|

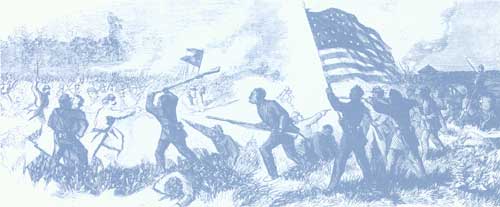

MILLIKEN'S BEND

Barely ten days after the fight at Port Hudson, black troops were

again thrust into battle. The fight took place along the Mississippi

River, this time at a place called Milliken's Bend. Five thousand troops

were sent to crush the new black regiments that were forming there and

disrupt Union efforts to capture Vicksburg and Port Hudson.

To counteract the Rebel advance, the commanding officer at Milliken's

Bend, Colonel Herman Lieb had a gun boat, four understrength black

regiments with only a few days of training and antiquated Belgian

muskets, and two understrength companies from the 23rd Iowa Infantry,

some thousand men in all. The gunboat provided the artillery

support.

|

BLACK TROOPS BATTLE WITH CONFEDERATES AT MILLIKEN'S BEND. (FW)

|

Fortunately for Lieb, the terrain provided some compensation for his

command's inadequate size and lack of experience. Because the water

level on the Mississippi River was low, the riverbank was serviceable as natural

earthworks for the Federals. A flat, open area, some 150 yards in length

and one-quarter of a mile in width, extended beyond that. Black

soldiers had established their camp there. At the western border of this

area was a six-foot-high levee. Because of his manpower shortage,

Lieb's left flank was open, but another cross levee and the hedges

channeled attackers into an open field where the defenders had a clear shot

at them.

On June 6, Lieb skirmished with some Confederates and fell back to

camp. Immediately, he doubled the pickets and placed some mounted

soldiers well outside the line for early warning. He directed the

remaining troops to take positions behind the levee. On the extreme left

was the 9th Louisiana Infantry (5th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery), and

next to it was the 1st Mississippi Infantry (51st U.S. Colored

Infantry). In the center Lieb placed the 13th Louisiana Infantry (63rd

U.S. Colored Infantry) and the 23rd Iowa, and on the far right he

positioned the 11th Louisiana Infantry (49th U.S. Colored Infantry).

A brigade of Confederates, 1,500 strong under Brigadier General Henry

F. McCulloch, pursued the retreating Federals vigorously and began

driving in the pickets before 4 A.M. McCulloch quickly deployed his

column some three-quarters of a mile from the Federal line and

struck with a vengeance. "No quarters for

white officers," shouted Rebel troops, "kill the damned

Abolitionists, but spare the niggers." During the course of the battle

they executed at least two white officers.

|

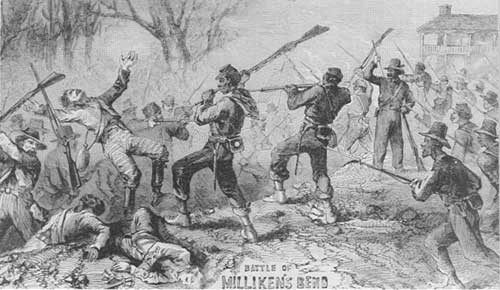

THIS WARTIME SKETCH SHOWS THE INTENSE HAND-TO-HAND COMBAT

AT MILLIKEN'S BEND. (FW)

|

Resisting the impulse to shoot too soon, the defenders held fire

until the Confederates were two hundred yards away. Despite their

inadequate training with firearms, rounds crashed through the Rebel

ranks. For a moment, the volley stunned the attackers, but the

Confederate troops regained their momentum. Onward they pressed.

For the next few minutes soldiers

battled hand-to-hand. Men clubbed, slugged, wrestled, and jabbed at

their enemy with muskets and bayonets.

|

Courage could not compensate for inexperience among the black

Federals. Under the enormous stress of the assault, untrained black

soldiers were unable to reload rapidly enough. Through gaps in the

hedges screaming Rebels poured, assailing the Union troops behind the

levee. Since most Confederates had not fired their weapons, they

discharged as they came over the top. For the next few minutes soldiers

battled hand-to-hand. Men clubbed, slugged, wrestled, and jabbed at

their enemy with muskets and bayonets. "It was a horrible fight,"

insisted a white captain of black soldiers, "the worst I was ever

engaged in, not even excepting Shiloh." He personally suffered two

bayonet wounds, and his men "met death coolly, bravely; not rashly did

they expose themselves, but all were steady and obedient to orders."

Lieb had withheld two understrength companies in reserve. Now they

joined the melee. Their commander knew that these were green troops, and

they would most likely shoot high in the excitement. He ordered his men

to fire only if the muzzle touched a Confederate. For these untrained

men, the bayonet would serve as their primary weapon. Once Lieb

unleashed them, they struck with a fury, reviving their embattled

comrades.

For a few moments it seemed that the Federals might hold. Then just

as suddenly the tide shifted when the

Confederates seized a position on the extreme left portion of the

levee and poured a murderous enfilading fire down the line. This

stampeded the two companies of Iowans from the field. As Confederate

General McCulloch described it, "the white or true Yankee portion ran

like whipped curs almost as soon as the charge was ordered," while the

black soldiers resisted with "considerable obstinacy." Nonetheless, the

black soldiers buckled under the weight of the Confederate onslaught.

Outflanked, nearly all the Federals abandoned the levee for the

riverbank. Only the men on the extreme right behind the old cross levee

and cotton bales managed to repel the assaults.

Several times the Confederate officers hurled their men forward,

hoping to drive the black troops into the river. But they never gained a

toehold on the river bank. After a long march, an early morning

advance, and several hours of vicious fighting, exhaustion set in. For

the remainder of the day, they were unable to mount an effective charge.

"Those negro bayonets," crowed a Union officer, "had got on to their

nerves."

When the attack lost its momentum, McCulloch requested

reinforcements to continue the fight, but they never arrived. Stung by

unanticipated Federal resistance, and unable to advance in force after

several hours of work, the Confederate commander decided to withdraw.

The Battle of Milliken's Bend, one of the most desperate in the entire war, had

ended.

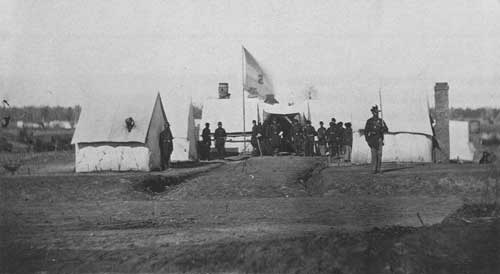

|

HEADQUARTERS OF THE SECOND BRIGADE, EIGHTH CORPS

D'AFRIQUE. THIS REGIMENT FOUGHT AT LAKE PROVIDENCE,

LOUISIANA. (MH)

|

Casualties in the fight were staggering. McCulloch's force suffered

44 killed and 131 wounded. For the Federals, losses were horrendous.

When Acting Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter arrived on the scene a few

hours after the battle had ended, he could not help noticing that "the

dead negroes lined the ditch inside of the parapet, or levee, and most

were shot on the top of the head." Among the black troops, 35 percent of

those in the fight were killed or wounded. Well over two hundred more

were missing, although Lieb believed that many of those troops wandered

off sometime after the battle and were not present at roll call. In the

9th Louisiana Infantry, nearly 45 per cent of its men were killed or

mortally wounded. That was the highest proportion of killed and mortally

wounded in a single battle throughout the entire war, nearly 17 percent

higher than that of the next nearest regiment, the 1st Minnesota

Infantry at Gettysburg.

Troops from only one black regiment acted badly, and that was

because their commander and several other officers removed themselves

from the view of their men. When the troops saw no officers, they felt

deserted and some abandoned their posts. Otherwise, these black troops

exhibited extraordinary valor, refusing to leave their comrades. "Many

of the severely wounded voluntarily returned to the ranks after washing

their wounds," noted the commander of the 1st Mississippi Infantry.

The performance of the black troops impressed

everyone who witnessed the battle or examined its

aftermath.

|

The performance of the black troops impressed everyone who witnessed

the battle or examined its aftermath. "I never more wish to hear the

expression, 'The niggers wont fight,'" insisted a captain in the

engagement. Another captain of white troops who observed the black

soldiers in action that day announced to Major General Ulysses S. Grant,

"The capacity of the negro to defend his liberty, and his susceptibility

to appreciate the power of motives in the place of the last, have been

put to the test under our observation as to be beyond further doubt."

And Charles A. Dana, a noted journalist and Secretary of War Edwin M.

Stanton's emissary and investigator, gleefully pronounced the

experiment of black soldiers a success. "The sentiment in regard to the

employment of negro troops has been revolutionized by the bravery of the

blacks in the recent battle of Milliken's Bend," Dana reported to

Stanton. "Prominent officers, who used in private to sneer at the idea,

are now heartily in favor of it."

|

|