|

PREJUDICIAL TREATMENT

Black soldiers rapidly discovered that donning the Union uniform was

an uplifting experience, but the sensation was transitory. Black

soldiers needed proof positive that the Federal government would treat

them the same as white soldiers. They hoped that this crisis and the

overwhelming response to it would convince the government to treat all

soldiers alike, regardless of skin pigmentation. Yet men of African

descent had experienced the extraordinary power of prejudice. They

needed some demonstration of good faith on the part of their government.

Unfortunately, such equal treatment was slow in coming.

At the time of their enlistment, the very first black recruits

received assurance that they would earn the same pay as white soldiers.

That quickly proved false. The War Department, after consultation with

legal counsel, announced on June 4, 1863, that the Militia Act of July

17, 1862, which authorized the enlistment of black men into the army,

specified that pay was to be $10 per month regardless of rank, $3 of

which was for clothing, the same pay as black government laborers. This

decision touched off a firestorm of controversy.

|

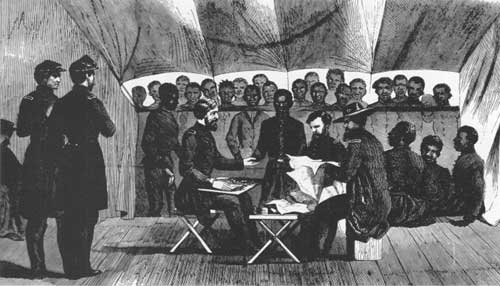

BLACK SOLDIERS RECEIVING THEIR PAY AT HILTON HEAD, SOUTH CAROLINA.

(FRANK LESLIE'S ILLUSTRATED NEWSPAPER)

|

Men in the 54th and 55th Massachusetts launched the protest by

refusing to accept inferior pay for equal work. Over the course of

eighteen months the government mustered the men for pay seven times. On

each occasion they declined it. When Governor Andrew of Massachusetts

proposed to provide the difference, they rejected the offer. It was not

the money, soldiers explained. It was the principle.

Black soldiers wrote to family, friends, newspapers, government

officials—anyone who would listen—complaining of this blatant

discrimination. In a letter to the editor of a prominent black

newspaper, an outraged soldier, fresh from the battlefield, demanded

equal pay for equal duty: "Do we not fill the same ranks? Do we not

cover the same space of ground? Do we not take up the same length of

ground in the grave-yard that others do? The ball does not miss the

black man and strike the white, nor the white and strike the black. But

sir, at that time there is no distinction made, they strike one as much

as another."

White officers in the USCT joined the chorus of protests. Powerful

Democrat and Major General Benjamin Butler could see no justification

for such discrimination: "The colored man fills an equal space in the

ranks while he lives and an equal grave when he falls." One lieutenant

even announced that if Congress did not address the pay inequality

question, he intended to resign: "I did not enter this service from any

mercenary motive but to assist in removing the unreasonable prejudice

against the colored race; and to contribute a share however small toward

making the negro an effective instrument in crushing out this unholy

rebellion."

When soldiers refused pay, their families suffered most. At least the

soldiers received meals and shelter. The family lost a primary wage

earner in the adult male. Frustration among black troops mounted

quickly, and grumbles progressed into mutinous words and occasionally

deeds. Officers tried their best to defuse the tense situation,

explaining the consequences of mutiny to their soldiers and urging them

to remain patient and work through the proper channels.

|

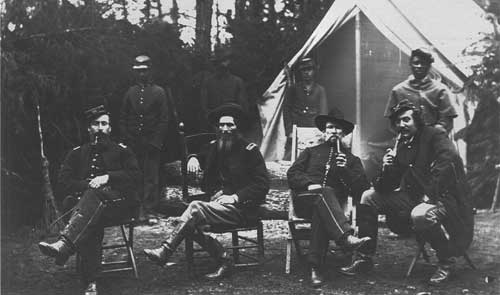

UNION OFFICERS WITH BLACK SOLDIERS IN THE BACKGROUND AT BRANDY STATION,

VIRGINIA. (LC)

|

Once supporters of equal pay mobilized their forces, they were able

to mount heavy pressure on national politicians. And in addition to

strong lobbying, important government officials began to side with the

black soldiers. The provost marshal general concluded that if the

government hired black men exclusively as laborers, then they could not

serve as substitutes for drafted white men. Attorney General Edward

Bates advised the president to pay black soldiers equal wages. Lincoln

had a constitutional obligation to apply all laws equally, Bates argued,

and in a court of law the government would most likely lose its case for

unequal pay.

In June 1864, Congress finally authorized equal pay for all soldiers

from January 1, 1864. But only African Americans free before the war

could receive equal pay before then. The furor resumed. It took another

nine months before Congress compensated all the victims of pay

discrimination. Even the euphoria over the passage of the Thirteenth

Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery, did not remove

all the sting from such blatant inequality.

|

|