|

ON THE BATTLEFIELD

After the valiant yet unsuccessful assault on Fort Wagner, the pace

of black recruitment accelerated. From a handful of regiments in the

summer of 1863, the ranks of the USCT swelled to massive proportions. By

late summer of 1864, some 100,000 blacks had donned the Union blue, and

before the war ended their numbers surpassed 123,000.

Black soldiers built fortifications, guarded critical bridges and

railheads, sustained the logistical pipeline, and performed sundry other

duties. But the reality of their situation was that black soldiers could

not gain the respect of Northern whites and attain the full and equal

civil rights they so desired unless they achieved success on the

battlefield. By the same token, failure in battle could cause

irreversible damage to their status in post-war America.

Time after time, black soldiers acted with unusual valor because they

so feared accusations of cowardice. They fought boldly, sometimes

recklessly, to demonstrate conclusively their character and commitment

to Union victory. "They had been to the armory of God," a black sergeant

explained, and had received weapons of the heart, that made them daring

and dangerous foes—men to be really reckoned with. For black

soldiers, the Civil War was their crusade.

|

TWO SOLDIERS AT DUTCH GAP, VIRGINIA. (OHIO HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

How well did they perform in combat? They fought as well and as badly

as white soldiers. When their officers trained and led them properly,

black units acted as gallantly in battle as any white regiment. When

their officers neglected or mistreated their troops, when they openly

expressed doubts about how well their men would act in combat, and when

they trained their men badly and led them poorly in battle, black

commands were as bad as white units with comparable leadership problems.

Perhaps Abraham Lincoln best assessed their combat effectiveness when he

wrote in 1864, "So far as tested, it is difficult to say they are not as

good soldiers as any."

Often high-ranking officers used them in assaults. Some felt this was

the optimal way to use their "innate savagery." Others justified their

employment in charges for a more conventional reason. They believed that

since excessive fatigue duty had cut so deeply into the drill time of

black units, they might have difficulties executing intricate tactical

maneuvers on the battlefield. Simple, direct assaults overcame that

problem. Only at Fort Wagner did a general officer recommend placing

black troops in the vanguard of the attack to rid himself of them. In

critical moments, when armies entered battle and officers scraped

together all available troops, generals were delighted to have black

soldiers.

|

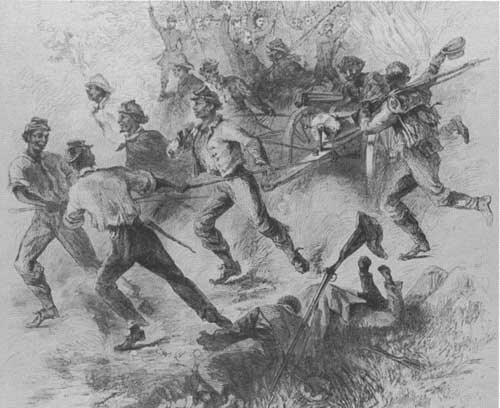

THREE BLACK REGIMENTS FOUGHT AT THE BATTLE OF OLUSTEE, FLORIDA, IN 1864.

(MH)

|

While black units fought during the fall and winter of 1863, it was

not until late spring or early summer of 1864 that the Federal armies

truly felt their impact. Union Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant

devised a strategy that placed as many soldiers in the field as

possible. With the huge increase in black enlistment during the previous

year, there were literally dozens of black regiments ready for

campaigning. In the siege of Petersburg thirty-three regiments, or

nearly one in every eight soldiers, was black. In the Military Division

of the Mississippi, Sherman preferred to keep his black soldiers more to

the rear, guarding railroads and pushing supplies forward. Nevertheless,

black troops under his overall command participated in numerous

engagements.

Probably the most famous battle involving black troops was the

Petersburg mine assault, more commonly known as "the Crater." Some

Pennsylvania troops, miners before the war, suggested a plan to tunnel

beneath the Confederate breast-works and detonate some explosives. With

the fortifications destroyed, Union troops could carry the position and

break the Confederate line. They worked strenuously to dig a long mine

and loaded it with gunpowder. On July 30, 1864, after an aborted try to

light the charge, the mine exploded. The blast created a huge crater on

the site of the Confederate line.

|

THE BATTLE OF THE CRATER. (LC)

|

The original plan called for a black division to lead the assault.

These troops had trained rigorously for the attack and looked forward to

the opportunity to carry the enemy works. But Major General George G.

Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, changed the plan. Fearing

political repercussions if the scheme failed and the black division

sustained heavy losses, he replaced the black troops with a white

division.

Union mismanagement, Confederate obstinacy, and the difficulty of

overcoming the huge pit that the explosion had created soon bogged down

the white troops. The Federals needed more men to exploit the break, and

the first reserve was the black division. The black troops drove rapidly

into the gap, but the Confederate army recovered quickly from the shock.

Rebel officers directed artillery fire to cover the front, and shot and

shell became so heavy that all the black troops could do was to hug the

ground. With infantry support, Confederates then sealed off the

breakthrough and fired on the attackers from the front and the

flank.

Disaster struck the Federals. Unable to advance and unable to

retreat, they were trapped in no-man's-land. Throughout much of the day

these Yankees hunkered down as best they could, exchanging fire

sporadically with their enemy. It was only a matter of time before the

Confederates gathered enough forces to launch a counterattack. When the

Rebels struck, they did so with intensity, and within a matter of

minutes they crushed Union resistance.

Rather than surrender, most Federals elected to risk their fate and

run the gauntlet back to Union lines. Many were mowed down in flight.

Others refused to give up. They fought with all their might until the

Confederate attackers simply overwhelmed them.

|

BLACK INFANTRYMEN HAUL IN CAPTURED GUNS AT PETERSBURG. (FW)

|

|

THE 1ST INFANTRY REGIMENT, USCT, FOUGHT AT PETERSBURG, CHAPIN'S FARM,

FAIR OAKS, AND OTHER SITES, (LC)

|

To prevent any more slaughter, a Federal general intervened and

ordered all troops in the crater to surrender. A pocket of Yankees did

not receive the word to cease fire, though, and they continued to shoot.

Some Confederates viewed the act as treachery and retaliated in kind by

bayoneting wounded black soldiers. When black soldiers saw their

comrades being massacred, they immediately grabbed their weapons and

launched yet another vigorous attack, this one with bullets, bayonets,

and rifle butts. Eventually, a Confederate officer restored order by

guaranteeing proper treatment for all prisoners. If these black soldiers

resisted, however, he promised every one of them would die. At the

urging of Federal officers, the last black soldiers dropped their

weapons and surrendered. The Battle of the Crater had ended.

As the black regiments rallied to tabulate their losses, the sight

was sickening. The 29th U.S. Colored Infantry entered the attack with

450 troops and exited with 128. Other regiments in the USCT sustained

casualties nearly that high. "I felt like sitting down & weeping on

account of our misfortune," an officer commiserated to a friend. In

total, the black regiments suffered over 40 percent of the fatalities

and 35 percent of the casualties, higher proportional losses than white

troops in the engagement.

At the battle of Chapin's Farm near Richmond, Virginia, in late

September 1864, Grant employed white and black troops in an attack on

the extreme left of Lee's line. The Union commanders called on black

units, on the far right of the attacking force, to charge over difficult

terrain against strong Confederate works. After working their way

through a maze of felled trees, black troops had to wade a swamp as they

approached the Confederate fortifications. Officers had instructed

troops to fix bayonets and not to fire. As their advance slowed to a

crawl in the swampy area, Confederates poured a withering fire on the

attackers. Black troops fell by the scores, and under such duress they

could not resist firing back. Men then stopped to reload, and

Confederates cut them down in huge numbers. Although his soldiers failed

to carry the Confederate defenses there, the commander of the Third

Brigade, Third Division, XVIII Corps, which consisted of the 4th and 6th

U.S. Colored Infantry, lauded the true valor of his men: "Ah! give me

the Thunder-heads & Black hearts after all. They fought splendidly

that morning, facing the red tempest of death with unflinching heroism."

One company lost over 87 percent of its men in the assault, and the 6th

U.S. Colored Infantry suffered 209 casualties out of 377 men who entered

the fight.

|

SERGEANT MAJOR CHRISTIAN FLEETWOOD OF THE 4TH USCT RECEIVED THE MEDAL OF

HONOR FOR HIS VALOR IN THE BATTLE OF CHAPIN'S FARM. (USAMHI)

|

The Second Brigade in that division, also consisting of black troops,

attacked near the Third Brigade. Like the men in the 4th and 6th U.S.

Colored Infantry, its soldiers had to traverse a swamp and had the same

problems with troops firing in the open. Nevertheless, the brigade

stormed the Confederates' defensive position along the New Market Road,

routed them, and held the line until reinforcements arrived. Their

losses that day were shocking. The Second Brigade entered the battle

with some 1,300 men and had 455 casualties.

Probably the worst Union disaster that day occurred when Brigadier

General William Birney directed black troops to charge Confederate Fort

Gilmer, an extremely well-defended position. Black soldiers plowed

through three ravines, filled with fallen timber, all the while under

heavy fire. Although many men were driven back, some managed to reach a

deep ditch outside the fort. Every time they shoved soldiers to the top,

Confederate blasts knocked them back. Rebel forces then began to lob

hand grenades and short-fuse shells down on them. The survivors had no

alternative but to surrender.

One month later, Grant used these black troops to divert Lee's

attention again, this time in an attack farther north. Like the assault

on September 29, this one failed, but the casualties were considerably

lower. At Chapin's Farm, although black units constituted a small

portion of the Federal force, they suffered 43 percent of the

casualties.

|

THE 1ST TENNESSEE COLORED BATTERY. (LC)

|

Far from the Petersburg trenches, inexperienced black regiment, the

5th U.S. Colored Cavalry, joined white troops in an attack on

Confederates at Saltville, Virginia, in early October 1864. Among the

Federals on the expedition were the 13th Kentucky Cavalry. Several

months earlier, these Kentuckians demonstrated such hatred of black

soldiers that they nearly murdered a recruiting officer in the USCT. As

they advanced toward Saltville, the Kentucky cavalrymen heckled the

black troops. But when they went into battle, the performance of the 5th

U.S. Colored Cavalry shocked their white comrades. These fledgling black

horsemen stormed Confederate works and drove back their adversaries. For

two hours they clung to their position. When no support arrived, their

officers withdrew them under the cover of dusk.

The sheer audacity of the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry in the face of

strong enemy resistance changed the opinions of the white troops in a

hurry. According to a captain in the 13th Kentucky Cavalry, he and his

men "never saw troops fight like they did. The rebels were firing on

them with grape and canister and were mowing them down by the Scores but

others kept straight on."

Despite their comparatively small numbers, men in the USCT played a

major role in the Battle of Nashville, where Major General George H.

Thomas's troops crushed the Confederate Army of Tennessee and ended

Lieutenant General John Bell Hood's Tennessee invasion. At Nashville,

the USCT sustained 630 casualties out of 3,500 men. As an officer in the

100th U.S. Colored Infantry walked over the battlefield, he gazed at the

terrible sight of hundreds of bodies, both black and white, all of them

clad in blue, who fell in combat. But strangely enough, the scene

uplifted him, too. "The blood of the white and black men," be noted.

"has flowed freely together for the great cause which is to give

freedom, unity, manhood and peace to all men, whatever birth or

complexion."

|

THE GUN CREW OF THE 2ND U.S. COLORED LIGHT ARTILLERY. (CHICAGO

HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

Probably the single greatest success of black troops was in the

Battle of Fort Blakely, Alabama, in April 1865. A division of black

troops held the extreme right of the Union position. Late in the

afternoon, its officers extended the skirmish line. Confederate troops

tried to resist the advance, but the Rebel pickets soon fell back

hastily to their main trenches. "As soon as our niggers caught sight of

the retreating figures of the rebs" explained an officer in the USCT,

"the very devil could not hold them their eyes glittered like serpents

and with yells & howls like hungry wolves they rushed for the rebel

works the movement was simultaneous regt. [regiment] after regt. and

line after line took up the cry and started until the whole field was

black with darkeys." The attack, unauthorized by the Union high command,

followed so closely on the heels of the Confederate skirmishers that the

defenders in the main fortifications could not fire on them without fear

of hitting their own men. As black soldiers poured into the works, the

Confederate line began to crumble. Moments later, an authorized Federal

assault all around the line completed the rout. Word of the scheduled

attack to the black division had miscarried, but they could not have

coordinated their charge any better.

|

BLACK MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENTS

In March of 1863 Congress established the Medal of Honor as the

United States's highest award for military valor. Eventually 23 black

servicemen—16 soldiers and 7 sailors—would receive the

prestigious decoration for gallantry in action during the Civil War, a

striking testament to the service and sacrifice of African American

volunteers in our nation's bloodiest conflict.

Perhaps the best-known of these deeds of valor occurred on July 18,

1863, during the desperate night assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina.

Twenty-three-year-old Sergeant William H. Carney of the 54th

Massachusetts raised the unit's fallen banner and carried the flag

across the moat of the fort and up the corpse-strewn ramparts. Though

bleeding from several wounds, Carney maintained his grip on the

bullet-riddled Stars and Stripes to the end of the fight and proudly

declaimed to his surviving comrades, "The old flag never touched the

ground." Though Carney did not receive his Medal until 1900, his was the

first battlefield exploit by an African American to earn the award.

|

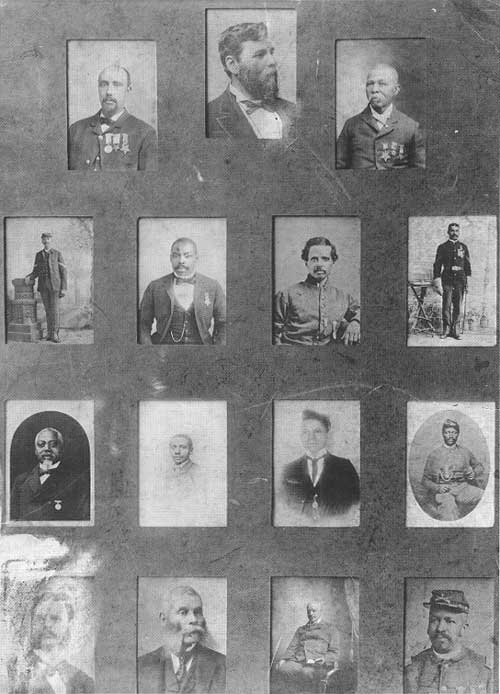

A COMPOSITE PHOTOGRAPH OF MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENTS. FROM TOP, LEFT TO

RIGHT: ROBERT A. PINN, MILTON N. HOLLAND. JOHN W. LAWSON; JOHN DENNY,

ISAIAH MAYS, FOWHATAN BEATY, BRENT WOODS; WILLIAM H. CARNEY, THOMAS R.

HAWKINS, DENNIS BELL, JAMES H. HARRIS; THOMAS SHAW, ALEXANDER KELLY,

JAMES GARDINER, CHRISTIAN A. FLEETWOOD (LC)

|

The greatest number of medals presented to black soldiers for a

single action came at the battle of New Market Heights, or Chapin's

Farm, one of numerous engagements during the nine-month-long siege of

the Southern strongholds of Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia. On

September 29, 1864, three brigades of United States Colored Troops

launched a determined attack against formidable Confederate defenses.

Their ranks thinned by a savage fire, the disciplined regiments pressed

on through a maze of obstructions—fallen trees and sharpened stakes

called abatis. When white officers fell dead or wounded, five

black sergeants took charge of their respective companies, and led the

onslaught toward the enemy position.

Sergeant Alfred B. Hilton was carrying the National Colors of the 4th

USCT, when the man bearing the regimental flag was felled beside him.

Hilton raised the fallen banner and pressed ahead with both flags until

a bullet in the right leg brought him down. When Hilton shouted, "Boys,

save the colors!" Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood and Private Charles

Veal leaped forward, picked up the flags, and pushed on to the

earthworks. "I have never been able to understand how Veal and I lived

under such a hail of bullets," Fleetwood recalled, "unless it was

because we were both so little fellows." Veal was the only member of the

Colored Guard to emerge from the fight unscathed, though his flagstaff

was severed and the silk pierced with twenty-two bullets. The gallant

standard-bearers were among fourteen African American soldiers awarded

the Medal of Honor for heroic conduct at New Market Heights.

Despite prejudice, unequal pay, and innumerable hardships, these

brave black soldiers exemplified the idealism and sacrifice of men with

a cause. As Medal of Honor winner William Carney put it, "We continued

to fight for the freedom of the enslaved and for the restoration of our

country."

—Brian Pohanka

|

As they had done with the white men in the 13th Kentucky Cavalry,

black units fought their way to respectability in the Union army. At

Decatur, Alabama, the 14th U.S. Colored Infantry received three hearty

cheers from some white troops for their excellent performance. On a

Union retreat in Arkansas, a Confederate force attacked some Federals at

Jenkins' Ferry. A white Yankee could not believe how well a black

regiment fought. "I am entirely whiped by the nigers," he confessed to

his sister. "They are as good if not the best soldiers we have. I

never would have beleaved it, but I have seen it with my own eyes and

there is no longer any doubt." In three tough fights on that campaign,

the black troops had fought well every time. Outside Petersburg in June

1864, three black regiments received an enthusiastic reception from

white cavalrymen and later soldiers in Winfield Scott Hancock's II Corps

of the Army of the Potomac. The white veterans treated the black

soldiers with newfound respect. "A few more fights like that," predicted

an officer in the USCT, "and our Col'd boys will have established their

manhood if not their Brotherhood to the satisfaction of even the most

prejudiced."

|

BLACK SOLDIERS AT CAMP. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

|

|