|

BLACK OFFICERS

When Butler brought the Louisiana Native Guards into Federal service

in August 1862, he appointed white and black officers alike, "precisely

as I found intelligence." All told, he doled out commissions to some

seventy-five black men as captains and lieutenants and one as a major.

In Kansas, Jim Lane, who believed he needed no authorization to recruit

a black regiment, also saw no need to seek approval for appointing a

highly qualified black as captain. The prospects for black officers

seemed promising.

|

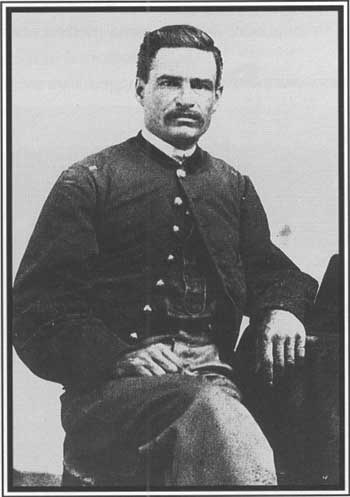

FIRST SERGEANT STEPHEN SWAILS OF THE 54TH MASSACHUSETTS FIRST BLACK

SOLDIER TO BE COMMISSIONED AN OFFICER IN A MASSACHUSETTS REGIMENT. (LC)

|

Just as swiftly, the door on black officership slammed shut. The War

Department refused Lane's regiment and particularly his black captain.

In early 1863, Governor Andrew sought permission to appoint a few

patently qualified African Americans as officers in the 54th

Massachusetts. The War Department rejected the suggestion. And when the

War Department replaced Butler as commander of the Department of the

Gulf with Banks, he immediately undertook efforts to rid himself of the

black officers in the Native Guards. Banks insisted that a black officer

"demoralizes both the white troops and the negroes." He challenged their

competency, and when that failed, Banks humiliated them at every

opportunity, until pride no longer permitted them to endure such abuse

and they resigned.

In truth, the issue had little to do with qualifications and

everything to do with racial prejudice. Whites did not like to serve

alongside black privates, let alone black officers. Whites attempted to

justify their opposition to black officership by claiming that men of

African descent lacked leadership ability, or there were not enough

satisfactorily educated black men in the entire country to fill the

officers' slots in a single regiment. In certain instances, whites

tolerated black chaplains and surgeons for black regiments, but they

would go no farther.

|

SECOND LIEUTENANT WILLIAM H. DUPREE OF THE 55TH MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY

REGIMENT. (USAMHI)

|

Throughout their service black soldiers complained bitterly over the

lack of opportunities for advancement into the officers' ranks.

Certainly black officers had served well at Port Hudson. "All that we

ask," pleaded a black sergeant, "is to give us a chance, and a position

higher than an orderly sergeant, the same as white soldiers, and then

you will see that we lack nothing." Frederick Douglass's son Lewis, a

sergeant major and combat veteran, insisted that there was plenty of

officer material in the USCT: "In regard to the capability of colored

men to perform the duties of commissioned officers, we would

respectfully suggest that there are hundreds of non-commissioned

officers in the colored regiments who are amply qualified for these

positions, both by education and experience." Black soldiers were not

asking for any special favors. "Let the Board at Washington be opened

for the examination of colored men," a black soldier suggested, "and I

have no fear for the result."

In the late stages of the war a number of black soldiers did receive

commissions as officers, primarily through the tireless efforts of

Governor Andrew. Six enlisted men in the 54th and 55th Massachusetts

gained lieutenancies in those regiments, and this breakthrough paved the

way for five more men to acquire commissions, three of them in an

artillery battery.

|

BLACK TROOPS WERE OFTEN ASSIGNED TO FATIGUE DUTY. THESE SOLDIERS ARE ON

BURIAL DETAIL. (LC)

|

All told, perhaps 110 African Americans had made it into the

officers' ranks. Other than those 75 men who secured commissions under

the auspices of Butler, most were chaplains or surgeons. Those gains at

the tail end of the war were a hollow victory because so many more

blacks who genuinely merited promotions never received serious

consideration for them.

|

|