKIN FREDERICKS, BURNSVILLE,

MN.

|

|

|