|

PRISONERS OF WAR

Late in 1862, Confederate president Jefferson Davis attempted to

strike a fatal blow to the prospects of Union recruitment of African

Americans. He ordered government forces to turn over any captured black

troops to state authorities. The white officers would be tried according

to state law for inciting servile insurrection; the runaways would

return to slavery or suffer the death penalty, like their white

officers. No proviso covered the capture of free blacks in Union

uniform. As reinforcement, in late April and early May, the Confederate

Congress passed a joint resolution, also calling for the death of white

officers for inciting servile insurrection and the reenslavement of

black soldiers.

Although this position may have comforted Southern whites, from a

practical standpoint it was unworkable. Europeans, whom the Davis

administration was courting for military assistance, found the policy

offensive. And international law, as the Lincoln administration quickly

pointed out, supported the position that these were legitimate soldiers

and must receive the same rights as white prisoners of war. Lincoln

vowed to retaliate man for man for executed Yankees, and for each black

soldier the Confederacy returned to slavery, he would place a Rebel

soldier at hard labor. Since there were more Confederate than Federal

prisoners of war, Lincoln could ultimately outlast Davis.

In the end, the Davis administration backed down, but Confederate

officers on the scene sometimes established their own policy. Either

they refused to take black soldiers as prisoners or fought under the

black flag, which indicated that they would take no prisoners, nor would

they expect the Yankees to take any.

|

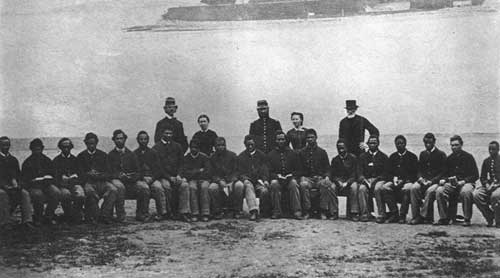

THESE BLACK SOLDIERS IN SOUTH CAROLINA WERE TAUGHT TO READ AND WRITE.

(LC)

|

As a result, wartime atrocities against the USCT were commonplace, as

Confederates hoped to discourage black enlistment and sought revenge for

their contributions to the Union army. The first killings were isolated

incidents. But as the war dragged on and Confederates became more and

more frustrated, atrocities in battle escalated. In 1864, at Poison

Springs. Arkansas, the Federals abandoned the field, leaving behind

wounded soldiers, many of them from a black regiment. Eyewitnesses

assured a Union colonel that Confederate troops murdered them on the

spot. During the Battle of Saltville, Confederates executed numerous

black troops who fell into their hands. Over the next two days, two

separate parties of Confederate troops entered Rebel hospitals and

executed seven wounded black soldiers in their beds.

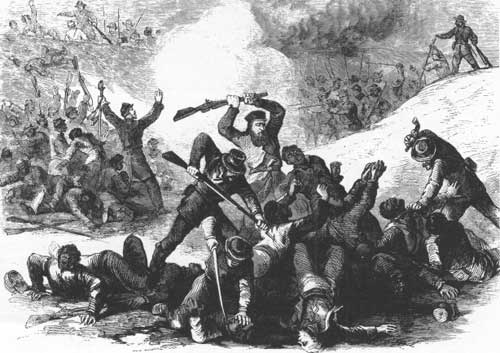

Without doubt, the most infamous series of atrocities in the war

occurred approximately forty miles north of Memphis, at Fort Pillow. The

Federal garrison consisted of 550 soldiers, nearly one-half of whom were

black. In April 1864, 1,500 Confederate cavalrymen under the command of

Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest demanded the surrender of the fort.

When the Union commander refused, Forrest's troops stormed the fort and

killed, wounded, or captured almost the entire garrison. Two-thirds of

all black soldiers at Fort Pillow were killed, compared to 36 percent of

the white Yankees.

|

BLACK SOLDIERS WERE CLUBBED AND STABBED BY CONFEDERATES AT FORT PILLOW.

(LC)

|

After the battle, Federals accused Forrest and his troops of

committing all sorts of atrocities against black soldiers. Forrest and

Confederate authorities insisted that no such brutal acts had occurred,

that only black soldiers who continued to fight or tried to escape lost

their lives. The U.S. Congress's Committee on the Conduct of the War

launched an investigation and concluded that Forrest's men had butchered

black troops. Southerners, and Forrest in particular, continued to claim

that his command had done nothing wrong. But testimony from both Federal

and Confederate troops and civilians on the scene indicates that

Forrest's men did execute some black soldiers.

Atrocities only served to solidify the USCT's reputation in the Union

army and unite the white officers and black soldiers within those units.

Black regiments responded by fighting under the black flag on occasion

or executing Confederate prisoners without warning. Black soldiers

cried, "Remember Fort Pillow" as they entered battle, and in numerous

instances they gained revenge. In the assault on Fort Blakely, where

black units charged without orders, their behavior differed little from

that of Forrest's men. According to a lieutenant in the USCT, when the

black troops charged, "the rebs were panic-struck. Numbers of them

jumped into the river and were drowned attempting to cross, or were shot

while swimming. Still others threw down their arms and run for their

lives over to the white troops on our left, to give themselves up, to

save being butchered by our niggers the niggers did not take a prisoner,

they killed all they took to a man." White officers sometimes overlooked

such retribution, while other times they proved incapable of putting a

halt to it. In fact, the problem of black soldiers executing

Confederates became so widespread that black Chaplain Henry M. Turner

complained publicly about these acts of brutality.

|

A "WAR OF EXTERMINATION"

On April 18, 1864, approximately 3,600 Confederate cavalry overran a

forage train guarded by 1,170 Union troops at an obscure spot in

southern Arkansas called Poison Springs. The 1st Kansas Colored

Volunteer Infantry, the largest unit in the Union escort, bore the brunt

of the Rebel assault and suffered heavily. Out of 438 officers and men

engaged, the regiment lost 117 slain and 65 wounded. Several Federal

survivors claimed they saw their victorious foes killing black

prisoners, including men too badly injured to get away, which accounted

for the fact that the 1st Kansas had nearly twice as many personnel

killed as wounded—an unusual occurrence in Civil War combat.

Confederate participants confirmed these atrocity stories. "The havoc

among the negroes had been tremendous," a Texas officer confided to his

journal. "Over a small portion of the field we saw at least 40 dead

bodies. . ., some scalped & nearly all stripped. . . . No black

prisoners were taken." The editor of the Washington Telegraph,

the mouthpiece of Confederate Arkansas, justified such merciless

behavior in these terms: "We cannot treat negroes . . . as prisoners of

war without a destruction of the social system for which we contend. . .

. We must claim the full control of all negroes who may fall into our

hands, to punish with death, or any other penalty."

|

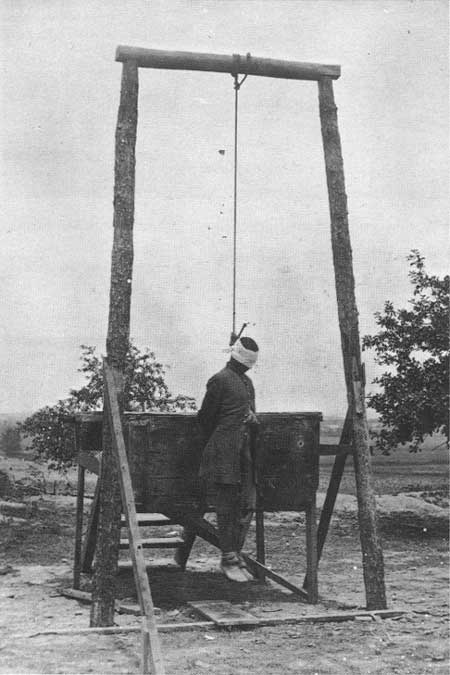

NOT ALL HARSH PUNISHMENT WAS HANDED OUT BY THE ENEMY. EIGHTY PERCENT OF

ALL UNION SOLDIERS EXECUTED FOR MUTINY WERE AFRICAN AMERICAN. (USAMHI)

|

News of the Poison Spring Massacre soon reached Major General

Frederick Steele's 13,000-man Union army at Camden, twelve miles to the

east. Colonel Samuel J. Crawford and the officers of the 2nd Kansas

Colored Infantry grimly vowed "that in future the regiment would take no

prisoners so long as the Rebels continued to murder our men."

The 2nd Kansas Colored redeemed that pledge on April 30, 1864, when

Steele's retreating forces turned on pursuing Confederates at Jenkins'

Ferry on the south side of the Saline River. At one point in the battle,

Crawford's black soldiers charged two enemy cannon, thrusting their

bayonets into surrendering gunners while shouting: "Poison Springs!" A

private in the white 29th Iowa Infantry, whose regiment supported the

2nd Kansas, wrote his family: "One of our boys seen a little negro

pounding a wounded reb in the head with the but of his gun and asked him

what he was doing. the negro replied he is not dead yet!" During a

subsequent lull in the fighting, details from the 2nd Kansas ranged the

field, cutting the throats of Confederate wounded. "We found that many

of our wounded had been mutilated in many ways," reported the surgeon of

the 33rd Arkansas Infantry. "Some with ears cut off, throats cut, knife

stabs, etc. My brother . . . had his throat cut through the windpipe and

lived several days."

Reflecting on the racially motivated killings at Poison Springs and

Jenkins' Ferry, an officer in the 40th Iowa Infantry concluded sadly:

"The 'rebs' appear to be determined to show no quarter to Black troops

or officers commanding them. It would not surprise me in the least if

this war would ultimately be one of extermination. Its tendencies are in

that direction now."

—Gregory J. W. Urwin

|

|

|