|

RECRUITMENT OF BLACK SOLDIERS

Like its officer selection, the means of obtaining enlisted men

differed markedly from that of white commands. Racial prejudice and the

institution of slavery created a host of problems, which forced whites

to alter their methods of recruiting black soldiers. The more simple

process for white units consisted of a call to arms, local enlistment

quotas, the hiring of substitutes, and the threat and stigma of

conscription. Those steps were merely a piece of the recruitment puzzle

for the USCT.

In the North, nearly all black people supported military service. The

Federal government had little trouble convincing men of African descent

to enlist. They viewed the war as a golden opportunity to crush the

institution of slavery, to stand on the same level and in the same

uniform as the white man, and to dispel the oppressive notions of

prejudice that haunted the black population.

|

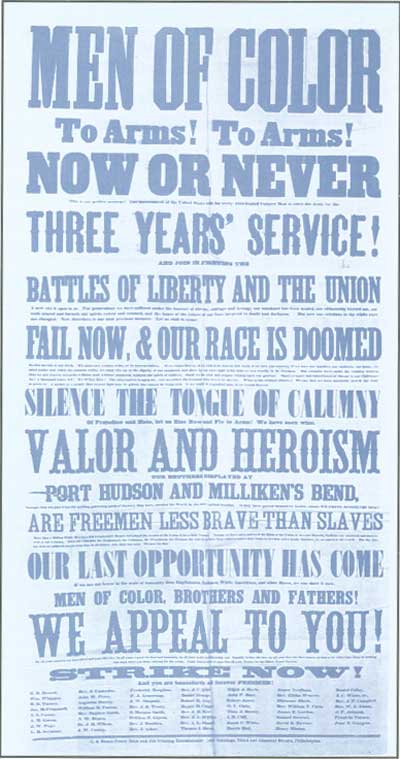

A RECRUITING POSTER URGING MEN OF COLOR TO ENLIST. (LIBRARY COMPANY OF

PHILADELPHIA)

|

The major problem of black recruitment in the Union was the hostile

white population. Arguments of a white man's war and beliefs in black

inferiority pervaded Northern white society. Neither white soldiers nor

white citizens wanted black soldiers fighting alongside them. But the

realities of war compelled reconsideration. Those whites in uniform

realized that they needed more men in arms. They preferred whites, but

black soldiers were better than nothing. At least black troops could

perform the drudgery of combat support—digging ditches, building

fortifications, driving wagons, and laboring as stevedores—to free

white men for combat.

Civilians in selected businesses, too, realized that as whites

shuffled off to war, the North lost valuable workers. Many civic leaders

joined hands with military officials to alter public perceptions of

black military service. They did so, strangely enough, by tapping into

those tightly held racist attitudes. Advertisements for the creation of

new black units not only urged them to enlist, they sometimes explained

why it was in the interest of whites to tolerate and even encourage

black volunteering. Each black man who joined the army kept one white

man from going to war. Black enlistment reduced local manpower quotas

and in numerous instances prevented a draft. It kept skilled white

workers at home, many of whom produced food and materials that aided the

war effort. Thus, in a peculiar way, black recruitment posters drew on

racial prejudice to convince whites to elevate blacks by supporting an

expansion of the USCT. And over time, this novel approach worked.

|

BLACK FAMILIES FLEEING THEIR SOUTHERN HOMES. (LC)

|

Despite the strong commitment of Northern blacks to military service,

their small population base could sustain comparatively few regiments.

The overwhelming number of black soldiers in the Union army, probably

more than 80 percent, came from the seceding states, where almost nine

of every ten black people in prewar America resided. There the

institution of slavery and a hostile white population made black

enlistment both complicated and hazardous.

Slaves who fled to Union lines frequently incurred enormous risks.

For many, flight was a huge gamble. Seldom did they know the exact

location of the Union army, and if they fell into the hands of

Confederate soldiers or citizens, the consequences were grave. Beatings,

whippings, mutilations, and even murder awaited captured runaways. To

avoid detection, they usually traveled by night and hid during the

daylight hours, obtaining food from fellow slaves or foraging as best

they could. Successful fugitives often entered Federal lines utterly

exhausted and famished. With the offer of three meals a day, clothing,

shelter, and pay, enlistment in the army was their only means of

support.

|

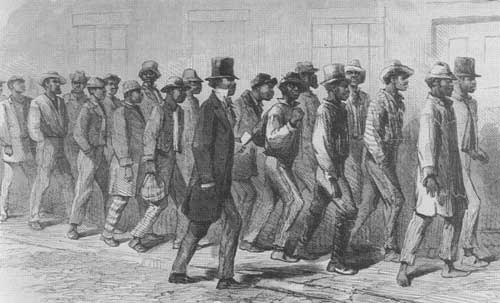

BLACK RECRUITS MARCHING IN THE STREETS OF NEW YORK CITY. (FW)

|

Runaways provided recruits in dribbles. A much better means of

gathering enlistees was through campaigning. As Federals penetrated a

region, throngs of slaves fell into Yankee hands or followed the army

back to safety. Within those occupied regions or among the hundreds,

sometimes thousands of bondsmen who used the army as their shield to

freedom, the military could obtain enough males to fill several

regiments. These campaigns offered the added benefit of securing family

members of prospective enlistees. It was no small comfort for a black

soldier to know that while he fought for the destruction of slavery and

reunion, his family was safely ensconced behind Yankee lines.

Eager recruiters greeted freedmen as they entered Federal camps. In

most cases, the individual who supervised the enlistment process would

also serve as the recruit's commanding officer. This checked the worst

abuses. Occasionally an officer would fail to explain clearly how long

the enlistment hitch was or not discuss fully the duties of soldiering

to unsuspecting former slaves. But because this officer would command

that fellow, and perhaps even enter battle with him, it behooved the

officer to treat the black man responsibly. Such was not the case with

some civilian and military recruiters. They either had quotas to meet or

got paid for each man they enlisted and had no particular interest in

the man once he took the oath of service. Many unscrupulous civilian and

military recruiters defrauded them of enlistment bounties lied to them,

and accepted men for service with obvious illnesses, injuries, wounds,

or deformities. These practices infuriated white authorities and left a

bad impression on black enlistees. It took considerable effort on the

part of their officers to break down this animosity toward any white

official.

|

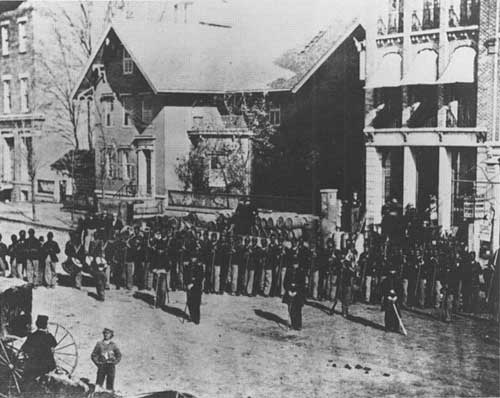

RECENT RECRUITS TO THE 5TH U.S. COLORED INFANTRY GATHER IN OHIO. (OHIO

HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

But for black soldiers in general, the initial days of military

service were thrilling moments. For the first time in their lives, they

felt as if they were on the same level as whites. They had stepped

forward in their country's time of need, and the nation accepted them

readily. They would wear the same uniforms, carry the same weapons,

endure the same hardships, and share the same joys as white soldiers.

"Put a United States uniform on his back," noticed one of their

officers, "and the chattel is a man." It uplifted them as

never before. "This was the biggest thing that ever happened in my

life," recalled a former slave. "I felt like a man with a uniform on and

a gun in my hand."

|

|