|

ENLISTMENT

As Union armies penetrated deeper into the South, liberating more and

more blacks from the yoke of slavery, authorities began to employ these

laborers for Federal benefit. For more than two centuries they had

produced bountiful crops and goods for slaveholders; surely these freed

man and women could direct their efforts on behalf of the Union war

effort. Government officials placed woman, children, and elderly and

unfit men to work on abandoned plantations to raise cotton and

foodstuffs. Able-bodied males labored for the army, performing a variety

of support duties which freed more soldiers for combat. The demands of

large-scale war were pushing the Lincoln administration steadily toward

black military service.

Precedent supported their admission into the armed forces. In the

American Revolution, black soldiers had fought valiantly in the

Continental army. George Washington reluctantly accepted them into his

army only with the proviso that all who entered military service

received their freedom. During the War of 1812, men of African descent

fought most conspicuously alongside Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New

Orleans. Only in the war with Mexico, which demanded limited numbers of

troops, did the government officially bar black Americans from the

ranks.

More important, black men had already secured entry into the United

States Navy. Although official figures are difficult to ascertain,

perhaps 20,000 to 30,000 African Americans actually joined the navy.

During the war black sailors manned ships in the blockade and fought on

numerous occasions in river operations. None appear to have received

commissions as officers. Still, they served in every capacity on the

enlisted level with distinction. Four black sailors received Medals of

Honor, and Robert Smalls, who seized control of a vessel and piloted it

out of Charleston Harbor, became a national hero for his exploits.

Yet this was predominantly a ground war, and it was in the army that

black men had to make their mark. No one was more aware of that fact

than Frederick Douglass. His editorials harangued the Lincoln

administration for its unwillingness to admit African Americans into the

Federal army. "Colored men were good enough to fight under Washington,"

Douglass scolded the president. "They are not good enough to fight under

McClellan. They were good enough to fight under Andrew Jackson. They are

not good enough to fight under Gen. Halleck. They were good enough to

help win American independence, but they are not good enough to help

preserve that independence against treason and rebellion." On the

battlefield alone, Douglass acknowledged, could black people secure the

full and equal rights they sought. "Once let the black man get upon his

person the brass letters, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and

a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket," he predicted, "and

there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right

of citizenship in the United States."

|

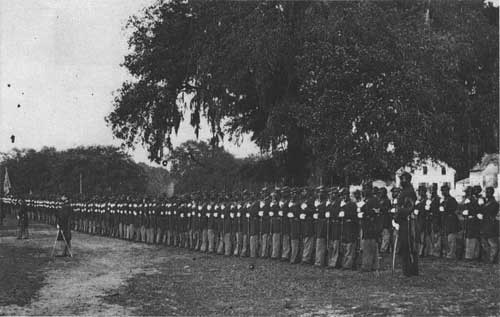

THE 1ST SOUTH CAROLINA VOLUNTEER'S INCLUDED THE FIRST UNIT OF FORMER

SLAVES TO BE MUSTERED INTO THE U.S. ARMY. (LC)

|

During the first fifteen months of the war, Lincoln certainly had

opportunities to permit black men to serve in the army. Manpower

shortages and abolitionist sympathies convinced several general officers

to advocate black enlistment, and a few of them actually overstepped

their authority and organized military units composed of African

Americans. Each time, the Lincoln administration rebuffed these

efforts.

The first scheme to arm black men occurred along the coastal islands

of South Carolina. When Acting Secretary of War Thomas A. Scott ordered

Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman to head an expedition to seize the

area, he authorized Sherman to use the services of anyone, "fugitives

from labor or not, who offered it." He could employ them any way he saw

fit, as long as this was not "a general arming" for military service.

Sherman adhered strictly to the guidelines and did not use them for

military purposes. His successor, however, did not hesitate to place an

expansive spin on those instructions.

In late March 1862, Major General David Hunter, a West Point graduate

with antislavery leanings, succeeded Sherman to the command in South

Carolina. Deriving his authority from the orders given to his

predecessor, Hunter declared martial law and promptly emancipated all

slaves in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Hunter brought in

escaped male slaves under gunpoint for a meeting. There he announced

plans to organize military units with fugitive blacks and made clear

that they were all volunteers. Such a harsh method of recruitment

alienated the local black population. Hunter than worsened the situation

by neglecting to inform the War Department of what he had done. The

Lincoln administration learned of Hunter's activities through newspaper

reports and Treasury Department correspondence.

Eventually, Lincoln could have sustained Hunter. In the Militia Act

of July 17, 1862, Congress empowered the president to organize African

Americans and use them "for any military or naval service for which they

may be found competent." Nevertheless, Lincoln elected not to endorse

Hunter's decisions. He believed that black enlistment was a delicate

issue, one that required careful planning and cautious execution.

Hunter's unauthorized foray into policy-making smacked of poor timing

and mismanagement.

|

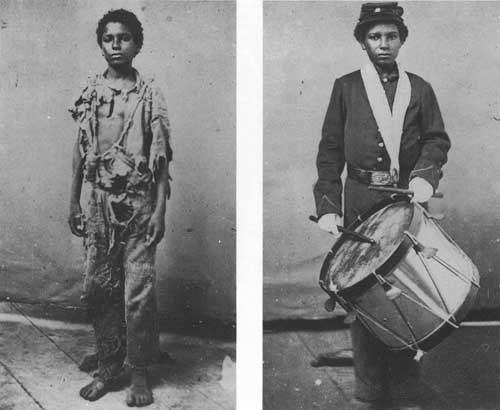

ON THE LEFT IS A PHOTOGRAPH OF A SLAVE NAMED JACKSON. ON THE RIGHT IS

JACKSON AS A DRUMMER IN THE UNITED STATES COLORED TROOP'S. (USAMHI)

|

At the heart of the second scheme to create a black regiment was U.S.

Senator Jim Lane, a diminutive yet tough-minded politician who concerned

himself more with results than rules. In 1862, Lane resigned his seat to

accept a commission as brigadier general, with the duty of recruiting

military units back home in Kansas. Among Lane's newly formed commands

was a regiment of black soldiers. Although Lane lacked specific

permission from the War Department to raise black units, he apparently

hoped that his political influence and the actual existence of such a

regiment would win governmental approval. He was wrong. Twice the War

Department notified him that he had no authorization to raise a black

regiment and must disband it immediately, and twice Lane simply ignored

the order. In January 1863, the Federal government finally accepted the

services of his black regiment, the 1st Kansas Volunteer Infantry

(Colored). By then, though, many of its troops had already seen

combat.

Louisiana, too, was scene of a bizarre episode of black recruitment.

After a joint army-navy expedition captured New Orleans in April 1862,

Benjamin Butler assumed command of the occupation forces. In Virginia,

Butler had acted boldly in the formation of his contraband policy. This

time, when a subordinate demanded that he organize black men into

regiments, Butler hesitated, and to the War Department he even voiced

doubts about the utility of black soldiers.

Brigadier General John W. Phelps, like Hunter a West Pointer and an

abolitionist, regarded black enlistment as a military and social

necessity. Blacks, Phelps argued, could offset the Federal manpower

shortage in Louisiana, and the structure and discipline of military

service would help to ease the transition from slavery to freedom once

Southern society collapsed. Ha welcomed and aided fugitive slaves in

their attempts to reach Union lines. Then, without authorization, he

organized the freedmen into five companies and requested arms and

accouterments for them.

|

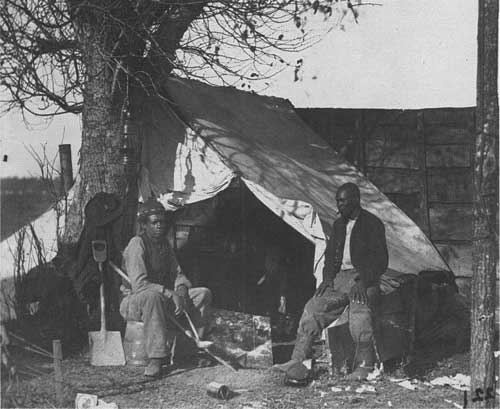

CONTRABANDS AT REST IN A UNION CAMP. (LC)

|

Butler, who had not yet learned of Phelps's activities, directed him

to employ the fugitives to assist in the preparation of defensive works

by cutting down trees and building fortifications. Phelps exploded in

fury. He would order black soldiers to perform such labors, but he would

not act as a "slave driver." Phelps then tendered his resignation and

requested an immediate leave of absence.

Only the president had the right to raise black military units,

Butler explained, and at present Lincoln declined to exercise that

authority. The fortifications were absolutely essential for their

defense, and the use of fugitive slaves for their construction was

standard practice. The government had drawn on black labor in other

theaters, and the men would receive pay for their work. Butler then

urged Phelps to withdraw his resignation.

|

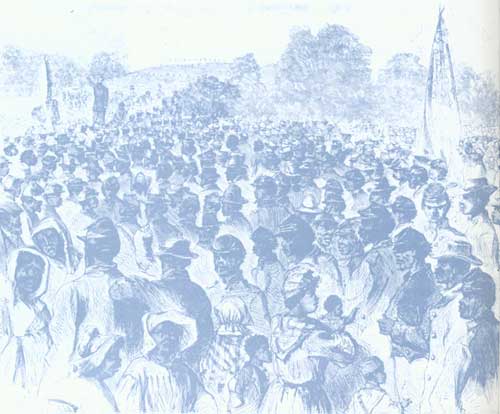

A SCENE IN LOUISIANA OF A UNION GENERAL ADDRESSING BLACKS ON THE DUTIES

OF FREEDOM. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

Butler's words failed to soothe his subordinate's ire. The government

accepted Phelps's resignation.

A bizarre twist concluded the Phelps controversy. Just a few weeks

after he sent Phelps's resignation to Washington, Butler changed his

mind on black soldiers. In the intervening time, he had received a

letter from Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. Conveying

sentiments that Lincoln had expressed in a cabinet meeting, Chase

suggested that the time was right for the formation of black regiments.

Since Butler desperately needed manpower and had initiated the

contraband policy, he was the logical person to enlist African Americans

in the army first.

Fortunately for Butler, he had the ideal recruits for the first black

regiments in some local militiamen. These were free blacks whose

ancestors had fought in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. They were men

of considerable means, either skilled workers, professionals, or

entrepreneurs. When hostilities broke out, they volunteered to serve for

the Confederate government. With Federal occupation of New Orleans. they

had immediately tendered their services to Butler. In May 1862, he

declined their offer; three months later, fortified by Chase's

recommendation, Butler accepted these free black militia men into the

Union army, and the War Department promptly endorsed it.

What made the decision to accept them into the army even more

eventful was that Butler brought these militia units into Federal

service with their black officers. At one time the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd

Louisiana Native Guards (later 73rd, 74th, and 75th U.S. Colored

Infantry) all had black captains and lieutenants and one regiment, the

2nd Louisiana Native Guards, had a black major, Francis Dumas.

Shortly afterward, prominent abolitionist and Massachusetts infantry

captain Thomas Wentworth Higginson received authorization to recruit the

first black regiment from scratch. Higginson returned to the South

Carolina coastal islands, where Hunter had alienated so many freedmen

with his overbearing enlistment" methods, Painstakingly, Higginson won

over the local black men and formed the 1st South Carolina (Union)

Infantry (later 33rd U.S. Colored Infantry). Unlike the Louisiana Native

Guards, whites constituted the officer corps in the 1st South

Carolina.

|

BLACK OFFICERS OF THE FIRST LOUISIANA NATIVE GUARDS. (FW)

|

Within the first six months of 1863, recruitment of numerous black

regiments was underway. The War Department finally accepted Lane's

regiment for official military service, and conscientious efforts to

form black units had progressed handsomely in Louisiana and Mississippi.

To the north, Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew successfully lobbied

the War Department for authorization to create a regiment composed of

free blacks. Again, all the officers were white.

|

|