|

AND THE WAR CAME

The status of African Americans in America rested at the very core of

the Civil War. Most Southerners seceded and entered military service to

preserve their "rights" and to protect their homes, but the issue of

slavery was always central. Secessionists were attempting to safeguard

individual and states' rights from federal and Northern interference,

specifically the right to own property such as slaves and to take that

property anywhere without fear of loss or seizure; the right to retrieve

runaway property anywhere; and the right to live in peace, without

attempts by outsiders to subvert the existing order. Slavery was at the

heart of that order. As Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens

argued in 1861, the "corner-stone [of the new Confederate government and

nation] rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the

white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is

his natural and normal condition."

|

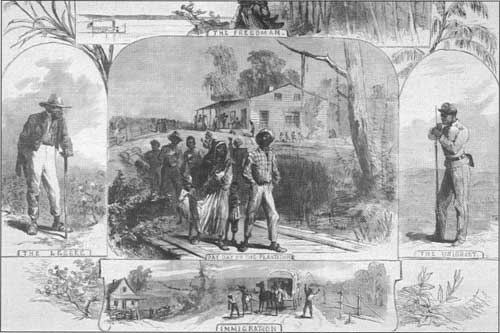

A PERIOD ILLUSTRATION OF "NEW PRAISE'S OF SOUTHERN LIFE." (FW)

|

More than anyone else, Confederate soldiers blamed the war on "Black"

Republicans and abolitionists. In the minds of most Confederate

soldiers, these Northerners were the arch-villains, the group that

provoked this wholly unnecessary crisis and shattered the greatest

government in the world through its antislavery activities. That deep

and abiding hatred toward abolitionists demonstrated the central role of

slavery.

Even more obscure but no less essential among Northerners was the

role of slavery. While many Yankees disapproved of the institution,

racial prejudice had penetrated deeply into Northern society. Few of the

early enlistees sought the destruction of the slave system as an

objective in war. Instead, Federals marched off under arms to restore

the Union. It took the keen mind of Abraham Lincoln to recognize that

the status of black people was the core issue of the war, something few

outside the black race grasped. Had northerners not found slavery

morally repugnant and the institution incompatible with the new

economic, political, and social directions of the country, Lincoln

reasoned, there would have been no war.

Nevertheless, whites on both sides wanted to keep blacks on the

periphery. In the Confederacy, several states allowed free blacks to

join the militia, and a small number offered their services. At the

time, few Southern blacks imagined that this would be a war against

slavery; rather, blacks and whites alike viewed the conflict as one over

the Union. Some free blacks in the South felt they could best

demonstrate their loyalty and enhance their position in society through

military service in this moment of crisis. "No matter where I fight,"

announced a black man who had volunteered to fight for the Confederacy

and a year later extended his services to the Federals, "I only wish to

spend what I have, and fight as long as I can, if only my boy may stand

in the street equal to a white boy when the war is over."

Yet President Jefferson Davis had no intention of opening the

Confederate ranks to black men, either free or slave. The entire premise

of black military service was incongruous with the fundamental concept

of slavery and would threaten the foundation of Southern society.

Georgia Governor Joseph F. Brown articulated this viewpoint most

concisely, arguing, "Whenever we establish the fact that they are a

military race, we destroy our whole theory that they are unfit to be

free."

With two hundred years of experience and tradition employing slave

labor, Confederates knew exactly how to use them: as laborers.

Throughout the war bondsmen performed a wide range of military and

nonmilitary duties. For the armed forces, they dug trenches, constructed

fortifications, maintained railroads, mined minerals, and manufactured

war equipment and material, all of which benefited Confederate troops.

In addition, slaves continued to plow the soil, hoe the fields, harvest

the crops, and tend to the livestock, producing vast quantities of

foodstuffs to feed the huge Confederate armies and the civilian

population. They grew cotton, which the Confederate government used to

purchase the tools of war abroad. Whites even let slaves cook meals,

drive wagons, and care for the personal property of soldiers. But in the

eyes of Southern whites, the distinction between service for the

military and military service was clear. The best way that slaves could

contribute to the Confederate cause was through their labor.

|

WHEN THE WAR BEGAN, THE CONFEDERATES USED SLAVES TO PERFORM HARD LABOR.

(FW)

|

In the Union, African Americans bombarded the government with

requests to serve in the military. Like some free blacks in the South.

most Northern men and women of African descent realized that the war

offered a rare opportunity for them. They could dispel race prejudice

and prove to all that they could contribute significantly to the nation

in times of crisis, all through military service. A black physician from

Michigan offered to raise five to ten thousand men in sixty days. Others

were not so ambitious and pledged to organize individual companies and

regiments for Federal service. Two prospective volunteers offered a

clever argument for military service, demanding that the Lincoln

administration "allow us the poor priverlige of fighting and (if need be

dieing) to support those in office who are our own choise."

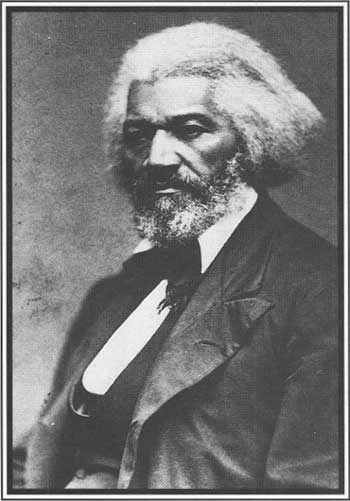

Frederick Douglass, a leading black abolitionist who had known the

hardships and indignities of slavery firsthand, grasped the essence of

the war just days after Confederates fired the opening salvo on Fort

Sumter. "The American people and the Government at Washington may refuse

to recognize it for a time," Douglass thundered, "but the 'inexorable

logic of events' will force it upon them in the end; that the war now

being waged in this land is a war for and against slavery; and that it

can never be effectually put down till one or the other of these vital

forces is completely destroyed." Four months later, Douglass led the

charge for black military service to help crush the rebellion. "This is

no time to fight only with your white hand, and allow your black hand to

remain tied," he counseled the Lincoln administration. "Men in earnest

didn't fight with one hand, when they might fight with two, and a man

drowning would not refuse to be saved even by a colored man."

|

A PHOTOGRAPH OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS TAKEN YEARS AFTER THE WAR. (NA)

|

Despite such evident logic, the government of Abraham Lincoln and the

Northern white populace were not convinced. Many believed this was a

white man's war and black men, because of their "innate" inferiority,

could contribute little toward subduing the Rebels. Others anticipated

the value of black soldiers but hesitated to advance the idea. Black

military service was a highly controversial notion, and the loss of

white support in the prosecution of the war might override all

advantages from increased manpower.

At the time, the concept of black enlistment offered little benefit

to the Lincoln administration. The president was walking a tightrope,

trying to retain the loyalty of the border states and foster Unionist

sentiment in the seceding states. A bold policy of black enlistment

would have driven many people in those states into the Confederate camp.

Anyway, Lincoln had more white volunteers than he could accept into

military service. Tens of thousands of whites were turned away, and

governors begged the president to raise state quotas for enlistment to

pacify their zealous constituents.

In one bold swoop, Butler had not only hired bondsmen to work for

the Union army, he had also established a policy that, in effect, freed

slaves.

|

MAJOR GENERAL BENJAMIN BUTLER (USAMHI)

|

|

|