|

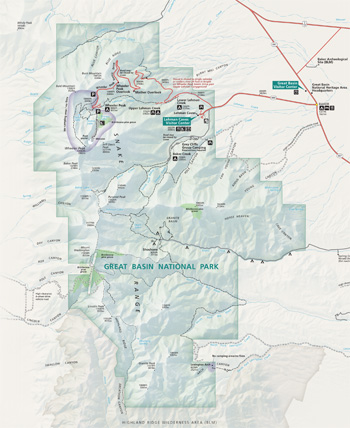

Great Basin National Park Nevada |

|

NPS photo | |

Mountains in a Sea of Sagebrush

We call it the Great Basin, this vast region of sagebrush-covered valleys and narrow mountain ranges named for its lack of drainage. Its streams and rivers mostly find no outlet to the sea, and water collects in shallow salt lakes, marshes, and mud flats to evaporate in dry desert air. It's not just one but many basins, separated by mountain ranges roughly parallel, north to south, basin and range alternating in seemingly endless geographic rhythm. Broad basins hang between craggy ranges—from California's Sierra Nevada to Utah's Wasatch Mountains.

At first glance (or after long driving) you might see the landscape as monotonous—a sea of pale green shrubs. But looks deceive. As with oceans, much life here is not immediately apparent. Above the sagebrush sea, mountain ranges form a high-elevation archipelago as islands of cooler air and more abundant water. Richly varied plants and animals live up there that could not survive in the lower desert.

Congress created Great Basin National Park in 1986, including much of the South Snake Range, a superb example of a desert mountain island. From sagebrush at its base to Wheeler Peak's 13,063-foot summit, the park offers streams, lakes, abundant wildlife, varied forest types (even groves of ancient bristlecone pines), alpine plants, and many limestone caverns, including beautiful Lehman Caves.

The Great Basin

Centered on Nevada the Great Basin stretches from California's Sierra

Nevada to Utah's Wasatch Mountains. The region features high, silent

valleys, many mountain ranges, and few rivers. Great Basin National Park

protects the South Snake Range near Utah's border east of Ely, Nev.

On the Edge of the Desert

The Snake Range exemplifies how living things and landscapes interrelate. As elevation increases, the climate changes, creating habitats for different plants and animals. The most recent ice age glaciers sprawled across these high peaks. The air was cooler, so forests of bristlecone and limber pine grew in the valley, beside long sinuous lakes. Lake Bonneville was the largest—today's Great Salt Lake is its shrunken remnant—and 15,000 years ago its waves lapped shoreline 10 miles from today's park boundary.

All that changed starting about 10,000 years ago as the climate warmed. Glaciers melted. Lakes dried up. Desert plants invaded the desiccated valleys. The Snake Range became an island surrounded by desert, its elevation giving temperate-climate dwellers cooler refuge. For many organisms with no means of transport, desert basins are rigid barriers, and isolated species develop unique adaptations as surely as those on ocean islands.

A Land of Lakes and Forests

Close beneath Wheeler Peak's summit the ice age persisted until recently as a small, one-of-its-kind Great Basin glacier. This token called to mind Snake Range—capping glaciers a few millennia back. Other evidence is easy to find. Piles of glacial debris—boulders, sand, gravel—form mounds and ridges, and sparkling Teresa and Stella lakes sit in ice-gouged hollows.

These were alpine glaciers, not the continental ice sheets that blanketed the northern part of our continent. Ice never reached the valley floor here, but melted at about 8,000 feet of elevation. Baker Creek drainage's shape shows this. Above 8,000 feet glaciers plucked and carried bedrock, making mountain slopes wider and U-shaped. Below that level, cascading streams cut sharp-sided, V-shaped canyons.

Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive offers good views of the range. Starting near the park entrance, it climbs from Lehman Creek across a dry shoulder of mountain, ending near the treeline. In 12 miles it gains 3,400 feet in elevation, showing you varied habitats. You go from pinyon-juniper woodlands along an aspen-lined creek bed, through shrubby mountain mahogany and manzanita, into deep forests of Englemann spruce and Douglas fir. Then you move on to flower-spangled meadows and subalpine forest—limber pine, spruce, and aspen—at Wheeler Peak campground.

Hiking opportunities abound throughout the park. Easy to moderate trails lead to subalpine lakes and a bristlecone pine forest. More strenuous is a climb up Wheeler Peak, the park's highest point. Rangers lead nature walks and tours of world-class Lehman Caves.

Treeline and Above

In the South Snake Range, 13 peaks rise above 11,000 feet, where the winter is never far off. Snow can fall in any month, even July. Freezing night temperatures are common. Plants cope with a short growing season, poor soil, thin air, high winds, and intense solar radiation. High winds punish anything much above the ground—even hikers. Living up there demands a low profile. Lichens cling like paint to rocks and dwarfed plants grow snug to the ground, anchored in crevices. Shrubs look like a bonsai gardener pruned them, and trees live in cavities or hollows.

The trees highest up in the Snake Range, the limber and bristlecone pines, appear between 9,500 and 11,000 feet. Both are hardy, but bristlecone pines are masters of longevity, enduring not centuries but millennia. On rocky slopes past Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive's end, you walk among trees 2,000 to 3,000 and more years old.

Not all bristlecones live that long. Ironically, the oldest grow near treeline where survival is the most difficult. Adversity seems to foster long life. They grow slowly, a branch at a time, their needles living up to 40 years. Often, a tree looks nearly dead—a thin strip of living tissue clinging to a gnarled, naked trunk. Most species decay under such conditions, but bristlecone wood's high resin content prevents rot. Instead, the wood erodes, like stone, from wind and ice crystals. Even dead wood endures and is of scientific value. At lower elevations' lesser extremes, bristlecones grow faster and larger but die at tender ages, 300 or 400 years.

People of the Great Basin Archeology reveals that prehistoric peoples lived along the ancient Lake Bonneville around 10,000 years ago. From about 1100 to 1300, American Indians (known as Fremont) lived in small villages near today's Baker and Garrison. They irrigated corn, beans, and squash in the valley and hunted in the mountains. Several rock art sites in the park recall their presence. Small kin groups of Shoshone and Paiute peoples lived near the springs and other water sources from 1300 until recently. They hunted and gathered wild foods, but their staple, especially in winter, was pinyon nuts. Their descendants still live in this area and share the harvest with resident pinyon jays, rock squirrels, wood rats, and other small animals.

The Underground World

Lehman Caves is a single cavern despite the name. It extends a quarter-mile into the limestone and marble that flank the base of the Snake Range. American Indians knew of it long before the rancher and miner Absalom Lehman explored it in 1885. It is one of the region's most profusely decorated caves.

What you see today started hundreds of thousands of years ago. Surface water, turned slightly acidic from carbon dioxide gas, mixed with water deep below the surface, dissolving the soluble rock at the horizontal water table. Evidence of the dissolving action from the slowly circulating water was recorded in the cave's rock as spherical domes in ceilings and spoon-shaped scallops on walls. Eventually the water drained from the cave, leaving behind hollow rooms and sculptured walls.

In the second stage of cavern development, water percolated down from the surface, carrying small amounts of dissolved limestone (calcite). Drop by drop, over centuries, seemingly insignificant trickles deposited the wonders of stone. The result is a rich display of cave formations scientists call speleothems. Lehman Caves has familiar formations like stalactites, stalagmites, columns, draperies, flowstone, and soda straws. But there are also rarities, like shields—two roughly circular plates fastened like flattened clam shells, often with graceful stalactites and draperies hanging from their lower plate. Lehman Caves is most famous for its abundant shields.

Location and Services

Great Basin Visitor Center, on NV 487 in Baker, is open in summer only; contact the park for hours. Lehman Caves Visitor Center, six miles west of Baker, is open year round 8 am to 4:30 pm (longer in summer). Driving distance (miles) to Lehman Caves Visitor Center: Las Vegas 286; Salt Lake City 234; Reno 385; and Cedar City 142.

Both visitor centers have information, bookstores, and exhibits. Lehman Caves and Lehman Caves Visitor Center are closed Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. Great Basin Visitor Center is open in summer.

Entry to the park is free. Fees are charged for campgrounds, cave tours, and RV sanitary station (summer only). A cafe and gift shop next to Lehman Caves Visitor Center are open in summer.

Baker has restaurants, hotels, gas, and basic food supplies. Garrison has no facilities. Nearest cities are Ely, NV, 68 miles west, and Delta, UT, 106 miles east. Unpaved and unmaintained roads on the park's west and south sides have no services.

Order publications about the park from Western National Parks Association at the park address.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. Call or check our website

Things To See and Do

(click for larger map) |

For a One-day Visit

Stop first at Great Basin Visitor Center to see the exhibits and learn

about the Great Basin Desert. Drive to Lehman Caves Visitor Center and

take a ranger-led cave tour. Drive to Wheeler Peak, then follow trails

to subalpine lakes and bristlecone pine groves.

For a Longer Visit

Climb Wheeler Peak, and explore park canyons. Snake Creek flows through

aspen groves beneath limestone outcroppings. Lexington Arch Road

requires high-clearance and four-wheel drive. Witness how plant

communities of the Great Basin recover after a fire in the north end of

the park. All park roads except Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive are unpaved

and rarely traveled. Snow closes many roads in winter. Ask for details

at a visitor center.

Activities

Scheduled tours of Lehman Caves run when the Lehman Caves Visitor Center

is open. Cave tours are up to a ½-mile walk on a paved trail with

stairways and indirect lighting; tours take up to 90 minutes. Shorter

walks are available. Dress warmly; the cave is 50°F year-round. An

adult must accompany those under 16. For advance ticket sales please

visit www.recreation.gov.

A Nevada fishing license is required; state regulations apply. Hunting is prohibited. Nevada law governs the possession of firearms. Firearms are prohibited in federal buildings. Horseback riding is allowed on some trails. Mountain bike only on designated motor vehicle roadways. Vehicles and drivers on park roads must be licensed. ATVs must be street-legal and licensed. Off-roading prohibited.

Camping

Four campgrounds have water (summer only), restrooms, fire rings,

tables, and tent pads. One campground is open year-round (no water in

winter). Primitive sites along Strawberry and Snake creeks have tent

sites, fire grates, and tables; some Snake Creek sites have pit toilets

but no water. Some sites have road access in summer only.

Backcountry

Hiking and backpacking options abound, but many park trails are

primitive and route finding may be difficult. Most routes follow

ridgelines or canyons. Plan ahead: bushwhacking through mountain

mahogany can be tough or impossible. Get information on conditions and

topographic maps at a visitor center. Backcountry registration is

strongly recommended.

Regulations

Pets must be on a leash six-feet-long or less. Pets are prohibited in

caves and buildings, on trails except Lexington Arch Trail, and over 100

feet from roads. • Campfires are allowed only in campgrounds and

picnic areas in designated grills. Campfires are prohibited above 10,000

feet; use portable stoves. • Federal law protects all natural and

cultural features; do not disturb or damage. • Do not feed

wildlife. • In Lehman Caves stay on the trail with the ranger. Do

not touch cave formations. • Obey speed limits and traffic

regulations. Visit the park website for more information, and enjoy a

safe visit.

Hiker Warnings

Many trails rise above 10,000 feet. Avoid overexertion. Be prepared for

sudden weather changes. When storms threaten or when you hike above the

treeline, take rain gear and warm clothing. Avoid exposed areas and

ridges during electrical storms.

Water Surface water might not be available in summer; carry at least one quart per person—more for day-long hikes. Visitor centers have drinking water year-round; campgrounds have water in summer. Untreated water must be purified before drinking.

Footgear Wear hiking boots or sturdy shoes with ankle support. Loose and sharp rocks are common, especially off maintained trails. Mineshafts and tunnels, part of park history, are dangerous; stay out and stay alive!

Note: The alpine world is ecologically fragile. Plants grow slowly at high elevations; their margin of survival is thin. To protect these areas, stay on roads or trails where possible.

Source: NPS Brochure (2018)

|

Establishment

Great Basin National Park — October 27, 1986 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A biological inventory of eight caves in Great Basin National Park Final Report (Jean K. Krejca and Steven J. Taylor, September 30, 2003)

A Cattle Controversy: Great Basin National Park and the Struggle for Environmental Tourism in Nevada (Peter A. Kopp, extract from Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 57 Nos. 1-2, Spring-Summer 2014; ©Nevada Historical Society)

Accessibility Self-Evaluation and Transition Plan, Great Basin National Park (March 2017)

Alternatives Workbook: Background and Alternatives, Great Basin National Park (July 1988)

Alternatives Workbook Response: General Management Plan, Great Basin National Park (February 1989)

Amphibian Inventory: Great Basin National Park Final Report 2002/2003 (Bryan Hamilton, December 18, 2003)

An Ecological Landscape Analysis, Great Basin National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GRBA/NRR-2019/2002 (Robert S. Unnasch, Patrick J. Comer and David P. Braun, September 2019)

An Archeological Overview of Great Basin National Park Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology No. 49 (Krista Deal, 1988)

Archeological Survey and Site Assessment at Great Basin National Park Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology No. 53 (Susan J. Wells, 1990)

Baseline Water Quality Inventory of Great Basin National Park NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR-2009/201 (Margaret A. Horner, Gretchen M. Baker and Debra L. Hughson, May 2009)

Basin and Range: A History of Great Basin National Park, Nevada, Historic Resource Study (Harlan D. Unrau, 1990)

Bat Blitz in Brief for Great Basin National Park Project Brief (Joseph Danielson and Kelsey Ekholm, May 23, 2021)

Bonneville Cutthroat Trout Restoration Project, Great Basin National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/NRR-2008/055 (Gretchen Baker, Neal Darby, Tod Williams and John Wullschleger, September 2008)

Bristlecone pine tree rings and volcanic eruptions over the last 5000 yr (Matthew W. Salzer and Malcom K. Hughes, extract from Quaternary Research, Vol. 67, 2007)

Cave Temperature and Management Implications in Lehman Caves, Great Basin National Park, USA (Stanka Šebela, Gretchen Baker and Barbara Luke, extract from Geoheritage, Vol. 11, 2019)

Characterization of Surface-Water Resources in the Great Basin National Park Area and Their Susceptibility to Ground-Water Withdrawals in Adjacent Valleys, White Pine County, Nevada USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2006-5099 (Peggy E. Elliott, David A. Beck and David E. Prudic, 2006)

Chemical characteristics of surface waters of Great Basin National Park (Ruth W. Jacobs, Peter O. Nelson and Gary L. Larson, December 1993)

Climate Change and the Great Basin (Jeanne C. Chambers, extract from USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RMRS-GRT-204, 2008)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Baker Ranger Station, Great Basin National Park (2023)

Dedication of Lehman Caves National Monument: Ascent and Perilous Descent of Mount Wheeler, August 1922 (Cada C. Boak, extract from Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XVI No. 2, Summer 1973; ©Nevada Historical Society)

Effects of Flow Diversion on Snake Creek and its Riparian Cottonwood Forest, Great Basin National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GRBA/NRR-2020/2104 (Derek M. Schook, David J. Cooper, Jonathan M. Friedman, Steven E. Rice, Jamie D. Hoover and Richard D. Thaxton, April 2020)

Evaluating Connection of Aquifers to Springs and Streams, Eastern Part of Great Basin National Park and Vicinity, Nevada USGS Professional Paper 1819 (David E. Prudic, Donald S. Sweetkind, Tracie R. Jackson, K. Elaine Dotson, Russell W. Plume, Christine E. Hatch and Keith J. Halford, 2015)

Field Guide to Cave Life (Gretchen M. Baker, 2007)

Final General Management Plan/Development Concept Plans/Environmental Impact Statement, Great Basin National Park, Nevada (September 1992)

Foundation Document, Great Basin National Park, Nevada (August 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Great Basin National Park, Nevada (January 2015)

Geochemical Investigation of Source Water toCave Springs, Great Basin National Park,White Pine County, Nevada USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5073 (David E. Prudic and Patrick A. Glancy, 2009)

Geologic Map of Great Basin National Park, Nevada (2014)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Great Basin National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2014/762 (J.P. Graham, February 2014)

Geophysical Characterization of Range-Front Faults, Snake Valley, Nevada USGS Open-File Report 2010-1016 (Theodore H. Asch and Donald S. Sweetkind, 2010)

Great Basin bristlecone pine mortality: Causal factors and management implications (Barbara J. Bentz,, Constance I. Millar, James C. Vandygriff and Earl M. Hansen, extract from Forest and Ecology Management, Vol. 509, 2022)

Great Basin National Park Aspen Stand Condition and Health Assessment NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GRBA/NRR-2014/782 (Margaret A. Horner, Bryan T. Hamilton and Louis Provencher, March 2014)

Great Basin National Park, Final General Management Plan, Development Concept Plans, Environmental Impact Statement (December 1992)

Historic American Buildings Survey

Rhodes Cabin HABS-NEV-17-1 (Melvin M. Rotsch, August 1966)

Integrated Monitoring of Hydrogeomorphic, Vegetative, and Edaphic Conditions in Riparian Ecosystems of Great Basin National Park, Nevada USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5185 (Erik A. Beever and D.A. Pyke, 2004)

Johnson Lake Mine Historic District Stabilization Environmental Assessment Draft (September 2014)

Junior Ranger, Great Basin National Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Book, Great Basin National Park (2021; for reference purposes only)

Lampenflora in a Show Cave in the Great Basin Is Distinct from Communities on Naturally Lit Rock Surfaces in Nearby Wild Caves (Jake Burgoyne, Robin Crepeau, Jacob Jensen, Hayden Smith, Gretchen Baker and Steven D. Leavitt, extract from Microorganism, Vol. 9, 2021)

Lehman Caves (Otto T.W. Nielson, extract from Zion-Bryce Nature Notes, Vol. 6 No. 4, July-August 1934)

Lehman Caves...Its Human History: From the Beginning Through 1965 (Keith A. Trexler, 1966, revised 1978)

Lehman Caves Management Plan, Great Basin National Park, Baker, Nevada Draft (May 2019)

Lehman Caves Management Plan, Great Basin National Park, Baker, Nevada (June 2019)

Lehman Caves Management Plan Environmental Assessment, Great Basin National Park, Baker, Nevada Draft (July 2019)

Lehman Orchard Management Plan, Great Basin National Park (January 1990)

Mammals of Great Basin National Park Final Report (Eric A. Rickart and Shannen L. Robson, January 2005)

Marmot Distribution and Habitat Association in the Great Basin (Chris H. Floyd, extract from Western North American Naturalist, Vol. 64 No. 4, 2004)

Monitoring Temporal Change in Riparian Vegetation of Great Basin National Park (Erik A. Beever, David A. Pyke, Jeanne C. Chambers, Fred Landau and Stanley D. Smith, ©Western North American Naturalist, Vol. 65 No. 3, 2005)

Mountain Temperature Changes From Embedded Sensors Spanning 2000 m in Great Basin National Park, 2006-2018 (Emily N. Sambuco, Bryan G. Mark, Nathan Patrick, James Q. DeGrand, David F. Porinchu, Scott A. Reinemann, Gretchen M. Baker and Jason E. Box, extract from Frontiers in Earth Science, Vol. 8 Article 292, July 2020)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Baker Ranger Station (Harlan D. Unrau, May 15, 1992)

Jonson Lake Mine Historic District (Susan J. Wells, July 19, 1995)

Lehman Orchard and Aqueduct (#22) (F. Ross Holland, Jr., December 1971)

Osceola (East) Ditch (Harlan D. Unrau, April 3, 1989)

Rhodes Cabin (#19) (F. Ross Holland, Jr., December 1971)

Wheeler Peak Campground (Tina Bishop, Shelby Scharen, Earen Hummel, Elizabeth Hallas and Susan Hacker, January 5, 2018)

Native Americans, the Lehman Caves, and Great Basin National Park (Steven Crum, extract from Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 48 No. 3, Fall 2005; ©Nevada Historical Society)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Great Basin National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GRBA/NRR-2016/1105 (Patrick J. Comer, Marion S. Reid, Jon P. Hak, Keith A. Schulz, David P. Braun, Robert S. Unnasch, Gretchen Baker, Ben Roberts and Judith Rocchio, October 2015)

Park Newspaper (The Bristlecone): 1987 • 1990 • 2000 • 2006 • 2007 • 2009 • 2010 • 2010 • 2011 • 2012 • 2014 • 2015 • 2016 • 2017 • 2019

Poster — Counting Cave Shields: A Lehman Caves Study (Morgan Hill and Gretchen M. Baker, 2021)

Preliminary Geochemical Assessment of Water from Selected Streams, Springs, and Caves in the Upper Baker and Snake Creek Drainages in Great Basin National Park, Nevada, 2009 USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2014-5108 (Angela P. Paul, Carl E. Thodal, Gretchen M. Baker, Michael S. Lico and David E. Prudic, 2014)

Public Involvement Issues: Great Basin National Park, Nevada (November 1987)

Quantifying Wildlife Use of Cave Entrances Using Remote Camera Traps (Gretchen M. Baker, extract from Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, Vol. 77 No. 3, December 2015)

Response to memorandum by Rowley and Dixon regarding U.S. Geological Survey report titled "Characterization of Surface-Water Resources in the Great Basin National Park Area and Their Susceptibility to Ground-Water Withdrawals in Adjacent Valleys, White Pine County, Nevada" USGS Open-File Report 2006-1342 (David E. Prudic, 2006)

Results of Field Investigations for Proposed National Park in the Snake Range of Eastern Nevada (1959)

Riverscape Interpretation in Great Basin National Park: A Geomorphic Assessment of Streams and Riparian Areas NPS Science Report NPS/SRA-2025/237 (Scott M. Shahverdian and Derek M. Schook, February 2025)

Seismic Velocities and Thicknesses of Alluvial Deposits along Baker Creek in the Great Basin National Park, East-Central Nevada USGS Open-File Report 2009-1174 (Kip K. Allander and David L. Berger, 2009)

Scoping report: Great Basin National Park water resources management plan NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-91/05 (September 1991)

Soil Survey of Great Basin National Park, Nevada (2009)

Study of Alternatives: Great Basin — Spring Valley / Snake Range Study Area (February 1981)

The Midden (Resource Management Newsletter)

The Oasis (Mojave Desert Network)

Vegetation Inventory Project: Great Basin National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MOJN/NRR-2012/568 (Dan Cogan, Jeanne E. Taylor and Keith Schulz, September 2012)

Vegetation Classification Report: Great Basin National Park (Keith A. Schulz and Mark Hall, March 2011)

Whose Land Is It? The Battle for the Great Basin National Park, 1957-1967 (Gary E. Elliot, extract from Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 34 No. 1, Spring 1991; ©Nevada Historical Society)

Wild Caves and Karst Management Plan, Great Basin National Park Draft (May 2019)

Wild Caves and Karst Management Plan, Great Basin National Park (June 2019)

Wild Caves and Karst Management Plan Environmental Assessment, Great Basin National Park Draft (July 2019)

Year in Review 2018: Great Basin National Park (2018)

Year in Review 2019: Great Basin National Park (2019)

Year in Review 2020: Great Basin National Park (2020)

Great Basin National Park (Duration: 4:41, November 28, 2012)

Great Basin National Park Film (Duration: 24:08, March 20, 2021)

Lehman Caves Virtual Tour (Part 1: Entrance Tunnel to Lodge Room) (Duration: 10:06, July 30, 2020)

Lehman Caves Virtual Tour (Part 2: Queen's Bath to Grand Palace) (Duration: 9:23, July 30, 2020)

Lehman Caves Virtual Tour (Part 3: Lodge Room to Exit Tunnel) (Duration: 7:30, July 30, 2020)

grba/index.htm

Last Updated: 25-Feb-2025