|

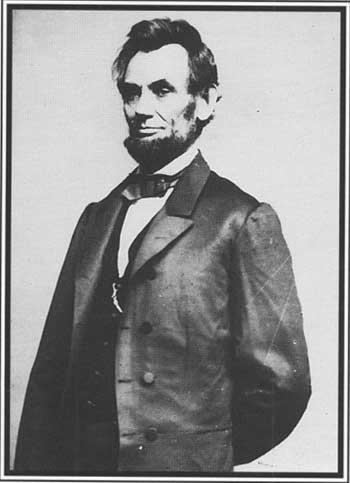

LINCOLN'S DECISION FOR EMANCIPATION

Initially, most Northerners regarded this as a white man's war and

saw no need to seek aid from the black population. In fact, many whites

feared the war would end before they had an opportunity to prove their

prowess in battle. But as months in military service dragged on into a

year and more, casualties and untold hardships compounded. By the early

summer of 1862, tens of thousands of Northern soldiers had taken their

final resting place, and untold more would live their remaining days

without limbs or in impaired health. Battlefield victories came

sporadically, if at all, and at great cost in human lives.

Discouragement and disillusionment slowed enlistment to a trickle and

spurred desertion and malingering. The war that Federals thought they

might miss had become a war that might never end. Union soldiers,

civilian advocates of reunion, and President Abraham Lincoln had reached

a critical juncture.

|

PRESIDENT ABRAHAM LINCOLN (NA)

|

Slowly yet steadily the cost of war forced them to re-examine their

commitment to restoring the Union. Some decided the price was too high

and withdrew their support or left military service. But most renewed

their faith in the Union cause. The purpose of the war was sound, they

reasoned. The problem was the way the Federal army fought it. Success

demanded a more vigorous prosecution of the war. "There is now no

possible hope of reconciliation with the rebels." Halleck told to Grant

in early 1863. "The Union party in the South is virtually destroyed.

There can be no peace but that which is forced by the sword. We must

conquer the rebels or be conquered by them." Pro-war northerners had to

view the Confederate nation, both soldiers and civilians, as their

enemy, and to consider anything that Confederates used to wage war as a

legitimate target of the Federal army. The Northern populace had to make

greater sacrifices and devote an enlarged share of their resources to

suppress the rebellion. They also had to increase the number of men in

uniform, to make the Confederate populace feel the hard hand of war.

|

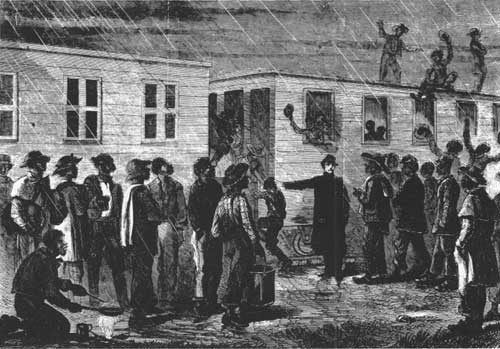

SLAVES WORKING AS COOKS IN A CONFEDERATE CAMP. (UC)

|

For some time, Abraham Lincoln had been expanding the scope of the

war. Early on, he had suspended habeas corpus and agreed to the

confiscation of Rebel property, including slaves who labored on

Confederate military projects, as a necessity of war making. Over the

first year of war, Lincoln and the Congress also had urged a dramatic

increase in the size of the armed forces and printed greenbacks to

finance the war. Before the year was out, they endorsed the first

conscription law and instituted an income tax to offset wartime

expenses.

|

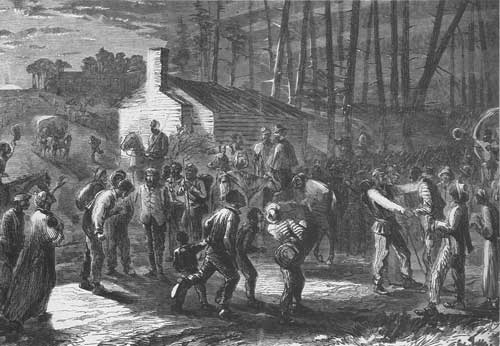

A WARTIME NEWSPAPER ILLUSTRATION OF BLACK RECRUITS BEING SENT OFF TO

BATTLE.

|

Within that atmosphere, Lincoln began to mull over the idea of

wartime emancipation and black enlistment. Personally, he disliked the

institution of slavery and had for decades. Yet the president was

hesitant to strike a major blow at the "peculiar institution." Many

Union loyalists, both North and South, owned slaves or supported the

concept of slavery, and others argued that they had no interest in

fighting a war over slavery. An astute politician, the president tried

to balance all interests, attempting to win the war, retain the loyalty

of slaveholding states, promote a Union party in the Confederacy, and

placate the demands of Northern radicals. Once he concluded that

Southern Unionists could not gain ascendancy over the secessionists, and

that the border states were secure he felt freer to implement more

extreme policies to aid the war effort. To newspaperman Horace Greeley,

Lincoln explained his position:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and

is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the

Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could

save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could

save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.

What I do about slavery and the colored race I do because I believe it

helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I for bear because I do

not believe it would help save the Union.

When the war had reached such magnitude that a true reunion of the

states without the destruction of slavery was impossible, the president

acted.

After wrestling with the issue for some months, Lincoln came to a

momentous conclusion. "Slavery is the root of the rebellion, or at least

its sine qua non [without which, there would be none]," he

explained to a White House delegation. "The ambition of the politicians

may have instigated them to act, but they would have been impotent

without slavery as their instrument." Emancipation would, as Lincoln had

said four years earlier, "place it where the public mind shall rest in

the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction."

In July 1862, Lincoln decided on emancipation and black enlistment in

the army. But at the suggestion of Secretary of State William Seward, he

delayed the announcement of emancipation until the Federals won a major

victory. Otherwise, the decree would look like a desperate gamble from a

losing nation. Unfortunately, the next major Union triumph on the

battlefield was in September, at Antietam, Five days later, he unveiled

to the world his plan for emancipation.

Lincoln refused to await a victory, however, to embark on black

military service. Enlistment had slowed, and the Union army needed

recruits as soon as possible. African Americans were the largest

untapped source of manpower. Thus he proceeded with his plan of black

military service cautiously, first endorsing Butler's federalization of

black militia units, then authorizing Higginson's formation of a black

regiment in South Carolina.

By scrawling his signature to the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln

was formalizing his position that slavery was at the heart of the

national crisis. Lincoln announced that the war had reached such scope

that a return to a union as it was in 1860 was no longer possible. If

the Northern states won, he was removing the single greatest cause of

sectional conflict, the institution of slavery, from the political

agenda.

Technically, the proclamation freed no one. It simply pledged that as

Federal troops conquered secessionist territory after January 1, 1863,

the slaves in that area became free. He justified the decision on the

basis of his constitutional powers in time of war. As commander in

chief, he could order the seizure of anything that aided the Rebel war

effort. Slaves most certainly did that. And to reinforce this decision,

both as a means of freeing slaves and embarking on a new and bold

approach to the war, Lincoln decided to put those freed men and any

other black males into the Union ranks.

For Lincoln it was a calculated risk. By taking slaves away from

secessionist supporters, he was depriving the Confederacy of valuable

laborers; and if these same slaves joined the Union ranks and performed

important service that helped win or shorten the war, then the policy's

success would silence its critics. As Lincoln explained to Grant, "It

works doubly—weakening the enemy and strengthening us." Lincoln

gambled that the military service of African Americans would vindicate

both his decisions.

To those who opposed emancipation and

black enlistment, Lincoln defended his action forcefully and cleverly.

The president simply argued that he was employing all means at his

disposal to restore the Union.

|

To those who opposed emancipation and black enlistment, Lincoln

defended his action forcefully and cleverly. The president simply argued

that he was employing all means at his disposal to restore the Union. "I

thought that in your struggle for the Union, to whatever extent the

negroes should cease helping the enemy, to that extent it weakened the

enemy in his resistance to you," he suggested. "Do you think

differently? I thought that whatever negroes can be got to do as

soldiers, leaves just so much less for white soldiers to do, in saving

the Union. Does it appear otherwise to you?" Whites, Lincoln shrewdly

contended, did not have to feel as if they were fighting for

emancipation. The ultimate objective of the war was still reunion.

"You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem

willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then, exclusively

to save the Union. I issued the proclamation on purpose to aid you in

saving the Union. Whenever you shall have conquered all resistance to

the Union, if I shall urge you to continue fighting, it will be apt

time, then, for you to declare you will not fight to free negroes."

|

BLACK SOLDIERS LIBERATE SLAVES IN NORTH CAROLINA. (LC)

|

|

|