|

CONTRABAND OF WAR

While whites on both sides tried to keep the issues of slavery and

race in the background, black people refused to cooperate. Instead of

remaining passive, they assumed an active role in their own welfare and

compelled the Union and Confederate governments to respond to their

conduct. Thus, through their own behavior they forced the issues of

slavery and race to the forefront in the war.

The process began on a peaceful night in May 1861 in coastal

Virginia. Three slaves, whom their masters had hired out to the

Confederate government, slipped out of camp, commandeered a canoe, and

paddled their way to the safety of Union Fort Monroe. The following

morning, the Confederates noticed that the bondsmen and a canoe were

missing and correctly assumed they had headed for Yankee lines. Under a

flag of truce, a Confederate officer sailed to Fort Monroe to retrieve

the runaways. The Federals received him, and in a short while he stood

before the post commander, Brigadier General Benjamin Butler. A bald man

with dark eyes and a dark mustache, Butler had earned a reputation as a

shrewd politician and a crafty courtroom lawyer before the war.

When the Rebel officer sought a return of the chattels based on the

U.S. Fugitive Slave Law, Butler cleverly pointed out that since the

state of Virginia had seceded from the Union, its citizens could not

benefit from federal laws. Furthermore, argued Butler, since the Rebels

had employed the slaves on a Confederate military fortifications

project, they were subject to confiscation as contraband of war,

according to international law. He refused to surrender the bondsmen.

Then, in a decision made with little thought but one fraught with

repercussions, he offered to pay the three ex-slaves to build a bakery

for the Union troops there.

In one bold swoop. Butler had not only hired bondsmen to work for the

Union army, he had also established a policy that, in effect, freed

slaves. The general then dutifully notified the secretary of war of his

actions with his justifications, and the War Department endorsed them.

Several months later. Congress declared its agreement with Butler's

decisions when it codified the practice through the passage of the First

Confiscation Act. The law authorized Federal officials to seize

Confederate property, including slaves, that was used in aid of the

rebellion.

Yet Butler's decision had ramifications well beyond the First

Confiscation Act. Certainly he had forced the government to formulate a

policy on "contrabands." But at the same time he raised some serious

questions that inevitably broadened the ruling of the secretary of war

and expanded the intent of Congress. Some male slaves who had labored on

Confederate military projects had also fled to his lines with women and

children. "What shall be done with them?," he wondered. "What is their

state and condition?"

By empowering military authorities to confiscate slaves who worked

for the Confederate army, the Federal government also had obliged

military commanders to deal with a host of unusual and difficult cases

of runaway slaves. Should they return family members of legitimate

"contraband of war"? What constituted aiding the rebellion? If a slave

grew foodstuffs that the master sold to the Confederate government,

should the officer in charge confiscate the slave? In instances when a

slave labored for an avowed secessionist but did not work specifically

on military projects, should they seize the bondsman? What should

officers do if they knew the owner planned to hire the slave to the

Confederate military or had done so previously but was not doing so at

the present time? Each time that officers on the scene resolved those

matters on humanitarian grounds, they widened the breach that Congress

had created in the First Confiscation Act. They also took the nation one

step closer to complete emancipation.

|

THESE UNION MEN DISPLAY THEIR ARMY UNIFORM'S. (LC)

|

And by permitting Butler to hire black men for military projects, the

War Department paved the way for their employment in a variety of

military duties. From the construction of a bakery, to the erection of

fortifications, to work as teamsters and stevedores, black men filled

combat support positions that soldiers normally handled, which in turn

freed more troops to perform their primary function, subduing the

Rebels.

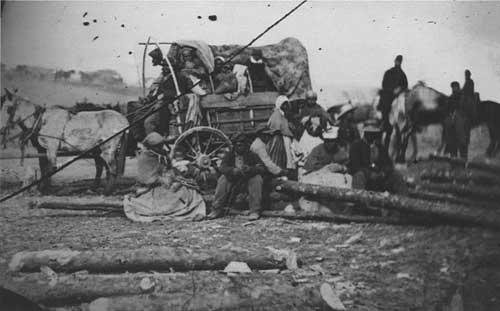

As the Union army penetrated deeper into Virginia, Tennessee,

Louisiana, Mississippi, and elsewhere, new problems developed. Huge

numbers of black refugees fled to Union lines. Some sought protection

from the ravages of war; most, however, hoped that this was the "War for

Freedom," as one bondswoman described it. They arrived in wagons, on

horseback, and on foot, individually and in clusters. Many came merely

with the tattered clothing on their backs. Only the most fortunate were

able to salvage their personal possessions.

Beatings, whippings, mutilation, and

sometimes murder awaited the unlucky runaways who were caught.

|

For slaves, flight to the Federals was a risky proposition. Beatings,

whippings, mutilation, and sometimes murder awaited the unlucky runaways

who were caught. At times, entire families escaped to Union lines.

Often, though, the risks were so high that bondsmen had to leave loved

ones behind in order to reach Federal forces. Nonetheless, on they came.

By the war's end, estimates of between 500,000 and 700,000 chattels

escaped to the Yankees.

The mass exodus overwhelmed army officers. At first, most Federal

troops returned all runaways who were not employed on Confederate

military projects to their masters. The official object of the war was

to save the Union, not to destroy slavery, and high-ranking officers

obeyed the letter of the First Confiscation Act. But for many

Northerners in and out of uniform, the situation was not that simple.

Some soldiers abhorred the notion of sending anyone back into slavery,

while others perceived the job of retrieving runaway slaves as nuisance

work. They could better use their time waging war. By early 1862, the

War Department deemed the practice so distasteful that it prohibited the

use of Federal troops in the retrieval of runaway slaves.

|

THOUSANDS OF FORMER SLAVES FOLLOWED THE UNION ARMY TO FREEDOM. (LC)

|

This mass migration had an immense effect on the Confederate economy.

Conservative estimates of the loss just in slaves surpassed one-half

billion prewar dollars. Moreover, these slaves composed between 15 and

20 percent of the black labor force in the Confederacy. Perhaps as many

as 1,000,000 white man entered the Confederate army. They sapped society

of vast quantities of food, clothing, shoes, weapons, animals,

transportation, and ammunition, while replenishing nothing. On a

drastically reduced labor force, the Confederate States had to furnish

enough to feed the same number of mouths as before the war, plus all the

material that the war demanded, much of which the Southern states had

not produced before the war and could import only sparingly through the

Federal blockade. White women filled a portion of the labor shortage,

but whites had to rely on slave labor to maintain and in some cases

increase output. Instead, hundreds of thousands of bondsmen ran off to

the Union army. The Confederacy suffered from all sorts of shortages,

which sparked a skyrocketing inflation that undermined morale at home

and in the field. Runaway slaves abandoned crops and livestock and left

railroads and homes in disrepair, mines and factory machines unworked,

and a war effort diminished.

|

A HARPER'S WEEKLY ILLUSTRATION OF BLACK CIVILIANS BEING DRIVEN

SOUTH BY CONFEDERATE OFFICERS. (LC)

|

In addition, runaway slaves caused Southern whites considerable

emotional distress. For years, Southern society had justified the

enslavement of men and women of African descent with the "positive good"

thesis. Slavery, they argued, was a natural condition for them. It

removed them from savagery and offered an opportunity to develop to

their fullest abilities. In slavery, so whites argued, blacks found

comfort and contentment. As hundreds of thousands of bondsmen abandoned

their homes in search of freedom, whites were shocked. The notion that

bands of slaves combed the country-side in search of Union lines

instilled the citizenry with terror. Whites were losing control of their

world.

Even slaves who remained at home contributed to the unrest and

anguish. In the absence of white males, the dominant force weakened.

Slaves reacted to this power vacuum with greater assertiveness. They

broke tools and equipment, slowed down their work, and grew

uncooperative and insolent, all as a means of exerting their own

strength and influence. Such behavior horrified whites in and out of the

Rebel army, who now feared servile insurrections more than ever.

|

FORMER SLAVES WERE GRANTED FREEDOM UPON ENTERING FEDERAL LINES WITH

PASSAGE OF THE SECOND CONFISCATION ACT. THIS PHOTO IS OF A FREEDMEN'S

VILLAGE IN ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA. (LC)

|

By acting on their own behalf, slaves also challenged Federal

authorities to reexamine their approach to the war. The unanticipated

response of bondsmen compelled Northern officials to adapt their

policies to meet the demands of war. First, they authorized the seizure

of slaves employed in Confederate military projects, and later the

Northern government prohibited military personnel from retrieving

runaway bondsmen. By July 1862, Congress passed legislation that went

one step farther. The mass migration of slaves to Union lines, the

significant contributions that bondsmen were making to the Confederate

war effort, and the sluggish advances of the various Federal armies

convinced Congress that the Northern government needed to prosecute the

war more boldly. The Second Confiscation Act bestowed freedom to all

slaves of Rebel masters upon entering Federal lines.

|

A BLACK SAILOR IN THE UNITED STATES NAVY. (USAMHI)

|

The Second Confiscation Act struck a blow at the heart of the

Confederate economic system by attempting to strip away valuable

laborers and offering freedom as an inducement to run away. "So long as

the rebels retain and employ their slaves in producing grains &c.,

they can employ all the whites in the field" Union Commanding General

Henry W. Halleck instructed Major General Ulysses S. Grant. "Every slave

withdrawn from the enemy is equivalent to a [Confederate] white man put

hors de combat [out of action]."

|

|