|

THE BUREAU OF COLORED TROOPS

Despite the resistance of many whites, the recruitment of African

Americans into military service proceeded at an almost breathless pace,

which produced a new administrative weight that quickly overwhelmed the

Adjutant General's Office. Queries for information, requests for

appointments to recruit and serve in these new units, mountains of paperwork

for enlistees, and orders to organize and equip these commands began to

suffocate its personnel in an avalanche of documents. To compound these

problems, black regiments required special consideration. The Federal

government placed unusual demands on its officers and men and more

carefully supervised the recruitment process. In the North, state

governments had a hand in the creation of new regiments. Most of the

black units, however, would have ex-slaves as their enlistees, and

they would come predominantly from seceding states. The Federal

government would direct the recruitment of those black units.

By mid-1863, the administrative load became so burdensome that the

War Department decided to create a single entity under the umbrella of

the Adjutant General's Office, called the Bureau of Colored Troops, to manage its

affairs. Headed by Major Charles W. Foster, the bureau was to

systematize the process of raising black units and securing officers for

them. It also served as a clearinghouse of information on these

units.

|

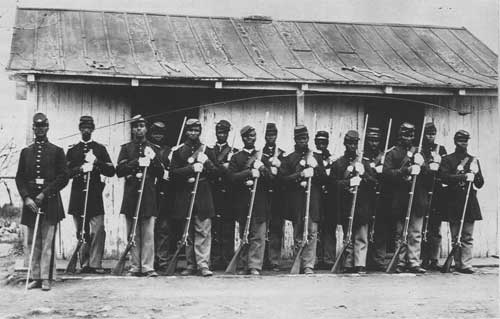

MEMBERS OF THE GUARD OF THE 107TH INFANTRY REGIMENT,

U.S. COLORED TROOPS, AT FORT CORCORAN, WASHINGTON, D.C. (LC)

|

Over the course of the next year, the War Department began to change

the names of black commands. Instead of state designations, they became

United States Colored Troops (USCT), and the various units became United

States Colored Infantry, Artillery, or Cavalry. Of all the black

regiments, only the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, 55th Massachusetts

Infantry, 5th Massachusetts Cavalry, and 29th Connecticut Infantry

retained their original state designations.

With Foster at the helm, the Bureau of Colored Troops administered

more than 186,000 black and white officers and men during the war. At

one time the Bureau of Colored Troops had over 123,000 soldiers in

uniform, a force larger than the field armies that either Lieutenant

General Ulysses S. Grant or Major General William T. Sherman directly

oversaw at the height of their campaigns in 1864 and 1865.

|

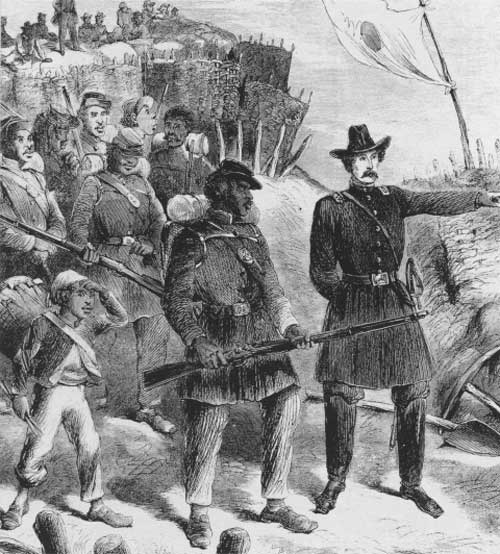

THIS ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY SHOWS A

UNION OFFICER TEACHING RECRUITS HOW TO USE THEIR RIFLES.

|

Because of the controversial nature of black military service, the

Lincoln administration determined that whites should officer the new

black regiments. Those black officers in the Native Guards could stay,

although Banks intentionally drove them all out of the army by early

1864. In selected cases, the War Department would permit them to serve

as chaplains and surgeons. Otherwise, African Americans

were barred from the officers' ranks.

By offering commissions to whites, the War Department hoped

to appease objectors in and out of the army. Those whites who

endorsed the concept of black military service and

assisted in its execution could gain commissions or

promotions to higher rank. Individuals who opposed the formation of black regiments received

reassurance that they would not hold commissioned rank over white

enlisted men. In short, whites would remain in charge.

Racial stereotypes, too, played an important role in the decision to

dole out commissions only to whites. Since most white Northerners

doubted that black men had the innate ability to fight well and believed

that their inferior character would prevent them from becoming good

soldiers, these new black regiments would require committed and talented

white officers to train and lead them.

The Federal government decided to screen prospective officers

carefully. Some were individuals whom prominent politicians knew to be

sympathetic toward black people, and they received direct

commissions. But the rapid expansion of black units in the latter

half of 1863 and throughout 1864 and the ensuing demand for white

officers compelled the government to devise more efficient ways of

selecting officers. The problem was that there was no sure-fire method

to determine an individual's capacity for leadership and his attitudes

toward African Americans. The best the government could do was to seek

out moral white men with military knowledge who also had a liberal arts

background, which reflected a more well-rounded individual. By mid-1863,

the Adjutant General's Office established boards to certify the

qualifications of prospective officers.

While many officers in the USCT were political appointees, a majority

passed an examination. This ensured a degree of selectivity and

competence among officers of black units that did not exist in white

regiments. Most officers of white troops obtained their commissions

through political contacts or election by their comrades. They learned

on the job. Nearly all officers in the USCT assumed command with

knowledge of their duties, which unquestionably facilitated the

development of those units.

|

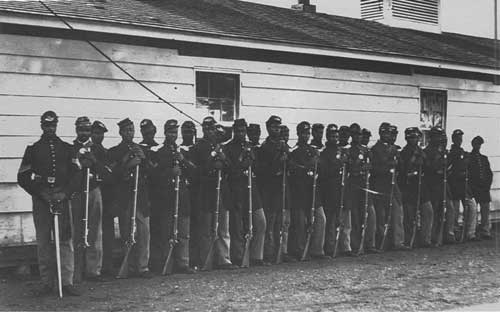

MEMBERS OF COMPANY E OF THE 4TH U.S.

COLORED TROOPS AT FT. LINCOLN. (LC)

|

Some viewed service in the USCT as an extension of their prewar

antislavery activities; others joined because they wanted to uplift the

black race. Some coveted commissions in the USCT exclusively for the

increase in pay and rank. They had no real interest in leading black

soldiers in battle. Many of its officers, after fighting a couple of

years in white units, entered the USCT because they felt this was the

best way they could contribute to the Union war effort. As veterans,

they could teach others what they had learned during active service.

More important than any motive or quality, though, was the fact that

nine of every ten of them had at least some combat experience. They had

"seen the elephant" and knew how to prepare recruits for the hazards

and chaos of a battlefield.

|

|