|

CONFEDERATE EFFORTS AT BLACK ENLISTMENT

Throughout the first three years of the war, several Southerners had

suggested that the Confederacy enlist black men. The Confederate

government viewed such proposals as extremist and flatly rejected

them.

Late in the war, as Confederate ranks

dwindled, voices calling for the enlistment of African Americans grew

louder and louder.

|

Late in the war, as Confederate ranks dwindled, voices calling for

the enlistment of African Americans grew louder and louder. Despite

slavery's centrality to secession, these whites realized that the

Confederacy must use its resources optimally, and one of those resources

was slavery. By early 1864, Major General Patrick Cleburne, an

outstanding division commander, circulated a proposal among some general

officers in the Army of Tennessee endorsing black enlistment. They

argued that slavery was no longer a strength but "in a military point of

view, one of our chief sources of weakness." European nations hesitated

to aid the Confederacy in its struggle for independence because of the

institution of slavery. Early in the war, slaves had produced foodstuffs

for the Confederate armies; now bondsmen ran off to labor for the Union

or serve in its armed forces. Meanwhile, Confederate armies barely held

their own against overwhelming Federal forces, primarily because these

able-bodied black males were forbidden from serving in the ranks.

At the time the proposal generated little support. The army commander

forwarded the document to Jefferson Davis, and he quashed it. Burt one

year later, with the war effort on verge of collapse, Confederate

politicians resurrected the issue of black military service. The

argument was heated. "Use all the negroes your can get, for all the

purposes for which your need them, but don't arm them," urged Georgian

Howell Cobb to the secretary of war late in the war. "The day you make

soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If

slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong."

Others pleaded for legislation that would draw black men into the fight

on the Confederate side as a practical matter. The armies desperately

needed troops, and they could fill that void. These politicians valued

an independent Confederacy more than slavery; anyway, unless the

Confederate army filled its ranks, the Union forces would crush the

secession movement and with it the institution of slavery. Back and

forth the debate raged. The decisive opinion, though, was Robert E.

Lee's. The general endorsed black enlistment. Without the infusion of

manpower the Confederate armies could not last much longer. The Union

had employed black troops with some success, Lee noted, and he believed

they would make "efficient soldiers" for the Confederacy.

|

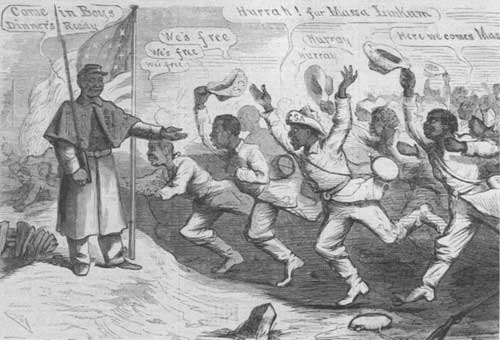

AN ILLUSTRATION MOCKING THE IDEA OF THE CONFEDERACY ATTEMPTING TO FORM

BLACK REGIMENTS. (FW)

|

When the war ended, the Confederacy was organizing its first black

units in Richmond. They never saw combat. Yet the importance of the

decision indicates how strongly the war and the performance of black

soldiers in the Union army had affected Confederate attitudes.

|

|