|

PORT HUDSON

Black soldiers received the first large-scale opportunity to dispel

any doubts in May 1863 at Port Hudson, Louisiana. That spring, Port

Hudson and Vicksburg were the two remaining bastions along the

Mississippi River in Confederate hands. The War Department ordered Major

General Ulysses. S. Grant to capture Vicksburg. Responsibility for the

fall of Port Hudson fell to Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, head of

the Department of the Gulf.

For months the Confederates had been fortifying Port Hudson,

particularly to the south and west, taking full advantage of the choppy

terrain to erect an ominous defensive position. The occupation force

consisted of some six thousand Confederates under the command of Major

General Franklin Gardner.

|

THE FIRST LOUISIANA NATIVE GUARDS

SAW ACTION AT TEH FIGHT FOR PORT HUDSON. (FW)

|

In late May, portions of Banks's Nineteenth Corps fought their way

into a horseshoe-shaped position around the Port Hudson garrison, with

flanks nestled near the Mississippi River, The 1st and 3rd Louisiana

Native Guards, slightly more than one thousand black soldiers, occupied

a position on the north side, closest to the river, The 3rd Louisiana

Native Guards consisted of former slaves who had white officers,

Originally, the regiment had black line officers, but Banks purged the

unit of all black officers, regardless of qualifications or competence.

The 1st Louisiana Native Guards, though, were free blacks, with black

captains and lieutenants who for the time being were unwilling to buckle

under Banks's pressure.

|

A PHOTOGRAPH OF COMPANY C, 76TH U.S. COLORED INFANTRY AT ARTILLERY

PRACTICE AT PORT HUDSON (MH)

|

Among the officers of the 1st Louisiana Native Guards were Captain

André Cailloux and Lieutenant John Crowder. Educated in Paris and

fluent in both English and French, Cailloux was a man of great intellect

and property, a pillar in the free black community of New Orleans. Not

nearly as well known was Crowder, the young second lieutenant, Crowder

came from a poor but free black family and learned to read and write

through the efforts of his mother and a prominent black clergyman named

John Mifflin Brown. Crowder fibbed about his age, and at sixteen he may

have been the youngest officer in the Union army. "If Abraham

Lincoln knew that a colored Lad of my age could command a company,"

he once wondered, "what would he say[?]"

On the evening of May 26, 1863, Cailloux Crowder, and other men in

the two black regiments occupied their position for the attack the

following morning. The Federals were to pressure the defenders

everywhere and, Banks hoped, break through at various locations where

the Confederates were weakest, Yet for Cailloux Crowder, and their

comrades in the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards, the attack had a

special significance. The assault on Port Hudson offered them the first

opportunity to demonstrate to all witnesses that the black race could

match any white troops in prowess on the battlefield.

|

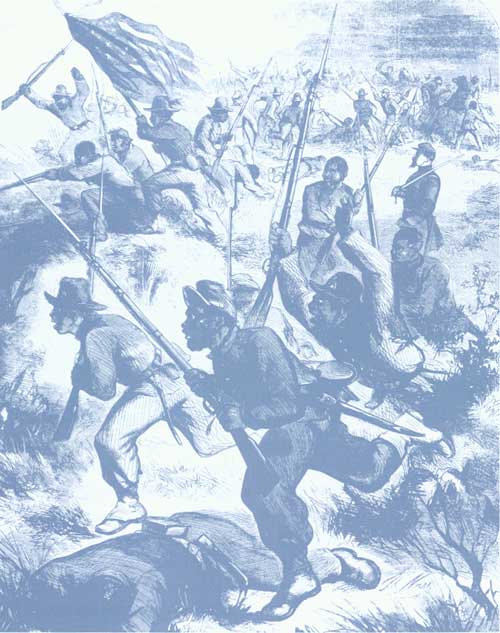

THE 2ND LOUISIANA COLORED REGIMENT ATTACKS THE CONFEDERATE WORKS AT PORT

HUDSON. (FW)

|

The next morning, when they assembled in position to begin their

advance, no one in the Federal army had explored the ground. Both

terrain and earthworks suited the defense superbly. The black regiments

were north of Foster's Creek and had to march over a pontoon bridge to

get at the Confederates. From there, the Telegraph Road led to Port

Hudson, A bluff ran parallel to the road on the Federals' left, and the

Confederate riflemen occupied choice positions there. It was virtually

impossible to dislodge these Confederates because the area between the

road and the bluff was choppy and filled with underbrush and fallen

trees. Even worse for the attackers, a Confederate engineer had tapped

into the Mississippi River and drew backwater directly through that

strip between the road and the bluff. Just west of the road was a huge

backwater swamp of willow, cottonwood, and cypress trees. To the front

of the advancing troops was a bluff, well protected by Confederate

infantrymen and supported by artillery.

The first assault came from troops to the east of the two black

regiments. When those blue columns failed to shatter the defense, the

burden shifted to the Native Guards. Around 10 A.M. they began crossing

the pontoon bridge over Foster's Creek. Within seconds they came under

Confederate sharpshooters' fire. Comrades fell to the ground lifeless.

The uninjured quickly pushed over the span and deployed as skirmishers,

working their way along the right side of the road. While the willow

trees provided some cover, the backwater and felled timber slowed their

advance. Then Confederate artillery began dropping shells among them,

further depleting their ranks.

|

THE FUNERAL OF CAPTAIN CAILLOUX AS SKETCHED BY A MEMBER OF THE NATIVE

GUARD. (FW)

|

Among the timber, six hundred yards from the main Confederate works,

the black regiments halted, regrouped, and shifted to their left. They

formed two battle lines consisting of two rows each, with the 1st

Louisiana Native Guards in the advance. From the woods they emerged,

advancing rapidly. As they cleared the timber, the Confederate riflemen

on the bluff alongside the road peppered them in the flank, ripping gaps

in the ranks. The black troops pressed onward. At two hundred yards from

the main works, the Confederates let loose a shower of canister, shells,

and rifle fire that tore through their lines. Raw courage alone

sustained the survivors, who charged on toward their slaughter. When the

sheets of Confederate lead staggered the first regiment, the 3rd

Louisiana Native Guards forced their way to the front.

Both the Union and Confederate commanders on the scene counted three

charges. Not once did black soldiers break the Confederate line.

Nevertheless, the black troops demonstrated dash and courage in the face

of overwhelming odds. Some soldiers attempted to wade through the

backwater to get at the Confederates, and a handful of others tried to

scale the bluff where the riflemen had posted themselves. Everything

failed. The Confederate defensive position was too strong.

|

AFTER PORT HUDSON MANY NORTHERNERS BELIEVED THAT BLACK TROOPS WOULD HELP

THE UNION WIN ON THE BATTLEFIELD. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

In defeat, these Louisiana Native Guards exhibited unusual grit. At

the height of the battle, a captain observed a black soldier limping

away from the hospital and toward the front. When he asked the soldier

where he was going, the fellow replied, "I been shot bad in de leg,

Captain, and dey want me to go to de hospital, but I guess I can gib 'em

some more yet." Another soldier had a shell take off his leg below the

knee. His captain, standing nearby, rushed over to comfort the soldier

and promised they would return to care for him, "Never mind me take cair

of yourself," the infantryman advised his captain. He then pulled

himself on a log and "Sat With his leg a swing and bleeding and fierd

thirty rounds of Amunition." The soldier died a few days later.

Nearly two hundred black troops were casualties, some 20 percent of

the two regiments. To highlight the utter futility of the assault, they

had inflicted no casualties upon the Confederates. Among those who never

returned was Lieutenant John H. Crowder. He suffered a critical wound,

was borne to the rear, and died that day. His grieving mother gave him a

pauper's funeral, all she could afford.

Captain André Cailloux also fell. He had survived much of the

battle, despite a rifle ball that shattered his arm below the elbow.

Throughout the rest of the fight, it hung lifelessly at his side. Around

1 P.M., just before the final retreat, Cailloux was still at the head of

his company. His voice hoarse from shouting over the gunfire and his

body weak from blood loss, he led his men onward one last time. A shell

struck him down permanently. After the battle, Union and Confederate

troops declared a truce to retrieve the wounded and bury the dead. The

pact did not apply to the sector where the black troops had fought. For

six more weeks, until the Confederate garrison capitulated, Cailloux's

body decomposed on the field. Not until late July did Cailloux finally

receive a proper burial. Thousands of New Orleans black mourners,

patriots all, turned out for his funeral. "The cause of the Union and

freedom," declared a New Orleans newspaperman, "has lost a valuable

friend."

The Battle of Port Hudson marked a turning point in attitudes toward

the use of black soldiers. A lieutenant in the 3rd Louisiana Native

Guards "entertained some fears as to their pluck. But I have now none."

Their dash convinced another officer: "They have shown that they can and

will fight well." Banks, who wanted nothing to do with black officers,

endorsed the concept of black enlisted men in his report to Commanding

General Henry W. Halleck. "The severe test to which they were

subjected," Banks wrote, "and the determined manner in which they

encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate

success." The New York Times, which had cautiously endorsed the

limited use of black troops on a trial basis just four months earlier,

now declared the experiment a success: It was no longer possible to

doubt the bravery and steadiness of the colored race, when rightly

led.

|

|